4.3 Gulf War, 1991

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Southern Iraq Herpetofauna

Vol. 3 (1): 61-71, 2019 A Review of Southern Iraq Herpetofauna Nadir A. Salman Mazaya University College, Dhi Qar, Iraq *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: The present review discussed the species diversity of herpetofauna in southern Iraq due to their scientific and national interests. The review includes a historical record for the herpetofaunal studies in Iraq since the earlier investigations of the 1920s and 1950s along with the more recent taxonomic trials in the following years. It appeared that, little is known about Iraqi herpetofauna, and no comprehensive checklist has been done for these species. So far, 96 species of reptiles and amphibians have been recorded from Iraq, but only a relatively small proportion of them occur in the southern marshes. The marshes act as key habitat for globally endangered species and as a potential for as yet unexplored amphibian and reptile diversity. Despite the lack of precise localities, the tree frog Hyla savignyi, the marsh frog Pelophylax ridibunda and the green toad Bufo viridis are found in the marshes. Common reptiles in the marshes include the Caspian terrapin (Clemmys caspia), the soft-shell turtle (Trionyx euphraticus), the Euphrates softshell turtle (Rafetus euphraticus), geckos of the genus Hemidactylus, two species of skinks (Trachylepis aurata and Mabuya vittata) and a variety of snakes of the genus Coluber, the spotted sand boa (Eryx jaculus), tessellated water snake (Natrix tessellata) and Gray's desert racer (Coluber ventromaculatus). More recently, a new record for the keeled gecko, Cyrtopodion scabrum and the saw-scaled viper (Echis carinatus sochureki) was reported. The IUCN Red List includes six terrestrial and six aquatic amphibian species. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Possibilities of Restoring the Iraqi Marshes Known As the Garden of Eden

Water and Climate Change in the MENA-Region Adaptation, Mitigation,and Best Practices International Conference April 28-29, 2011 in Berlin, Germany POSSIBILITIES OF RESTORING THE IRAQI MARSHES KNOWN AS THE GARDEN OF EDEN N. Al-Ansari and S. Knutsson Dept. Civil, Mining and Environmental Engineering, Lulea University, Sweden Abstract The Iraqi marsh lands, which are known as the Garden of Eden, cover an area about 15000- 20000 sq. km in the lower part of the Mesopotamian basin where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers flow. The marshes lie on a gently sloping plan which causes the two rivers to meander and split in branches forming the marshes and lakes. The marshes had developed after series of transgression and regression of the Gulf sea water. The marshes lie on the thick fluvial sediments carried by the rivers in the area. The area had played a prominent part in the history of man kind and was inhabited since the dawn of civilization by the Summarian more than 6000 BP. The area was considered among the largest wetlands in the world and the greatest in west Asia where it supports a diverse range of flora and fauna and human population of more than 500000 persons and is a major stopping point for migratory birds. The area was inhabited since the dawn of civilization by the Sumerians about 6000 years BP. It had been estimated that 60% of the fish consumed in Iraq comes from the marshes. In addition oil reserves had been discovered in and near the marshlands. The climate of the area is considered continental to subtropical. -

Powpa Action-Plan-Republic of Iraq

Action Plan for Implementing the Programme of Work on Protected Areas of the Convention on Biological Diversity Iraq Submitted to the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity [20 May 2012] Protected area information: PoWPA Focal Point Dr. Ali Al-Lami, Ph.D.(Ecologist) Minister Advisor; Ministry of Environment of Iraq Email: [email protected] Lead implementing agency : Ministry of Environment of Iraq Multi-stakeholder committee : In Iraq there are several national Committees that were established to support the Government in developing policies, planning and reporting on different environmental fields. As for Protected areas, two national committees are relevant: - The National Committee for Protected Areas - Iraq National Marshes and Wetlands Committee National Committee for Protected Areas A National Committee for Protected Areas was established in 2008 for planning and management of a network of Protected Areas in Iraq. This national inter-ministerial Committee is lead by the Ministry of Environment and is formed by the representatives of the following institutions: • Ministry of Environment (Leader) • Ministry of Higher Education & Scientific Research • Ministry of Water Resources • Ministry of Science & Technology • Ministry of Municipalities & Public Works • Ministry of State for Tourism & Antiquities • Ministry of Agriculture • Ministry of Education • NGO representative Nature Iraq Organization Iraq National Marshes and Wetlands Committee (RAMSAR Convention) The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands was ratified by Iraq in October -

505 the Lost Language of Ancient

MEDICINA NEI SECOLI ARTE E SCIENZA, 30/2 (2018) 505-530 Journal of History of Medicine Articoli/Articles THE LOST LANGUAGE OF ANCIENT BABYLONIAN PLANTS: FROM MYTH TO MEDICINE BARBARA BÖCK Instituto de Lenguas y Culturas del Mediterráneo y Oriente Próximo Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Madrid, ES SUMMARY The Sumerian myth of Enki and Ninḫursaga, which conveys Enki’s metaphorical nature as power behind the irrigation of the Mesopotamian marshlands, contains a passage that brings together plants, pains and deities. The raison d’être for the choice of these eight plants has so far escaped scholars. In analysing the evidence for the plants according to cuneiform literary and medical sources the present contribution offers a discussion of their nature and possible connection with the god Enki providing thus an explanation for their choice and shedding light on the storyteller’s motivation for including the episode on plants in the myth. Although Ancient Babylonians did not produce mythological nar- rations or other literary traditions about plants comparable to the Classical world, references to the plant kingdom indeed entered the cuneiform belles-lettres. A rather bizarre passage that brings togeth- er plants, pains and deities and which will be discussed in the present contribution is included in the Sumerian myth about the god of wis- dom and sweet waters, Enki, and Ninhursag, a mother goddess. The narration is also known as “Sumerian Epic of Paradise” as coined by its first editor Stephen Langdon in 19151. The Sumerologist S.N. Kramer observed that it “is one of the more interesting, intricate, Key words: Enki and Ninḫursaga - Enki and Fishes - Aquatic Plants - Medicine and Myth 505 Barbara Böck and imaginative myths in the Sumerian repertoire, but also one of the most enigmatic and frustrating”2. -

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE and HERITAGE Basra Its History, Culture and Heritage

BASRA : ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE CULTURE : ITS HISTORY, BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins Edited by Paul Collins BASRA ITS HISTORY, CULTURE AND HERITAGE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE CELEBRATING THE OPENING OF THE BASRAH MUSEUM, SEPTEMBER 28–29, 2016 Edited by Paul Collins © BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 2019 ISBN 978-0-903472-36-4 Typeset and printed in the United Kingdom by Henry Ling Limited, at the Dorset Press, Dorchester, DT1 1HD CONTENTS Figures...................................................................................................................................v Contributors ........................................................................................................................vii Introduction ELEANOR ROBSON .......................................................................................................1 The Mesopotamian Marshlands (Al-Ahwār) in the Past and Today FRANCO D’AGOSTINO AND LICIA ROMANO ...................................................................7 From Basra to Cambridge and Back NAWRAST SABAH AND KELCY DAVENPORT ..................................................................13 A Reserve of Freedom: Remarks on the Time Visualisation for the Historical Maps ALEXEI JANKOWSKI ...................................................................................................19 The Pallakottas Canal, the Sealand, and Alexander STEPHANIE -

Chemical Weapons and the Iran-Iraq War a Discussion of the UN Security Council’S Response to the Use of Gas in the Iran-Iraq War 1980-1988

Chemical Weapons and the Iran-Iraq War A discussion of the UN Security Council’s response to the use of gas in the Iran-Iraq war 1980-1988 MA Thesis in History Randi Hunshamar Øygarden Department of AHKR Autumn 2014 2 Acknowledgements I am grateful for the help I have received with this thesis. First of all I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Anders Bjørkelo. He has given me thorough feedback, advices and provided me with new perspectives when I have been lost in my work. I would also like to thank Professor Knut S. Vikør and Dr. Anne K. Bang at the University of Bergen. They have both given me useful inputs and feedback on drafts I have presented at the weekly seminars in Middle Eastern History. I am also very grateful to the staff at the library at the Nobel Peace Prize Institute in Oslo, who has been very helpful in finding primary sources. I would also like to thank Evy Ølberg and Kristine Moe, who have taken their time to proofread and to give comments on the content and structure of the thesis. This MA thesis marks the end of my studies and I would like to thank my parents for not only supporting me in my MA work, but throughout all my years of study at the university. Last, but not least, I would like to thank my boyfriend Mattias for motivation, encouragement and IT-support 24/7. Randi Hunshamar Øygarden Bergen, 20.11.2014 3 4 Table of Content Acknowledgements 3 1. Introduction 7 Research Questions 8 Hypotheses 9 Historiography, sources and methods 11 2. -

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management in the Iraqi Marshlands

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management in the Iraqi Marshlands Screening Study on Potential World Heritage Nomination Tobias Garstecki and Zuhair Amr IUCN REGIONAL OFFICE FOR WEST ASIA 1 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN. Published by: IUCN ROWA, Jordan Copyright: © 2011 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Garstecki, T. and Amr Z. (2011). Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management in the Iraqi Marshlands – Screening Study on Potential World Heritage Nomination. Amman, Jordan: IUCN. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1353-3 Design by: Tobias Garstecki Available from: IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Regional Office for West Asia (ROWA) Um Uthaina, Tohama Str. No. 6 P.O. Box 942230 Amman 11194 Jordan Tel +962 6 5546912/3/4 Fax +962 6 5546915 [email protected] www.iucn.org/westasia 2 Table of Contents 1 Executive -

The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities

Third State of Conservation Report Addressed by the Republic of Iraq to the World Heritage Committee on The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities World Heritage Property n. 1481 November 2020 1 Table of Contents 1. Requests by the World Heritage Committee 2. Cultural heritage 3. Natural heritage 4. Integrated management plan 5. Tourism plan 6. Engaging local communities in matters related to water use 7. World heritage centre/icomos/iucn reactive monitoring mission to the property 8. Planed construction projects 9. Survey the birds of prey coming in the marshes 10. Signature of the concerned authority 11. Annexes 2 1- REQUESTS BY THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE This report addresses the following requests expressed by World Heritage Committee in its Decision 43 COM 7B.35 (paragraphs 119 – 120), namely: 3. Welcomes the start of conservation work by international archaeological missions at the three cultural components of the property, Ur, Tell Eridu and Uruk, and, the comprehensive survey undertaken at Tell Eridu; 4. Regrets that no progress has been reported on the development of site-specific conservation plans for the three cultural components of the property, as requested by the Committee in response to the significant threats they face related to instability, significant weathering, inappropriate previous interventions, and the lack of continuous maintenance; 5. Urges the State Party to extend the comprehensive survey and mapping to all three cultural components of the property, as baseline data for future work, and to develop operational conservation plans for each as a matter of priority, and to submit these to the World Heritage Centre for review by the Advisory Bodies; 6. -

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

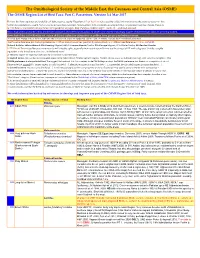

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

Consolidated Management Plan of the Ahwar of Southern Iraq

Consolidated Management Plan of The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities Property Nominated by the Government of Iraq in January 2014 for Inscription on the World Heritage List This document was developed by Khaled Allam Harhash, Geraldine Chatelard, Sami el-Masri and Gaetano Palumbo assisted by Qahtan Al Abeed, Hussein Al Assadi, Salim Khalaf Anid, Ayad Kadhum Dawood, Ali Kadhem Ghanem, Ahmad Hanun, Mudhafar Salim, and Ali Ubaid Shalgham. The management plan preparation was led by IUCN-ROWA and ARC-WH in the framework of the UNEP-UNESCO joint initiative “World Heritage inscription process as a tool to enhance the natural and cultural management of the Iraqi Marshlands.” This multiphase capacity-building project was managed by UNEP-DTIE-IETC and subsequently UNEP-ROWA, in collaboration with UNESCO Iraq Office, and received generous funding from the Governments of Japan and Italy. This Consolidated Management Plan completes the basic Management Planning Frameworks for the natural and cultural components of the property submitted to the World Heritage Centre in January 2014 with the nomination dossier of The Ahwar of Southern Iraq: Refuge of Biodiversity and Relict Landscape of the Mesopotamian Cities. A substantial consultation process was conducted to insure that the provisions of this Consolidated Management Plan are issued from and shared with the concerned stakeholders. Gratitude is conveyed to Diane Klaimi at UNEP-ROWA, Fadi Shraideh and Hany El-Shaer at IUCN-ROWA, together with Mounir Bouchenaki, Khalifa Al Khalifa, Kamal Bitar and Haifaa Abdulhalim at ARC-WH for their administrative and/or technical support during the management plan preparation phase. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION.