Mitteleuropa Blues, Perilous Remedies: Andrzej Stasiuk's Harsh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dušan Šarotar, Born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, Is a Writer, Poet and Screenwri- [email protected] Ter

Foreign Rights Beletrina Academic Press About the Author (Študentska založba) Renata Zamida Borštnikov trg 2 SI-1000 Ljubljana Dušan Šarotar, born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, is a writer, poet and screenwri- [email protected] ter. He studied Sociology of Culture and www.zalozba.org Philosophy at the University of Ljublja- www.readcentral.org na. He has published two novels (Island of the Dead in 1999 and Billiards at the Translation: Gregor Timothy Čeh Dušan Šarotar Hotel Dobray in 2007), three collecti- ons of short stories (Blind Spot, 2002, Editor: Renata Zamida Author’s Catalogue Layout: designstein.si Bed and Breakfast, 2003 and Nostalgia, Photo: Jože Suhadolnik, Dušan Šarotar 2010) and three poetry collections (Feel Proof-reading: Catherine Fowler, for the Wind, 2004, Landscape in Minor, Marianne Cahill 2006 and The House of My Son, 2009). Ša- rotar also writes puppet theatre plays Published by Beletrina Academic Press© and is author of fifteen screenplays for Ljubljana, 2012 documentary and feature films, mostly for television. The author’s poetry and This publication was published with prose have been included into several support of the Slovene Book Agency: anthologies and translated into Hunga- rian, Russian, Spanish, Polish, Italian, Czech and English. In 2008, the novel Billiards at the Hotel Dobray was nomi- nated for the national Novel of the Year Award. There will be a feature film ba- ISBN 978-961-242-471-8 sed on this novel filmed in 2013. Foreign Rights Beletrina Academic Press About the Author (Študentska založba) Renata Zamida Borštnikov trg 2 SI-1000 Ljubljana Dušan Šarotar, born in Murska Sobota +386 1 200 37 07 in 1968, is a writer, poet and screenwri- [email protected] ter. -

Fall 2011 / Winter 2012 Dalkey Archive Press

FALL 2011 / WINTER 2012 DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS CHAMPAIGN - LONDON - DUBLIN RECIPIENT OF THE 2010 SANDROF LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT Award FROM THE NatiONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE what’s inside . 5 The Truth about Marie, Jean-Philippe Toussaint 6 The Splendor of Portugal, António Lobo Antunes 7 Barley Patch, Gerald Murnane 8 The Faster I Walk, the Smaller I Am, Kjersti A. Skomsvold 9 The No World Concerto, A. G. Porta 10 Dukla, Andrzej Stasiuk 11 Joseph Walser’s Machine, Gonçalo M. Tavares Perfect Lives, Robert Ashley (New Foreword by Kyle Gann) 12 Best European Fiction 2012, Aleksandar Hemon, series ed. (Preface by Nicole Krauss) 13 Isle of the Dead, Gerhard Meier (Afterword by Burton Pike) 14 Minuet for Guitar, Vitomil Zupan The Galley Slave, Drago Jančar 15 Invitation to a Voyage, François Emmanuel Assisted Living, Nikanor Teratologen (Afterword by Stig Sæterbakken) 16 The Recognitions, William Gaddis (Introduction by William H. Gass) J R, William Gaddis (New Introduction by Robert Coover) 17 Fire the Bastards!, Jack Green 18 The Book of Emotions, João Almino 19 Mathématique:, Jacques Roubaud 20 Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, Aglaja Veteranyi (Afterword by Vincent Kling) 21 Iranian Writers Uncensored: Freedom, Democracy, and the Word in Contemporary Iran, Shiva Rahbaran Critical Dictionary of Mexican Literature (1955–2010), Christopher Domínguez Michael 22 Autoportrait, Edouard Levé 23 4:56: Poems, Carlos Fuentes Lemus (Afterword by Juan Goytisolo) 24 The Review of Contemporary Fiction: The Failure Issue, Joshua Cohen, guest ed. Available Again 25 The Family of Pascual Duarte, Camilo José Cela 26 On Elegance While Sleeping, Viscount Lascano Tegui 27 The Other City, Michal Ajvaz National Literature Series 28 Hebrew Literature Series 29 Slovenian Literature Series 30 Distribution and Sales Contact Information JEAN-PHILIPPE TOUSSAINT titles available from Dalkey Archive Press “Right now I am teaching my students a book called The Bathroom by the Belgian experimentalist Jean-Philippe Toussaint—at least I used to think he was an experimentalist. -

The Central Europe of Yuri Andrukhovych and Andrzej Stasiuk

Rewriting Europe: The Central Europe of Yuri Andrukhovych and Andrzej Stasiuk Ariko Kato Introduction When it joined the European Union in 2004, Poland’s eastern bor- der, which it shared with Ukraine and Belarus, became the easternmost border of the EU. In 2007, Poland was admitted to the Schengen Con- vention. The Polish border then became the line that effectively divided the EU identified with Europe from the “others” of Europe. In 2000, on the eve of the eastern expansion of the EU, Polish writer Andrzej Stasiuk (1960) and Ukrainian writer Yuri Andrukhovych (1960) co-authored a book titled My Europe: Two Essays on So-called Central Europe (Moja Europa: Dwa eseje o Europie zwanej Środkową). The book includes two essays on Central Europe, each written by one of the authors. Unlike Milan Kundera, who discusses Central Europe as “a kidnapped West” which is “situated geographically in the center—cul- turally in the West and politically in the East”1 in his well-known essay “A Kidnapped West, or the Tragedy of Central Europe” (“Un Occident kidnappé ou la tragédie de l’Europe centrale”) (1983),2 written in the Cold War period, they describe Central Europe neither as a corrective concept nor in terms of the binary opposition of West and East. First, as the subtitle of this book suggests, they discuss Central Europe as “my 1 Milan Kundera, “A Kidnapped West or Culture Bows Out,” Granta 11 (1984), p. 96. 2 The essay was originally published in French magazine Le Débat 27 (1983). - 91 - Ariko Kato Europe,” drawing from their individual perspectives. -

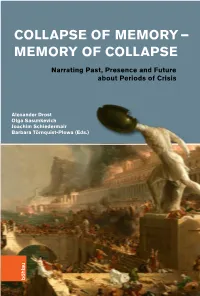

Collapse of Memory

– – COLLAPSE OF MEMORY – MEMORY OF COLLAPSE Narrating Past, Presence and Future about Periods of Crisis Alexander Drost Olga Sasunkevich Joachim Schiedermair COLLAPSE OF MEMORY OF COLLAPSE MEMORY Barbara Törnquist-Plewa (Eds.) Alexander Drost, Volha Olga Sasunkevich, Olga Sasunkevich, Alexander Drost, Volha Joachim Schiedermair, Barbara Törnquist-Plewa Joachim Schiedermair, Barbara Törnquist-Plewa Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Alexander Drost ∙ Olga Sasunkevich Joachim Schiedermair ∙ Barbara Törnquist-Plewa (Ed.) COLLAPSE OF MEMORY – MEMORY OF COLLAPSE NARRATING PAST, PRESENCE AND FUTURE ABOUT PERIODS OF CRISIS BÖHLAU VERLAG WIEN KÖLN WEIMAR Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC 4.0 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft aus Mitteln des Internationalen Graduiertenkollegs 1540 „Baltic Borderlands: Shifting Boundaries of Mind and Culture in the Borderlands of the Baltic Sea Region“ Published with assistance of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft by funding of the International Research Training Group “Baltic Borderlands: Shifting Boundaries of Mind and Culture in the Borderlands of the Baltic Sea Region” Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek : Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie ; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2019 by Böhlau Verlag GmbH & Cie, Lindenstraße 14, D-50674 Köln -

Andrzej Stasiuk and the Literature of Periphery

I got imprisoned for rock and roll. Andrzej Stasiuk and the Literature of Periphery Krzysztof Gajewski Institute of Literary Research Polish Academy of Science Warsaw/New York, 15 April 2021 1 / 64 Table of Contents Andrzej Stasiuk. An Introduction Literature of periphery Forms of periphery in the work of Stasiuk Biographical periphery Social periphery Political periphery Cultural periphery 2 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk. An Introduction 3 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk 4 / 64 USA Poland • la Pologne, c'est-à-dire nulle part (Alfred Jarry, Ubu the King, 1888) • Poland, "that is to say nowhere" 5 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk bio Andrzej Stasiuk born on Sept., 25th, 1960 in Warsaw 6 / 64 Warsaw in the 1960. 7 / 64 Warsaw in the 1960. 8 / 64 Warsaw in the 1960. 9 / 64 Warsaw in the 1960. 10 / 64 Warsaw in the 1960. 11 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk bio attended Professional High School of Car Factory in Warsaw 12 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk bio 1985 anti-communist Freedom and Peace Movement 13 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk literary debut (1989?) 14 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk, Prison is hell These two words in English are one of the most frequ- ently performed tattoos in Polish prisons.1 1Andrzej Stasiuk, Prison is hell, Warsaw 1989? 15 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk bio since 1990 publishing poetry and prose in Po prostu, bruLion, Czas Kultury, Magazyn Literacki, Tygodnik Powszechny and others 16 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk in 1994 Andrzej Stasiuk in 1994: He doesn't have any special beliefs. Smokes a lot 17 / 64 Andrzej Stasiuk bio 1986 left Warsaw and settled in the mountains Low Beskids: Czarne 18 / 64 Low Beskids Czarne 19 / 64 Low Beskids Czarne 20 / 64 Beskid Niski - Czarne St. -

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets. An analysis of authors, languages, and flows. Written by Miha Kovač and Rüdiger Wischenbart, with Jennifer Jursitzky and Sabine Kaldonek, and additional research by Julia Coufal. www.wischenbart.com/DiversityReport2010 Contact: [email protected] 2 Executive Summary The Diversity Report 2010, building on previous research presented in the respective reports of 2008 and 2009, surveys and analyzes 187 mostly European authors of contemporary fiction concerning translations of their works in 14 European languages and book markets. The goal of this study is to develop a more structured, data-based understanding of the patterns and driving forces of the translation markets across Europe. The key questions include the following: What characterizes the writers who succeed particularly well at being picked up by scouts, agents, and publishers for translation? Are patterns recognizable in the writers’ working biographies or their cultural background, the language in which a work is initially written, or the target languages most open for new voices? What forces shape a well-established literary career internationally? What channels and platforms are most helpful, or critical, for starting a path in translation? How do translations spread? The Diversity Report 2010 argues that translated books reflect a broad diversity of authors and styles, languages and career paths. We have confirmed, as a trend with great momentum, that the few authors and books at the very top, in terms of sales and recognition, expand their share of the overall reading markets with remarkable vigor. Not only are the real global stars to be counted on not very many fingers. -

Discourses About Central Europe in Hungarian and Polish Essayism

Discourses About Central Europe in Hungarian and Polish Essayism After 1989 By Andrzej Sadecki Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Balázs Trencsényi Second Reader: Maciej Janowski CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2012 Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The thesis traces the developments in the discourse about Central Europe following the peak of its popularity in the 1980s. First, it overviews the origins and various definitions of the concept. Then, it discusses the 1980s‟ discourse which lays ground for the further analysis. Finally, it examines a selection of essays representative for the post-1989 discourse written by Krzysztof Czyżewski, Péter Esterházy, Aleksander Fiut, Lajos Grendel, Csaba Gy. Kiss, Robert Makłowicz, Andrzej Stasiuk, and László Végel. The analysis is organized around three research questions: how do the authors employ the term of Central Europe, what features they attribute to the region and who do they perceive as significant others of Central Europe. The post-1989 essayism about Central Europe demonstrated several continuities and ruptures in comparison with the discourse of the 1980s. -

Hiking in the Carpathians

Hiking in the Carpathians Detailed Itinerary Poland, Slovakia & Ukraine Nov 26/19 Journey to remote villages and mountains in a classic Facts & Highlights hiking trip, starting in the old Polish capital of Krakow. • 17 land days • Maximum 16 travelers • Start in Krakow, Ancient capitals, rural villages, stunning mountain Poland; Finish in Kiev, Ukraine • All meals included ranges, lakes and rivers, museums, UNESCO churches • Visit medieval Krakow, Lviv Bardejoy (all UNESCO) and Kiev • Encounter friendly villagers & remote wilderness on 7 and monasteries are some of the highlights you will hikes in the remote Carpathian mountains • Find remnants encounter on this 17 day adventure to Poland, Slovakia of the Soviet Era including the architecture, cars and a Soviet and Ukraine. ‘scenic train’ journey. • Visit Chernobyl’s abandoned villages/ cities overgrown with forests, reactor #4 (meltdown site), to One of the highlights of your journey will be the top secret radar sites, the pinnacle of Soviet Spy technology welcoming smiles of villagers as we stop in for lunch at and defence.• Explore Dukla Pass with WWII tanks scattered over rural farms. • Visit Oskar Schindler’s factory • Explore a local home on one of our walks. Our hikes and travels Wieliczka Salt Mines (UNESCO) take us off the beaten path where our local encounters Departure Dates & Price are genuine and spontaneous. Sep 09 - Sep 25, 2020 - $6695 USD We visit Oskar Schindler’s factory, Wieliczka Salt Mines Sep 08 - Sep 24, 2021 - $6695 USD (UNESCO), a Carpathian horse farm, nature parks, Activity Level: 3/4 castles, war memorials, opera house/ballet, schools and Comfort Level: Several long walks. -

ARTICLES PAVEL MACU National Assimilation: the Case of the Rusyn-Ukrainians of Czechoslovakia1 During the Past Century and A

ARTICLES PAVEL MACU National Assimilation: The Case of the Rusyn-Ukrainians of Czechoslovakia1 During the past century and a half various ethnic groups in Eastern Europe have been consolidated into clearly defined nationalities. The intelligentsia has played a crucial role in this process. An ethnic group represents a population which usually possesses a distinct territory, related dialects, and common ethnographic, historical, literary, and religious traditions. However. members of ethnic groups are not necessarily aware of these interrelations and it is the task of the intelligentsia to foster in them a sense of national consciousness. Possession of such a state of mind among a significant portion of a given population allows for the transition from the status of an ethnic group 2 to a nationality." In the initial stages of this consolidation process, there were frequently several choices open to the intelligentsias of Eastern Europe. For instance, in the multinational Austro- Hungarian, German, and Russian empires, a member of a national minority could have identified with the ruling nationality or with the ethnic group into which he was born. Hence, Czechs or Poles might have become Cermanized; Ukrainians or Belorussians Russified; Slovaks, Jews, or Croats Magyarized. For those who did not join the ruling group, there were sometimes other choices: an ethnic Ukrainian in the Austrian province of Galicia could identify himself as a Polc, a Russian, or a Ukrainian, while an ethnic Slovak in northern Hungary might become a Magyar, a Czech, or remain a Slovak. The respective intelligentsias did not operate in an ideological vacuum; their decisions were influenced by the limitations and requirements of contemporary political reality. -

The Usage of the Czechoslovakian Armour and Air Force in the Battle of the Dukla Pass of 1944

The usage of the Czechoslovakian armour and air force in the Battle of the Dukla Pass of 1944 The aim of this dissertation is to illustrate how the usage of the Czechoslovakian armour and air force influenced the course of the Battle of the Dukla Pass of 1944. The Author tried to outline the combat operations of the above mentioned units of the First Czechoslovak Army Corps fighting alongside the 38th Army. The author was induced to undertake the subject due to the fact that the presented battles took place in the South-East of today’s Poland as well as in the east region of the Slovak State. In 1944, in the south-east region of the Second Republic of Poland (present territory of Poland), the First Czechoslovak Army Corps was employed alongside the Red Army against the Wehrmacht troops and the fostering Royal Hungarian Army defending the Carpathian passes. Because of the Author’s place of residence, the mentioned regions are particularly close to him. The fact that the Author focused on describing the operations of the First Czechoslovak Army Corps was not coincidental as it were the Czechs and Slovaks who were fighting in its rows. In this thesis, the Author strived to use all the available sources which would describe the subject of the Battle of the Dukla Pass. The collections gathered in the Central Military Archive – Military Historical Archive (cz. Vojenský ústřední archiv - Vojenský historický archiv) served as a valuable source of information. In his work, the Author analyzed extensively a number of studies in Polish, Czech and Slovak. -

Slovakia Michal Hvorecký Interviewed Eva Mosnáková

Slovakia Michal Hvorecký interviewed Eva Mosnáková. Interview date: October 2019 Hvorecký: How was your childhood? Mosnáková: My father was from Nitra. He was an orphan, a Jewish boy. He studied veterinary medicine in Brno. He imbibed modern thinking in the Moravian metropolis. He gave up Jewish traditions and faith. Hvorecký: How did his political thinking develop in Brno? Mosnáková: He became a staunch leftist. He had a strong social awareness. He was probably influenced by the communist thinking which was spreading from the Soviet Union. He became a member of the communist student faction. There, students were more interested in culture than in politics, they recited Jiří Wolker’s poems etc. However, they also denounced Russian emigrants who were supported by the state which some of them took advantage of. First, he admired the USSR. Well, but later, when Russians came, he changed his opinions. Hvorecký: Where is your mother from? Mosnáková: From Moravia, and with humble background. Her father was a military tailor, but probably an invalid, I don’t remember him as a working man. My grandmother was from Moravian Slovakia. She went to live in Brno because of inheritance disputes. She ran a trade on Zelný trh (English: Cabbage market. A traditional street - open air market in Brno) which still exists, she was selling medicinal herbs. Thus, she influenced all her female progeny – I stick to it too. Mother courageously stood by my father even in the worst times. She knew that if fascists arrested her, my father would give himself up. She saved him. She finished two years of trading academy; usually, women were not students at that time. -

Czesław Miłosz (1980), Wisława Szymborska (1996)

- Introduction - Henryk Sienkiewicz (1905), Władysław Reymont (1924), Czesław Miłosz (1980), Wisława Szymborska (1996). How many of you know these four authors and know what they have in common, besides their nationalities? The four of them were awarded a Nobel Prize but nevertheless remain little known outside of Poland. This one example, among many others, proves that Polish literature remains unknown despite its being a big part of European literature. In this class, we shall try to analyse the main aspects of the literary fact in Poland during the 20th century. To quote Czeslaw Milosz, “Polish literature focused more on drama and the poetic expression of the self than on fiction (which dominated the English-speaking world). The reasons find their roots on the historical circumstances of the nation.” Over a first phase, it thus seems important to start out with a broad overview of the general history of Polish literature throughout the ages before we concentrate on the 20th century, which is the main topic of this class but cannot be fully understood without some references to the previous time periods. Polish literature is mainly written in Polish, even though it was enriched with texts in German, Yiddish or Lithuanian… Until the 18th century, Latin was also very much present. Moreover, it is important to keep in mind that Polish literature was also published outside the country. In Polish literature, historical problems have always been an essential characteristic. One can notice that Polish literature is torn between its social duties and literary obligations. With this in mind, it is possible to offer a chronological analysis based on the country’s history, comparing a body of texts with the historical context.