Chapter 10. Thermohaline Circulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 8: Currents

Standards Addressed National Science Lesson 8: Currents Education Standards, Grades 9-12 Unifying concepts and Overview processes Physical science Lesson 8 presents the mechanisms that drive surface and deep ocean currents. The process of global ocean Ocean Literacy circulation is presented, emphasizing the importance of Principles this process for climate regulation. In the activity, students The Earth has one big play a game focused on the primary surface current names ocean with many and locations. features Lesson Objectives DCPS, High School Earth Science Students will: ES.4.8. Explain special 1. Define currents and thermohaline circulation properties of water (e.g., high specific and latent heats) and the influence of large bodies 2. Explain what factors drive deep ocean and surface of water and the water cycle currents on heat transport and therefore weather and 3. Identify the primary ocean currents climate ES.1.4. Recognize the use and limitations of models and Lesson Contents theories as scientific representations of reality ES.6.8 Explain the dynamics 1. Teaching Lesson 8 of oceanic currents, including a. Introduction upwelling, density, and deep b. Lecture Notes water currents, the local c. Additional Resources Labrador Current and the Gulf Stream, and their relationship to global 2. Extra Activity Questions circulation within the marine environment and climate 3. Student Handout 4. Mock Bowl Quiz 1 | P a g e Teaching Lesson 8 Lesson 8 Lesson Outline1 I. Introduction Ask students to describe how they think ocean currents work. They might define ocean currents or discuss the drivers of currents (wind and density gradients). Then, ask them to list all the reasons they can think of that currents might be important to humans and organisms that live in the ocean. -

Ocean Wind and Current Retrievals Based on Satellite SAR Measurements in Conjunction with Buoy and HF Radar Data

remote sensing Article Ocean Wind and Current Retrievals Based on Satellite SAR Measurements in Conjunction with Buoy and HF Radar Data He Fang 1, Tao Xie 1,* ID , William Perrie 2, Li Zhao 1, Jingsong Yang 3 and Yijun He 1 ID 1 School of Marine Sciences, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing 210044, Jiangsu, China; [email protected] (H.F.); [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (Y.H.) 2 Fisheries & Oceans Canada, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, NS B2Y 4A2, Canada; [email protected] 3 State Key Laboratory of Satellite Ocean Environment Dynamics, Second Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, Hangzhou 310012, Zhejiang, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-255-869-5697 Received: 22 September 2017; Accepted: 13 December 2017; Published: 15 December 2017 Abstract: A total of 168 fully polarimetric synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) images are selected together with the buoy measurements of ocean surface wind fields and high-frequency radar measurements of ocean surface currents. Our objective is to investigate the effect of the ocean currents on the retrieved SAR ocean surface wind fields. The results show that, compared to SAR wind fields that are retrieved without taking into account the ocean currents, the accuracy of the winds obtained when ocean currents are taken into account is increased by 0.2–0.3 m/s; the accuracy of the wind direction is improved by 3–4◦. Based on these results, a semi-empirical formula for the errors in the winds and the ocean currents is derived. -

Ocean Circulation and Climate: an Overview

ocean-climate.org Bertrand Delorme Ocean Circulation and Yassir Eddebbar and Climate: an Overview Ocean circulation plays a central role in regulating climate and supporting marine life by transporting heat, carbon, oxygen, and nutrients throughout the world’s ocean. As human-emitted greenhouse gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere, the Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) plays an increasingly important role in sequestering anthropogenic heat and carbon into the deep ocean, thus modulating the course of climate change. Anthropogenic warming, in turn, can influence global ocean circulation through enhancing ocean stratification by warming and freshening the high latitude upper oceans, rendering it an integral part in understanding and predicting climate over the 21st century. The interactions between the MOC and climate are poorly understood and underscore the need for enhanced observations, improved process understanding, and proper model representation of ocean circulation on several spatial and temporal scales. The ocean is in perpetual motion. Through its DRIVING MECHANISMS transport of heat, carbon, plankton, nutrients, and oxygen around the world, ocean circulation regulates Global ocean circulation can be divided into global climate and maintains primary productivity and two major components: i) the fast, wind-driven, marine ecosystems, with widespread implications upper ocean circulation, and ii) the slow, deep for global fisheries, tourism, and the shipping ocean circulation. These two components act industry. Surface and subsurface currents, upwelling, simultaneously to drive the MOC, the movement of downwelling, surface and internal waves, mixing, seawater across basins and depths. eddies, convection, and several other forms of motion act jointly to shape the observed circulation As the name suggests, the wind-driven circulation is of the world’s ocean. -

What Is the Thermohaline Circulation?

S CIENCE’ S C OMPASS PERSPECTIVES 65 flow thus appear to be driven by thermal 64 PERSPECTIVES: OCEANOGRAPHY and evaporative forcing from the atmo- 63 sphere. The ocean seems to act like a heat 62 engine, in analogy to the atmosphere. 61 What Is the Some authors apparently think of this 60 convective mode of motion as the thermo- 59 haline circulation. But results of the past 58 Thermohaline Circulation? few years suggest that such a convectively 57 Carl Wunsch driven mass flux is impossible. There are 56 several lines of argument. The first goes 55 he discussion of today’s climate and mass affect the movements of all other back to Sandström (4), who pointed out that 54 its past and potential future changes properties, such as heat, salt, oxygen, car- when a fluid is heated and cooled at the 53 Tis often framed in the context of the bon, and so forth (1, 2), all of which differ same pressure (or heated at a lower pres- 52 ocean’s thermohaline circulation. Wide- from each other. For example, the North sure), no significant work can be extracted 51 spread consequences are ascribed to its Atlantic imports heat, but exports oxygen. from the flow, with the region below the 50 shutdown and acceleration—a deus ex It seems most sensible to regard the ther- cold source becoming homogeneous. 49 machina for climate change. mohaline circulation –8 –2 The ocean is both 48 But what is meant by this term? In in- as the circulation of 0 heated and cooled ef- 500 47 terdisciplinary fields such as climate temperature and salt. -

Coastal Upwelling Revisited: Ekman, Bakun, and Improved 10.1029/2018JC014187 Upwelling Indices for the U.S

Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans RESEARCH ARTICLE Coastal Upwelling Revisited: Ekman, Bakun, and Improved 10.1029/2018JC014187 Upwelling Indices for the U.S. West Coast Key Points: Michael G. Jacox1,2 , Christopher A. Edwards3 , Elliott L. Hazen1 , and Steven J. Bograd1 • New upwelling indices are presented – for the U.S. West Coast (31 47°N) to 1NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Monterey, CA, USA, 2NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory, Boulder, CO, address shortcomings in historical 3 indices USA, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, USA • The Coastal Upwelling Transport Index (CUTI) estimates vertical volume transport (i.e., Abstract Coastal upwelling is responsible for thriving marine ecosystems and fisheries that are upwelling/downwelling) disproportionately productive relative to their surface area, particularly in the world’s major eastern • The Biologically Effective Upwelling ’ Transport Index (BEUTI) estimates boundary upwelling systems. Along oceanic eastern boundaries, equatorward wind stress and the Earth s vertical nitrate flux rotation combine to drive a near-surface layer of water offshore, a process called Ekman transport. Similarly, positive wind stress curl drives divergence in the surface Ekman layer and consequently upwelling from Supporting Information: below, a process known as Ekman suction. In both cases, displaced water is replaced by upwelling of relatively • Supporting Information S1 nutrient-rich water from below, which stimulates the growth of microscopic phytoplankton that form the base of the marine food web. Ekman theory is foundational and underlies the calculation of upwelling indices Correspondence to: such as the “Bakun Index” that are ubiquitous in eastern boundary upwelling system studies. While generally M. G. Jacox, fi [email protected] valuable rst-order descriptions, these indices and their underlying theory provide an incomplete picture of coastal upwelling. -

The Role of Thermohaline Circulation in Global Climate Change

The Role of Thermohaline Circulation in Global Climate Change • by Arnold Gordon ©&prinlfrom lAmonl-Doherl] Ceologicoi Observatory 1990 & /99/ &PorI Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory of Columbia University Palisades, NY 10964 (914)359-2900 The Role of • The world ocean consists of 1.3 billion cu km of salty water, and covers 70.8% of the Earth's suiface. This enormous body of Thermohaline water exerts a poweiful influence on Earth's climate; indeed, it is an integral part of the global climate system. Therefore, under Circulation in standing the climate system requires a knowledge of how the ocean and the atmosphere exchange heat, water and greenhouse gases. If Global Climate we are to be able to gain a capability for predicting our changing climate we must learn, for example, how pools of warm salty Change water move about the ocean, what governs the growth and decay of sea ice, and how rapidly the deep ocean's interior responds to the changes in the atmosphere. The ocean plays a considerable features for the most part only role in the rate of greenhouse move heat and water on horizon warming. It does this in two tal planes. It is the slower ther ways: it absorbs excess green mohaline circulation, driven by house gases from the atmos buoyancy forcing at the sea sur phere, such as carbon dioxide, face (i.e., exchanges of heat and methane and chlorofluoro fresh water between ocean and methane, and it also absorbs atmosphere change the density • some of the greenhouse-induced or buoyancy of the surface water; by Arnold L. -

In Wind and Ocean Currents

PAPERS IN PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY AND METEOROLOGY PUBLISHED BY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION (In continuation of Massachusetts Institute of Technology Meteorological Papers) VOL. III, NO.3 THE LAYER OF FRICTIONAL INFLUENCE IN WIND AND OCEAN CURRENTS BY c.-G. ROSSBY AND R. B. MONTGOMERY Contribution No. 71 from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution .~ J~\ CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS Ap~il, 1935 CONTENTS i. INTRODUCTION 3 II. ADIABATIC ATMOSPHERE. 4 1. Completion of Solution for Adiabatic Atmosphere 4 2. Light Winds and Residual Turbulence 22 3. A Study of the Homogeneous Layer at Boston 25 4. Second Approximation 4° III. INFLUENCE OF STABILITY 44 I. Review 44 2. Stability in the Boundary Layer 47 3. Stability within Entire Frictional Layer 56 IV. ApPLICATION TO DRIFT CURRENTS. 64 I. General Commen ts . 64 2. The Homogeneous Layer 66 3. Analysis of Material 67 4. Results of Analysis . 69 5. Scattering of the Observations and Advection 72 6. Oceanograph Observations 73 7. Wind Drift of the Ice 75 V. LENGTHRELATION BETWEEN THE VELOCITY PROFILE AND THE VALUE OF THE85 MIXING ApPENDIX2.1. StirringTheoretical in Shallow Comments . Water 92. 8885 REFERENCESSUMMARYModified Computation of the Boundary Layer in Drift Currents 9899 92 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of the present paper is to analyze, in a reasonably comprehensive fash- ion, the principal factors controlling the mean state of turbulence and hence the mean velocity distribution in wind and ocean currents near the surface. The plan of the in- vestigation is theoretical but efforts have been made to check each major step or result through an analysis of available measurements. -

Lecture 4: OCEANS (Outline)

LectureLecture 44 :: OCEANSOCEANS (Outline)(Outline) Basic Structures and Dynamics Ekman transport Geostrophic currents Surface Ocean Circulation Subtropicl gyre Boundary current Deep Ocean Circulation Thermohaline conveyor belt ESS200A Prof. Jin -Yi Yu BasicBasic OceanOcean StructuresStructures Warm up by sunlight! Upper Ocean (~100 m) Shallow, warm upper layer where light is abundant and where most marine life can be found. Deep Ocean Cold, dark, deep ocean where plenty supplies of nutrients and carbon exist. ESS200A No sunlight! Prof. Jin -Yi Yu BasicBasic OceanOcean CurrentCurrent SystemsSystems Upper Ocean surface circulation Deep Ocean deep ocean circulation ESS200A (from “Is The Temperature Rising?”) Prof. Jin -Yi Yu TheThe StateState ofof OceansOceans Temperature warm on the upper ocean, cold in the deeper ocean. Salinity variations determined by evaporation, precipitation, sea-ice formation and melt, and river runoff. Density small in the upper ocean, large in the deeper ocean. ESS200A Prof. Jin -Yi Yu PotentialPotential TemperatureTemperature Potential temperature is very close to temperature in the ocean. The average temperature of the world ocean is about 3.6°C. ESS200A (from Global Physical Climatology ) Prof. Jin -Yi Yu SalinitySalinity E < P Sea-ice formation and melting E > P Salinity is the mass of dissolved salts in a kilogram of seawater. Unit: ‰ (part per thousand; per mil). The average salinity of the world ocean is 34.7‰. Four major factors that affect salinity: evaporation, precipitation, inflow of river water, and sea-ice formation and melting. (from Global Physical Climatology ) ESS200A Prof. Jin -Yi Yu Low density due to absorption of solar energy near the surface. DensityDensity Seawater is almost incompressible, so the density of seawater is always very close to 1000 kg/m 3. -

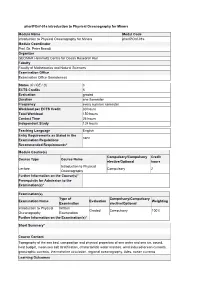

Pheriponf-01A Introduction to Physical Oceanography for Minors Module

pherIPOnf-01a Introduction to Physical Oceanography for Minors Module Name Modul Code Introduction to Physical Oceanography for Minors pherIPOnf-01a Module Coordinator Prof. Dr. Peter Brandt Organizer GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel Fakulty Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences Examination Office Examination Office Geosciences Status (C / CE / O) C ECTS Credits 5 Evaluation graded Duration one Semester Frequency every summer semester Workload per ECTS Credit 30 hours Total Workload 150 hours Contact Time 26 hours Independent Study 124 hours Teaching Language English Entry Requirements as Stated in the none Examination Regulations Recommended Requirements* Module Course(s) Compulsory/Compulsory Credit Course Type Course Name elective/Optional hours Introduction to Physical Lecture Compulsory 2 Oceanography Further Information on the Course(s)* Prerequisits for Admission to the Examination(s)* Examination(s) Type of Compulsory/Compulsory Examination Name Evaluation Weighting Examination elective/Optional Introduction to Physical Written Graded Compulsory 100% Oceanography Examination Further Information on the Examination(s)* Short Summary* Course Content Topography of the sea bed, composition and physical properties of sea water and sea ice, sound, heat budget, mean sea salt stratification, characteristic water masses, wind induced ocean currents, geostrophic currents, thermohaline circulation, regional oceanography, tides, ocean currents Learning Outcomes The students have developed a basic knowledge of the structure and dynamics of the ocean. They are able to understand the most important physical mechanisms in the ocean and to apply this knowledge in the study of subject-specific topics of the continuing modules of meteorology and physical oceanography. Reading List Talley, L.D., G.L. Pickard, W.J. Emery, J.H. -

Oceanography of the Pacific Northwest Coastal Ocean and Estuaries with Application to Coastal Ecosystems

Oceanography of the Pacific Northwest Coastal Ocean and Estuaries with Application to Coastal Ecosystems Barbara M. Hickey1 and Neil S. Banas School of Oceanography Box 355351 University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-7940 Tel.: 206 543 4737 e-mail: [email protected] Submitted to Estuaries May 2002 1Corresponding author. Hickey and Banas 2 Abstract This paper reviews and synthesizes recent results on both the coastal zone of the U.S. Pacific Northwest (PNW) and several of its estuaries, as well as presenting new data from the PNCERS program on links between the inner shelf and the estuaries, and smaller-scale estuarine processes. In general ocean processes are large-scale on this coast: this is true of both seasonal variations and event-scale upwelling-downwelling fluctuations, which are highly energetic. Upwelling supplies most of the nutrients available for production, although the intensity of upwelling increases southward while primary production is higher in the north, off the Washington coast. This discrepancy is attributable to mesoscale features: variations in shelf width and shape, submarine canyons, and the Columbia River plume. These and other mesoscale features (banks, the Juan de Fuca eddy) are important as well in transport and retention of planktonic larvae and harmful algae blooms. The coastal-plain estuaries, with the exception of the Columbia River, are relatively small, with large tidal forcing and highly seasonal direct river inputs that are low-to-negligible during the growing season. As a result primary production in the estuaries is controlled principally not by river-driven stratification but by coastal upwelling and bulk exchange with the ocean. -

Quantifying Thermohaline Circulations: Seawater Isotopic Compositions And

Ocean Sci. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/os-2017-58 Manuscript under review for journal Ocean Sci. Discussion started: 28 July 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Quantifying thermohaline circulations: seawater isotopic compositions 2 and salinity as proxies of the ratio between advection time and 3 evaporation time 4 5 6 Hadar Berman, Nathan Paldor* and Boaz Lazar 7 8 The Fredy and Nadine Herrmann Institute of Earth Sciences 9 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 *Corresponding author, Email address: [email protected] 0 Ocean Sci. Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/os-2017-58 Manuscript under review for journal Ocean Sci. Discussion started: 28 July 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC BY 4.0 License. 23 Abstract 24 Uncertainties in quantitative estimates of the thermohaline circulation in any particular basin 25 are large, partly due to large uncertainties in quantifying excess evaporation over precipitation q x 26 and surface velocities. A single nondimensional parameter, is proposed to h u 27 characterize the “strength” of the thermohaline circulation by combining the physical 28 parameters of surface velocity (u), evaporation rate (q), mixed layer depth (h) and trajectory 29 length (x). Values of can be estimated directly from cross-sections of salinity or seawater 30 isotopic composition (18O and D). Estimates of in the Red Sea and the South-West Indian 31 Ocean are 0.1 and 0.02, respectively, which implies that the thermohaline contribution to the 32 circulation in the former is higher than in the latter. -

Syllabus Physical Oceanography OEAS 405/505/604 Fall 2021

Syllabus Physical Oceanography OEAS 405/505/604 Fall 2021 Instructor: Tal Ezer (683-5631; [email protected]) Office: CCPO, Innovation Research Park I, 4111 Monarch Way, Room 3217 Office Hours: Monday, Wednesday 09:00am-11:00am (email to schedule any other time) Class time: Tuesday, Thursday, 9:15am-10:30pm. First class: Tuesday, August 31. Place: Room 3200, CCPO, Research Bldg. I, 4111 Monarch Way Web page for class notes: http://www.ccpo.odu.edu/~tezer/405_604/ Learning Outcomes: Students will acquire a broad knowledge of the field of Physical Oceanography and learn how scientists in this field collect, analyze and present data for their research. Students will learn about ocean measurements, seawater properties, and the equations of motion that can help us study ocean currents, ocean circulation patterns, waves, tides and other oceanic processes. Prerequisites: One semester of calculus and two semesters of physics, hydraulics or similar courses. Official Textbook – Knauss and Garfield, 2017: Introduction to Physical Oceanography, Third Edition. or Knauss, 1997: Introduction to Physical Oceanography, Second Edition. Other useful books- Stewart, (electronic version, 2008): Introduction to Physical Oceanography (available online) Pickard & Emery, 1982: Descriptive Physical Oceanography More advanced- Pond & Pickard, 1983: Introductory Dynamic Oceanography Mellor, 1996: Introduction to Physical Oceanography Supporting resources: online data, journal articles, computer models, satellite remote sensing, etc. Grading: • Homework assignments: 50%