Analysis of EU-Japan Business Cooperation in Third Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 (Description Abbreviated)

(Description abbreviated) 1 First of all, please allow me to introduce myself briefly. My name is Shigeki Yamaguchi, and I am in charge of the Enterprise & Solutions Segment. After joining NTT DATA Corporation (“NTT DATA”) in 1984, I engaged in development and consulting duties before being sent on loan, following which I served, in the Third Enterprise Sector, as head of a unit responsible for distribution and services industries. Subsequently, the Company conducted an organizational realignment, transferring the payment field, composed mainly of CAFIS, from the Financial Segment to the Enterprise & Solutions Segment. I was then in charge of the IT Services & Payments Services Sector. Starting from June 2017, as officer responsible for the Enterprise & Solutions Segment, I have been in charge of the manufacturing industry and solutions fields and network and cloud services as well as China & APAC Segment. 2 The Enterprise & Solutions Segment consists of three sectors. The first one is the IT Services & Payments Services Sector, which is responsible mainly for distribution and services industries. The second one is the Manufacturing IT Innovation Sector, responsible mainly for manufacturing industry, etc. The third one is the Business Solutions Sector, which pursues operations mainly for IT networks, data centers and cloud services as well as new technologies comprising AI and the IoT. The Enterprise & Solutions Segment is involved in many group companies. 3 (Description abbreviated) 4 (Description abbreviated) 5 Let me brief you on our business outline. The Enterprise & Solutions Segment pursues operations to provide (i) high value-added IT services that support business activities such as manufacturing, distribution and service industries, (ii) credit card and other payment services in collaboration with the IT services of different segments and (iii) platform solutions. -

Notice of Convocation of the 120Th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders of Mitsubishi Estate Co., Ltd

[Translation for Reference and Convenience Purposes Only] Please note that the following is an unofficial English translation of Japanese original text of the Notice of Convocation of the 120th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders of Mitsubishi Estate Co., Ltd. The Company provides this translation for reference and convenience purposes only and without any warranty as to its accuracy or otherwise. In the event of any discrepancy between this translation and the Japanese original, the latter shall prevail. (Securities Code: 8802) June 5, 2019 Dear Shareholders Junichi Yoshida Director, President and Chief Executive Officer 1-1, Otemachi 1-chome, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo NOTICE OF CONVOCATION OF THE 120th ORDINARY GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS You are cordially invited to attend the 120th Ordinary General Meeting of Shareholders of Mitsubishi Estate Co., Ltd. (the “Company”), to be held as follows. If you are unable to attend the meeting, you may otherwise exercise your voting rights in writing (by mail) or by electromagnetic means (the Internet, etc.). Please read the attached REFERENCE DOCUMENTS FOR THE GENERAL MEETING OF SHAREHOLDERS provided below, and you are requested to exercise your voting rights by 5:45 p.m., on Wednesday, June 26, 2019. 1. Time and Date: 10 a.m., Thursday, June 27, 2019 2. Place: Royal Park Hotel, 3F, Royal Hall, 1-1, Nihonbashi-Kakigara-cho 2-chome, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 3. Objectives of the Meeting: Reports: 1. Reports on Business Report and Consolidated Financial Statements, as well as Results of the Audits of the Consolidated Financial Statements by the Accounting Auditor and Audit Committee for Fiscal 2018 (From April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2019) 2. -

OZEL EK 2019 Ingilizce 4.Pdf

"[NBTSBGM ÎPLTFÎFOFLMJ .FSDFEFT#FO[&VSP LBNZPOBJMFTJ Mercedes-#FO[&VSPBSBmMBS EÜLCBLÎNNBMJZFUJZMFDFCJOJ[JZPSNB[ EBIBV[VOCBLÎNBSBMÎLMBSÎZMBJÜUFOBMÎLPZNB[ TEKBOR “Hayat Taşır” Telefon: +90(412) 456 6052 • Mail: [email protected] • Fax: +90(412) 456 6085 Adres: Bismil Diyarbakr Yolu 8.Km Bismil/DùYARBAKIR www.tekbor.com.tr Bu bir güç gösterisi. Yeni X-Class V6. 258 BG ve 550 Nm torka sahip V6 turbo motoruyla şimdi yollarda. BaķWan Sona (WNLle\LFL: ZF’den KomponenWler ve 6LVWHmler 2WREÕV \ROFXODUĊ PDNVLPXP JÕYHQOLN YH NRQIRU EHNOHUOHU =) QLQ ķDQ]ĊPDQODUĊ YH DNVODUĊ EX EHNOHQWLOHULQ NDUķĊODQPDVĊQD\DUGĊPFĊROPDNWDGĊU µUÕQOHULPL] \ROFXODUĊQ DUDFD KĊ]OĊ YH JÕYHQOL ELU ķHNLOGH LQLS ELQPHOHULQL JÕYHQOL YH NH\LƮL ELU \ROFXOXN \DSPDODUĊQĊVDøODU=)ÕUÕQOHULELUELUOHULQHWDPRODUDNX\XPOXGXUYHHQÕVWGÕ]H\WHNQRORML\OHJHOLķWLULOGLNOHUL LÀLQGLQDPLNKĊ]ODQPDYHD\QĊ]DPDQGDVHVVL]ÀDOĊķPDÏ]HOOLNOHULQHVDKLSWLU =)NRPSRQHQWOHULLOHDUDFĊQĊ]ĊQKHPNXOODQĊPÏPUÕPDOL\HWOHULQLKHPGHDUDÀYHÀHYUHÕ]HULQGHNLROXPVX] HWNLOHULQLD]DOWDELOLUVLQL] ]IFRPEXVHs BU GURUR TABLOSUNA BU GURUR BELGESİ YERLİ MALI Yerli üretim Ford Trucks, yerli malı belgesine sahip ilk ağır ticari markası olmanın gururunu yaşıyor. Bugün de yüksek yerlilik oranıyla üretimine devam ediyor, Türkiye kazanıyor. Ford Trucks Her yükte birlikte 444 36 73 / 444 FORD www.fordtrucks.com.tr TRUCKS • ,TRSZQ2&#,3+ #0-$+','120'#1510#"3!#","2&##!-,-+7512)#,-4#0 7-,# &,"5'2&2Ҳ-$2&#,#50#1'"#,2'*%-4#0,+#,21712#+',30)#7T,2&'1!-,2#62Q 0#1307","#01#!0#20'2Q,"#','1207-$$',,!#5#0#+#0%#"',2-1',%*#+','1207TTT The Turkish economy was affected by the US- The tension experienced in Turkey-US relations China trade war, Brexit developments, the Fed’s was reflected adversely to the markets due to the case decisions to raise interest rates, geopolitical risks, and of Pastor Andrew Brunson, and the speculative attacks also by some speculative exchange rate attacks. -

Sumitomo Corporation's Dirty Energy Trade

SUMITOMO CORPORATION’S DIRTY ENERGY TRADE Biomass, Coal and Japan’s Energy Future DECEMBER 2019 SUMITOMO CORPORATION’S DIRTY ENERGY TRADE Biomass, Coal and Japan’s Energy Future CONTRIBUTORS Authors: Roger Smith, Jessie Mannisto, Ryan Cunningham of Mighty Earth Translation: EcoNetworks Co. Design: Cecily Anderson, anagramdesignstudio.com Any errors or inaccuracies remain the responsibility of Mighty Earth. 2 © Jan-Joseph Stok / Greenpeace CONTENTS 4 Introduction 7 Japan’s Embrace of Dirty Energy 7 Coal vs the Climate 11 Biomass Burning: Missing the Forest for the Trees 22 Sumitomo Corporation’s Coal Business: Unrepentant Polluter 22 Feeding Japan’s Coal Reliance 23 Building Dirty Power Plants Abroad and at Home 27 Sumitomo Corporation, climate laggard 29 Sumitomo Corporation’s Biomass Business: Trashing Forests for Fuel 29 Global Forests at Risk 34 Sumitomo and Southeastern Forests 39 Canadian Wood Pellet Production 42 Vietnam 44 Sumitomo Corporation and Japanese Biomass Power Plants 47 Sumitomo Corporation and You 47 TBC Corporation 49 National Tire Wholesale 50 Sumitomo Corporation: Needed Policy Changes 3 Wetland forest logging tied to Enviva’s biomass plant in Southampton, North Carolina. Dogwood Alliance INTRODUCTION SUMITOMO CORPORATION’S DIRTY ENERGY TRADE—AND ITS OPPORTUNITY TO CHANGE While the rest of the developed world accelerates its deployment of clean, renewable energy, Japan is running backwards. It is putting in place policies which double down on its reliance on coal, and indiscriminately subsidize biomass power technologies that accelerate climate change. Government policy is not the only driver of Japan’s dirty energy expansion – the private sector also plays a pivotal role in growing the country’s energy carbon footprint. -

Investors'note

First - and Second-Quarter Reports INVESTORS’ NOTE for Year Ending March 2014 NOV. 2013 No.37 Security code Top Message To Our Shareholders Implementing “New Strategic Direction —Charting a New Path Toward Sustainable Growth” to Maximize Our Value as a Sogo Shosha Ken Kobayashi President and CEO Consolidated Operating Results for the Six Months Ended September 2013 (From April 1 to September 30, 2013) Achieved 62% of Full-Year Net Income Forecast Earnings Higher on a Year-Over-Year Basis I am pleased to address the shareholders In the first six months of the year ending of Mitsubishi Corporation (MC) through March 2014, the U.S. economy continued this newsletter. to experience a modest recovery, and in Let me begin by reporting on our Europe there were signs that the economy consolidated operating results for the six had bottomed out. Meanwhile, emerging months ended September 2013. economies, while also showing signs of 2 3 Top Message To Our Shareholders Dividend bottoming out in some quarters, generally rate of 62% of our full-year net income lacked strength in internal demand, forecast. The highlight of this result is that Two-Staged Dividend Policy Introduced resulting in a continued slowdown in all segments reported higher net income. growth. The Japanese economy, on the In the Machinery Group, automobile- ¥30 Interim Dividend per Share other hand, saw a moderate recovery, with related businesses performed steadily, the government policies underpinning the particularly in Asia, and the Metals Group For the three-year period from the year In accordance with this policy, we plan economy. -

![Toyota Tsusho Corporation Financial Highlights for the Three Months Ended June 30, 2020 [IFRS Basis] (Consolidated) July 31, 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0569/toyota-tsusho-corporation-financial-highlights-for-the-three-months-ended-june-30-2020-ifrs-basis-consolidated-july-31-2020-100569.webp)

Toyota Tsusho Corporation Financial Highlights for the Three Months Ended June 30, 2020 [IFRS Basis] (Consolidated) July 31, 2020

Toyota Tsusho Corporation Financial Highlights for the Three Months Ended June 30, 2020 [IFRS basis] (Consolidated) July 31, 2020 Listings Tokyo Stock Exchange (the first section), Nagoya Stock Exchange Security code 8015 URL https://www.toyota-tsusho.com/english/ Representative Ichiro Kashitani, President & CEO Contact Yasushi Aida General manager, Accounting Department Telephone +81 52-584-5482 Scheduled dates: Submission of quarterly securities report August 13, 2020 Dividend payout - Supplementary materials to the quarterly results Available Quarterly financial results briefings Yes (targeted at institutional investors and analysts) (Amounts rounded down to the nearest million yen) 1. Consolidated Financial Results for the Three Months ended June 30, 2020 (April 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020) (1) Operating Results (Percentage figures represent year-on-year changes) Total Profit before Profit attributable to Revenue Operating profit Profit comprehensive income taxes owners of the parent income Three Months ended million yen % million yen % million yen % million yen % million yen % million yen % June 30, 2020 1,193,982 (29.3) 19,139 (65.6) 25,995 (68.1) 16,386 (73.6) 13,393 (75.9) 35,159 (5.1) June 30, 2019 1,689,853 2.4 55,659 (1.5) 81,561 18.7 62,154 16.4 55,612 19.2 37,048 264.6 Diluted earnings per Basic earnings per share share Three Months ended yen yen June 30, 2020 38.07 - June 30, 2019 158.05 - Note: “Basic earnings per share” is calculated based on “Profit attributable to owners of the parent.” (2) Financial Position Equity attributable to Ratio of equity attributable to owners Total assets Total equity owners of the parent of the parent to total assets As of million yen million yen million yen % June 30, 2020 4,588,118 1,381,773 1,211,544 26.4 March 31, 2020 4,545,210 1,372,491 1,196,635 26.3 2. -

Fuel Cell Technology for Domestic Built Environment Applications: State Of-The-Art Review

FUEL CELL TECHNOLOGY FOR DOMESTIC BUILT ENVIRONMENT APPLICATIONS: STATE OF-THE-ART REVIEW Theo Elmer*, Mark Worall, Shenyi Wu and Saffa Riffat Architecture, Climate and Environment Research Group The University of Nottingham, NG7 2RD (UK) *corresponding author email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Fuel cells produce heat when generating electricity, thus they are of particular interest for combined heat and power (CHP) and combined cooling heat and power (CCHP) applications, also known as tri-generation systems. CHP and tri-generation systems offer high energy conversion efficiency and hence the potential to reduce fuel costs and CO2 emissions. This paper serves to provide a state-of-the-art review of fuel cell technology operating in the domestic built environment in CHP and tri-generation system applications. The review aims to carry out an assessment of the following topics: (1) the operational advantages fuel cells offer in CHP and tri-generation system configurations, specifically, compared to conventional combustion based technologies such as Stirling engines, (2) how decarbonisation, running cost and energy security in the domestic built environment may be addressed through the use of fuel cell technology, and (3) what has been done to date and what needs to be done in the future. The paper commences with a review of fuel cell technology, then moves on to examine fuel cell CHP systems operating in the domestic built environment, and finally explores fuel cell tri-generation systems in domestic built environment applications. The paper concludes with an assessment of the present development of, and future challenges for, domestic fuel cells operating in CHP and tri-generation systems. -

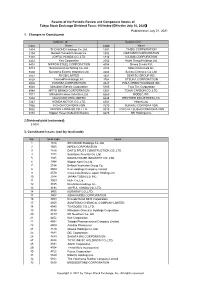

Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents 2

Results of the Periodic Review and Component Stocks of Tokyo Stock Exchange Dividend Focus 100 Index (Effective July 30, 2021) Published on July 21, 2021 1. Changes in Constituents Addition(18) Deletion(18) CodeName Code Name 1414SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 1801 TAISEI CORPORATION 2154BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 1802 OBAYASHI CORPORATION 3191JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. 1812 KAJIMA CORPORATION 4452Kao Corporation 2502 Asahi Group Holdings,Ltd. 5401NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION 4004 Showa Denko K.K. 5713Sumitomo Metal Mining Co.,Ltd. 4183 Mitsui Chemicals,Inc. 5802Sumitomo Electric Industries,Ltd. 4204 Sekisui Chemical Co.,Ltd. 5851RYOBI LIMITED 4324 DENTSU GROUP INC. 6028TechnoPro Holdings,Inc. 4768 OTSUKA CORPORATION 6502TOSHIBA CORPORATION 4927 POLA ORBIS HOLDINGS INC. 6503Mitsubishi Electric Corporation 5105 Toyo Tire Corporation 6988NITTO DENKO CORPORATION 5301 TOKAI CARBON CO.,LTD. 7011Mitsubishi Heavy Industries,Ltd. 6269 MODEC,INC. 7202ISUZU MOTORS LIMITED 6448 BROTHER INDUSTRIES,LTD. 7267HONDA MOTOR CO.,LTD. 6501 Hitachi,Ltd. 7956PIGEON CORPORATION 7270 SUBARU CORPORATION 9062NIPPON EXPRESS CO.,LTD. 8015 TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION 9101Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha 8473 SBI Holdings,Inc. 2.Dividend yield (estimated) 3.50% 3. Constituent Issues (sort by local code) No. local code name 1 1414 SHO-BOND Holdings Co.,Ltd. 2 1605 INPEX CORPORATION 3 1878 DAITO TRUST CONSTRUCTION CO.,LTD. 4 1911 Sumitomo Forestry Co.,Ltd. 5 1925 DAIWA HOUSE INDUSTRY CO.,LTD. 6 1954 Nippon Koei Co.,Ltd. 7 2154 BeNext-Yumeshin Group Co. 8 2503 Kirin Holdings Company,Limited 9 2579 Coca-Cola Bottlers Japan Holdings Inc. 10 2914 JAPAN TOBACCO INC. 11 3003 Hulic Co.,Ltd. 12 3105 Nisshinbo Holdings Inc. 13 3191 JOYFUL HONDA CO.,LTD. -

Integrated Report 2016 Report for the Next 10 Years, the Toyota Tsusho Group Group Tsusho Toyota for the Next 10 Years, the Will Evoke Our Ideal As “Be the Right ONE”

TOYOTA TSUSHO CORPORATION Integrated Report 2016 Fiscal year ended March 31, 2016 INTEGRATED REPORT 2016 REPORT INTEGRATED Next Steps for New Growth Competitive Edge in Business For the next 10 years, the Toyota Tsusho Group will evoke our ideal as “Be the Right ONE” Stakeholder Dialogue Editorial Policy Until now, Toyota Tsusho has published an Annual Report, which mainly covers report- ing focused on financial information, management strategies, performance and business activities, and a CSR Report, which mainly covers reporting focused on society and the environment. These two reports were published to deepen the understanding of Toyota Tsusho’s activities among all stakeholders. However, considering that both reports are closely related to one another and our goal of fostering an even stronger understanding of Toyota Tsusho among our stakeholders, we have started producing an Integrated Report from the fiscal year ended March 2015. In the preparation of this report, we have referred to the International Integrated Reporting Framework (International <IR> Framework) advo- cated by the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), the Sustainability Reporting Guidelines (version 4.0) of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Environmental Reporting Guidelines (2012 version) of the Ministry of the Environment in Japan and the ISO 26000 Guidance on Social Responsibility. In addition to reporting on management strategies, our performance, and business activities, the Integrated Report covers subjects such as Toyota Tsusho’s Approach to CSR, which guides our efforts to resolve social issues and contribute locally through our business activities. As Toyota Tsusho endeavors to drive sustained growth in these and other ways, we hope that this report will help to deepen your understanding of the company. -

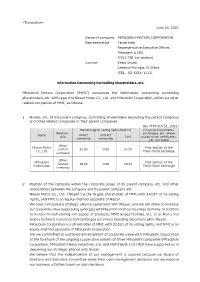

<Translation> June 24, 2021 Name of Company

<Translation> June 24, 2021 Name of company: MITSUBISHI MOTORS CORPORATION Representative: Takao Kato Representative Executive Officer, President & CEO (7211 TSE 1st section) Contact: Keiko Sasaki General Manager, IR Office (TEL.03-3456-1111) Information Concerning Controlling Shareholders, etc. Mitsubishi Motors Corporation (“MMC”) announces the information concerning controlling shareholders, etc. with regard to Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. and Mitsubishi Corporation, which are other related companies of MMC, as follows: 1 Names, etc. of the parent company, controlling shareholders (excluding the parent company) and other related companies or their parent companies (As of March 31, 2021) Percentage of voting rights held (%) Financial instruments Relation- exchanges, etc. where Name Direct Indirect ship Total issued share certificates, ownership ownership etc. are listed Other Nissan Motor First Section of the related 34.03 0.00 34.03 Co., Ltd. Tokyo Stock Exchange company Other Mitsubishi First Section of the related 20.02 0.00 20.02 Corporation Tokyo Stock Exchange company 2 Position of the company within the corporate group of its parent company, etc. and other relationships between the company and its parent company, etc. Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. (“Nissan”) is the largest shareholder of MMC with 34.03% of its voting rights, and MMC is an equity-method associate of Nissan. We have concluded a strategic alliance agreement with Nissan, and we will strive to increase our corporate value by pursuing synergies with Nissan in all of our business domains. In addition to mutual manufacturing and supply of products, MMC leases facilities, etc. to or from, and shares technical resources and exchanges personnel including executives with, Nissan. -

Classic Japanese Performance Cars Free

FREE CLASSIC JAPANESE PERFORMANCE CARS PDF Ben Hsu | 144 pages | 15 Oct 2013 | Cartech | 9781934709887 | English | North Branch, United States JDM Sport Classics - Japanese Classics | Classic Japanese Car Importers Not that it ever truly went away. But which one is the greatest? The motorsport-derived all-wheel drive system, dubbed ATTESA Advanced Total Traction Engineering System for All-Terrainuses computers and sensors to work out what the car is doing, and gave the Skyline some particularly special abilities — famously causing some rivalry at the Nurburgring with a few disgruntled Classic Japanese Performance Cars engineers…. The latest R35 GT-R, for the first time a stand-alone model, grew in size, complexity and ultimately speed. A mid-engined sports car from Honda was always going to be special, but the NSX went above and beyond. Honda managed to convince Ayrton Senna, who was at the time driving for McLaren Honda, to assess a late-stage prototype. Honda took what he said onboard, and when the NSX went on sale init was a hugely polished and capable machine. Later cars, especially the uber-desirable Type-R model, were Classic Japanese Performance Cars to perfection. So many Imprezasbut which one to choose? All of the turbocharged Subarusincluding the Legacy and even the bonkers Forrester STi, have got something inherently special to them. Other worthy models include the special edition RB5, as well as the Prodrive fettled P1. All will make you feel like a rally driver…. Mazda took all the best parts of the classic British sports car, and built them into a reliable and equally Classic Japanese Performance Cars package. -

Into the Future on Three Wheels

Mitsubishi The 9th Grand Prix Winner A Bimonthly Review of the Mitsubishi Companies and Their People Around the World 2009-2010 Asian Children's2008- Enikki Festa 2009 Winners December & January Grand Prix Japan Humans are social beings. People live in groups. We Bangladeshis like to live with our parents, our brothers and sisters, our grandparents, and other relatives. In our family, I live with my brother, my parents, and my grandmother. We share each other’s joys and sorrows. That makes our lives fulfilling. Cycling * The above sentences contained in this Enikki has been translated from Bengali to English. Into the Future The 9th Grand Prix Winner on Three Wheels Sadia Islam Mowtushy Age:11 Girl People’s Republic of Bangladesh “Wrapping Up the Year with Toshikoshi Soba” oba is a Japanese noodle that is eaten in various ways longevity, because it is long and thin. There are many other depending on the season. In summer, soba is served cold explanations and no single theory can claim to be the definitive S and dipped in a chilled sauce; in winter, it comes in a hot truth, but this only adds to the mystique of toshikoshi soba. broth. Soba is often garnished with tasty tidbits, such as tempura shrimp, or with a bit of boiled spinach to add a touch of color. Soba has been a favorite of Japanese people for centuries and the popular buckwheat noodle has even secured a role in various Japanese traditions, including the New Year’s celebration. Japanese people commonly eat soba on New Year’s Eve, when the old year intersects with the new year, and this is known as toshikoshi or “year-crossing” soba.