De Profundis-Mauthausen Memoir [PDF]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States V

American University International Law Review Volume 12 | Issue 1 Article 3 1997 Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States v. Lindert K. Lesli Ligomer Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Ligorner, K. Lesli. "Nazi Concentration Camp Guard Service Equals "Good Moral Character"?: United States v. Lindert." American University International Law Review 12, no. 1 (1997): 145-193. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMP GUARD SERVICE EQUALS "GOODMORAL CHARACTER"?: UNITED STATES V. LINDERT By K Lesli Ligorner Fetching the newspaper from your porch, you look up and wave at your elderly neighbor across the street. This quiet man emigrated to the United States from Europe in the 1950s. Upon scanning the newspaper, you discover his picture on the front page and a story revealing that he guarded a notorious Nazi concen- tration camp. How would you react if you knew that this neighbor became a natu- ralized citizen in 1962 and that naturalization requires "good moral character"? The systematic persecution and destruction of innocent peoples from 1933 until 1945 remains a dark chapter in the annals of twentieth century history. Though the War Crimes Trials at Nilnberg' occurred over fifty years ago, the search for those who participated in Nazi-sponsored persecution has not ended. -

Systematic Prejudice Against Jews. ∙Aryan: in the Na

Night Vocabulary/ Historical References ∙AntiSemitism: Systematic prejudice against Jews. ∙Aryan: In the Nazi ideology, the pure, superior Germanic (Nordic, Caucasian) race. ∙Auschwitz (Birkenau, Buna, and Gleiwitz): Concentration camp and extermination camp in Upper Silesia, Poland. By 1942, it consisted of three sections: Auschwitz I, the main camp; Birkenau, an extermination camp; and Buna, a labor camp. Gleiwitz was a subcamp in Auschwitz. ∙Beethoven, Ludwig van: German composer (17701827). Linked only to the Holocaust by race and the fact that Jews were forbidden to play the music of German composers. ∙Buchenwald: Concentration camp in Germany, between Frankfurt and Leipzig. Although not a major extermination center, it was equipped with gas chambers and a crematorium. More than 100,000 prisoners died there. ∙Concentration camp: Immediately upon their assumption of power on January 30, 1933, the Nazis established concentration camps for the imprisonment of all "enemies" of their regime: actual and potential political opponents (e.g. communists, socialists, monarchists), Jehovah's Witnesses, gypsies, homosexuals, and other "asocials." Beginning in 1938, Jews were targeted for internment solely because they were Jews. Before then, only Jews who fit one of the earlier categories were interned in camps. The first three concentration camps established were Dachau (near Munich), Buchenwald (near Weimar) and Sachsenhausen (near Berlin). ∙Crematory: The place that contained the ovens, furnaces, and chimneys where Nazi victims were burned dead or alive. ∙Death camp: A concentration camp, the distinct purpose of which was the extermination of its inmates. Almost all of the German death camps were located in Poland: AuschwitzBirkenau, Belzek, Chelmo, Madjanek, Sobibor, Treblinka. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/55w5n00s Journal AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW, 122(1) ISSN 0002-8762 Author Marcuse, Harold Publication Date 2017-02-01 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California June 28, 2016 Harold Marcuse, Featured Review for American Historical Review, of: KL: A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps, by Nikolaus Wachsmann, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 865 pp., cloth $40. review: 2574 words with 130 struck through = 2444 (2500 max) The title of this prodigious but eminently readable work, KL, is programmatic. Instead of the more commonly known and used abbreviation for the German Konzentrationslager, KZ, Nikolaus Wachsmann has chosen the official Nazi abbreviation, which was guarded like a trademark by the system's potentate, Heinrich Himmler, who did not want competing camps outside of his system. "KL" reflects Wachsmann's attempt to roll back the veils of historiography and memory to reveal the system as seen by its contemporaries as it unfolded over time. This undertaking synthesizes numerous works of German scholarship, which since the 1990s have drawn upon a wealth of newly available sources to shed light on many aspects of the Nazi camp system. While a meticulous and innovative overview of the Nazi concentration camp system based on the latest scholarly research would already be a significant achievement, Wachsmann combines this scholarship with an encyclopedic knowledge of published and unpublished survivor accounts. -

Secondary Source Information

Secondary Source Information From 1941 to 1945, German authorities transferred thousands of Lodz ghetto Jews to a number of forced labor and concentration camps and deported over 100,000 Jews from the Lodz ghetto to their deaths at the Chelmno and Auschwitz-Birkenau killing centers. The timeline and general histories below may provide valuable clues about specific camps and transports that included Jewish prisoners from the Lodz ghetto. TIMELINE OF TRANSPORTS INCLUDING LODZ GHETTO JEWS FEBRUARY 1940 – AUGUST 1944 ¾ Forced Labor Camps ¾ Chelmno ¾ Auschwitz AUGUST 1944 – MAY 1945 ¾ Bergen-Belsen ¾ Buchenwald ¾ Dachau ¾ Flossenbürg ¾ Gross-Rosen ¾ Mauthausen ¾ Natzweiler-Struthof ¾ Neuengamme ¾ Sachsenhausen ¾ Stutthof TIMELINE: Transports & Prisoner Registrations of Lodz ghetto Jews Size of Assigned Date Event From To Transport(s) Prisoner #'s Comments - 1942 - 14 Transports; Killed Jan. 16-29 Deportation Lodz Chelmno More than 10,000 in gas vans Approximately Feb. 22-28 Deportation Lodz Chelmno 7,025 Killed in gas vans March (daily) Deportation Lodz Chelmno More than 24,650 Killed in gas vans Approximately April 1-2 Deportation Lodz Chelmno 2,350 Killed in gas vans May 4-15 Deportation Lodz Chelmno More than 10,900 Killed in gas vans 298 people registered May 14 Arrival Lodz Auschwitz unknown 35363-35660 as prisoners 22 people registered July 15 Arrival Lodz Auschwitz unknown 46938-46959 as prisoners 19 people registered July 16 Arrival Lodz Auschwitz unknown 8726-8744 as prisoners Killed in gas vans; predominantly children under age 10, the elderly and Sept. 5-12 Deportation Lodz Chelmno More than 15,675 sick. 67759-67801, 43 men admitted, 19 Oct. -

Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe Symposium Presentations W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Forced and Slave Labor in Nazi-Dominated Europe Symposium Presentations CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2004 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, April 2004 Copyright © 2004 by Peter Hayes, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Michael Thad Allen, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Paul Jaskot, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Wolf Gruner, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Christopher R. Browning, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by William Rosenzweig, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Andrej Angrick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Sarah B. Farmer, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2004 by Rolf Keller, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................i -

An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps

Chaos, Coercion, and Organized Resistance; An Organizational Analysis of the Nazi Concentration Camps DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Thomas Vernon Maher Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. J. Craig Jenkins, Co-Advisor Dr. Vincent Roscigno, Co-Advisor Dr. Andrew W. Martin Copyright by Thomas V. Maher 2013 Abstract Research on organizations and bureaucracy has focused extensively on issues of efficiency and economic production, but has had surprisingly little to say about power and chaos (see Perrow 1985; Clegg, Courpasson, and Phillips 2006), particularly in regard to decoupling, bureaucracy, or organized resistance. This dissertation adds to our understanding of power and resistance in coercive organizations by conducting an analysis of the Nazi concentration camp system and nineteen concentration camps within it. The concentration camps were highly repressive organizations, but, the fact that they behaved in familiar bureaucratic ways (Bauman 1989; Hilberg 2001) raises several questions; what were the bureaucratic rules and regulations of the camps, and why did they descend into chaos? How did power and coercion vary across camps? Finally, how did varying organizational, cultural and demographic factors link together to enable or deter resistance in the camps? In order address these questions, I draw on data collected from several sources including the Nuremberg trials, published and unpublished prisoner diaries, memoirs, and testimonies, as well as secondary material on the structure of the camp system, individual camp histories, and the resistance organizations within them. My primary sources of data are 249 Holocaust testimonies collected from three archives and content coded based on eight broad categories [arrival, labor, structure, guards, rules, abuse, culture, and resistance]. -

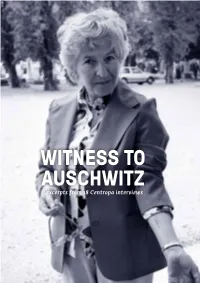

WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews

WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ excerpts from 18 Centropa interviews WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews As the most notorious death camp set up by the Nazis, the name Auschwitz is synonymous with fear, horror, and genocide. The camp was established in 1940 in the suburbs of Oswiecim, in German-occupied Poland, and later named Auschwitz by the Germans. Originally intended to be a concentration camp for Poles, by 1942 Auschwitz had a second function as the largest Nazi death camp and the main center for the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. Auschwitz was made up of over 40 camps and sub-camps, with three main sec- tions. The first main camp, Auschwitz I, was built around pre-war military bar- racks, and held between 15,000 and 20,000 prisoners at any time. Birkenau – also referred to as Auschwitz II – was the largest camp, holding over 90,000 prisoners and containing most of the infrastructure required for the mass murder of the Jewish prisoners. 90 percent of Auschwitz’s victims died at Birkenau, including the majority of the camp’s 75,000 Polish victims. Of those that were killed in Birkenau, nine out of ten of them were Jews. The SS also set up sub-camps designed to exploit the prisoners of Auschwitz for slave labor. The largest of these was Buna-Monowitz, which was established in 1942 on the premises of a synthetic rubber factory. It was later designated the headquarters and administrative center for all of Auschwitz’s sub-camps, and re-named Auschwitz III. All the camps were isolated from the outside world and surrounded by elec- trified barbed wire. -

Honors English 3-4. Your Summer Assignment Is to Complete the Following by the First Day of School 08/10/20 Whether You Do So Physically Or Virtually

Albert/English Albert/Plaa Honors English 3-4 Summer Assignment Directions Welcome to Honors English 3-4. Your summer assignment is to complete the following by the first day of school 08/10/20 whether you do so physically or virtually. The work itself is not difficult, but the subject matter is. Our first book is Night written by Elie Wiesel. The study of the Holocaust is an important and serious one and we expect our students to treat it with respect and solemnity. Your assignments are: 1. Read the speech by Heinrich Himmler and follow the directions on the last page. 2. Complete and fill out the vocabulary, term, people, places, etc. 3. You are to find a map like the one in the folder. Color and label each country. You are not to use a map that is pre-labeled. Place each camp in its country and color-code them by the number of deaths/population/type of camp/operation time. Which type you use is up to you. You may mix/match as long as each camp is labeled by its name clearly and notated by which identifier you used. a. A blank map is attached to the assignment. Any and all questions on assignments must be submitted to [email protected] and/or [email protected] before 08/09/20. Albert/Plaa Honors English 3-4 Summer Assignment 2/3 Except of a speech by Reichsfurher Heinrich Himmler justifying extermination, spoken to senior SS officers in Pozan, October 4, 1943. -

Visitors' Guide

Cincinnati SkirballMuseum inpartnership with The CenterforHolocaust andHumanity Education presents 12NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMPS: Photographs by James Friedman October 13, 2016—January 29, 2017 VISITORS’ GUIDE The FotoFocus Biennial 2016 is a regional, month-long celebration of photography and lens-based art held throughout Cincinnati and the surrounding region that features over 60 exhibitions and related programming. As part of the Biennial, participating venues respond to the theme: Photography, the Undocument. A FOTOFOCUS exhibition presented by the Cincinnati Skirball Museum of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in partnership with The Center for Holocaust and Humanity Education. Support for this exhibition was provided by Cover photo: Local resident with scythe and self-portrait, Auschwitz II (Birkenau) concentration camp, Oswiecim, Poland, 1983 ©James Friedman Cincinnati SkirballMuseum inpartnership with The CenterforHolocaust andHumanity Education presents 12NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMPS: Photographs by James Friedman PHOTOGRAPHER’S STATEMENT My pictures were created in color with a cumbersome 8” x 10” field camera. The expectation on the part of many viewers is that contemporary photographs of Nazi concentration camps should be in black and white and without people or reference to the contemporary world. My color photographs include self-portraits, tourists and survivors, and have inspired visceral responses in many viewers. My color photographs exist in stark contrast to the historical black and white photographic record of Holocaust images that are the basis for most viewers’ knowledge and understanding of the Nazi era. — James Friedman “James Friedman’s ’12 Nazi Concentration Camps’ is arguably the most significant body of photographic work on the concentration camps in the post-Holocaust era …” — Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnessing by Dora Apel, Ph.D. -

Forced Labour and Genocide: the Nazi Concentration Camp System During the War Jens-Christian Wagner

Forced Labour and Genocide: The Nazi Concentration Camp System during the War Jens-Christian Wagner In December 1943, the Hygiene Institute of the of a crematorium as soon as possible” (“in this Armed SS in Berlin sent the SS physician Dr Karl connection, sufficient incineration capacity is to Gross to inspect “Dora”, a Buchenwald subcamp be taken into consideration from the start”), and established a few months previously near the finally “the establishment of an alternative camp town of Nordhausen. The authorities in Berlin for inmates unable to work”. 2 were evidently alarmed by the unusually high death rate in the camp, whose inmates, in addi- Here the SS physician essentially summed up tion to performing forced labour underground, what had become decisive for the concentration also had their lodgings underground for the most camp system after its “economization” began part at that point in time. Gross had been as- in 1942: selection and segregation were key signed to get to the bottom of the problem. After interfaces between the two poles of labour and his visit, he wrote a detailed and presumably annihilation. Apart from positioning the inmates quite realistic report. “The severely and fatally on the racist ladder dictated by the SS, factors ill as well as the dying at their workplaces are of crucial importance in this context were the conspicuous”, Gross wrote, and on the whole inmates’ physical constitution and professional described the conditions in the underground con- qualifications as well as the nature of the work centration camp in the darkest colours. 1 they were assigned. -

Gross-Rosen Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°59¢57²N 16°16¢40²E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit Search Gross-Rosen concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°59¢57²N 16°16¢40²E Gross-Rosen Concentration Camp Main page (German: Konzentrationslager Groß-Rosen) Contents was a German concentration camp, located Featured content in Gross-Rosen, Lower Silesia (now Current events Rogoźnica, Poland). It was located directly Random article on the rail line between Jauer (now Jawor) Donate to Wikipedia and Striegau (now Strzegom). Interaction Contents [hide] Help 1 The camp About Wikipedia 1.1 Camp commandants Community portal 2 Notable inmates Recent changes 3 See also Contact Wikipedia 4 References Nazi concentration camps in occupied Toolbox 5 External links Poland (marked with black squares) Print/export The camp [edit] Languages Azrbaycanca It was set up in the summer of 1940 as a Català satellite camp to Sachsenhausen, and Česky became an independent camp on May 1, Dansk 1941. Initially, work was carried out in the Deutsch camp's huge stone quarry, owned by the SS- Ellhnik Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (SS Español German Earth and Stone Works). As the Esperanto complex grew, many inmates were put to Gross-Rosen entrance gate with the Français work in the construction of the subcamps' phrase Arbeit macht frei Hrvatski facilities. Italiano In October 1941 the SS transferred about 3,000 Soviet POWs to Gross-Rosen for Nederlands execution by shooting. Gross-Rosen was known for its brutal Polski treatment of NN (Nacht und Nebel) Русский prisoners, especially in the stone quarry. Српски / srpski The brutal treatment of the political and Suomi Jewish prisoners was not only due to the SS Svenska and criminal prisoners, but to a lesser extent Türkçe also due to German civilians working in the Gross-Rosen memorial Ting Vit stone quarry. -

HOLOCAUST DENIAL Kenneth S

HOLOCAUST DENIAL Kenneth S. Stern The American Jewish Committee New York Kenneth S. Stern is program specialist on anti-Semitism and extremism for the American Jewish Committee. The American Jewish Committeeprotects the rights andfreedoms ofJews the world over; combats bigotry and anti-Semitism andpromotes hwnan rights for all; works for the security of Israel and deepened understanding between Americans and Israe- lis; advocates public policy positions rooted in American democratic vulues and the perspectives ofthe Jewish heritagr: and enhances the creative virality of the Jewish people. Founded in 1906, it is the pioneer human-relations agency in the United States. Copyright 0 1993 The American Jewish Committeen All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog number 93-070665 ISBN 0-87495-102-X First printing April 1993 Second printing June 1993 Third printing July 1994 This publication is dedicated to the memory of Zachariah Shuster, who gave 40 years of extraordinary service to the cause of world Jewry, human rights, and Jewish-Christian understanding. He opened AJC's European office in 1948, helping thousands of Holo- caust survivors, and, later, North African Jews fleeing anti-Semi- tism, rebuild their lives. On behalf of the AJC, he had a hand in establishing the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, the passage of Nostra Aetaze-which marked a turning point in Catholic attitudes toward Jews-and the publication of German textbooks containing accurate information about Jews, Judaism, anti-Semitism, and the Holocaust. In the early 1950s, Zachariah Shuster was one of the first to speak out about the plight of Soviet Jewry.