Kathleen Howard ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blockade Runners: MS091

Elwin M. Eldridge Collection: Notebooks: Blockade Runners: MS091 Vessel Name Vessel Type Date Built A A. Bee Steamship A.B. Seger Steamship A.C. Gunnison Tug 1856 A.D. Vance Steamship 1862 A.H. Schultz Steamship 1850 A.J. Whitmore Towboat 1858 Abigail Steamship 1865 Ada Wilson Steamship 1865 Adela Steamship 1862 Adelaide Steamship Admiral Steamship Admiral Dupont Steamship 1847 Admiral Thatcher Steamship 1863 Agnes E. Fry Steamship 1864 Agnes Louise Steamship 1864 Agnes Mary Steamship 1864 Ailsa Ajax Steamship 1862 Alabama Steamship 1859 Albemarle Steamship Albion Steamship Alexander Oldham Steamship 1860 Alexandra Steamship Alfred Steamship 1864 Alfred Robb Steamship Alhambra Steamship 1865 Alice Steamship 1856 Alice Riggs Steamship 1862 Alice Vivian Steamship 1858 Alida Steamship 1956 Alliance Steamship 1857 Alonzo Steamship 1860 Alpha Steamship Amazon Steamship 1856 Amelia Steamship America Steamship Amy Steamship 1864 Anglia Steamship 1847 Anglo Norman Steamship Anglo Saxon Steamship Ann Steamship 1857 Anna (Flora) Steamship Anna J. Lyman Steamship 1862 Anne Steamship Annie Steamship 1864 Annie Childs Steamship 1860 Antona Steamship 1859 Antonica Steamship 1851 Arabian Steamship 1851 Arcadia Steamship Ariel Steamship Aries Steamship 1862 Arizona Steamship 1858 Armstrong Steamship 1864 Arrow Steamship 1863 Asia Steamship Atalanta Steamship Atlanta Steamship 1864 Atlantic Steamship Austin Steamship 1859 B Badger Steamship 1864 Bahama Steamship 1861 Baltic Steamship Banshee Steamship 1862 Barnett Steamship Barroso Steamship 1852 Bat Steamship -

Holocaust Fiction with a Twist: Christians Imagining Jews in the Shoah a Paper Presented at the Association of Jewish Libraries

1 Holocaust Fiction with a Twist: Christians Imagining Jews in the Shoah A Paper Presented at the Association of Jewish Libraries Annual Convention, Pasadena, CA June 19, 2012 Mark Stover California State University, Northridge Abstract Over the past 25 years, evangelical Christian authors have written dozens of popular novels across a spectrum of genres that have one theme in common: Jewish characters interacting with Christians during and after the Holocaust. In this paper, I will describe and analyze the works of multiple Christian authors who have written fictional narratives that imagine Jewish characters in a variety of situations related to the Shoah. Many of these books contain what are often referred to as "conversion narratives." I will critique these narratives and will address such questions as intended audience, the legitimacy of writing from an outsider's perspective, and the controversial nature of writing about religious conversion. Introduction I begin this paper by quoting from Yaakov Ariel, who has written a great deal about the nature of evangelical Christian attitudes toward Jews: "One must conclude that the evangelical attitudes toward the Jewish people and their activities on the Jews' behalf derive first and foremost from their evangelical messianic hope, which in its turn represents an entire worldview, conservative and reactive in nature. The evangelicals' pro- Israel attitude and their keen concern for the physical well-being of Jews derive from their beliefs about the function of the Jews in the advancement of history toward the arrival of the Lord. ... Evangelical Christians cannot, therefore, be described as philosemites. Their support of Jewish causes represent an attempt to promote their own agenda and their opinions on Jews have not always been flattering. -

The Newark Post

-...--., -- - ~ - -~. I The Newark Post PLANS DINNER PROGRAM oC ANDIDATES Newark Pitcher Twirls iFINED $200 ON ANGLERS' ASS'N No Hit, No-Run Game KIWANIS HOLDS FORP LACE ON Roland Jackson of t he Newark SECOND OFFENCE SEEKS INCREASE J uni or Hig h Schoo l baseball ANNUAL NIGHT team, ea rly in life realized t he SCHOOLBOARD I crowning ambition of every Drunken Driver Gets Heavy Newark Fishermen Will Take AT UNIVERSITY ',L baseball pitcher, when, Friday, Penalty On Second Convic- 50 New Members; Sunset S. GaJlaher Fil es For Re- I he pi tched a no-hit, no-run game against Hockessin, in the D. I. 300 Wilmington Club Mem election , !\ ll's. F. A. Wheel tion; Other T rafflc Cases Lake .Well Stocked A. A. Elementary League. To bers Have Banquet In Old ess Oppno's Him ; Election make it a real achievement, the ga me was as hard and cl ose a s Frank Eastburn was a rre ted, Mon The Newa rk Angler Association College; A. C . Wilkinson May 4. ewark Pupils Win a ba ll game can be that comes to day, by a New Cast le County Con held its first meeting of the year, last a decision in nine innings, for stabl e on a charge of dr iving while F riday night at the Farmer's Trust Arranges Program Newark won the game with a in toxicated. After hi s arrest he was Company. O. W. Widdoes, the presi lone run in the lucky seventh. taken before a physician and pro dent, presided. -

THE SIGNIFICANCE of ALLEGORICAL CHRISTIAN to REPRESENT BUNYAN's LIFE in the PILGRIM's PROGRESS a Thesis Presented to The

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ALLEGORICAL CHRISTIAN TO REPRESENT BUNYAN’S LIFE IN THE PILGRIM’S PROGRESS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Program in English Language Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Magister Humaniora (M.Hum) in English Language Studies by Baja Tigor Hasudungan Pasaribu 06. 6332. 014 SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY 2010 Dedicated to My dear mother, Hartini and brother, Oka, v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would acknowledge my supervisor Dr. B.B. Dwijadmoko, M.A. for his supervision. Thank you, Pak Dwi for being so patient, encouraging and supportive. I also thank Mike for his help with my study/thesis. I am grateful for the trust that God has given me to undertake a Masters degree under His financial support. I particularly want to thank mum and bro for the prayers, supports, and encouragements. You have been the best parent and brother God has given me. 8 February 2010 Baja Tigor Hasudungan Pasaribu vi ABSTRACT Baja Tigor Hasudungan Pasaribu. (2009). THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ALLEGORICAL CHRISTIAN TO REPRESENT BUNYAN’S LIFE IN THE PILGRIM’S PROGRESS, Yogyakarta: English Language Studies. Graduate Program. Sanata Dharma University. This thesis talks about The Pilgrim’s Progress, one of the most widely read books in English literature. It is a fiction-prose allegory relating the journey and adventures of Christian, a man who flees the City of Destruction and sets out for the Celestial City. Bunyan uses The Pilgrim’s Progress as a narrative strategy to express his own attitude toward his society and government in his life time. Bunyan personified his own life experiences and faith through the main character of the text (Christian), and bad characters in the text personified all the figure who had suppressed or persecuted him in real life. -

Christian Universalism in the Novels of Denise Giardina William Jolliff George Fox University, [email protected]

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of English Department of English 2016 The ideW Reach of Salvation: Christian Universalism in the Novels of Denise Giardina William Jolliff George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eng_fac Recommended Citation Jolliff, William, "The ideW Reach of Salvation: Christian Universalism in the Novels of Denise Giardina" (2016). Faculty Publications - Department of English. 28. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eng_fac/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of English by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wide Reach of Salvation: Christian Universalism in the Novels of Denise Giardina William Jolliff It would be careless and reductive to refer to Denise Giardina as a regionalist; she is simply someone paying attention to her life. - W. Dale Brown Maybe Denise Giardina has written too well about Appalachia. Storming Heaven (1987) and The Unquiet Earth (1992), the two novels set in the West Virginia coalfields of the author's childhood, have received serious critical attention: but with few exceptions, her other novels have been ignored by academic commentators. Had Giardina written with such perfect and articulate craft about Dublin or London or New York, critics might be slower to think of her simply as a regionalist or even a writer of place. And I suspect she would have less trouble being heard when she says, as she has many times, "As much as I'm an Appalachian writer, I get called a political writer, but the label that is most appropriate for my writing is theological writing" (Douglass 34). -

Dr. J. T. SALTER Rose & Ellsworth

B u c h a n a n R ecord, BIG BARGAINS . PUBLISHED EVERY THURSDAY, ----- EVT----- -iN - 7 0 H 1 T Gr- H O L M E S. TSRMS, S 1.50 PER YEAR eAXABCE IS ADVANCE. uiEencuiEs nits Kim si imam. VOLUME XXV. BUCHANAN, BEBPJEN COUNTY, MICHIGAN, THURSDAY. OCTOBER 29, 1891. NUMBER 40. OFFICE—IaRecorfl BuUding,OakStreet THE PESSIMISTIC MILLIONAIRE. that the quiet and silence seemed not Selfishness W ell Bewavded. Ask No Questions. unnatural. BT BROWNE I'liHIiOIAJs. The subject of the ethics of polite The old proverb to the effect that Business Directory. She opened the door and'went in. ness as manifested by travelers in those who ask no questions will be In Iho days when I was a growing boy, Ho one was there. The door into the yielding or retaining their car seats told no lies conveys a lesson that is I longed for man’s pow er and pleasure save, ticket office was open, hut the seat in SABBATU SERVICES. forms a never-ending topic of conver worth heeding. Even among the well- But now that I’ve reached that high estate, front of the desk was empty. sation among those who have occasion bred, questions are often asked which SERVICES are Reid, every Sabbath at 10:30 Long1 Goats & Cloaks. I ’d ju st like to bo a b oy onco m ore. Phyllis looked around in some per O o’ clock A. a ., at the Church o f the “ Larger to study the various phases of the it is irksome or inexpedient, to answer. -

Dwight D. Eisenhower Stereo Slide Collection

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER STEREO SLIDE COLLECTION Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum Audiovisual Collection Because of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s interest in stereographic photography, the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum holds a large collection of stereo slides. The majority of the 1,154 slides were taken during the years 1948-1958 by Eisenhower and members of his staff using a Realist Stereo Camera made by the David White Company, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The collection documents events from his personal life as well as major news events. Slides relate to the personal interests, family, and social life of Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower as well as friends and acquaintances. There are slides of friends, members of their staff and business associates, either appearing alone or as a group with the Eisenhower’s. Other slides taken during official SHAPE trips include scenic views as well as official functions, and military inspections. There are slides of places and scenes, primarily scenic in nature, including views of Camp David, Maryland; Abilene, Kansas; and the Augusta National Golf Course. Slides taken of historic events include coverage of the 1952 Presidential Campaign, the 1953 Inauguration, as well as international events such as the 1953 Bermuda Conference and the funeral of King George VI in 1952. 1 STEREO SLIDES 71-856-1--23 Lipson, Portugal, January 1959 (23) 71-857-1--7 Luxemburg, January 19, 1951, Pearl Mesta’s Residence (3) Luxemburg, January 19, 1951, Hotel Alfa (4) 71-858-1 Pad Hambourg, Germany, January -

Copyright Chawton House Library

THE VILLAGE COQUETTE; A NOVEL, IN THREE VOLUMES. BY THE AUTHOR OF “SUCH IS THE WORLD.” VOL. I. Women, like princes, find no real friends: All who approach them their own ends pursne: Lovers and ministers are never true. Hence oft from reason heedless beauty strays, And the most trusted guide the most betrays: Hence by fond dreams of fancy’d pow’r amus’d, When most you tyrannize, you’re most abus’d.—LITTLETON. LONDON: PRINTED FOR G. AND W. B. WHITTAKER, AVE-MARIA-LANE. MDCCCXXII. LONDON: Printed by WILLIAM CLOWES, Northumberland-court. PREFACE. IT is an observation which, though vulgar, is nevertheless true, “That one half of the world does not know how the other half lives;” and I am not certain that my VILLAGE COQUETTE throws any additional light on this common saying, but I believe all who shall honour her with a perusal, will discover the moral I would inculcate, though I must leave its application to the judgment of the reader. If I have not given a new reading of the remark to which I have alluded, I have offered some illustrations that may recall to the reader’s mind the portraitures of beings whose multiplicity renders them familiar and insignificant in the crowded scenes of life, but who, when shewn up in their native simplicity, can “Hold the mirror up to nature,” and in their wayward fancy, tell an unadorned tale of as much value to their listening auditors, as the famed romance of heroes who have fleshed their falchions with the blood of their enemies. -

51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA

Northeast Modern Language Association 51ST ANNUAL CONVENTION March 5–8, 2020 Boston, MA Local Host: Boston University Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo SUNY 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS President Carole Salmon | University of Massachusetts Lowell First Vice President Brandi So | Department of Online Learning, Touro College and University System Second Vice President Bernadette Wegenstein | Johns Hopkins University Past President Simona Wright | The College of New Jersey American and Anglophone Studies Director Benjamin Railton | Fitchburg State University British and Anglophone Studies Director Elaine Savory | The New School Comparative Literature Director Katherine Sugg | Central Connecticut State University Creative Writing, Publishing, and Editing Director Abby Bardi | Prince George’s Community College Cultural Studies and Media Studies Director Maria Matz | University of Massachusetts Lowell French and Francophone Studies Director Olivier Le Blond | University of North Georgia German Studies Director Alexander Pichugin | Rutgers, State University of New Jersey Italian Studies Director Emanuela Pecchioli | University at Buffalo, SUNY Pedagogy and Professionalism Director Maria Plochocki | City University of New York Spanish and Portuguese Studies Director Victoria L. Ketz | La Salle University CAITY Caucus President and Representative Francisco Delgado | Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY Diversity Caucus Representative Susmita Roye | Delaware State University Graduate Student Caucus Representative Christian Ylagan | University -

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds As of 4/30/2021

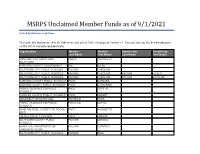

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds as of 9/1/2021 Sorted by Member Last Name To search this document, click the Edit menu and select Find, or just press Control + F. You can also use the Bookmarks pane on the left to navigate alphabetically. Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND PABLA TARUNJEET BALTIMORE HARFORD COUNTY GOVERNMENT PAC ELLEN BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA PACANA ELISEO BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA PACANA ELIZALDE HARFORD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE BARBARA HOWARD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE CATHERINE PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PACE CRYSTAL SCHOOLS CHARLES COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE ROBERT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND PACHECO ELVIA PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PACHECO MAYRA SCHOOLS ANNE ARUNDEL CO DEPT OF SOCIAL PACK ANJENETTE SERV TALBOT COUNTY COUNCIL PACK LANARD BALTIMORE COUNTY PUBLIC PACKER AMANDA SCHOOLS MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF PACKER KIMBERLY TRANSPORTATION BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PADDER IRAM Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADDOCK JACK SCHOOLS PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADDOCK JACK PADDOCK LANDON SCHOOLS ANNE ARUNDEL CO PUBLIC SCHOOLS PADDY GLADYS PADDY CYNTHIA WESTERN MARYLAND HOSPITAL PADEN GLENNA PADEN HAROLD CENTER PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADEN JENNIFER SCHOOLS WASHINGTON COUNTY PUBLIC PADEN JULIAN PADEN MARY SCHOOLS TOWN OF CHEVERLY PADGETT MATTHEW HARFORD COUNTY GOVERNMENT PADGETT TIFFANY -

Ungit's Character, Role, and Meaninig in C. S. Lewis's Christian Framework of Till We Have Faces

Ungit's Character, Role, and Meaninig in C. S. Lewis's Christian Framework of Till We Have Faces Crnogorac, Petar Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:756179 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-25 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Diplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti; smjer: nastavnički (dvopredmetni) Petar Crnogorac Ungit's Character, Role, and Meaning in C. S. Lewis's Christian Framework of Till We Have Faces Diplomski rad Zadar, 2016. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Diplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti; smjer: nastavnički (dvopredmetni) Ungit's Character, Role, and Meaning in C. S. Lewis's Christian Framework of Till We Have Faces Diplomski rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Petar Crnogorac Doc. dr. sc. Marko Lukić Zadar, 2016. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Petar Crnogorac, ovime izjavljujem da je moj diplomski rad pod naslovom Ungit's Character, Role, and Meaning in C.S. Lewis's Christian Framework of Till We Have Faces rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. -

The Evolution of Yeats's Dance Imagery

THE EVOLUTION OF YEATS’S DANCE IMAGERY: THE BODY, GENDER, AND NATIONALISM Deng-Huei Lee, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2003 APPROVED: David Holdeman, Major Professor Peter Shillingsburg, Committee Member Scott Simpkins, Committee Member Brenda Sims, Chair of Graduate Studies in English James Tanner, Chair of the Department of English C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Lee, Deng-Huei, The Evolution of Yeats’s Dance Imagery: The Body, Gender, and Nationalism. Doctor of Philosophy (British Literature), August 2003, 168 pp., 6 illustrations, 147 titles. Tracing the development of his dance imagery, this dissertation argues that Yeats’s collaborations with various early modern dancers influenced his conceptions of the body, gender, and Irish nationalism. The critical tendency to read Yeats’s dance emblems in light of symbolist- decadent portrayals of Salome has led to exaggerated charges of misogyny, and to neglect of these emblems’ relationship to the poet’s nationalism. Drawing on body criticism, dance theory, and postcolonialism, this project rereads the politics that underpin Yeats’s idea of the dance, calling attention to its evolution and to the heterogeneity of its manifestations in both written texts and dramatic performances. While the dancer of Yeats’s texts follow the dictates of male-authored scripts, those in actual performances of his works acquired more agency by shaping choreography. In addition to working directly with Michio Ito and Ninette de Valois, Yeats indirectly collaborated with such trailblazers of early modern dance as Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Maud Allan, and Ruth St.