Fletcher2020.Pdf (4.608Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L O C a L P L

Cairngorms National Park Authority L O C A L P L A N CONSULTATION REPORT: PHASE 1; September - December 2004 (Community consultation prior to Preliminary Draft) March 2005 1 Contents: Page No. 1 Aims of the Park/contacts 2 Introduction 3 Record of Community Meetings 4 Area Demographics 6 Community Co-ordinator’s Reports 7 Summary of Issues 13 Community Meetings; brief summaries 14 Questionnaire; Summary of main results 16 Introduction to Questionnaire & Meeting Results 17 Community Area Results Angus Glens: questionnaire 18 meeting results 21 Aviemore: questionnaire 26 meeting results 43 Ballater & Crathie: questionnaire 47 meeting results 64 Boat of Garten: questionnaire 68 meeting results 80 Braemar + Inverey: questionnaire 85 meeting results 96 Carr-Bridge: questionnaire 99 meeting results 110 Cromdale: questionnaire 116 meeting results 125 Dalwhinnie: questionnaire 127 meeting results 131 Donside: questionnaire 133 meeting results 144 Dulnain Bridge: questionnaire 147 meeting results 157 Glenlivet: questionnaire 159 meeting results 167 Grantown-on-Spey: questionnaire 178 meeting results 195 Kincraig: questionnaire 200 meeting results 213 Kingussie: questionnaire 229 meeting results 243 Laggan: questionnaire 245 meeting results 254 Mid-Deeside + Cromar: questionnaire 256 meeting results 262 Nethy Bridge: questionnaire 267 meeting results 280 Newtonmore: questionnaire 283 meeting results 300 Rothiemurchus + Glenmore: questionnaire 303 meeting results 314 Tomintoul: questionnaire 316 meeting results 327 2 Central to the Cairngorms National Park Local Plan will be the four Aims of the Park: a) to conserve and enhance the natural and cultural heritage of the area; b) to promote sustainable use of the natural resources of the area; c) to promote understanding and enjoyment (including enjoyment in the form of recreation) of the special qualities of the area by the public; and d) to promote sustainable economic and social development of the area’s communities. -

A History of the Lairds of Grant and Earls of Seafield

t5^ %• THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY GAROWNE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD. THE RULERS OF STRATHSPEY A HISTORY OF THE LAIRDS OF GRANT AND EARLS OF SEAFIELD BY THE EARL OF CASSILLIS " seasamh gu damgean" Fnbemess THB NORTHERN COUNTIES NEWSPAPER AND PRINTING AND PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIMITED 1911 M csm nil TO CAROLINE, COUNTESS OF SEAFIELD, WHO HAS SO LONG AND SO ABLY RULED STRATHSPEY, AND WHO HAS SYMPATHISED SO MUCH IN THE PRODUCTION OP THIS HISTORY, THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED BY THE AUTHOR. PREFACE The material for " The Rulers of Strathspey" was originally collected by the Author for the article on Ogilvie-Grant, Earl of Seafield, in The Scots Peerage, edited by Sir James Balfour Paul, Lord Lyon King of Arms. A great deal of the information collected had to be omitted OAving to lack of space. It was thought desirable to publish it in book form, especially as the need of a Genealogical History of the Clan Grant had long been felt. It is true that a most valuable work, " The Chiefs of Grant," by Sir William Fraser, LL.D., was privately printed in 1883, on too large a scale, however, to be readily accessible. The impression, moreover, was limited to 150 copies. This book is therefore published at a moderate price, so that it may be within reach of all the members of the Clan Grant, and of all who are interested in the records of a race which has left its mark on Scottish history and the history of the Highlands. The Chiefs of the Clan, the Lairds of Grant, who succeeded to the Earldom of Seafield and to the extensive lands of the Ogilvies, Earls of Findlater and Seafield, form the main subject of this work. -

Things to Do Around Loch Ness (In No Particular Order!)

Our Top 20 things to do around Loch Ness (in no particular order!) Ness Islands Walk – A walk around the river Ness, and through the smaller islands, connected by a series of bridges. Start the walk from the City Centre, taking in buildings such as the Cathedral and Eden Court on the way, or start on the Dores side of Inverness at the war memorial. The walk can be as long or as short as you want. FREE Inverness Museum and Art Gallery- learn about Scottish geology. Nature and culture, then walk up to and around the castle to enjoy views of the City. FREE Jacobite Cruises - Drive round to the other side of the loch, and get on a Jacobite boat at the Clansman Harbour for a relaxing sail down to Urquhart Castle and back. £13 - £30 Dolphin spotting at Chanonry Point – Between Fortrose and Rosemarkie on the Black Isle, Channonry Point is one of the best spots in the UK to view bottlenose dolphins. They can be seen year-round, but most sightings are in the summer months, and they are best seen at an incoming tide. Chanonry Point is situated East of Fortrose off the A832 FREE Change House Walk - A gentle walk along the shore at the Change House, then follow the marked trail across the road and complete the loop through the woods. FREE Falls of Foyers – A few miles beyond the Change House, you will find one of the must-see sights of south Loch Ness. Starting at the top, with parking beside the shop and café, you can choose to just walk to the first viewpoint for a look, or complete the whole 4.5km loop. -

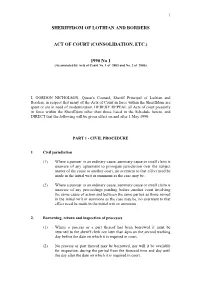

SHERIFFDOM of LOTHIAN and BORDERS Act of Court (Consolidation, Etc.) 1990, No

1 SHERIFFDOM OF LOTHIAN AND BORDERS ACT OF COURT (CONSOLIDATION, ETC.) 1990 No 1 (As amended by Acts of Court No. 1 of 2003 and No. 2 of 2005) I, GORDON NICHOLSON, Queen's Counsel, Sheriff Principal of Lothian and Borders, in respect that many of the Acts of Court in force within the Sheriffdom are spent or are in need of modernisation, HEREBY REPEAL all Acts of court presently in force within the Sheriffdom other than those listed in the Schedule hereto, and DIRECT that the following will be given effect on and after 1 May 1990: PART 1 - CIVIL PROCEDURE 1 Civil jurisdiction (1) Where a pursuer in an ordinary cause, summary cause or small claim is unaware of any agreement to prorogate jurisdiction over the subject matter of the cause to another court, no averment to that effect need be made in the initial writ or summons as the case may be. (2) Where a pursuer in an ordinary cause, summary cause or small claim is unaware of any proceedings pending before another court involving the same cause of action and between the same parties as those named in the initial writ or summons as the case may be, no averment to that effect need be made in the initial writ or summons. 2. Borrowing, return and inspection of processes (1) Where a process or a part thereof has been borrowed it must be returned to the sheriff clerk not later than 4pm on the second working day before the date on which it is required in court. -

The Scottish Nebraskan Newsletter of the Prairie Scots

The Scottish Nebraskan Newsletter of the Prairie Scots Chief’s Message Summer 2021 Issue I am delighted that summer is upon us finally! For a while there I thought winter was making a comeback. I hope this finds you all well and excited to get back to a more normal lifestyle. We are excited as we will finally get to meet in person for our Annual Meeting and Gathering of the Clans in August and hope you all make an effort to come. We haven't seen you all in over a year and a half and we are looking forward to your smiling faces and a chance to talk with all of you. Covid-19 has been rough on all of us; it has been a horrible year plus. But the officers of the Society have been meeting on a regular basis trying hard to keep the Society going. Now it is your turn to come and get involved once again. After all, a Society is not a society if we don't gather! Make sure to mark your calendar for August 7th, put on your best Tartan and we will see you then. As Aye, Helen Jacobsen Gathering of the Clans :an occasion when a large group of family or friends meet, especially to enjoy themselves e.g., Highland Games. See page 5 for info about our Annual Meeting & Gathering of the Clans See page 15 for a listing of some nearby Gatherings Click here for Billy Raymond’s song “The Gathering of the Clans” To remove your name from our mailing list, The Scottish Society of Nebraska please reply with “UNSUBSCRIBE” in the subject line. -

Clan Grant Magazine Issue MK55

Standfast - Spring/Summer 2020 - Issue MK55 Spring/Summer 2020 5 Standfast –- Spring/SummerAutumn/Winter 2020 2019 -– Issue Issue MK MK5455 SOCIETY COUNCIL MEMBERS Patron Chairman Vice Chairman The Rt. Hon Sir James Grant of Fiona Grant, Don Grant, Grant, Monymusk, Milton Keynes, Lord Strathspey, Aberdeenshire Buckinghamshire Baronet of Nova Scotia, tel: 01467 651333 33rd Chief of Clan Grant, fiona@ monymusk.com Duthil, Inverness-shire Treasurer Membership Secretary Standfast Editor Andrew G Grant, Kim Todd, Monymusk, Sir Archibald Grant, Belper, Derbyshire Aberdeenshire Monymusk, Aberdeenshire Stand Organiser Tent Organiser Parade Marshal Olga Grant, Judy Lewis, Tim Atkinson, Daviot, Inverness-shire Duthil, Inverness-shire Factor at Ben Alder Estate, Dalwhinnie 2 Standfast -– Spring/Summer Autumn/Winter 2020 2019 -– Issue Issue MK MK5455 CONTENTS In this edition of Standfast… Front Cover: DavidThe Chief, E Grant Standard with his Bearers, daughter Chieftains Susannah -and celebrating Clan Marching his 80th Birthdayto the Nethy at the Abernethy Games,Bridge pictured Games outside the Clan Grant tent. Back Cover: Piper to the Laird of Grant’ ‘Image © National Museums Scotland’ Inside back cover; The ‘Champion to the Laird of Grant’ © Reidhaven Trust (Courtesy of GrantownRegulars Museum) Features 2. Society Council Members 6. Way in to Instagram Page 3.Regulars Message from the Chief Features 2. Society Council Members 12. Battle of Glenshiel Commemoration Ceremony 4. Letter from the Chairman 3. Message from the Chief 13. Archeological Treasures found at Glenshiel – P&J 4. Letter from the Chairman 14. A Galaxy of Grants at the Gathering, by David E Grant 5. Notes from the Vice Chairman 17. International Gathering 2020 – Updated Draft Programme Message6. -

Giving Evidence in Court

Giving Evidence in Court South Lanarkshire Child Protection Committee A Practical Guide to Getting it Right SLCPC Multi-Agency Court Skills Guidance for Professionals (2020) www.childprotectionsouthlanarkshire.org.uk Review Date: December 2022 INFORMATION ABOUT GOING TO COURT A useful multi-agency guide for professionals working in the field of Child Protection. Please always refer to single agency guidance on this topic in the first instance. GETTING A CITATION KNOW WHY YOU ARE GIVING EVIDENCE AND FOR WHOM In both civil and criminal proceedings, any of the involved parties (i.e. pursuer, defender, Procurator Fiscal, the accused person’s defence counsel, Authority Reporter) can call witnesses. You may even be called to give evidence by the side opposing your views. You will receive a court citation, which is the summons sent to witnesses obligating them to appear in court. Please note it is not acceptable, thereafter to book holidays / days off. If you are aware that you may be called to give evidence in any forthcoming proceedings, it is worth notifying the relevant people of any annual leave you have booked. Be aware that you can be asked to attend court if you are on leave but not abroad. PREPARE FOR PRECOGNITION Opposing sides (criminal / civil) can interview each other’s witnesses prior to attendance in Court, with the purpose of establishing the evidence witnesses are likely to give in Court. This is called precognition. Precognition agent or officer acting on behalf of any ‘side’ will arrange to take a statement. Precognition statements are not admissible as evidence and you can’t be cross-examined on them. -

Scotland Practical Conservation

Residential Volunteer Internship placement information: Central Highland Reserves, North Scotland Practical Conservation Overall purpose of the role A fantastic opportunity to spend up to 12 months on 5 different reserves to gain experience and develop your skills and knowledge with the aim of achieving employment in the conservation sector. You will be an essential and integral part of the Central Highland Reserves team with responsibility for aspects of the reserves management and individual projects. You will be involved with practical conservation, working with volunteers, health & safety, surveys and office based tasks. The Central Highland Reserves team is based at the North Scotland Regional Office which provides opportunities to network with a wide range of staff from a range of disciplines. The reserves are located around the Moray coast including Nigg & Udale Bays, Fairy Glen, Loch Ruthven and Culbin Sands. In this role you will gain: “This position has • Experience of working as part of a small reserves team. hugely improved my CV • Certified training relevant to the role worth approx. £1500 including and the additional help First Aid, brushcutter, 4x4 off road driving, Safe use of Pesticides (PA1 to find jobs and & PA6). opportunities has been • Experience of working on a range of habitats greatly appreciated. I’ve • Survey and monitoring which may include Slavonian grebe, black seen some of the best grouse and waders. wildlife that the • Opportunities to work with other reserves in the North Scotland Region Highlands has to offer, • Experience of working with and leading volunteers from beautifully bright • Skills in prioritizing, time management, problems solving and planning. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

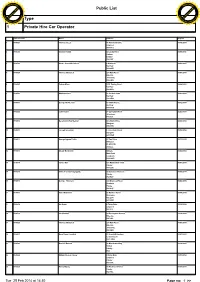

Public List Type 1 Private Hire Car Operator

Ch F-X ang PD e Public List w w m w Click to buy NOW! o . .c tr e Type ac ar ker-softw 1 Private Hire Car Operator Reference No. Name Address Expires 1 PH0501 Thomas Steen 11 Richmond Drive 31/10/2014 Linwood PA3 3TQ 2 PH0502 Stephen Smith 42 Lochy Place 31/08/2015 Linburn Erskine PA8 6AY 3 PH0503 Stuart James McCulloch 4 Kirklands 28/02/2015 Renfrew PA4 8HR 4 PH0504 Thomas McGarrell 287 Main Road 31/03/2014 Elderslie Johnstone PA5 9ED 5 PH0505 Farhan Khan 135F Paisley Road 30/09/2014 Renfrew PA4 8XA 6 PH0506 Matthew Kane 26 Cockels Loan 30/09/2014 Renfrew PA4 0RG 7 PH0507 George McPherson 40 Third Avenue 31/12/2014 Renfrew PA4 OPX 8 PH0508 John Deans 37 Springfield Park 30/06/2014 Johnstone PA5 8JS 9 PH0510 Derek John Hay Stewart 22 Lintlaw Drive 28/02/2014 Glasgow G52 2NS 10 PH0511 Joseph Sebastian 5 Crosstobs Road 30/09/2014 Glasgow G53 5SW 11 PH0512 George Ingram Dickie 44 Yair Drive 31/12/2015 Hillington GLASGOW G52 2LE 12 PH0513 Alistair Borthw ick Kilblane 30/04/2014 Main Road Langbank PA14 6XP 13 PH0514 James Muir 10c Maxwellton Court 30/06/2014 Paisley PA1 2UE 14 PH0515 Shibu Thomas Payyappilly 28 Denewood Avenue 31/03/2014 Paisley PA2 8DY 15 PH0516 George Thomson 222 Braehead Road 30/04/2015 Glenburn Paisley PA2 8QF 16 PH0517 Alan McDonald 21 Murroes Road 31/08/2014 Drumoyne Glasgow G51 4NR 17 PH0518 Ian Grant 4 Finlay Drive 30/09/2014 Linwood PA3 3LJ 18 PH0519 Iain Waddell 64 Dunvegean Avenue 31/10/2014 Elderslie PA5 9NL 19 PH0520 Thomas McGarrell 287 Main Road 31/08/2014 Elderslie Johnstone PA5 9ED 20 PH0521 Hazel Jane Crawford 64 Crookhill Gardens 31/01/2014 Lochwinnoch PA12 4BA 21 PH0522 David O'Donnell 32 Glendower Way 31/10/2015 Foxbar Paisley PA2 22 PH0524 William Steven Calvey 2 Irvine Drive 31/03/2014 Linwood Paisley PA3 3TA 23 PH0525 Henry Mejury 33 Birchwood Drive 31/03/2014 Paisley PA2 9NE Tue 25 Feb 2014 at 14:30 Page no: 1 >> Ch F-X ang PD e Reference No. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

The Dalradian Rocks of the North-East Grampian Highlands of Scotland

Revised Manuscript 8/7/12 Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 The Dalradian rocks of the north-east Grampian 6 7 Highlands of Scotland 8 9 D. Stephenson, J.R. Mendum, D.J. Fettes, C.G. Smith, D. Gould, 10 11 P.W.G. Tanner and R.A. Smith 12 13 * David Stephenson British Geological Survey, Murchison House, 14 West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 15 [email protected] 16 0131 650 0323 17 John R. Mendum British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 18 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 19 Douglas J. Fettes British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 20 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 21 C. Graham Smith Border Geo-Science, 1 Caplaw Way, Penicuik, 22 Midlothian EH26 9JE; formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 23 David Gould formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 24 P.W. Geoff Tanner Department of Geographical and Earth Sciences, 25 University of Glasgow, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow 26 27 G12 8QQ. 28 Richard A. Smith formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 29 30 * Corresponding author 31 32 Keywords: 33 Geological Conservation Review 34 North-east Grampian Highlands 35 Dalradian Supergroup 36 Lithostratigraphy 37 Structural geology 38 Metamorphism 39 40 41 ABSTRACT 42 43 The North-east Grampian Highlands, as described here, are bounded 44 to the north-west by the Grampian Group outcrop of the Northern 45 Grampian Highlands and to the south by the Southern Highland Group 46 outcrop in the Highland Border region. The Dalradian succession 47 therefore encompasses the whole of the Appin and Argyll groups, but 48 also includes an extensive outlier of Southern Highland Group 49 strata in the north of the region.