6 Hanoverian London: the Making of a Service Town1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets the Tower Was the Seat of Royal

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets The Tower was the seat of Royal power, in addition to being the Sovereign’s oldest palace, it was the holding prison for competitors and threats, and the custodian of the Sovereign’s monopoly of armed force until the consolidation of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich in 1805. As such, the Tower Hamlets’ traditional provision of its citizens as a loyal garrison to the Tower was strategically significant, as its possession and protection influenced national history. Possession of the Tower conserved a foothold in the capital, even for a sovereign who had lost control of the City or Westminster. As such, the loyalty of the Constable and his garrison throughout the medieval, Tudor and Stuart eras was critical to a sovereign’s (and from 1642 to 1660, Parliament’s) power-base. The ancient Ossulstone Hundred of the County of Middlesex was that bordering the City to the north and east. With the expansion of the City in the later Medieval period, Ossulstone was divided into four divisions; the Tower Division, also known as Tower Hamlets. The Tower Hamlets were the military jurisdiction of the Constable of the Tower, separate from the lieutenancy powers of the remainder of Middlesex. Accordingly, the Tower Hamlets were sometimes referred to as a county-within-a-county. The Constable, with the ex- officio appointment of Lord Lieutenant of Tower Hamlets, held the right to call upon citizens of the Tower Hamlets to fulfil garrison guard duty at the Tower. Early references of the unique responsibility of the Tower Hamlets during the reign of Bloody Mary show that in 1554 the Privy Council ordered Sir Richard Southwell and Sir Arthur Darcye to muster the men of the Tower Hamlets "whiche owe their service to the Towre, and to give commaundement that they may be in aredynes for the defence of the same”1. -

William Murduck, 1834 – 1895

William Murduck, 1834 – 1895 William Murduck was born in his parents’ home in Bethnal Green (London), England, probably very early in 1834. His parents – Thomas and Mary Ann [nee Coleman], crossed parish boundaries from Bethnal Green to Stepney when they had their son baptised at St. Dunstan’s, the church of the Parish of Stepney, on 9 February 1834.1 Thomas the father was a bricklayer/builder (born 1795) who had moved in to east London probably in the fall of 1825, a little more than eight years before William’s birth. Thomas had been married to Mary Coleman in 1821, in the Parish of Writtle (near Chelmsford in Essex County, north and east of London about 40 miles). Two surviving children who had been born in Writtle – John (born 1822) and Eliza (born 1826) made the move with him. In Bethnal Green, Thomas (1829), Mary Ann Lucy (1831), then William, Elizabeth Sarah (1836), George (1839), Charles (1842), and Edward (1843) were born. William came from a long line of bricklayer/builders who had lived in and worked out of Writtle ever since the late 1600s. His great, great grandfather John Murduck (baptised 14 January 1699) was a bricklayer. William’s great grandfather John Murduck (baptised 5 May 1734) was a bricklayer. So was his grandfather Thomas Murduck (baptised 18 September 1765). William’s uncle – his father’s younger brother, Robert John (known as John, baptised in the parish of Hornchurch, Essex, on 29 April 1804), was also a bricklayer. It`s probable that William’s father and uncle operated a ‘family style business’ constructing and repairing residential buildings in east London and west Essex for many years. -

Billingsley Fourty Shillings Apiece Item I Give Unto My Aforesayd Brother Mr

Descendants by Generation 7 Mar 2015 Katherine WHITLOCK (1622-1690) 1. Katherine WHITLOCK was born in 1622 in London, MDX.1 She died in 1690 in London.1 She married Thomas JORDAN. 1690: WILL OF KATHERINE (WHITLOCK) JORDEN In the name of God Amen I Katherine Jorden of London widdow being weake in body but of sound mind and memory (blessed be God doe make and ordaine this my last will and Testament And as touching the Temporall Estate wherewith God hath Graciously blessed mee I doe Will and devise the same as followeth Imprimus I give unto Doctor Samuell Annesly and to my brother Mr. John Whitlock the sume of one hundred pounds of lawfull oney of England to bee payd nto them within one yeare next after my decease Uppon trust in the in them .....ed that they or the survivour of them shall give and dispose the same to such and soe many poore Godly Ministers and in such proportions as I shall either in writeing under my hand or by word of mouth before witnesses nominiate and apppoint to receive the same within one yeare next after my decease And if any of these persons that I shall nominate dye before they have received the proportion by mee appointed them Then my said Trustees are to pay the same to such other person or persons in his or their stead as my sayd Trustees shall thinke fitt Item I further give to the said Doctor Annesley and my brother Whitlock the sume of Thirty pounds like money to bee payd them within the Time aforesayd uppon Trust that they or the Survivour of them doe likewise give and dispos of the same to such and soe -

London Parish Boundary Markers and Other Administrative Boundary Markers in London by Mike Horne FRGS FRSA

Version at 2 November 2014 London parish boundary markers and other administrative boundary markers in London by Mike Horne FRGS FRSA Parish boundary markers are not yet extinct in the London area, but probably where they were not clear. Nevertheless the vast majority of boundaries were fewer than five per cent of their historic number survive; some of these are natural features in the landscape though trees and hedges specifically for threatened by redevelopment work or are deteriorating badly through lack of boundary identification purposes might be added. The custom of marking cer- maintenance. It seems a good time to record the survivors, and their condition, tain boundary points with trees, allegedly called Gospel Trees, is remembered by and at the same time put down a few words to describe them. the district name Gospel Oak (in Hampstead) after such a tree in Southampton Before going into detail about the markers it is first necessary to make a few Road, forming the boundary printedbetween St Pancras and Hampstead. It was appar- observations about what a ‘parish’ was, and why one would want to provide ently the practice to read from the gospels during perambulations. markers at boundaries. The divisionbe of the country into parishes was a lengthy and unsystematic Historically, England was not densely populated and nor was their any con- process beginning with the arrival of the Christian missionaries in the seventh ception of central government (at least, not beyond allegiance to the monarch centuryto and being more or less complete by the thirteenth century by which and its occasional demands for men or money to facilitate war). -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES WESTMINSTER BOARD of GUARDIANS WEBG Page 1 Reference Description Dates CITY of WESTMINSTER UNION Bo

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 WESTMINSTER BOARD OF GUARDIANS WEBG Reference Description Dates CITY OF WESTMINSTER UNION Board WEBG/CW/001 Board minutes (Indexed) 1913 Apr - 1 volume 1914 Apr WEBG/CW/002 Board minutes (Indexed) 1914 Apr - 1 volume 1915 Mar WEBG/CW/003 Board minutes (Indexed) 1915 Apr - 1 volume 1916 Apr WEBG/CW/004 Board minutes (Indexed) 1916 May - 1 volume 1917 Apr WEBG/CW/005 Board minutes (Indexed) 1917 May - 1 volume 1918 Apr WEBG/CW/006 Board minutes (Indexed) 1918 May - 1 volume 1919 Apr WEBG/CW/007 Board minutes (Indexed) 1919 Apr - 1 volume 1920 Mar WEBG/CW/008 Board minutes (Indexed) 1920 Apr - 1 volume 1921 Mar WEBG/CW/009 Board minutes (Indexed) 1921 Apr - 1 volume 1922 Mar WEBG/CW/010 Board minutes (Indexed) 1922 Apr - 1 volume 1923 Mar WEBG/CW/011 Board minutes (Indexed) 1923 Apr - 1 volume 1924 Mar WEBG/CW/012 Board minutes (Indexed) 1924 Apr - 1 volume 1925 Mar WEBG/CW/013 Board minutes (Indexed) 1925 Apr - 1 volume 1926 Mar LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 WESTMINSTER BOARD OF GUARDIANS WEBG Reference Description Dates WEBG/CW/014 Board minutes (Indexed) 1926 Apr - 1 volume 1927 Mar WEBG/CW/015 Board minutes (Indexed) 1927 Apr - 1 volume 1928 Mar WEBG/CW/016 Board minutes (Indexed) 1928 Apr - 1 volume 1929 Mar WEBG/CW/017 Board minutes (Indexed) 1929 Apr - 1 volume 1930 Mar Committees WEBG/CW/018/001 Accounts Sub-Committee: minutes 1924 Jan - 1 volume 1927 Nov WEBG/CW/018/002 Accounts Sub-Committee: minutes 1927 Nov - 1 volume 1930 Mar WEBG/CW/019/001 Buckingham Palace Road Workhouse 1913 Apr -

London Metropolitan Archives Saint Dunstan In

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 SAINT DUNSTAN IN THE WEST: CITY OF LONDON P69/DUN2 Reference Description Dates PARISH REGISTERS P69/DUN2/A/001/MS10342 Register general, containing baptisms 1558- 1558 - 1631/2 Not available for general access 1631/2, marriages 1559/60-1631/2, and burials Please use microfilm 1558-1631/2. available online via Original register may be consulted. www.ancestry.co.uk 1 volume Former Reference: MS 10342 P69/DUN2/A/002/MS10343 Register general, containing baptisms 1599- 1558 - 1622 Not available for general access 1622, marriages 1559/60-1622, and burials Please use microfilm 1558-1614. available online via Paper register. www.ancestry.co.uk 1 volume Former Reference: MS 10343 P69/DUN2/A/003/MS10344 Register general, containing baptisms 1623-45, 1623 - 1645 Not available for general access marriages 1625-45, and burials 1623-45. Please use microfilm Paper register. available online via 1 volume www.ancestry.co.uk Former Reference: MS 10344 P69/DUN2/A/004/MS10345 Register general, containing baptisms 1632/3- 1632 - 1669/70 Not available for general access 69/70, marriages 1632-58, and burials 1632-69. Please use microfilm Includes, from 1653-5, publication of marriages available online via according to the Act of Parliament of 24 August www.ancestry.co.uk 1653 ('Commonwealth marriages'). Original register may be consulted. 1 volume, vellum Former Reference: MS 10345 P69/DUN2/A/005/MS10346 Register general, containing baptisms 1645-56, 1645 - 1656 Not available for general access marriages 1645-53, and burials 1645-56. Please use microfilm Entries of marriages, from 1648 to 1650, are available online via defective. -

London Metropolitan Archives Middlesex Sessions

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 MIDDLESEX SESSIONS: COUNTY ADMINISTRATION MA Reference Description Dates COUNTY ADMINISTRATION: LUNATIC ASYLUMS Maintenance of lunatics MA/A/C/001 Alphabetical register of lunatics, giving name, 1860 - 1888 date of admission, which asylum, 'how disposed of' MA/A/C/002 Register of lunatics Gives name, date of 1871 - 1877 maintenance order, to what asylum sent, 'how disposed of' MA/A/C/003/1853 Applications for maintenance of lunatics 1853 8 MA/A/C/003/1865 Applications for maintenance of lunatics 1865 53 MA/A/C/003/1866 Applications for maintenance of lunatics 1866 73 MA/A/C/003/1867 Applications for maintenance of lunatics 1867 46 MA/A/C/003/1868 Applications for maintenance of lunatics 1868 47 MA/A/C/003/1869 Applications for maintenance of lunatics 1869 64 MA/A/C/003/1870 Applications for maintenance of lunatics 1870 8 MA/A/C/003/1872 Applications for maintenance of lunatics: 1872 Criminal lunatics 8 MA/A/C/003/1873 Applications for maintenance of lunatics: 1873 Matilda or Louisa Lewis 1 MA/A/C/003/1874 Applications for maintenance of lunatics 1874 6 LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 MIDDLESEX SESSIONS: COUNTY ADMINISTRATION MA Reference Description Dates MA/A/C/003/1875/001 Applications for maintenance of lunatics (B-E) 1875 (items numbered 1875/001-024) MA/A/C/003/1875/025 Applications for maintenance of lunatics (E-M) 1875 (items numbered 1875/025-047) MA/A/C/003/1875/048 Applications for maintenance of lunatics (M-R) 1875 (items numbered 1875/048-060) MA/A/C/003/1875/061 Applications for maintenance -

Protestation Returns Document

WEST MIDDLESEX FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY THE 1641 - 42 PROTESTATION OF MIDDLESEX Oliver Cromwell outside the Houses of Parliament. The oath In 1641 Parliament decreed that ALL males over the age of 18 should swear an “Oath of Allegiance” to the Protestant Church of England, Parliament and the King Charles. Although many parts of England have no record of these returns, the returns for Middlesex include 16,600 names, which it is estimated are 80% of the total returns due for the county. The following is the oath which each male had to swear:- I,......................, do, in the Presence of Almighty God, promise, vow, and protest to maintain and defend, as far as lawfully I may, I with my Life, Power, and Estate, the true Reformed Protestant Religion, expressed in the Doctrine of the Church of England, against all Popery and Popish Innovations, within this Realm, contrary to the same Doctrine, and according to the Duty of my Allegiance, to His Majesty's Royal Person, Honour, and Estate, as also the Power and Privileges of Parliaments, the lawful Rights and Liberties of the Subjects, and every Person that maketh this Protestation, in whatsoever he shall do in the lawful Pursuance of the same; and to my power, and as far as lawfully I may, I will oppose and by all good Ways and Means endeavour to bring to condign Punishment all such as shall, either by Force, Practice, Counsels, Plots, Conspiracies, or otherwise, do any Thing to the contrary of any Thing in this present Protestation contained; and further, that I shall, in all just and honourable Ways, endeavour to preserve the Union and Peace betwixt the Three Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland: and neither for Hope, Fear, nor other Respect, shall relinquish this Promise, Vow, and Protestation." © House of Lords Records Office. -

Post Office London Bay-Bea

744 BAY-BEA POST OFFICE LONDON BAY-BEA Baynet1 David Willinm, timber merchant, eee Worrell & Baynee Beabr Ernest, hai.rdreslll!r, 101 Boundary road NW 'Bea.n B.Ltd. cabinet makers, 5o Grsat E118teru Bt E C ; 19 Old NIMai Baynes Donald,M'.A.,M.D.pbysn-45 Up. Brook: et W-TN6366Gerrard Beak W.G.&Co. ~<birt manufrs.14Monkwell stE C-TN1o8680entral at root E & 63 Scrutton street E C-T N 1749 London Wall BaynBil Edwant Neil, t!Olicitor, 11 Bedford row WC Beak Elizabeth (Mrs.), apartments, 151 Goldhurst terrace NW Beal\ & Ringwood {B. & R.), patentees & m.Uell' nf aee'Yiene 111 BaynBil Ernest Spencer, solicitor, 8 Union court., Old Broad street E C Beak SamnA\, bootmaker, 1q West Enol lane, K ilbum NW appamtnP, 3ZA, St. Mary'11 roarl., Plai.Htow E-T N Z79 East; Baynes F're!lk:.JII8. ironmonger.~ibmltarraage pa.tentee,constructOJ Beakbane Henry,leather manufactr. Ru11g at. West India. dock rdE Bean R. F. & Co. lRdies' neckwear manuf~<cturers, 'to 6 Bridge- of cooking apparatus for hotel11 &c. 99 St. Pan!' a rd. Hi!Zbbury N -TA. •· Beak bane, Pop"; T N 36g4 East water place E C -T N 4171 Cit.v Baynes Henry Richard, •Eagle tavPrn' P.H. z Shepherdess walk N Beakes George Tbom~~o~~, bnotmak:er, 34 Devonshire street E Bean & Bon, litbogmpbPrs, color & printenll Bay ne!! John, beer retailer, 88 Lambeth wnlk SE Beq.l (Edmnnd)&Davey,solicitors, 14Devonshiresq E C-TNz5o City engrave I'll & manufg.statmners.&, Golden la E C- 747 Cenk'll Baynel! NormanHepburn. -

London Metropolitan Archives

London Metropolitan Archives Guide to Major Family History Resources City of London How to use this guide London Generations is a guide to our major family history sources and currently includes the following types of records: Anglican parish registers of baptisms, marriages and burials for around 800 parishes within the former counties of London and Middlesex; Bishops transcripts of parish registers; Anglican parish Poor Law registers; non-conformist baptism and marriage registers; land tax assessments; admission and creed registers for workhouses run by Boards of Guardians; London County Council School admission and discharge registers and electoral registers for the counties of London and Middlesex. Many of the registers you can see here have been digitised and are also available on the Ancestry.co.uk website, where individual names can be searched in most cases. These lists provide details of the holdings of each of the various registers we hold, and the reference number for the material if you are visiting LMA. 2 London Generations Database CITY OF LONDON INDEX TO PARISHES Parish Name First Register ALL HALLOWS THE GREAT: CITY OF LONDON 1667 AT LMA: P69/ALH7 ALL HALLOWS THE LESS: CITY OF LONDON 1558 AT LMA: P69/ALH8 ALL HALLOWS, BREAD STREET: BREAD STREET, CITY OF LONDON 1538 AT LMA: P69/ALH2 ALL HALLOWS, HONEY LANE: HONEY LANE, CITY OF LONDON 1538 AT LMA: P69/ALH3 ALL HALLOWS, LOMBARD STREET: LOMBARD STREET, CITY OF LONDON 1550 AT LMA: P69/ALH4 ALL HALLOWS, LONDON WALL: LONDON WALL, CITY OF LONDON 1559 AT LMA: P69/ALH5 ALL HALLOWS, -

Land Tax Assessments for London and Middlesex

RESEARCH GUIDE Land Tax Assessments for London and Middlesex LMA Research Guide 9: Land Tax Assessments for London and Middlesex CONTENTS Introduction Background Records at LMA City of London Middlesex Kent Surrey Introduction London Metropolitan Archives holds land tax assessments for the City of London, the county of Middlesex (including most Westminster parishes), and certain parishes in Kent and Surrey now in inner London. Almost all of these assessments have been digitised and made available on the Ancestry website. Please see the database titled London, England, Land Tax Records, 1692-1932. Background The first assessments of 1692-3 were made under the terms of 'An Act for granting to their Majesties an aid of four shillings in the pound for one year for carrying on a vigorous war against France'[4 William & Mary c.1, 1692/3]. The Act specified that real estate and personal property, that is buildings and moveable goods as well as land, were to be taxed. It nominated for each borough and county in England and Wales the local commissioners who were to supervise the assessments and local collection. The tax was voted annually, usually in the spring, until 1798 when it was transformed into a permanent tax but was redeemable on payment of a lump sum. It was levied on a number of different bases: as a pound rate between 1693 and 1696, as a 4 shillings assessment supplemented by a poll tax in 1697 and from 1698-1798 on the system whereby each county or borough was given a fixed sum to collect. In 1949 redemption became compulsory on property changing hands and in 1963 all unredeemed land tax was abolished. -

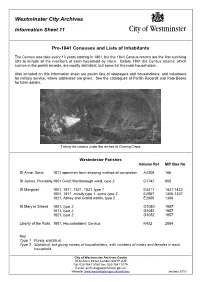

Pre-1841 Censuses and Lists of Inhabitants.Pdf

Westminster City Archives Information Sheet 11 Pre-1841 Censuses and Lists of Inhabitants The Census was take every 10 years starting in 1801, but the 1841 Census returns are the first surviving lists to include all the members of each household by name. Before 1841 the Census returns, which survive in the parish records, are mostly statistical, but some list the main householder. Also included on this information sheet are parish lists of ratepayers and householders, and volunteers for military service, where addresses are given. See the catalogues of Parish Records and Rate Books for fuller details. Taking the census under the arches at Charing Cross Westminster Parishes Volume Ref M/F Box No St Anne, Soho 1811 specimen form showing method of completion A2308 166 St James, Piccadilly 1801 Great Marlborough ward, type 2 D1742 855 St Margaret 1801, 1811, 1821, 1831, type 1 E3311 1431-1433 1801, 1811, mostly type 1, some type 2 E2867 1306-1307 1821, Absey and Grand wards, type 2 E2865 1306 St Mary le Strand 1801, type 2 G1050 1957 1811, type 2 G1051 1957 1821, type 2 G1052 1957 Liberty of the Rolls 1801, Householders’ Census K432 2084 Key Type 1 Purely statistical. Type 2 Statistical, but giving names of householders, with numbers of males and females in each household. City of Westminster Archives Centre 10 St Ann’s Street, London SW1P 2DE Tel: 020-7641 5180, fax: 020-7641 5179 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.westminster.gov.uk/archives January 2010 Westminster City Archives Pre-1841 Censuses Information Sheet 11 and Lists of Inhabitants St George Hanover Square There is a census for St George’s parish taken around 1790 at London Metropolitan Archives, in two volumes, ref TC/STG/1-2 (on microfilm, ref X045/001).