City of London Spatial Classification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central London Plan Bishopsgate¬Corridor Scheme Summary

T T T T D S S S R Central London Plan EN H H H H H RE G G BETHNAL SCLATER S Bishopsgate¬corridor Scheme Summary I T H H ShoreditchShoreditch C Key T I HHighigh StreetStreet D E Bus gate – buses and cyclists only allowed R O B through during hours of operation B H R W R OR S I I Q Q SH C IP C S K Section of pavement widened K ST N T E Y O S T L R T A L R G A U Permitted turns for all vehicles DPR O L I N M O B L R N O F S C O E E S P ST O No vehicular accessNSN except buses P M I A FIF E M Email feedback to: T A E streetspacelondon@tfl.gov.uk G R S C Contains Ordnance Survey data LiverpoolLiverpool P I © Crown copyright 2020 A SStreettreet O L H E MoorgateM atete S ILL S T I ART E A B E T RY LANAN R GAG E R E O L M T OOO IVE * S/BS//B onlyoonlyy RP I OO D M L S O T D S LO * N/BN//B onlyoonlyy L B ND E S O ON S T RNR W N E A E LL X T WORM A WO S OD HOUH T GATEG CA T T M O R S R E O U E H S M NDN E G O T I T I A LE D H O D S S EL A G T D P M S B I A O P E T H R M V C . -

Committee(S) Dated: Planning and Transportation

Committee(s) Dated: Planning and Transportation 23rd June 2020 Subject: Public Delegated decisions of the Chief Planning Officer and Development Director Report of: For Information Chief Planning Officer and Development Director Summary Pursuant to the instructions of your Committee, I attach for your information a list detailing development and advertisement applications determined by the Chief Planning Officer and Development Director or those so authorised under their delegated powers since my report to the last meeting. In the time since the last report to Planning & Transportation Committee Thirty-Nine (39) matters have been dealt with under delegated powers. Sixteen (16) relate to conditions of previously approved schemes. Six (6) relate to works to Listed Buildings. Two (2) applications for Non-Material Amendments, Three (3) applications for Advertisement Consent. One (1) Determination whether prior app required, Two (2) applications for works to trees in a conservation area, and Nine (9) full applications which, including Two (2) Change of Uses and 396sq.m of floorspace created. Any questions of detail arising from these reports can be sent to [email protected]. Details of Decisions Registered Address Proposal Applicant/ Decision & Plan Number & Agent name Date of Ward Decision 20/00292/LBC 60 Aldersgate (i) Replacement of single Mackay And Approved Street London glazed, steel framed Partners Aldersgate EC1A 4LA double height windows 04.06.2020 with double glazed aluminium framed windows (north and south facing elevations, first and second sub-podium levels) (ii) Retention of existing frames and replacement of single glazing with double glazing (north and south facing elevations, first sub-podium level) (iii) Retention of frames and replacement double glazed units (south and west facing elevations, second sub-podium level). -

June 2015 BRIEFING

LIVERY June 2015 BRIEFING From the Chairman of the Livery Committee. having by then served as Sheriff. The Court together with masters’ names, bio’s, photos, then decided that it would support Andrew company information and other links go to Dear Clerk, Parmley for election as Lord Mayor for 2016- www.liverycompanies.info 17. Herewith the latest edition of the Magna Carta 800 celebrations bi-monthly Livery Briefing, for onward With respect to the Shrievalty in 2016-17 800 years to the day since the sealing of distribution to your Livery, please. This edition the Livery Committee has given favourable Magna Carta, on 15 June Her Majesty the of the bi-monthly Briefing includes a summary consideration to supporting the possibility of Queen led a celebration in the meadow at of those topics discussed at the meeting two Aldermen holding the office of Sheriff in Runnymede attended by other senior of the Livery Committee on 10 June 2015, that year. members of the Royal Family, the Archbishop together with an update on more general of Canterbury, the Prime Minister, and subjects of interest to liverymen. The full letter may be downloaded here. many guests which included a large City delegation of livery masters and others led The content draws heavily on the News Election of Sheriffs by the Lord Mayor. pages at the Livery Committee website, Wednesday 24 June will see the annual where you can find details and links to a election of Sheriffs. At the closing date for The City of London played an active role in host of livery related information. -

London Metropolitan Archives Elder, Henry

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 ELDER, HENRY WESTON ACC/0412 Reference Description Dates PROPERTY RECORDS HORNSEY ACC/0412/A/01/001 Baron court document, manor of Topsfields 1787 Mar 31 alias Hornsey Surrender of William King of property within the manor to the uses of his will. 1 document ACC/0412/A/01/002 Copy extract 1792 Apr 27 Admission of Hannah King, widow, to a copyhold messuage formerly built on the waste of the manor. [Manor of Topsfield alias Topsfield Hall in Harringay alias Hornsey?]. 1 document ACC/0412/A/01/003 Certificate for redemption of land tax 1803 Apr 28 Parties: James Luitter, Esquire, William Marmaduke Sellon, Esquire and William Adams, Hornsey, Crounch End for the redemption of £2 and 10 shillings land tax. Includes details of premises, names of occupiers and proprietor and sum and rent charges for premises in Crouch End, Hornsey. 1 document ACC/0412/A/01/004 Bond of indemnity 1803 Jul 07 A sum of £1,000 to be paid to William Henry Crowder, Finsbury Square, London from Dorothy Bruce, Crouch End, Middlesex, relating to property in the town parish precincts and territories of Hornsey. 1 document ACC/0412/A/01/005 Grant of an annuity 1833 May 02 Annuity of £42 and conveyance and assignment of the interests of C. Basan under the wills of his late father and uncle in trust for securing the same annuity. (Property at Crouch End, Hornsey). 1 document LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 ELDER, HENRY WESTON ACC/0412 Reference Description Dates ACC/0412/A/01/006 Declaration of Caroline Elizabeth Lecaan, 14 1868 Mar 25 Church Road, West Hackney, Middlesex Wife of George Leccan. -

Chaucer’S Birth—A Book Went Missing

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. •CHAPTER 1 Vintry Ward, London Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience. — James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man In the early 1340s, in Vintry Ward, London— the time and place of Chaucer’s birth— a book went missing. It wasn’t a very important book. Known as a ‘portifory,’ or breviary, it was a small volume containing a variety of excerpted religious texts, such as psalms and prayers, designed to be carried about easily (as the name demonstrates, it was portable).1 It was worth about 20 shillings, the price of two cows, or almost three months’ pay for a carpenter, or half of the ransom of an archer captured by the French.2 The very presence of this book in the home of a mer- chant opens up a window for us on life in the privileged homes of the richer London wards at this time: their inhabitants valued books, ob- jects of beauty, learning, and devotion, and some recognized that books could be utilized as commodities. The urban mercantile class was flour- ishing, supported and enabled by the development of bureaucracy and of the clerkly classes in the previous century.3 While literacy was high in London, books were also appreciated as things in themselves: it was 1 Sharpe, Calendar of Letter- Books of the City of London: Letter- Book F, fol. -

Prisoners in LUDGATE Prison., in the City of London

1565 ] iliomas Nasb, fornterly, and late of Braintree, in tbc county SECOND NOTICE. of Essex, calmjtft-Kiaker. George Yoomans, lat,«of No. 7, John-street, CrutcUod-friar;*,' ChUrles Moore, formerly, anulrtte of Peckham, in the county and forrurrly' of No, 2, Hart-street, both in the city ef of Surrey, carpenter-. • London, taylor. Thomas SiavthaiVt, -i'lrt-mefjy of Seal, and late t>f Greenwich, .Tames Devilt, late of No. 73, Snowhill, and formerly of No. iwthetminiry wf iCcjrt, tdge-^tool-niaher. 75, Lombard-street, both iu the city of London^ trust*- 'William Masters, formerly of •Bond-str-cet, imtl Iste of Dover- nvaker. stri-ct, Saint Geortje's-fielas, Sbitthwsurh, «hoe-u«iker. James-Keys, late of No. 7, Red Lion-court, Charter-house- tsamrtel Meek,formerly, and late of Chuvch-stetjtJt, Horseley- lane, in -the county of Middlesex, and of Newgate-market, dow.ii, alid of Webb-Street,, Bcrnwndsey, both iu tlie county London, aud formerly of No. 1, Red Lion-court, Cock- of Surrey., 'cooper. lane, Giltspur-street, London, poulterer. ^heopbilus Jftnstun, formerly oT Clafh-Fair, W«st. Smith field, Anu Longs^aff, late of Prujean-square, Oldibailey, and for- -and of Totteubarn-TOuTt-roatl, both in the Bounty of merly of-the Belle Sauvage*yard, Ludgate-hill, both in the "Middlesex, tailor. city of London, widow. 3eseph Hy&m, formerly rif'tber-ttytrf Bristol, and late of William Drought, late of Red Lion-street, .Olerkenwell, and • A'bergavemry, iuthe county of Mouiuouth, shopkeeper aud formerly of Baltic-street, Old-street, both in the county of jeweller. -

Historic Erie Canal Aqueduct & Broad Street Corridor

HISTORIC ERIE CANAL AQUEDUCT & BROAD STREET CORRIDOR MASTER PLAN MAY 2009 PREPARED FOR THE CITY OF ROCHESTER Copyright May 2009 Cooper Carry All rights reserved. Design: Cooper Carry 2 Historic Erie Canal AQUedUct & Broad Street Corridor Master Plan HISTORIC ERIE CANAL AQUEDUCT & BROAD STREET CORRIDOR 1.0 MASTER PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 23 1.2 INTRODUCTION 27 1.3 PARTICIPANTS 33 2.1 SITE ANALYSIS/ RESEARCH 53 2.2 DESIGN PROCESS 57 2.3 HISTORIC PRECEDENT 59 2.4 MARKET CONDITIONS 67 2.5 DESIGN ALTERNATIVES 75 2.6 RECOMMENDATIONS 93 2.7 PHASING 101 2.8 INFRASTRUCTURE & UTILITIES 113 3.1 RESOURCES 115 3.2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Historic Erie Canal AQUedUct & Broad Street Corridor Master Plan 3 A city... is the pulsating product of the human hand and mind, reflecting man’s history, his struggle for freedom, creativity and genius. - Charles Abrams VISION STATEMENT: “Celebrating the Genesee River and Erie Canal, create a vibrant, walkable mixed-use neighborhood as an international destination grounded in Rochester history connecting to greater city assets and neighborhoods and promoting flexible mass transit alternatives.” 4 Historic Erie Canal AQUedUct & Broad Street Corridor Master Plan 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CREATING A NEW CANAL DISTRICT Recognizing the unrealized potential of the area, the City of the historic experience with open space and streetscape initiatives Rochester undertook a planning process to develop a master plan which coordinate with the milestones of the trail. for the Historic Erie Canal Aqueduct and adjoining Broad Street Corridor. The resulting Master Plan for the Historic Erie Canal Following the pathway of the original canal, this linear water Aqueduct and Broad Street Corridor represents a strategic new amenity creates a signature urban place drawing visitors, residents, beginning for this underutilized quarter of downtown Rochester. -

Community and Childrens Services Terms of Reference

WOOTTON, Mayor RESOLVED: That the Court of Common Council holden in the Guildhall of the City of London on Thursday 19th April 2012, doth hereby appoint the following Committee until the first meeting of the Court in April, 2013. COMMUNITY & CHILDREN’S SERVICES COMMITTEE 1. Constitution A Ward Committee consisting of, two Aldermen nominated by the Court of Aldermen up to 33 Commoners representing each Ward (two representatives for the Wards with six or more Members regardless of whether the Ward has sides), those Wards having 200 or more residents (based on the Ward List) being able to nominate a maximum of two representatives a limited number of Members co-opted by the Committee (e.g. the two parent governors required by law) In accordance with Standing Order Nos. 29 & 30, no Member who is resident in, or tenant of, any property owned by the City of London and under the control of this Committee is eligible to be Chairman or Deputy Chairman. 2. Quorum The quorum consists of any nine Members. [N.B. - the co-opted Members only count as part of the quorum for matters relating to the Education Function] 3. Membership 2012/13 ALDERMEN 1 The Hon. Philip John Remnant, C.B.E. 1 New Alderman for the Ward of Aldgate COMMONERS 7 The Revd. Dr. Martin Dudley ………………………………………………………………….Aldersgate 2 Joyce Carruthers Nash, O.B.E., Deputy .........................................................................Aldersgate 4 Hugh Fenton Morris .......................................................................................................Aldgate -

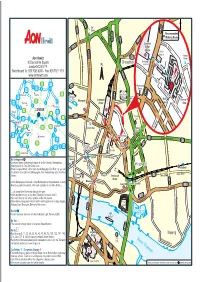

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

861 Sq Ft Headquarters Office Building Your Own Front Door

861 SQ FT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDING YOUR OWN FRONT DOOR This quite unique property forms part of the building known as Rotherwick House. The Curve comprises a self-contained building, part of which is Grade II Listed, which has been comprehensively refurbished to provide bright contemporary Grade A office space. The property — located immediately to the east of St Katharine’s Dock and adjoining Thomas More Square — benefits from the immediate area which boasts a wide variety of retail and restaurant facilities. SPECIFICATION • Self-contained building • Generous floor to ceiling heights • New fashionable refurbishment • Full-height windows • New air conditioning • Two entrances • Floor boxes • Grade II Listed building • LG7 lighting with indirect LED up-lighting • Fire and security system G R E A ET T THE TEA TRE E D S A BUILDING OL S T E R SHOREDITCH N S HOUSE OLD STREET T R E E T BOX PARK AD L RO NWEL SHOREDITCH CLERKE C I HIGH STREET T Y R G O O A S D W S F H A O E R L U A L R T AD T H I O R T R N A S STEPNEY D’ O O M AL G B N A GREEN P O D E D T H G O T O WHITECHAPEL A N N R R R O D BARBICAN W O CHANCERY E A FARRINGDON T N O LANE D T T E N H A E M C T N O C LBOR A D O HO M A IGH MOORGATE G B O H S R R U TOTTENHAM M L R LIVERPOOL P IC PE T LO E COURT ROAD NDON WA O K A LL R N R H STREET H C L C E E O S A I SPITALFIELDS I IT A A W B N H D L E W STE S R PNEY WAY T O J R U SALESFORCE A E HOLBORN B T D REE TOWER E ST N I D L XFOR E G T O W R E K G ES H ALDGATE I A H E N TE A O M LONDON MET. -

The Visitation of London Begun in 1687. by Jacob Field

Third Series Vol. II part 1. ISSN 0010-003X No. 211 Price £12.00 Spring 2006 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume II 2006 Part 1 Number 211 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor † John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, B.A., F.S.A., F.H.S. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam GENTRY AT THE CENTRE Jacob Field The Visitation of London begun in 1687, edd. T. C. Wales and C. P. Hartley. Harleian Society publications new series, 16-17 (2003-4). 2 vols. London: The Harleian Society, 2005. The 1687 visitation of London was the last held in England and Wales. It has recent• ly been published in two parts by the Harleian Society, edited by Tim Wales and Carol Hartley. London was easily the largest city in the nation, and the centre of pol• itics, culture and economy.1 As such, the 1687 visitation of London holds a dual his• torical importance as both the last visitation in English history, but also an account of the gentry who inhabited England's wealthiest and most important centre of pop• ulation.2 The edition draws on the visitation pedigrees, as well as various other ancil• lary sources, including two notebooks; one from the College of Arms, and one from the Guildhall.3 Henry VIII inaugurated the system of visitations in 1530, making two senior heralds, Clarenceux and Norroy Kings of Arms, responsible for making periodic vis• its to the counties to ensure all arms were borne with proper authority. -

ESTLIN, Mayor RESOLVED: That the Court of Common Council Holden In

ESTLIN, Mayor RESOLVED: That the Court of Common Council holden in the Guildhall of the City of London on Thursday 25th April 2019, doth hereby appoint the following Committee until the first meeting of the Court in April, 2020. CULTURE, HERITAGE & LIBRARIES COMMITTEE 1. Constitution A Ward Committee consisting of, two Aldermen nominated by the Court of Aldermen up to 31 Commoners representing each Ward (two representatives for the Wards with six or more Members regardless of whether the Ward has sides) or Side of Ward the Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Guildhall School of Music & Drama (ex-officio) the Chairman of the Barbican Centre Board (ex-officio) 2. Quorum The quorum consists of any nine Members. 3. Membership 2019/20 ALDERMEN 1 Robert Picton Seymour Howard 1 Alistair John Naisbitt King COMMONERS 9 Barbara Patricia Newman, C.B.E………...…………………………………………………… Aldersgate 7 Jeremy Paul Mayhew……………..…….……………………………………………………… Aldersgate 9 Sylvia Doreen Moys……….……………………………………………………………………. Aldgate 5 Graeme George Harrower……………………………………………………………………... Bassishaw 2 John Petrie.……………………………….………………………………………………..……. Billingsgate 6 Wendy Hyde, Deputy…………………………..………………………………………………. Bishopsgate 3 Andrew Paul Mayer……………………………………..……………………………………… Bishopsgate 7 Dr Giles Robert Evelyn Shilson, Deputy……………………………………………………… Bread Street 4 John Alfred Bennett, M.B.E., Deputy………………………………………………………… Broad Street (Candlewick has paired with Walbrook for this appointment)....……….……………….…. Candlewick 7 Graham David Packham…………………………………………………………………….….