Chapter 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ruby 1960) • Uses a Solid Matrix Or Crystal Carrier • Eg Glass Or Sapphire

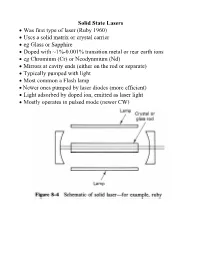

Solid State Lasers • Was first type of laser (Ruby 1960) • Uses a solid matrix or crystal carrier • eg Glass or Sapphire • Doped with ~1%-0.001% transition metal or rear earth ions • eg Chromium (Cr) or Neodynmium (Nd) • Mirrors at cavity ends (either on the rod or separate) • Typically pumped with light • Most common a Flash lamp • Newer ones pumped by laser diodes (more efficient) • Light adsorbed by doped ion, emitted as laser light • Mostly operates in pulsed mode (newer CW) Flash Lamp Pumping • Use low pressure flash tubes (like electronic flash) • Xenon or Krypton gas at a few torr (mm of mercury pressure) • Electrodes at each end of tube • Charge a capacitor bank: 50 - 2000 µF, 1-4 kV • High Voltage pulse applied to tube • Ionizes part of gas • Makes tube conductive • Capacitor discharges through tube • Few millisec. pulse • Inductor slows down discharge Light Source Geometry • Earlier spiral lamp: inefficient but easy • Now use reflectors to even out light distribution • For CW operation use steady light sources Tungsten Halogen or Mercury Vapour • Use air or water cooling on flash lamps Q Switch Pulsing • Most solid states use Q switching to increase pulse power • Block a cavity with controllable absorber or switch • Acts like an optical switch • During initial pumping flash pulse switch off • Recall the Quality Factor of resonance circuits (eg RLC) 2π energy stored Q = energy lost per light pass • During initial pulse Q low • Allows population inversion to increase without lasing • No stimulated emission • Then turn switch on -

A History of High-Power Laser Research and Development in the United Kingdom

High Power Laser Science and Engineering, (2021), Vol. 9, e18, 86 pages. doi:10.1017/hpl.2021.5 REVIEW A history of high-power laser research and development in the United Kingdom Colin N. Danson1,2,3, Malcolm White4,5,6, John R. M. Barr7, Thomas Bett8, Peter Blyth9,10,11,12, David Bowley13, Ceri Brenner14, Robert J. Collins15, Neal Croxford16, A. E. Bucker Dangor17, Laurence Devereux18, Peter E. Dyer19, Anthony Dymoke-Bradshaw20, Christopher B. Edwards1,14, Paul Ewart21, Allister I. Ferguson22, John M. Girkin23, Denis R. Hall24, David C. Hanna25, Wayne Harris26, David I. Hillier1, Christopher J. Hooker14, Simon M. Hooker21, Nicholas Hopps1,17, Janet Hull27, David Hunt8, Dino A. Jaroszynski28, Mark Kempenaars29, Helmut Kessler30, Sir Peter L. Knight17, Steve Knight31, Adrian Knowles32, Ciaran L. S. Lewis33, Ken S. Lipton34, Abby Littlechild35, John Littlechild35, Peter Maggs36, Graeme P. A. Malcolm OBE37, Stuart P. D. Mangles17, William Martin38, Paul McKenna28, Richard O. Moore1, Clive Morrison39, Zulfikar Najmudin17, David Neely14,28, Geoff H. C. New17, Michael J. Norman8, Ted Paine31, Anthony W. Parker14, Rory R. Penman1, Geoff J. Pert40, Chris Pietraszewski41, Andrew Randewich1, Nadeem H. Rizvi42, Nigel Seddon MBE43, Zheng-Ming Sheng28,44, David Slater45, Roland A. Smith17, Christopher Spindloe14, Roy Taylor17, Gary Thomas46, John W. G. Tisch17, Justin S. Wark2,21, Colin Webb21, S. Mark Wiggins28, Dave Willford47, and Trevor Winstone14 1AWE Aldermaston, Reading, UK 2Oxford Centre for High Energy Density Science, Department of Physics, -

Few-Cycle Pulses Amplification for Attosecond Science Applications: Modeling and Experiments

FEW-CYCLE PULSES AMPLIFICATION FOR ATTOSECOND SCIENCE APPLICATIONS: MODELING AND EXPERIMENTS by MICHAËL HEMMER M.S. Engineering Ecole Nationale Supérieure de Physique de Marseille, 2005 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Optics and Photonics at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2011 Major professor: Martin Richardson © 2011 Michaël Hemmer ii ABSTRACT The emergence of mode-locked oscillators providing pulses with durations as short as a few electric-field cycles in the near infra-red has paved the way toward electric-field sensitive physics experiments. In addition, the control of the relative phase between the carrier and the pulse envelope, developed in the early 2000’s and rewarded by a Nobel price in 2005, now provides unprecedented control over the pulse behaviour. The amplification of such pulses to the millijoule level has been an on-going task in a few world-class laboratories and has triggered the dawn of attoscience, the science of events happening on an attosecond timescale. This work describes the theoretical aspects, modeling and experimental implementation of HERACLES, the Laser Plasma Laboratory optical parametric chirped pulse amplifier (OPCPA) designed to deliver amplified carrier-envelope phase stabilized 8-fs pulses with energy beyond 1 mJ at repetition rates up to 10 kHz at 800 nm central wavelength. The design of the hybrid fiber/solid-state amplifier line delivering 85-ps pulses with energy up to 10 mJ at repetition rates in the multi-kHz regime tailored for pumping the optical parametric amplifier stages is presented. -

Tattoo Removal with an Electro-Optic Q-Switched Nd:YAG Laser with Unique Pulse Dispersion Michael Gold, MD

STUDY Tattoo Removal With an Electro-optic Q-Switched Nd:YAG Laser With Unique Pulse Dispersion Michael Gold, MD The objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of an electro-optic Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with standard pulse and pulse dispersion options for the treatment of unwanted tattoos. tatistics released in 2002 from the American the treatment of tattoos, the following principles apply2-4: Society of DermatologicalCOS Surgery suggested DERM (1) amateur tattoos are easier to remove than professional that 50% of individuals receiving tattoos ones; (2) distally located tattoos are harder to remove, at that time would want them removed in theoretically due to lymphatic drainage; (3) older tattoos 5 years.1 The growing demand for effective are easier to remove; (4) darker Fitzpatrick skin types Stattoo removal without scars, pigmentation issues, or have a greater risk for scarring and pigmentary changes textural changes has fueledDo the search forNot alternatives during Copy laser tattoo removal procedures. to dermabrasion, cryotherapy, surgical excision, CO2 or Three types of Q-switched lasers (694-nm Q-switched argon laser treatment, and other superficial and nonspe- ruby, 755-nm Q-switched alexandrite, and the 1064-nm cific destructive methods of the past.2 Studies with ruby Q-switched Nd:YAG) have been studied in the treatment of lasers in the 1960s were early milestones in the use of tattoos. Each wavelength has an affinity for selective absorp- light-based therapy for the clearance of tattoo ink. In tion by certain ink colors, the most common colors being the succeeding 30 years, the Q-switched ruby, Nd:YAG, black (Q-switched ruby, Q-switched Nd:YAG, Q-switched and alexandrite lasers would all prove the usefulness alexandrite), blue-black (Q-switched ruby, Q-switched of the theory of selective photothermolysis in this area. -

Infrared Upconversion for Astronomy

Infrared UpconversionUpconversion for Astronomy Robert W.W. Boyd Department of PhysicsPhysics University of California Berkeley, California 94720 Abstract The fieldfield ofof infraredinfrared upconversionUpconversion forfor astronomy astronomy is is reviewed. reviewed. The basic theory of upconversionUpconversion is presented, along with a brief historical summary of upconversionUpconversion techniques.techniques. SeveralSeveral investi-investi gators have employed upconverters in astronomical studies, but have met withwith onlyonly modestmodest success.success. UpconversionUpconversion willwill becomebecome IR a useful detection method for astronomy only if substantial butbut perhaps forseeable improvementsimprovements can be realized. Introduction A novel solutionsolution toto the problem ofof infraredinfrared detectiondetection isis affordedafforded by thethe processprocess ofof upconversion. Upconversion. TheThe upconversionUpconversion processprocess isis shown schematicallyschematically inin FigureFigure 1.1. InfraredInfrared radiationradiation of frequency Figure 2.2. ImagingImaging property ofof the the upconversion Upconversion process. process. ConservationConservation of photonphoton momentummomentum (hk)(hk) requiresrequires thatthat the the sum sum frequencyfrequency photon be emitted inin aa unique direction. rections of propagation. In fact,fact, toto aa goodgood approximation,approximation, the Nonlinear crystal angle of propagation ofof thethe sumsum frequencyfrequency radiationradiation isis relatedrelated to the angleangle -

Treatment with the Q-Switched, Nd-Yag Laser in the Wavelengths Of

Treatment with the Q-switched, Nd-Yag Laser in the wavelengths of 532nm and 1064nm for the Treatment of Post-endovenous Ablation and Post-sclerotherapy Hyperpigmentation: A Retrospective Case Series. Angela Macri DO, MS, PGY-3 Dermatology Resident at Sampson Regional Medical Center Mojgan Hosseinipour DO, PGY-1 Traditional Rotating Intern at Sampson Regional Medical Center Jaimie Nuckolls DO, PGY-1 Traditional Rotating Intern at Sampson Regional Medical Center Kamran Goudarzi MD, FACS, FICS Attending at DermOne Dermatology, Cosmetic, and Scarless Vein Center Jonathan Crane DO, FAOCD, FAAD Dermatology Program Director, Sampson Regional Medical Center **The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest Introduction Table and Figures Results Varicose veins can be very problematic to patients causing a great deal All locations showed improvement where 1 had minimal, 2 had of medical and cosmetic concern. Treatment of varicose veins by either moderate, and 6 had marked improvement while 2 had complete sclerotherapy or endovenous ablation causes obliteration of the lumen resolution. Two locations required only one treatment to get a of the vessel, fibrosis, and an inflammatory reaction that allows leakage complete resolution. Four sites obtained a marked improvement after 2 of red blood cells into the perivascular space. When red blood cells are treatments, however, one other site with marked improvement did broken down by macrophages hemosiderin is deposited in the dermis. require 3 treatments. Two locations had a moderate amount of These procedures also cause inflammation in the epidermis and improvement after 2 treatments and one site had a minimal amount of dermis, creating a reactive melanogenesis. -

Evaluation of the Free-Running Ruby Laser for Hair Removal a Retrospective Study

Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1998; 78: 48–51 Evaluation of the Free-running Ruby Laser for Hair Removal A Retrospective Study PETER BJERRING1, HUGH ZACHARIAE2, HANS LYBECKER2 and MARC CLEMENT3 1Department of Dermatology, University Hospital of Aarhus, Denmark, 2The Mølholm-Clinic, Vejle, Denmark, and 3Swansea School of Higher Education, Swansea, UK The free-running ruby laser has recently been introduced for Mode of action of the ruby laser removal of unwanted hair growth. It is assumed that the mode of action of ruby laser depilation is that of selective photothermo- Based on Monte Carlo computer simulations, the mode of lysis of the melanin-rich structures. The present data reflects action seems to be the following: red (694 nm) ruby laser light our results of ruby treatment of 133 patients attending a is transmitted through epidermis to dermis, where the light dermatological laser clinic for hair removal. When success of after only a few micrometres is scattered in all directions due the laser treatment was defined as greater than 50% hair to sudden changes of refractive indices of different anatomical removal, 59.0% of patients reported successful results after 90 structures (fibres, cells, vessels). The absorbing chromophore or more days after last treatment. With success defined as of the ruby laser wavelength is melanin. Structures such as greater than 25% hair removal at 90 days, successful treatment epidermis, hair shaft and hair bulb are primary targets, while was obtained in 75.0%. only insignificant absorption occurs in haemoglobins (3). Part Also, the patients evaluated the overall result of their treat- of the light enters the hair follicles at different levels and is ments. -

Fiber Optics

FIBER OPTICS Prof. R.K. Shevgaonkar Department of Electrical Engineering Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Lecture: 18 Optical Sources- Introduction to LASER Diodes Fiber Optics, Prof. R.K. Shevgaonkar, Dept. of Electrical Engineering, IIT Bombay Page 1 The basic principles of operation of a LASER as an optical source for high speed long-distance optical communication are based on stimulated emission in an environment of population with a positive optical feedback which endows the LASER with optical oscillatory characteristics and, thus helps the LASER to emit a highly coherent optical output. However, there are different ways that have been proposed to achieve the above configuration for a LASER and consequently, there are different types of LASERs too. The very first and most primitive type of LASERs is the Ruby Laser. It is a solid state LASER consisting of a solid ruby rod exposed to a flashing light as shown in the figure 18.1 below: Figure 18.1: A Ruby LASER arrangement The winding shown in the above figure is actually the filament of the flashing light that is used to pump the electrons from the ground state to the excited state in order to maintain the population inversion condition. To understand the working of a ruby LASER, let us look into the energy level diagram of Ruby (Figure18.2). Figure 18.2: Energy Level Diagram of Ruby Fiber Optics, Prof. R.K. Shevgaonkar, Dept. of Electrical Engineering, IIT Bombay Page 2 A flashing light pumps electrons from the ground state (E0) to the two excited states E2 and E3 and create a condition of population inversion. -

Theory and Application of Ruby Laser

International Journal of Research e-ISSN: 2348-6848 p-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 04 Issue14 November 2017 Theory and Application of Ruby Laser Nishar Ahamad , Chhail Bihari Lomod , Deepak Gaur, Suresh Kumar Meena, Girraj Prasad Prajapati Department of Physics, Students, B.Sc. First year, Parishkar College of Global Excellence, Jaipur Abstract: resonator. Laser medium or gain medium in ruby laser In this paper explain Working Process of ruby Laser, 3+ applications and Future Aspects .In a ruby laser, a single crystal of ruby (Al2O3 : Cr ) in the form of cylinder acts as a laser medium or active Keyword: Laser action, Active Medium Resonator medium. The laser medium (ruby) in the ruby laser is cavity made of the host of sapphire (Al2O3) which is doped with small amounts of chromium ions (Cr3+). The ruby has good thermal properties. Introduction A ruby laser is a solid-state laser that uses the synthetic ruby crystal as its laser medium. Ruby laser is the first successful laser developed by Maiman in 1960.Ruby laser is one of the few solid-state lasers that produce visible light. It emits deep red light of wavelength 694.3 nm. Construction of ruby laser A ruby laser consists of three important elements: laser medium, the pump source, and the optical Pump source or energy source in ruby laser The pump source is the element of a ruby laser system that provides energy to the laser medium. In a ruby laser, population inversion is required to achieve laser emission. Population inversion is the process of achieving the greater population of higher energy state than the lower energy state. -

Laser Cooling of Solids

Laser cooling of solids Galina Nemova Ecole Polytechnique de Montréal Canada 1. Introduction At the present the term “laser cooling”, which does not imply the cooling of lasers, is most often used to describe cooling and trapping of atoms and ions to extremely low temperatures right to the nanokelvin regime. There are differant methods of laser cooling of atoms amd ions, for example, Doppler cooling (Hänsch & Schawlow, 1975), where light forces are exerted by absorption and subsequent spontaneius emission of photons. The rate of these processes depends on the velocity of an atom or ion due to the Doppler shift. This method is limited in terms of the reachable temperature by Doppler limit . Sisyphus cooling (Dalibard & Cohen-Tannoudji, 1985), which involves a polarization gradient and therefore sometimes is called polarization gradient cooling, allows to get temperatutes substantially below the Doppler limit. It goes down to the much lower recoil limit associated with the recoil momentum related to the absorption or emission of a single photon. But the recoil limit can be overcamed by the method of velocity-selective coherent population trapping (Aspect et al., 1988), which allows sub-recoil temperatures in the nanokelvin regime. This area of sience has progressed immensely in the last two decades facilitating the observation of Bose-Einstin condensates and many related phenomena and resulting in physics Nobel prizrs 1997 (Chu, Cohen-Tannoudji & Philips, 1997) and 2001 (Cornell, Ketterle & Weiman, 2001). It is worth to emphasise, what may be many researchers don’t realize, that nearly half a cenury before Doppler cooling of atoms was observed, cooling of solids by anty-Stoks fluorescence was proposed by Peter Pringsheim (Pringsheim, 1929). -

RUBY LASER.Pdf

RUBY LASER Dr. ANANT KUMAR SINHA ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DEPTT. OF PHYSICS A.M. COLLEGE, GAYA OVERVIEW •Introduction •Historical importance •Construction •Working •Application •Drawbacks INTRODUCTION A ruby laser is a solid-state laser that uses a synthetic ruby crystal as its gain medium. It was the first type of laser invented, and was first operated by Theodore H. "Ted" Maiman at Hughes Research Laboratories on 1960-05-16 . The ruby mineral (corundum) is aluminum oxide with a small amount(about 0.05%) of chromium which gives it its characteristic pink or red color by absorbing green and blue light. The ruby laser is The ruby laser is used as a pulsed laser, producing red light at 694.3 nm. After receiving a pumping flash from the flash tube, the laser light emerges for as long as the excited atoms persist in the ruby rod, which is typically about a millisecond. HISTORICAL IMPORTANCE A pulsed ruby laser was used for the famous laser ranging experiment which was conducted with a corner reflector placed on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts. This determined the distance to the Moon with an accuracy of about 15 cm. a three level solid state laser. LASER CONSTRUCTION The active laser medium (laser gain/amplification medium) is a synthetic ruby rod. Ruby is an aluminum oxide crystal in which some of the aluminum atoms have been replaced with chromium atoms(0.05% by weight). Chromium gives ruby its characteristic red color and is responsible for the lasing behavior of the crystal. Chromium atoms absorb green and blue light and emit or reflect only red light. -

Unit 4 LASERS By. Dr. M. Z. Ansari

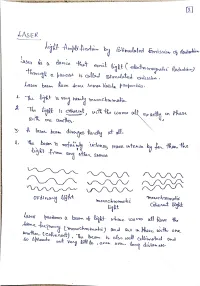

Differences between Stimulated and spontaneous emission of radiation S.no Stimulated Emission Spontaneous emission 1 An atom in the excited state is induced to The atom in the excited state returns to the return to the ground state , thereby resulting ground state thereby emitting a photon, in two photons of same frequency and without any external inducement is called energy is called Stimulated emission Spontaneous emission 2 The emitted photons move in the same The emitted photons move in all directions direction and is highly directional and are random 3 The radiation is highly intense , The radiation is less intense and is monochromatic and coherent incoherent. 4 The photons are in phase, there is a constant The photons are not in phase (i.e.) there is phase difference. no phase relationship between them The rate of transition is given by The rate of transition is given by R21 (St) = B21 u() N2 R21 (Sp) = A21 N2 Population Inversion: Population Inversion creates a situation in which the number of atoms in higher energy state is more than that in the lower energy state. Usually at thermal equilibrium, the number of atoms N2 i.e., the population of atoms at excited state is much lesser than the population of the atoms at ground state N1 that is N1 > N2. The Phenomenon of making N2 > N1 i.e, the number of particles N2 more in higher energy level than the number of particles N1 in lower energy level is known as Population Inversion or inverted population. The states of system, in which the population of higher energy state is more in compression to the population of lower energy state are called negative temperature states.