Local Societies and Nationalizing States in East Central Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Abstracts

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS 1 Institute of Archaeology Belgrade, Serbia 24. LIMES CONGRESS Serbia 02-09 September 2018 Belgrade - Viminacium BOOK OF ABSTRACTS Belgrade 2018 PUBLISHER Institute of Archaeology Kneza Mihaila 35/IV 11000 Belgrade http://www.ai.ac.rs [email protected] Tel. +381 11 2637-191 EDITOR IN CHIEF Miomir Korać Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade EDITORS Snežana Golubović Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade Nemanja Mrđić Institute of Archaeology, Belgrade GRAPHIC DESIGN Nemanja Mrđić PRINTED BY DigitalArt Beograd PRINTED IN 500 copies ISBN 979-86-6439-039-2 4 CONGRESS COMMITTEES Scientific committee Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology (director) Snežana Golubović, Institute of Archaeology Miroslav Vujović, Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Archaeology Stefan Pop-Lazić, Institute of Archaeology Gordana Jeremić, Institute of Archaeology Nemanja Mrđić, Institute of Archaeology International Advisory Committee David Breeze, Durham University, Historic Scotland Rebecca Jones, Historic Environment Scotland Andreas Thiel, Regierungspräsidium Stuttgart, Landesamt für Denkmalpflege, Esslingen Nigel Mills, Heritage Consultant, Interpretation, Strategic Planning, Sustainable Development Sebastian Sommer, Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Lydmil Vagalinski, National Archaeological Institute with Museum – Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Mirjana Sanader, Odsjek za arheologiju Filozofskog fakulteta Sveučilišta u Zagrebu Organization committee Miomir Korać, Institute of Archaeology (director) Snežana Golubović, Institute of Archaeology -

Philo-Germanism Without Germans. Memory, Identity, and Otherness in Post-1989 Romania

Durham E-Theses Philo-Germanism without Germans. Memory, Identity, and Otherness in Post-1989 Romania CERCEL, CRISTIAN,ALEXANDRU How to cite: CERCEL, CRISTIAN,ALEXANDRU (2012) Philo-Germanism without Germans. Memory, Identity, and Otherness in Post-1989 Romania, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4925/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Philo-Germanism without Germans. Memory, Identity, and Otherness in Post-1989 Romania Cristian-Alexandru Cercel PhD School of Government and International Affairs Durham University 2012 3 Abstract The recent history of the German minority in Romania is marked by its mass migration from Romania to Germany, starting roughly in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War and reaching its climax in the early 1990s, following the fall of Communism. Against this background, the present thesis investigates a phenomenon that can be termed “philo-Germanism without Germans”, arguing that the way the German minority in Romania is represented in a wide array of discourses is best comprehended if placed in a theoretical framework in which concepts such as “self-Orientalism”, “intimate colonization” and other related ones play a key role. -

Ephemeris Napocensis

EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS XXII 2012 ROMANIAN ACADEMY INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ART CLUJ-NAPOCA EDITORIAL BOARD Editor: Coriolan Horaţiu Opreanu Members: Sorin Cociş, Vlad-Andrei Lăzărescu, Ioan Stanciu ADVISORY BOARD Alexandru Avram (Le Mans, France); Mihai Bărbulescu (Rome, Italy); Alexander Bursche (Warsaw, Poland); Falko Daim (Mainz, Germany); Andreas Lippert (Vienna, Austria); Bernd Pägen (Munich, Germany); Marius Porumb (Cluj-Napoca, Romania); Alexander Rubel (Iași, Romania); Peter Scherrer (Graz, Austria); Alexandru Vulpe (Bucharest, Romania). Responsible of the volume: Ioan Stanciu În ţară revista se poate procura prin poştă, pe bază de abonament la: EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE, Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, sector 5, P. O. Box 5–42, Bucureşti, România, RO–76117, Tel. 021–411.90.08, 021–410.32.00; fax. 021–410.39.83; RODIPET SA, Piaţa Presei Libere nr. 1, Sector 1, P. O. Box 33–57, Fax 021–222.64.07. Tel. 021–618.51.03, 021–222.41.26, Bucureşti, România; ORION PRESS IMPEX 2000, P. O. Box 77–19, Bucureşti 3 – România, Tel. 021–301.87.86, 021–335.02.96. EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS Any correspondence will be sent to the editor: INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI Str. M. Kogălniceanu nr. 12–14, 400084 Cluj-Napoca, RO e-mail: [email protected] All responsability for the content, interpretations and opinions expressed in the volume belongs exclusively to the authors. DTP and print: MEGA PRINT Cover: Roxana Sfârlea © 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, Sector 5, Bucureşti 76117 Telefon 021–410.38.46; 021–410.32.00/2107, 2119 ACADEMIA ROMÂNĂ INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS XXII 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE SOMMAIRE – CONTENTS – INHALT STUDIES FLORIN GOGÂLTAN Ritual Aspects of the Bronze Age Tell-Settlements in the Carpathian Basin. -

Ephemeris Napocensis

EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS XXII 2012 ROMANIAN ACADEMY INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ART CLUJ-NAPOCA EDITORIAL BOARD Editor: Coriolan Horaţiu Opreanu Members: Sorin Cociş, Vlad-Andrei Lăzărescu, Ioan Stanciu ADVISORY BOARD Alexandru Avram (Le Mans, France); Mihai Bărbulescu (Rome, Italy); Alexander Bursche (Warsaw, Poland); Falko Daim (Mainz, Germany); Andreas Lippert (Vienna, Austria); Bernd Pägen (Munich, Germany); Marius Porumb (Cluj-Napoca, Romania); Alexander Rubel (Iași, Romania); Peter Scherrer (Graz, Austria); Alexandru Vulpe (Bucharest, Romania). Responsible of the volume: Ioan Stanciu În ţară revista se poate procura prin poştă, pe bază de abonament la: EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE, Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, sector 5, P. O. Box 5–42, Bucureşti, România, RO–76117, Tel. 021–411.90.08, 021–410.32.00; fax. 021–410.39.83; RODIPET SA, Piaţa Presei Libere nr. 1, Sector 1, P. O. Box 33–57, Fax 021–222.64.07. Tel. 021–618.51.03, 021–222.41.26, Bucureşti, România; ORION PRESS IMPEX 2000, P. O. Box 77–19, Bucureşti 3 – România, Tel. 021–301.87.86, 021–335.02.96. EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS Any correspondence will be sent to the editor: INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI Str. M. Kogălniceanu nr. 12–14, 400084 Cluj-Napoca, RO e-mail: [email protected] All responsability for the content, interpretations and opinions expressed in the volume belongs exclusively to the authors. DTP and print: MEGA PRINT Cover: Roxana Sfârlea © 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, Sector 5, Bucureşti 76117 Telefon 021–410.38.46; 021–410.32.00/2107, 2119 ACADEMIA ROMÂNĂ INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS XXII 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE SOMMAIRE – CONTENTS – INHALT STUDIES FLORIN GOGÂLTAN Ritual Aspects of the Bronze Age Tell-Settlements in the Carpathian Basin. -

R O M a N I a N M E D I E V a L

R O M A N I A N Thraco-Dacian and Byzantine Romanity of Eastern Europe and Asia Minor M E D I E V A L I A New York City, New York (Volume II, III and IV) Papers presented at the: 37th; 38th; and 39th International Congress on Medieval Studies Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan (2-5 May 2002; (8-11 May 2003); 6-9 May 2004) Edited and published by The Romanian Institute of Orthodox Theology and Spirituality New York, N. Y. and sponsored by The Romanian-American Heritage Center, Jackson, Michigan EDITORIAL BOARD: Editor in Chief: George Alexe Editors: Theodor Damian, Eugene S. Raica, and Gale Bellas The papers presented at the International Congress on Medieval Studies and published here do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the Romanian Institute of Orthodox Theology and Spirituality, New York City, N.Y. Donations toward the cost of printing and mailing are welcome and tax-deductible, payable by check or money order to the “Romanian Medievalia” forwarded to Editor in Chief, George Alexe, 19965 Riopelle Street, Detroit, Michigan 48203-1249. Correspondence concerning Romanian Medievalia should be directed to the Editor in Chief: George Alexe, 19965 Riopelle Street, Detroit, Michigan 48203-1249, E-mail: [email protected] or to the President of the Romanian Institute of Orthodox Theology and Spirituality, Rev. Prof. Theodor Damian, 30-18 50th Street, Woodside, New York 11377, E-mail: [email protected] ISSN: 1539-5820 ISBN: 1-888-067-13-6 2 THE ROMANIAN INSTITUTE OF ORTHODOX THEOLOGY AND SPIRITUALITY, NEW YORK, NY ROMANIAN THRACO-DACIAN AND BYZANTINE ROMANITY OF EASTERN EUROPE AND ASIA MINOR MEDIEVALIA NEW YORK, VOL. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Personal: Name: Deac Surname: Dan Augustin Nationality: Romanian. Gender: Male. Date of Birth: August 12th 1986. Contact: e-mail address: [email protected] Education: 2001-2005- High School: Silvania National College, Zalău. 2005-2008- History and Philosophy Faculty, Department of Classical Studies and Archaeology, Babeș- Bolyai University, Cluj- Napoca. Thesis: Dicționar hieroglific egiptean (Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary) (The First dictionary of this kind in Romanian); highest degree (10 out of 10 points), coordinator Conf. Dr. Alexandru Diaconescu, Babeș- Bolyai University, Cluj- Napoca. 2008-2010- MA of Classical Studies and Archaeology, Babeș- Bolyai University, Cluj- Napoca: Thesis: Influențele egiptene în Dacia romană (Egyptian Influences in Roman Dacia); highest degree (10 out of 10 points), coordinator: Conf. Dr. Alexandru Diaconescu, Babeș- Bolyai University, Cluj- Napoca. 2010-2013- PhD study: Prezența și influențele egiptene la Dunărea de Mijloc și de Jos: Provinciile pannonice, moesice și dacice (sec. I- IV e.n.), trans. The Egyptian Influences and Presence at the Middle and Lower Danube: The Pannonian, Moesian and Dacian Provinces (I-IV c. A.D.) coordinator: Prof. Dr. Mihai Bărbulescu, Dirretore della Academia di Romania, Roma. Defended on January 15th 2014. Languages: Romanian (mother tongue); English; German (fluent); Italian; French; Spanish (reading); Latin; Ancient Greek; Ancient Egyptian (with dictionary). Occupation: 2010 October- 2013 September: Doctoral student at the School of Culture, History and Civilization of the Babeș- Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania. 2014 January- 2015 September: Research Assistant History and Art County Museum, Zalău, Romania. 2015 October- 2017 September: Researcher, Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj- Napoca (part-time). 2015 October- : Researcher History and Art County Museum, Zalău, Romania. -

The Activism of the Middle Clergy in Support of the National Desideratum

The Activism of the Middle Clergy in Support of the National Desideratum A NDREE A D ÃNCIL Ã-I NEO A N Romanian Archpriests at the Great O VIDIU E MIL I UDE A N National Assembly in Alba Iulia IN ETHNICALLY and confessionally- As vectors of mobilization, heterogeneous regions, such as Tran- archpriests not only wel- sylvania, the arch- and parish priests not only shepherded their communi- comed the national scenario ties in a spiritual sense, but also took underway in November on the mantle of de-facto guides in the tangled web of nationalist movements and December 1918, but and political affirmation. also translated the new era In the case of the Orthodox and Greek Catholic denominations, domi- to their communities nant from a quantitative perspective of devotion, continuing during the 19th and 20th centuries in to guide them spiritually Transylvania, but whose adherents were politically marginalized and con- and temporally. trolled few mechanisms of influencing state policy, the middle clergy saw it- self placed between the often compet- ing interests and necessities of their Andreea Dãncilã-Ineoan respective churches, their (sometimes Research assistant, Center for Population ethnically-mixed) communities, and Studies, Babeº-Bolyai University, Cluj- the succeeding configurations of state Napoca. power in Transylvania. The ways in which they responded to the challeng- Ovidiu Emil Iudean Research assistant, Center for Population The study was supported through the Studies, Babeº-Bolyai University, Cluj- grant CNCS–UEFISCDI, project no. PN-III-P4- Napoca. ID-PCE–2016-0661. PARADIGMS • 35 es posed by these ambivalent settings should be regarded as a function of their upbringing, family and social-economic background, education, and individual or group strategies. -

UA Campus Repository

A history of Romanian historical writing Item Type Book Authors Kellogg, Frederick Publisher C. Schlacks Download date 07/10/2021 14:16:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/316020 r 1 UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 111 111 1 1111 39001029167551 A 2(6.7 i4\14c- i5w)A HISTORY OF ROMANIAN HISTORICAL WRITING Frederick jCellogg Charles Schlacks, Jr., Publisher Bakersfield, California Charles Schlacks, Jr., Publisher Arts and Sciences California State University, Bakersfield 9001 Stockdale Highway Bakersfield, California 93311-1099 Copyright ©1990 by Frederick Kellogg All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: Kellogg, Frederick. A history of Romanian historical writing / Frederick Kellogg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Romanian-Historiography. I. Title DR216.7.K45 1990 949.8'0072-dc20 89-70330 CIP Frederick Kellogg is Associate Professor of History at the University of Arizona. CONTENTS Preface vii Illustrations (Before page 1) 1 Early Historical Writing in the Romanian Lands 1 2 Modern Romanian Historical Writing 24 3 Contemporary Romanian Historical Writing 52 4 Foreign Views on Romanian History 71 5 Resources and Organization of Romanian Historical Research 95 6 Current Needs of Romanian Historiography 107 APPENDICES A.Brief Chronology of the Carpatho-Danubian Region 111 B.Map of the Carpatho-Danubian Region 117 Bibliography 119 Index 129 TABLE OF ILLUSTRATIONS (before page 1) 1. The Stolnic Constantin Cantacuzino (1640-1716) 2. Dimitrie Cantemir (1673-1723) 3. Petru Maior (1761-1821) 4. Gheorghe Sincai (1754-1816) 5. Nicolae Balcescu (1819-1852) 6. Mihail Kogalniceanu (1817-1891) 7. Andrei Saguna (1809-1873) 8. -

Ephemeris Napocensis

EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS XXII 2012 ROMANIAN ACADEMY INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ART CLUJ-NAPOCA EDITORIAL BOARD Editor: Coriolan Horaţiu Opreanu Members: Sorin Cociş, Vlad-Andrei Lăzărescu, Ioan Stanciu ADVISORY BOARD Alexandru Avram (Le Mans, France); Mihai Bărbulescu (Rome, Italy); Alexander Bursche (Warsaw, Poland); Falko Daim (Mainz, Germany); Andreas Lippert (Vienna, Austria); Bernd Päffgen (Munich, Germany); Marius Porumb (Cluj-Napoca, Romania); Alexander Rubel (Iași, Romania); Peter Scherrer (Graz, Austria); Alexandru Vulpe (Bucharest, Romania). Responsible of the volume: Ioan Stanciu În ţară revista se poate procura prin poştă, pe bază de abonament la: EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE, Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, sector 5, P. O. Box 5–42, Bucureşti, România, RO–76117, Tel. 021–411.90.08, 021–410.32.00; fax. 021–410.39.83; RODIPET SA, Piaţa Presei Libere nr. 1, Sector 1, P. O. Box 33–57, Fax 021–222.64.07. Tel. 021–618.51.03, 021–222.41.26, Bucureşti, România; ORION PRESS IMPEX 2000, P. O. Box 77–19, Bucureşti 3 – România, Tel. 021–301.87.86, 021–335.02.96. EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS Any correspondence will be sent to the editor: INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI Str. M. Kogălniceanu nr. 12–14, 400084 Cluj-Napoca, RO e-mail: [email protected] All responsability for the content, interpretations and opinions expressed in the volume belongs exclusively to the authors. DTP and print: MEGA PRINT Cover: Roxana Sfârlea © 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, Sector 5, Bucureşti 76117 Telefon 021–410.38.46; 021–410.32.00/2107, 2119 ACADEMIA ROMÂNĂ INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS XXII 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE SOMMAIRE – CONTENTS – INHALT STUDIES FLORIN GOGÂLTAN Ritual Aspects of the Bronze Age Tell-Settlements in the Carpathian Basin. -

Ephemeris Napocensis

EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS XXII 2012 ROMANIAN ACADEMY INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY OF ART CLUJ-NAPOCA EDITORIAL BOARD Editor: Coriolan Horaţiu Opreanu Members: Sorin Cociş, Vlad-Andrei Lăzărescu, Ioan Stanciu ADVISORY BOARD Alexandru Avram (Le Mans, France); Mihai Bărbulescu (Rome, Italy); Alexander Bursche (Warsaw, Poland); Falko Daim (Mainz, Germany); Andreas Lippert (Vienna, Austria); Bernd Päffgen (Munich, Germany); Marius Porumb (Cluj-Napoca, Romania); Alexander Rubel (Iași, Romania); Peter Scherrer (Graz, Austria); Alexandru Vulpe (Bucharest, Romania). Responsible of the volume: Ioan Stanciu În ţară revista se poate procura prin poştă, pe bază de abonament la: EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE, Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, sector 5, P. O. Box 5–42, Bucureşti, România, RO–76117, Tel. 021–411.90.08, 021–410.32.00; fax. 021–410.39.83; RODIPET SA, Piaţa Presei Libere nr. 1, Sector 1, P. O. Box 33–57, Fax 021–222.64.07. Tel. 021–618.51.03, 021–222.41.26, Bucureşti, România; ORION PRESS IMPEX 2000, P. O. Box 77–19, Bucureşti 3 – România, Tel. 021–301.87.86, 021–335.02.96. EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS Any correspondence will be sent to the editor: INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI Str. M. Kogălniceanu nr. 12–14, 400084 Cluj-Napoca, RO e-mail: [email protected] All responsability for the content, interpretations and opinions expressed in the volume belongs exclusively to the authors. DTP and print: MEGA PRINT Cover: Roxana Sfârlea © 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE Calea 13 Septembrie nr. 13, Sector 5, Bucureşti 76117 Telefon 021–410.38.46; 021–410.32.00/2107, 2119 ACADEMIA ROMÂNĂ INSTITUTUL DE ARHEOLOGIE ŞI ISTORIA ARTEI EPHEMERIS NAPOCENSIS XXII 2012 EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE SOMMAIRE – CONTENTS – INHALT STUDIES FLORIN GOGÂLTAN Ritual Aspects of the Bronze Age Tell-Settlements in the Carpathian Basin. -

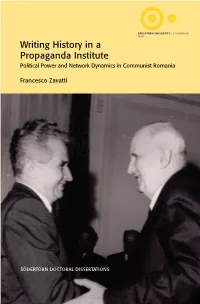

Writing History in a Propaganda Institute

WRITING HISTORY IN A PROPAGANDA INSTITUTE INSTITUTE WRITING IN A PROPAGANDA HISTORY Writing History in a Propaganda Institute Romania’s Party History Institute has been portrayed as a loyal ex- Political Power and Network Dynamics in Communist Romania ecutioner of the Communist Party’s will. Yet, recent investigations of the institute’s archive tell a diff erent story. Francesco Zavatti In 1990, the Institute for Historical and Socio-Political Studies of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party (previously the Party History Institute) was closed. Since its foundation in 1951 it had produced thousands of books and journals for the Communist Party on the history of both the Party and Romania. Th is book is dedicated to the study of the Party History Institute, the history-writers employed there and the narratives they produced. By studying the history-writers and their host institution, the his- toriography produced under Communist rule has been re-contextu- alized. For the fi rst time, this highly controversial institute and its vacillating role are scrutinized by a scholarly eye. Francesco Zavatti is a historian at Södertörn University, Sweden, and is affi liated with the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES) and the School of Historical and Contemporary Studies. Francesco Zavatti Francesco Distribution: Södertörn University, Library, SE-141 89 Huddinge. [email protected] SÖDERTÖRN DOCTORAL DISSERTATIONS Writing History in a Propaganda Institute Writing History in a Propaganda Institute Political Power and Network Dynamics in Communist Romania Francesco Zavatti Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © Francesco Zavatti Cover image: Fotografia #LA079, Fototeca online a comunismului românesc (Online communism photo collection, National Archives of Romania 01.03.2016), (ANIC, fondul ISISP, 79/1976: Solemnitatea decorării lui Ion Popescu-Puţuri la împlinirea vârstei de 70 de ani cu „Steaua Republicii Socialiste România” cls. -

Great Britain, British Jews, and the International Protection of Romanian Jews, 1900–1914

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 56 Satu Matikainen Great Britain, British Jews, and the International Protection of Romanian Jews, 1900–1914 A Study of Jewish Diplomacy and Minority Rights JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Copyright © , by University of Jyväskylä ABSTRACT Matikainen, Satu Great Britain, British Jews, and the international protection of Romanian Jews, 1900-1914: A study of Jewish diplomacy and minority rights Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2006, 234 p. (Jyväskylä Studies on Humanities ISSN 1459-4323; 56) ISBN 951-39-2567-6 Finnish summary Diss. The thesis discusses the Romanian Jewish problem in the early twentieth century from the perspective of Jewish diplomacy and minority rights. The number of Jews in Romania was approximately 270,000, or 4.5 per cent of the total population. The Romanian Jews were one of the first minority groups to be protected by means of international conventions. The Treaty of Berlin (1878) provided for equal rights to persons of all religious confessions in Romania. However, Jews were not granted Romanian citizenship, and their lives were regulated by a system of anti-Jewish legislation. In this situation, emancipated Jewish elites in Western Europe, including Britain, strove to help their coreligionists in Romania. British Jews, through their foreign policy organisation, the Conjoint Foreign Committee, tried to persuade the British Foreign Office to intervene on behalf of Romanian Jews. The British government agreed, in principle, that Romanian Jewish policy should be modified. It was reluctant to act, however, arguing that any intervention in Romanian affairs could only happen in concert with the other Great Powers. The attitudes of the British government towards Romanian Jews were shaped in part by interpretations on international minority protection.