Compositional Analysis of French Colonial Ceramics: Implications for Understanding Trade and Exchange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ETI Energy Snapshot

Martinique U.S. Department of Energy Energy Snapshot Population and Economy Population Size 375,435 GDP per Capita $25,927 Total Area Size 1,128 Sq. Kilometers Share of GDP Spent on Fuel Imports 6% Total GDP $9.8 Billion Urban Population Percentage 89.1% Electricity Sector Overview Electricity Generation Mix (2017) Installed Capacity 543 MW 75.1% Fossil Fuels (Diesel) RE Installed Capacity Share 24% Peak Demand (2019) 235 MW (estimated) Total Generation (2019) 1,527 GWh 16.4% Biomass Transmission and Distribution Losses 10% 5.5%* 3.0% Solar Wind Average Electricity Rates (USD/kWh) *does not include off-grid installed systems Residential $1.09 Small Business $1.14 Large Business $0.92 Electricity Consumption by Sector 51.5% Commercial, Hotels, Public Buildings 37.7% Residential 10.8% Industrial & Farming Renewable Energy Status Targets Renewable Energy Generation Solar Biomass Wind 100% by 2030 https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/outermost-regions/ pdf/energy_report_en.pdf Energy Efficiency Reduce 118 GWh of electricity consumption by 2023 76.7 MW** 41.4 MW 13.0 MW **includes off-grid installed systems Existing Policy and Regulatory Framework Government and Utility Renewable Feed-in Tariff Government Institution for Energy Energy Net Metering and Billing French Environment and Energy Management Agency (ADEME) Interconnection Standards https://www.ademe.fr/en Energy Access (Electrification Rate) Préfet De La Martinique Renewable Portfolio Standard http://www.martinique.gouv.fr/ Tax Credits Collectivite www.collectivitedemartinique.mq Tax Reduction or Exemption Regulatory Entities Public Loans or Grants Collectivité Terriotoriale de Martinique Auctions or Reverse Auctions https://www.cre.fr/en Green Public Procurement Utility(s) Electricité de France S.A. -

The History and Development of the Saint Lucia Civil Code N

Document generated on 10/01/2021 11:30 p.m. Revue générale de droit THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE SAINT LUCIA CIVIL CODE N. J. O. Liverpool Volume 14, Number 2, 1983 Article abstract The Civil Code of St. Lucia was copied almost verbatim from the Québec Civil URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1059340ar Code and promulgated in the island in 1879, with minor influences from the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1059340ar Civil Code of Louisiana. It has constantly marvelled both West Indians and visitors to the region alike, See table of contents that of all the former British Caribbean territories which were subjected to the vicissitudes of the armed struggles in the region between the Metropolitan powers resulting infrequent changes is sovereignty from one power to the Publisher(s) other, only St. Lucia, after seventy-six years of uninterrupted British rule since its last cession by the French, managed to introduce a Civil Code which in effect Éditions de l’Université d’Ottawa was in direct conflict in most respects with the laws obtaining in its parent country. ISSN This is an attempt to examine the forces which were constantly at work in 0035-3086 (print) order to achieve this end, and the resoluteness of their efforts. 2292-2512 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Liverpool, N. J. O. (1983). THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE SAINT LUCIA CIVIL CODE. Revue générale de droit, 14(2), 373–407. https://doi.org/10.7202/1059340ar Droits d'auteur © Faculté de droit, Section de droit civil, Université d'Ottawa, This document is protected by copyright law. -

Iguana Iguana

Genetic evidence of hybridization between the endangered native species Iguana delicatissima and the invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in the Lesser Antilles: management Implications Barbara Vuillaume, Victorien Valette, Olivier Lepais, Frederic Grandjean, Michel Breuil To cite this version: Barbara Vuillaume, Victorien Valette, Olivier Lepais, Frederic Grandjean, Michel Breuil. Genetic evidence of hybridization between the endangered native species Iguana delicatissima and the invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in the Lesser Antilles: management Implications. PLoS ONE, Public Library of Science, 2015, 10 (6), 10.1371/journal.pone.0127575. hal-01901355 HAL Id: hal-01901355 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01901355 Submitted on 27 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic Evidence of Hybridization between the Endangered Native Species Iguana delicatissima and the Invasive Iguana iguana (Reptilia, Iguanidae) in -

Critical Care Medicine in the French Territories in the Americas

01 Pan American Journal Opinion and analysis of Public Health 02 03 04 05 06 Critical care medicine in the French Territories in 07 08 the Americas: Current situation and prospects 09 10 11 1 2 1 1 1 Hatem Kallel , Dabor Resiere , Stéphanie Houcke , Didier Hommel , Jean Marc Pujo , 12 Frederic Martino3, Michel Carles3, and Hossein Mehdaoui2; Antilles-Guyane Association of 13 14 Critical Care Medicine 15 16 17 18 Suggested citation Kallel H, Resiere D, Houcke S, Hommel D, Pujo JM, Martino F, et al. Critical care medicine in the French Territories in the 19 Americas: current situation and prospects. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2021;45:e46. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2021.46 20 21 22 23 ABSTRACT Hospitals in the French Territories in the Americas (FTA) work according to international and French stan- 24 dards. This paper aims to describe different aspects of critical care in the FTA. For this, we reviewed official 25 information about population size and intensive care unit (ICU) bed capacity in the FTA and literature on FTA ICU specificities. Persons living in or visiting the FTA are exposed to specific risks, mainly severe road traffic 26 injuries, envenoming, stab or ballistic wounds, and emergent tropical infectious diseases. These diseases may 27 require specific knowledge and critical care management. However, there are not enough ICU beds in the FTA. 28 Indeed, there are 7.2 ICU beds/100 000 population in Guadeloupe, 7.2 in Martinique, and 4.5 in French Gui- 29 ana. In addition, seriously ill patients in remote areas regularly have to be transferred, most often by helicopter, 30 resulting in a delay in admission to intensive care. -

PROLOGUE Josephine Beheaded

PROLOGUE Josephine Beheaded Marble like Greece, like Faulkner’s South in stone Deciduous beauty prospered and is gone . —Derek Walcott, “Ruins of a Great House,” Collected Poems There is a spectacle in Martinique’s gracious Savane park that is hard to miss. The statue honoring one of the island’s most famous citizens, Josephine Tascher, the white creole woman who was to become Napoleon’s lover, wife, and empress, is defaced in the most curious and creative of ways. Her head is missing; she has been decapitated. But this is no ordinary defacement: the marble head has been cleanly sawed off—an effort that could not have been executed without the help of machinery and more than one pair of willing hands—and red paint has been dripped from her neck and her gown. The defacement is a beheading, a reenactment of the most visible of revolutionary France’s punitive and socially purifying acts—death by guillotine. The biographical record shows Josephine born of a slaveholding family of declining fortunes, married into the ranks of France’s minor aristocracy, and surviving the social chaos of the French Revolution, which sentenced countless members of the ancien régime to the guillotine. In the form of this statue, she received her comeuppance in twentieth-century Martinique, where she met the fate that she narrowly missed a century earlier. Scratched on the pedestal are the words—painted in red and penned in creole— “Respe ba Matinik. Respe ba 22 Me” [Respect Martinique. Respect May 22]. The date inscribed here of the anniversary of the 1848 slave rebellion that led to the abolition of slavery on Martinique is itself an act of postcolonial reinscription, one that challenges the of‹cial French-authored abolition proclamation of March 31, 1848, and 2 CULTURAL CONUNDRUMS Statue of Josephine in Fort-de-France, Martinique, today. -

French Geothermal Resources Survey BRGM Contribution to the Market Study in the LOW-BIN Project

French geothermal resources survey BRGM contribution to the market study in the LOW-BIN project BRGM/RP - 57583 - FR August, 2009 French geothermal resources survey BRGM contribution to the market study in the LOW-BIN project (TREN/05/FP6EN/S07.53962/518277) BRGM/RP-57583-FR August, 2009 F. Jaudin With the collaboration of M. Le Brun, V.Bouchot, C. Dezaye IM 003 ANG – April 05 Keywords: French geothermal resources, geothermal heat, geothermal electricity generation schemes, geothermal Rankine Cycle, cogeneration, geothermal binary plants In bibliography, this report should be cited as follows: Jaudin F. , Le Brun M., Bouchot V., Dezaye C. (2009) - French geothermal resources survey, BRGM contribution to the market study in the LOW-BIN Project. BRGM/RP-57583 - FR © BRGM, 2009. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior permission of BRGM French geothermal resources survey BRGM contribution to the market study in the LOW-BIN Project BRGM, July 2009 F.JAUDIN M. LE BRUN, V. BOUCHOT, C. DEZAYE 1 / 33 TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................4 2. The sedimentary regions...................................................................................................5 2.1. The Paris Basin ........................................................................................................5 2.1.1. An overview of the exploitation of the low enthalpy Dogger reservoir ..............7 2.1.2. The geothermal potential -

Sales Manual

Sales manual 2014-2015 omin al de D ique Can Nord-Plage Macouba Grand'Rivière Basse-Pointe JM CRASSOUS DE MEDEUIL Forêt Départementale Ajoupa- Moulin Lorrain Domaniale de la à Cannes Bouillon N1 Fabrique de Manioc Anse Couleuvre Montagne Pelée La Maison et de Cassaves Les Gorges de la Poupée Montagne Pelée de la Falaise Marigot Prêcheur 1395 m N3 N1 Le Tombeau P D15 des Caraïbes a Sainte-Marie rc Morne-Rouge N Réserve Naturelle Edito a Îlets D10 Le Cap 21 tu Coopérative de la Caravelle r Morne Jacob SAINT JAMES Ste Marie e de vannerie D2 DEPAZ Maison N3 l R 884 m D24 Paille Caraïbes Château de la Nature é Presqu’île g Dubuc D25 de la Caravelle D11 io n D1 a Morne des Esses Fond- l HARDY Saint-Pierre D1 d D2 La Sora OCÉAN St-Denis e D15 l a Trinité M N4 Ba on HABITATION D26 ie du Gali ATLANTIQUE NEISSON D20 Morne-Vert a SAINT-ETIENNE N1 r t i D1 Carbet Piton n Aqualand La i Gros-Morne This Sales Manual was designed to help q Miellerie du Carnet u D1 Les îlets du Robert D20 1196 m e Vert-Pré N3 you set up programming and sell the Bellefontaine D3 Havre du Robert D27 An Griyav La Robert D63 Saint-Joseph destination. It will help you design products D14 D15 D47 N4 D13 D45 D3 and tourism packages and answer all Case-Pilote N2 FORT-DE-FRANCE CLEMENTD. 1 N6 v N1 D30 er Les îlets du François your clients’ questions. -

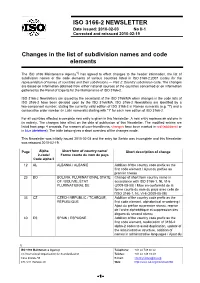

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

The Outermost Regions European Lands in the World

THE OUTERMOST REGIONS EUROPEAN LANDS IN THE WORLD Açores Madeira Saint-Martin Canarias Guadeloupe Martinique Guyane Mayotte La Réunion Regional and Urban Policy Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed. European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy Communication Agnès Monfret Avenue de Beaulieu 1 – 1160 Bruxelles Email: [email protected] Internet: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/index_en.htm This publication is printed in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese and is available at: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/activity/outermost/index_en.cfm © Copyrights: Cover: iStockphoto – Shutterstock; page 6: iStockphoto; page 8: EC; page 9: EC; page 11: iStockphoto; EC; page 13: EC; page 14: EC; page 15: EC; page 17: iStockphoto; page 18: EC; page 19: EC; page 21: iStockphoto; page 22: EC; page 23: EC; page 27: iStockphoto; page 28: EC; page 29: EC; page 30: EC; page 32: iStockphoto; page 33: iStockphoto; page 34: iStockphoto; page 35: EC; page 37: iStockphoto; page 38: EC; page 39: EC; page 41: iStockphoto; page 42: EC; page 43: EC; page 45: iStockphoto; page 46: EC; page 47: EC. Source of statistics: Eurostat 2014 The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the position or opinion of the European Commission. More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. -

Les Établissements De Santé Dans Les DROM : Activité Et Capacités

Les établissements de santé 08 dans les DROM : activité et capacités L’organisation sanitaire des cinq départements et régions d’outre-mer (DROM) revêt une grande diversité. La Guadeloupe et la Martinique ont une capacité d’accueil et une activité hospitalières comparables à celles de la métropole. À l’opposé, en Guyane, à La Réunion et plus encore à Mayotte, les capacités d’accueil, rapportées à la population, sont nettement moins élevées et moins variées. Les départements et régions d’outre-mer (DROM) des trois autres DROM, dont le taux d’équipement en ont une organisation sanitaire très contrainte par leur hospitalisation partielle est nettement en deçà. géographie. Les Antilles, La Réunion et Mayotte sont En psychiatrie, le nombre de lits d’hospitalisation des départements insulaires, alors que la Guyane complète en Guadeloupe et en Martinique, rapporté est un vaste territoire faiblement peuplé. De plus, si, à leur population, est proche de celui de la métro- en Martinique et en Guadeloupe, la structure d’âge pole (84 lits pour 100 000 habitants). La Réunion est proche de celle de la métropole, la population et la Guyane ont des taux d’équipement plus faibles, est nettement plus jeune à Mayotte, à La Réunion tandis qu’à Mayotte il est quasi nul. Le taux d’équipe- et en Guyane. ment en hospitalisation partielle de psychiatrie des En 2018, la population des DROM représente 3,3 % DROM est nettement plus bas qu’en métropole, sauf de la population de la France, soit 2,2 millions de en Guadeloupe. personnes. La Guyane et Mayotte sont les seules En soins de suite et de réadaptation (SSR, moyen régions françaises, avec la Corse en métropole, séjour), les écarts de capacités d’accueil en hospi- à ne pas avoir de centre hospitalier régional (CHR) talisation complète sont également marqués entre [tableau 1]. -

Le Francois - FRENCH MARTINIQUE (FR.) Algae Bloom Coastline

GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR282 Legend Product N.: 05LEFRANCOIS, v1, English Crisis Information Hydrography Le Francois - FRENCH MARTINIQUE (FR.) Algae bloom Coastline Other - Situation as of 06/07/2018 Algae deposit Transportation Polygon No. Area (ha) Coast affected (Km) 04 Delineation Map - MONIT06 General Information Primary Road Algae bloom 20 3.66 0 Caribbean Sea Area of Interest Secondary Road Algae deposit 47 19.51 2.04 La Trinite Caribbean Sea French Martinique Cartographic Information Image Footprint Local Road Total in AOI 67 23.17 2.04 (Fr.) ^ 1:33000 Full color ISO A1, high resolution (300 dpi) Not Analysed Cart Track Fort-de-France Fort-de-France Le François 05 Not Analysed - No data !( 0 0.5 1 2 ^ km Placenames Marin Grid: WGS 1984 UTM Zone 20N map coordinate system ! Placename 4.5 Tick marks: WGS 84 geographical coordinate system ± km 720000 722000 724000 726000 728000 730000 732000 734000 736000 0 60°57'0"W 60°56'0"W 60°55'0"W 60°54'0"W 60°53'0"W 60°52'0"W 60°51'0"W 60°50'0"W 60°49'0"W 60°48'0"W 0 N 0 0 " 0 0 0 ' 8 8 3 4 2 2 ° 6 6 4 1 1 1 Spot-7 (06/07/2018 14:15 UTC) N " 0 ' 2 4 N ° " 4 0 ' 1 0 0 2 4 0 0 ° 0 0 4 1 6 6 2 2 6 6 1 1 N " 0 ' 1 4 N ° " 4 0 ' 1 1 4 ° 4 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 4 2 2 6 6 1 1 Le Robert ! N " 0 ' 0 4 N ° " 4 0 ' 1 0 4 ° 4 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 2 6 6 1 1 N " 0 ' 9 3 N ° " 4 0 ' 1 9 3 ° 4 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 6 6 1 1 N " 0 ' 8 3 N ° " 4 0 ' 1 8 3 ° 4 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 1 1 6 6 1 1 N " 0 ' 7 3 N ° " 4 0 ' 1 7 3 ° 4 1 ! Le François 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 6 1 1 6 6 1 1 N " 0 ' 6 3 N ° " 4 0 ' 1 6 3 ° 4 1 0 0 -

Recommendation 3 ISO Country Code for Representation of Names of Countries

Recommendation 3 ISO COUNTRY CODE for Representation of Names of Countries At its first session, held in January 1972, the Group of The Working Party on Facilitation of International Trade Experts on Automatic Data Processing and Coding de- Procedures, cided to include in its programme of work the following Being aware of the need of an internationally agreed code task: system to represent names of countries, “To define requirements for country codes for use in Considering the International Standard ISO 3166 “Codes international trade, to be forwarded to ISO and to be for the representation of names of countries” as a suitable pursued in co-operation with it”. basis for application in international trade, It was entrusted to the secretariat to pursue this task. Recommends that the two-letter alphabetic code referred to in the International Standard ISO 3166 as “ISO AL- At a Meeting of the relevant ISO body, Working Group 2 PHA-2 Country Code”, should be used for representing of Technical Committee 46 “Documentation” in April the names of countries for purposes of International Trade 1972, it was agreed to set up a Co-ordination Committee whenever there is a need for a coded alphabetical desig- with the task to prepare proposals regarding a list of nation; entities, candidate numerical and alphabetical codes and maintenance arrangements. This Committee was com- Invites the secretariat to inform the appropriate ISO body posed of one representative each from ISO and ITU and responsible for the maintenance of ISO 3166 of any of the UNCTAD Trade Facilitation Adviser. amendments which the Working Party may suggest.