1 Is Disappointment Inevitable When Dealing with a Work Repeatedly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bring Me the Head of Frank Sinatra! Credit, and That He Keeps Three Loaded Double- in Early 1988

BRING ME THE HEAD OF FRANK “Old No. 6-7/8.” Screw those guys. Really. SINATRA! Jimmy's Bar Introduction If the group is already an adventuring party, then it stands to reason they will be in a tavern. If not, This is a module for 4-6 player characters of level well, they might as well meet at a tavern. 4-6. It is set in a gonzo post-apocalyptic past- Specifcally, Three-Arm Jimmy's, on the Hoboken future. waterfront. What that means, in practical terms, is that it is Three Arm Jimmy's is the sort of generic tavern set in the world presented in Gamma World or that unimaginative Game Masters always start Mutant Future (Encounter Critical could also easily modules in. It's got a bar, manned by Jimmy be used, although the setting is Earth, rather than himself—the extra arm comes in very handy for Vanth or Asteroid 1618). Statistics in this module pulling beers. The bar serves cheap but adequate will be given in Mutant Future terms. beer, a variety of rotgut liquors, most of which are nasty-ass industrial ethanol with a few drops of Other systems can be used, of course: since it favoring agents, and standard bar food, such as has been said that First Edition Gamma World salty deep-fried starchy things, onion rings, was the best edition of Dungeons and Dragons, pickled eggs, and the ubiquitous rat-on-a-stick D&D would work fne, as would Paranoia, Call of (show players Illustration #1). In addition to Cthulhu, Arduin, or an-only-slightly-variant Spawn Jimmy, there will be a waitress and a of Fashan, for instance. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

1 Safety Zone (paragraphs 21 to 77h); (D) the NSO gang’s activities, culture, and values 2 (paragraphs 78 to 91); (E) the NSO’s qualification as a criminal street gang (paragraphs 3 92 to 95); (F) the identification of specific gang members (paragraphs 96 to 109m); and 4 (G) my conclusions in support of injunctive relief against the NSO criminal street gang and 5 all of its members (paragraphs 110 to 111). 6 A. SPECIAL EXPERIENCE, EDUCATION, AND EXPERTISE REGARDING 7 CRIMINAL STREET GANGS AND GANG MEMBERS 8 1. I am a sworn California Law Enforcement officer employed by the Oakland 9 Police Department. I make this declaration in support of the People’s request for a gang 10 injunction and other relief against the North Side Oakland (NSO) criminal street gang 11 within a proposed Safety Zone, located in the City of Oakland. 12 2. In this Declaration, except where I state something to be based on my 13 personal observations, I am stating my opinion as a gang expert, or am referring to 14 information that I used to form my opinions. The information I used to form my opinions on 15 the NSO criminal street gang includes discussions with other law enforcement officers 16 including other gang experts, conversations I have had with members, associates, and 17 affiliates of the NSO criminal street gang, conversations I have had with non-gang 18 members who live and work in the community, and my review of police records, internet 19 materials, music, documentaries, and a review of criminal records of gang members. -

Similar Hats on Similar Heads: Uniformity and Alienation at the Rat Pack’S Summit Conference of Cool

University of Huddersfield Repository Calvert, Dave Similar hats on similar heads: uniformity and alienation at the Rat Pack’s Summit Conference of Cool Original Citation Calvert, Dave (2015) Similar hats on similar heads: uniformity and alienation at the Rat Pack’s Summit Conference of Cool. Popular Music, 34 (1). pp. 1-21. ISSN 0261-1430 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/22182/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Similar hats on similar heads: uniformity and alienation at the Rat Pack’s Summit Conference of Cool Abstract This article considers the nightclub shows of the Rat Pack, focussing particularly on the Summit performances at the Sands Hotel, Las Vegas, in 1960. Featuring Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr, Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop, these shows encompassed musical, comic and dance routines, drawing on the experiences each member had in live vaudeville performance. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Citizen Kane Ebook, Epub

CITIZEN KANE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harlan Lebo | 368 pages | 01 May 2016 | Thomas Dunne Books | 9781250077530 | English | United States Citizen Kane () - IMDb Mankiewicz , who had been writing Mercury radio scripts. One of the long-standing controversies about Citizen Kane has been the authorship of the screenplay. In February Welles supplied Mankiewicz with pages of notes and put him under contract to write the first draft screenplay under the supervision of John Houseman , Welles's former partner in the Mercury Theatre. Welles later explained, "I left him on his own finally, because we'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz's contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, "At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own. The terms of the contract stated that Mankiewicz was to receive no credit for his work, as he was hired as a script doctor. Mankiewicz also threatened to go to the Screen Writers Guild and claim full credit for writing the entire script by himself. After lodging a protest with the Screen Writers Guild, Mankiewicz withdrew it, then vacillated. The guild credit form listed Welles first, Mankiewicz second. Welles's assistant Richard Wilson said that the person who circled Mankiewicz's name in pencil, then drew an arrow that put it in first place, was Welles. -

New Administrators Begin Year Campus Gets

THEOur Vision: “Successful-LAKER Now and Beyond” REVIEWOur Mission: “Learners for Life” Volume 38 Calloway County High School Issue 1 2108 College Farm Road, Murray, Ky. 42071 September 22, 2017 Eclipse New administrators begin year Campus gets Joey Parker reference for the amount of delin- needed facelift Circulation quency of high schoolers. Braden Bogard Teacher Natascha Parrish said, Sports Writer CCHS has a few fresh faces “He is outgoing and has a good this year, and a few familiar ones, rapport with the students as well CCHS opened the school too. as being direct year with a renovated gym floor Our new principal, Chris and disciplined and parking lot. King, began teaching social with them. This The initial step was taken near studies here in 1998. Since makes for an ap- the end of the last school year, then he has also served as proachable, yet when work began on the well- an assistant principal and a respected assis- worn gym floor. guidance counselor, which tant principal, The entrance steps to the makes him well qualified for which is a great gym were also refinished, and the position. combination.” the parking lot was repaved and Teacher Connie Umstead Teacher Ash- Jennifer Stubblefield striped over the summer. CCHS students viewed last month’s eclipse from the Jack D. Rose Stadium. Millions said, “Calloway students, ley Fritsche said A new greenhouse is also across the nation viewed this unusual event in August. faculty, and staff have been that just before scheduled to be completed in the blessed for years with fantas- the first week spring. -

Frank's World

Chris Rojek / Frank Sinatra Final Proof 9.7.2004 10:22pm page 7 one FRANK’S WORLD Frank Sinatra was a World War One baby, born in 1915.1 He became a popular music phenomenon during the Second World War. By his own account, audiences adopted and idol- ized him then not merely as an innovative and accomplished vocalist – his first popular sobriquet was ‘‘the Voice’’ – but also as an appealing symbolic surrogate for American troops fighting abroad. In the late 1940s his career suffered a precipitous de- cline. There were four reasons for this. First, the public perception of Sinatra as a family man devoted to his wife, Nancy, and their children, Nancy, Frank Jr and Tina, was tarnished by his high-octane affair with the film star Ava Gardner. The public face of callow charm and steadfast moral virtue that Sinatra and his publicist George Evans concocted during his elevation to celebrity was damaged by his admitted adultery. Sinatra’s reputation for possessing a violent temper – he punched the gossip columnist Lee Mortimer at Ciro’s night- club2 and took to throwing tantrums and hurling abuse at other reporters when the line of questioning took a turn he disap- proved of – became a public issue at this time. Second, servicemen were understandably resentful of Sina- tra’s celebrity status. They regarded it as having been easily achieved while they fought, and their comrades died, overseas. Some members of the media stirred the pot by insinuating that Sinatra pulled strings to avoid the draft. During the war, like most entertainers, Sinatra made a virtue of his patriotism in his stage act and music/film output. -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

COA Template

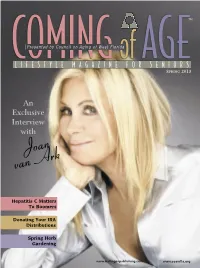

TM COMINGPresented by Council on Aging of West Floridaof AGE LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE FOR SENIORS SPRING 2013 An Exclusive Interview with Joan van Ark Hepatitis C Matters To Boomers Donating Your IRA Distributions Spring Herb Gardening www.ballingerpublishing.com www.coawfla.org COMMUNICATIONS CORNER Jeff Nall, APR, CPRC Editor-in-Chief The groundhog did not see his shadow and we’ve “sprung our clocks forward,” so now it is time to get out and enjoy the many outdoor activities that our area has to offer. Some of my favorites are the free outdoor concerts such as JazzFest, Christopher’s Concerts and Bands on the Beach. I tend to run into many of our readers at these events, but if you haven’t been, check out page 40. For another outdoor option for those with more of a green thumb, check out our article on page 15, which has useful tips for planting an herb garden. This issue also contains important information for baby boomers about Readers’ Services hepatitis C. According to the Centers for Disease Control, people born from Subscriptions Your subscription to Coming of Age 1945 through 1965 account for more than 75 percent of American adults comes automatically with your living with the disease and most do not know they have it. In terms of membership to Council on Aging of financial health, our finance article on page 18 explains how qualified West Florida. If you have questions about your subscription, call Jeff charitable distributions (QCDs) from Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) Nall at (850) 432-1475 ext. 130 or are attractive to some investors because QCDs can be used to satisfy required email [email protected]. -

River Weekly News Read Us Online: LORKEN Publications, Inc

Weather and Tides FREE page 28 Take Me Home VOL. 18, NO. 50 From the Beaches to the River District downtown Fort Myers DECEMBER 13, 2019 per person. Reserve early as seating is Rat Pack limited in the 100-seat center. The multi-evening shows began seven Together Again years ago when Alfredo Russo, the late owner of Junkanoo and the Fresh Catch Returns To Beach Bistro on Fort Myers Beach, wanted he Rat Pack Together Again, a upscale en tertainment for his restaurant group of three entertainers playing guests. Fresh Catch Manager Jerry Nolan TDean Martin, Frank Sinatra and decided to utilize some of his New York Sammy Davis Jr., will return to the connec tions to find the talent. The shows Fort Myers Beach area on Sunday and were an overwhelming success with many Monday, January 26 and 27 to awaken sell-outs. the spirit of the men who were called “the “This is upscale entertainment at coolest cats in entertainment in the early affordable pricing,’’ said Nolan. “If you 1960s” during one of six shows featured look at the pricing, with the dancing, food at the Moose Lodge Entertainment and live shows, it is very economical.” Center. Interest in the shows skyrocketed, Robert Cabella as Dean Martin, Jeff and the crowds became too large for a Foote as Sammy Davis, Jr. and Tony restaurant environment, prompting a Sands as Frank Sinatra will perform as the change in venue to the Moose Lodge leading members of the Rat Pack during Entertainment Center last year. an evening that will last four-plus hours “We needed to move it to more of and include a disc jockey, dancing, a cash a night club atmosphere,” said Nolan, From left, Robert Cabella (Dean Martin), Jeff Foote (Sammy Davis, Jr.) and Tony Sands organizer of the shows. -

Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael: the Duel for the Soul of American Film Criticism

1 Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael: The Duel For the Soul of American Film Criticism By Inge Fossen Høgskolen i Lillehammer / Lillehammer University College Avdeling for TV-utdanning og Filmvitenskap / Department of Television and Film Studies (TVF) Spring 2009 1 2 For My Parents 2 3 ”When we think about art and how it is thought about […] we refer both to the practice of art and the deliberations of criticism.” ―Charles Harrison & Paul Wood “[H]abits of liking and disliking are lodged in the mind.” ―Bernard Berenson “The motion picture is unique […] it is the one medium of expression where America has influenced the rest of the world” ―Iris Barry “[I]f you want to practice something that isn’t a mass art, heaven knows there are plenty of other ways of expressing yourself.” ―Jean Renoir “If it's all in the script, why shoot the film?” ―Nicholas Ray “Author + Subject = Work” ―Andrè Bazin 3 4 Table of Contents Preface and Acknowledgements p. 6. Introduction p. 8. Defining Art in Relation to Criticism p. 14. The Popular As a Common Ground– And an Outline of Study p. 19. Career Overview – Andrew Sarris p. 29. Career Overview – Pauline Kael p. 32. American Film Criticism From its Beginnings to the 1950s – And a Note on Present Challenges p. 35. Notes on Axiological Criticism, With Sarris and Kael as Examples p. 41. Movies: The Desperate Art p. 72. Auteurism – French and American p. 82. Notes on the Auteur Theory 1962 p. 87. "Circles and Squares: Joys and Sarris" – Kael's Rebuttal p. 93. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

THE OTHER SIDE of the WIND; a LOST MOTHER, a MAVERICK, ROUGH MAGIC and a MIRROR: a PSYCHOANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE on the CINEMA of ORSON WELLES by Jack Schwartz

Schwartz, J. (2019). The Other Side of the Wind…A psychoanalytic perspective on the cinema of Orson Welles. MindConsiliums, 19(8), 1-25. THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WIND; A LOST MOTHER, A MAVERICK, ROUGH MAGIC AND A MIRROR: A PSYCHOANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE ON THE CINEMA OF ORSON WELLES By Jack Schwartz ABSTRACT Arguably, Orson Welles is considered America’s most artistic and influential filmmaker from the golden era of American movies, even though most people are only familiar with his first feature, Citizen Kane (1941). Any film buff can easily recognize his signature camera work, his use of lighting and overlapping dialogue, along with so many cinematic nuisances that define his artistry. Despite being on the “pantheon” (Sarris, 1969) of American directors, he never established any real sustaining commercial success. Even though he leaves behind many pieces of a giant beautiful cinematic puzzle, Welles will always be considered one of the greats. Prompted by Welles’ posthumously restored last feature The Other Side of the Wind (2018), the time is ripe for a psychoanalytic re-evaluation of Welles’ cinematic oeuvre, linking the artist’s often tumultuous creative journey to the dynamic structure of Welles’ early and later childhood experiences through the frame of his final film. INTRODUCTION From early in its invention, movies have offered the gift of escaping the grind of daily life, even when movies are sometimes about the grind of daily life. Movies move us, confront us, entertain us, break our hearts, help mend our broken hearts, teach us things, give us a place to practice empathy or express anger and point to injustice.