Indianapolis Cultural Trail Indianapolis, Indiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monon Trail Indianapolis, In

Indiana Trails Study MONON TRAIL INDIANAPOLIS, IN November, 2001 Eppley Institute for Parks & Public Lands School of Health, Physical Education & Recreation HPER 133, Indiana University Bloomington, IN 47405 Acknowledgements Monon Trail Report Indiana Trails Study A Study of the Monon Trail in Indianapolis, Indiana Funded by Indiana Department of Transportation Indiana Department of Natural Resources National Park Service Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program Completed by Indiana University Eppley Institute for Parks & Public Lands Center for Urban Policy & the Environment Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis Stephen A. Wolter Dr. Greg Lindsey Project Director Research Director Project Associates John Drew Scott Hurst Shayne Galloway November 30, 2001 Indiana Trails Study City of Indianapolis Parks and Recreation The Indiana Trails Study could not have been accomplished without the support and cooperation of leaders and staff from the local trail organizations that participated in the study. The following individuals served as the primary contacts and provided assistance to the Trails Study Team and played an important role in facilitating the completion of this study: Bart Peterson Mayor City of Indianapolis Joseph Wynns Director Department of Parks and Recreation Ray R. Irvin Administrator DPR Greenways Annie Brown Admin. Assistant DPR Greenways Lori Gil Sr. Project Manager DPR Greenways Terri VanZant Sr. Project Manager DPR Greenways SonCheong Kuan Planner DPR Greenways Jonathon -

Culturaldistrict 2012 Layout 1

INDIANA INDIANA UNIVERSITY PUBLIC POLICY INSTITUTE PUBLIC POLICY RESEARCH FOR INDIANA JULY 2012 Indianapolis Cultural Trail sees thousands of users during Super Bowl The Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn data for the Indy Greenways trail network. PPI began counting Glick (Cultural Trail) started with a vision of an urban trail net- trail traffic at four locations along the Monon Trail in February work that would highlight the many culturally rich neighbor- 2001, and is currently monitoring a network of 19 locations on hoods and promote the walkability of the city of Indianapolis. seven trails in Indianapolis including the Monon, Fall Creek, Based upon the success of the Monon Trail and the Indy Canal Towpath, Eagle Creek, White River, Pennsy, and Pleasant Greenways system, the Cultural Trail was designed to connect the Run trails. There were two primary goals for setting up counters five Indianapolis cultural districts (the Wholesale District, Indiana along the Cultural Trail: first, to show the benefit and potential Avenue, the Canal & White River State Park, Fountain Square, uses of trail data, and second, to analyze the impact of a large and Mass Ave) and Broad Ripple Village. While each cultural dis- downtown event like the Super Bowl. trict exhibits unique characteristics and offers much to visitors This report presents data collected at two points along the and residents alike, connecting the districts offers greater poten- Cultural Trail (Alabama Street and Glick Peace Walk) during a tial to leverage the cities’ assets and promote its walkability. The three-week period around the 2012 Super Bowl festivities. -

Downtown Indianapolis

DOWNTOWN INDIANAPOLIS Martin Luther King Memorial Park 17th St. INTERSTATE MARTINDALE HERRON BRIGHTWOOD 65 MORTON 16th St. 16th St . 16th St. Fall Creek L 15th St. 15th St. I , o g a c 14th St. 14th St. i . h . C ve. INTERSTATE 13th St. 13th St. KENNEDY KING 70 Benjamin Morris-Butler Meridian St. Pennsylvania St. Pennsylvania Delaware St Delaware Capitol Ave. Illinois St Illinois Central A Central Alabama St. Alabama 16 TECH Senate Ave. Harrison OLD NORTHSIDE House H College Ave. College O Presidential , Dr. Martin Luther King St. Dr. NEAR s u l b i NORTH 12th St. Site 12th St. lum CRISPUS ATTUCKS Co onon Tra INTERSTATE Monon Trail M WINDSOR PARK Crispus Attucks Museum 65 11th St. 11th St. HAUGHVILLE P 10th St. 10th St. h St. 10t Central Canal P ST. JOSEPH ST. Indiana Ave. CHATHAM ARCH RANSOM PLACE 9th St. Central Library P St. Clair St . yne Ave. P Madame Riley Hospital Walker Fort Wa for Children Walnut St. Theatre Center American Walnut St. Legion P Mall Scottish P Rite COTTAGE HOME Cathedral North St. IU Health North St. University Hospital Veterans Old Memorial National P Plaza Centre Blake St. Michigan St. Michigan St. Michigan St. P P Indiana P World Indiana University War Massachusetts Ave. HOLY CROSS Purdue University Memorial Vermont St. P LOCKERBIE Vermont St. Indianapolis Courtyard SQUARE by Marriott University P Meridian St. West St. West Pennsylvania St. Delaware St. East St. College Ave. Senate Ave. Capitol Ave. Illinois St. New Jersey St. Residence Alabama St. (IUPUI) Inn by Park Blackford St. -

Architectural Significance

Historic Significance Photo Source: Vegetable Market on Delaware Street, 1905, Indiana Historical Society Collection 33 Monument Circle District Preservation Plan 34 Monument Circle District Preservation Plan HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE City Planning and Development Carved out of the Northwest Territory, Indiana entered the Union as the nineteenth state in 1816. The city of Indianapolis was founded in 1821 as the state capital, when the Indiana State Legisla- ture sought a central location for the city and appointed a committee to choose the site. Once the site was chosen surveyors Alexander Ralston and Elias Fordham were hired to lay out the city, which was proposed as a grid of north-south and east-west streets in a mile square plat. This plat was influenced by the Pierre L’Enfant plan for Washington, D.C., which in turn was in- spired by the royal residence of Versailles. Since Indianapolis was planned as a state capital, the plat sited the State House Square and the Court House Square equidistant from Circle Street (now Monument Circle), located in the center of the Mile Square. The Governor’s house was to be situ- ated in the circular lot framed by Circle Street, and the four city blocks framing the Circle were known as the “Governor’s Square.” Four diagonal streets radiated out from the far corners of the four blocks framing the circle. All streets of the Mile Square were 90 feet wide with the exception of Washington Street, which was 120 feet wide to accommodate its intended use as the capital’s main street. The sale of lots in the new capital city on October 8, 1821 reveal the street’s importance, as lots fronting it com- manded the highest prices. -

Holliday Park Regional Connectivity

HOLLIDAY PARK REGIONAL CONNECTIVITY Monon Trail to Holliday Park 75th Street Hamilton County: 2.75 Miles is one of four unique cultural Meridian Hills/Williams Creek resources and open spaces that Ravenswood share the White River reaches up Northtown Trail to Eagle Creek 1 MILE and downriver from the Broad Park: 8 Miles RADIUS Ripple dam: Holliday Park, Northtown Trail to Marott Park Nature Preserve, Fort Harrison State Park: 6 Miles the Indianapolis Art Center and College Avenue 71st Street 71st Street White River Broad Ripple Park. All close Marott geographically but far apart in Meridian Hills Arden Park County Club Delaware Nature connectivity. Preserve Trails 0.5 MILE RADIUS North Central They aren’t well connected either Indianapolis Art Center in our minds’ mental maps or by 67th St. Link our conveyances, whether those Red Line are our feet, our bicycles [or our Bus Rapid Transit cars for that matter]. Levee Trail Station Broad Blickman Educational Trail Ripple W 64th Street Link Monon Trail Village E 64th Street Link How can these complementary W 64th Street Broad resources be more easily accessed River Ripple Canal White River from nearby neighborhoods Holliday E 63rd Street Link Red Line Monon Oxbow Park Bus Rapid Crossing Park Transit Station Esplanade without increasing traffic, parking White Broad Ripple Ave RiverWalk Phase 1a Warfleigh impacts and by providing healthy, Levee Trail RiverWalk Phase 1b: Spring Mill Road 0.56 miles to Glendale active connections? Broad Ripple Meridian Street Connectivity Project Mission Identify and envision physical Winthrop Compton Primrose North College Avenue projects that will better connect Holliday Park to the surrounding Kessler Boulevard neighborhoods and broader Indianapolis community, 58th Street specifically focusing on the White River Corridor. -

Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: a Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick

Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick 334 N. Senate Avenue, Suite 300 Indianapolis, IN 46204 Assessment of the Impact of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick March 2015 15-C02 Authors List of Tables .......................................................................................................................... iii Jessica Majors List of Maps ............................................................................................................................ iii Graduate Assistant List of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv IU Public Policy Institute Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 Key findings ....................................................................................................................... 1 Sue Burow An eye on the future .......................................................................................................... 2 Senior Policy Analyst Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3 IU Public Policy Institute Background ....................................................................................................................... 3 Measuring the Use of the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene -

Reasons to Love the Indianapolis Cultural Trail

Reasons to Love the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick The Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn The Indianapolis Cultural Trail is having a Glick (the Trail) is an eight-mile urban bike and pedestrian measurable economic impact. pathway that serves as a linear park in the core of downtown Property values within 500 feet (approximately one block) Indianapolis. Originally conceived by Brian Payne, Presi- of the Trail have increased 148% from 2008 to 2014, an dent and CEO of the Central Indiana Community Foundation increase of $1 billion in assessed property value. (CICF), to help create and spur development in the city’s cultural districts, the Trail provides a beautiful connection for residents and visitors to safely explore downtown. Com- many businesses along Massachusetts and Virginia Avenues.The Trail Businesshas increased surveys revenue reported and part-timecustomer andtraffic full-time for cultural districts and provides a connection to the seventh via jobs have been added due to the increases in revenue and pleted in 2012, the Trail connects the now six (originally five) - tural, heritage, sports, and entertainment venue in downtown Indianapolisthe Monon Trail. as well The as Trail vibrant connects downtown every significantneighborhoods. arts, cul customers in just the first year. It also serves as the downtown hub for the central Indiana expenditure for all users is $53, and for users from outside greenway system. theUsers Indianapolis are spending area while the averageon the Trail. exceeds The $100.average In all,expected Trail users contributed millions of dollars in local spending. -

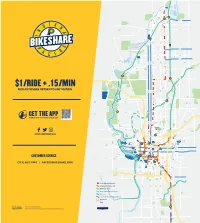

Get Theapp Mobile Map and Bikecheck out Customer Service @Pacersbikeshare | Pacersbikeshare.Org 0

E 71ST ST. Marott Park Indianapolis Art Center Opti Park 66TH ST. RIVERVIEW DR. WESTFIELD BLVD. N MERIDIAN ST. 65TH ST. er 64TH ST. v White Ri WASHINGTON BLVD. CENTRAL AVE. Holliday Park White Rive Broad Ripple Park r BROAD RIPPLE AVE. WINTHROP AVE. WINTHROP GUILFORD AVE. GUILFORD COLLEGE AVE. BROAD RIPPLE AVE. RIVERVIEW DR. E 63RD ST. WESTFIELD BLVD. Monon Trail Monon Juan Solomon Park N MERIDIAN ST. E 61ST ST. E 61ST ST. Dan Wakefield Park INDYGO RED LINE BUS RAPID TRANSIT KESSLER BLVD E DR. KESSLER BLVD E DR. KESSLER BLVD E DR. Friedman Park N MERIDIAN ST. MERIDIAN N WESTFIELD BLVD. The Riviera Club Monon Trail Monon Canterbury 56TH ST. Park WINTHROP AVE. GUILFORD AVE. COLLEGE AVE. CENTRAL AVE. MERIDIAN ST. ILLINOIS ST. N CAPITOL AVE. er White Riv 54TH ST. 54TH ST. Highland Golf Country Club WESTFIELD BLVD.54TH ST. Rocky Ripple 52ND ST. 52ND ST. 52ND ST. Holcomb Gardens E 49TH ST. 49TH ST E 49TH ST. Butler Arsenal Park University AVE. SUNSET Central Canal Trail E 46TH ST. E 46TH ST. MICHIGAN RD. COLLEGE AVE. CENTRAL AVE. MERIDIAN ST. COLD SPRING RD. N CAPITOL AVE. ILLINOIS ST. EVAANSTON AVE. HAMPTION DR. HAUGHEY AVE. HAUGHEY INDYGORED LINEBUS RAPID TRANSIT 43RD ST. 43RD ST. Andrew COLD SPRING RD. Ramsey Park E 42ND ST. E 42ND ST. Central Canal Trail Monon Trail MICHIGAN RD. 42ND ST. Tarkington Park Crown Hill Cemetary Fall Creek Trail Newfields 38TH ST. 38TH ST. INDYGO RED LINE BUS RAPID TRANSIT 38TH ST. Watson Road Bird Preserve Woodstock Riverside Country Club Golf Academy Lake Sullivan Sports Complex & E FALL CREEK PKWY DR. -

Near Eastside Neighborhood Indianapolis, in Baseline Report: May 2011

LISC Sustainable Communities Initiative Neighborhood Quality Monitoring Report Near Eastside Neighborhood Indianapolis, IN Baseline Report: May 2011 Original Version: September 2010 Revisions: April 2014 Near Eastside Neighborhood Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 COMMUNITY QUALITY AND SAFETY ................................................................... 20-28 MAP OF NEIGHBORHOOD LOCATION ................................................................. 4 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................. 20 GENERAL DEMOGRAPHICS ................................................................................... 5-7 ALL PART 1 CRIMES .............................................................................................. 21 OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................ 5 ALL PART 1 CRIMES BY TYPE ................................................................................ 22 AGE ....................................................................................................................... 6 VIOLENT CRIMES .................................................................................................... 23 RACE, ETHNICITY, EDUCATION, AND INCOME....................................................... 7 PROPERTY CRIMES ............................................................................................... -

Property Flyer

EMRICH PLAZA RETAIL SHOPS 324 W MORRIS STREET, INDIANAPOLIS, IN 46225 rcre.com LEASE RETAIL RESTAURANT HIGH-TRAFFIC RETAIL / RESTAURANT SPACE CLOSE TO DOWNTOWN INDY LEASE RATE AVAILABLE SF NEGOTIABLE 750 - 7,700 SF Just south of downtown Indianapolis and 0.5 mile from Lucas Oil Stadium, this unique 15,000 SF restaurant/retail property is located on the Northeast corner of Missouri St and W Morris St. The restaurant and retail space is adjacent to a new Marathon Gas Station/ Convenience Store that will generate significant traffic to the site. The center will include a 1,000 SF communal indoor/outdoor patio. This location has great visibility and access from I-70 which carries more than 94,000 vehicles per day. In total, there are over 3,400 businesses within 1.5 miles that employ over 87,000 people, providing high daytime demographics. Some of the region's largest employers are located with easy access to 324 West Morris, including: • Eli Lilly • State of Indiana Government Center and State House • Anthem • Simon Property Group • Cummins • IU Health/Riley Hospital for Children • IUPUI • NCAA Headquarters #growIndiana PATRICK O'HARA Vice President of Retail Services O 317.663.6076 C 317.796.4733 [email protected] EXECUTIVE SUMMARY LEASE RETAIL EMRICH PLAZA RETAIL SHOPS 324 W MORRIS STREET, INDIANAPOLIS, IN 46225 OFFERING SUMMARY LOCATION OVERVIEW The surrounding area is home to multiple major traffic drivers that help generate more than 26 million visitors to Downtown Indianapolis every year. Those attractions include: Lease Rate: Negotiable -

Library Board Meeting Agenda

Library Board Meeting Agenda Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library Notice Of The Regular Meeting November 27, 2017 Library Board Members Are Hereby Notified That The Regular Meeting Of The Board Will Be Held At The Library Services Center 2450 North Meridian Street At 6:30 P.M. For The Purpose Of Considering The Following Agenda Items Dated This 22nd Day Of November, 2017 DR. DAVID W. WANTZ President of the Library Board -- Regular Meeting Agenda -- 1. Call to Order 2. Roll Call Library Board Meeting Agenda pg. 2 3. Presentation on IndyPL Outreach Services – Sharon Bernhardt, Interim Outreach Manager, will make the presentation. (at meeting) 4. Public Comment and Communications a. Public Comment The Public has been invited to the Board Meeting. Hearing of petitions to the Board by Individuals or Delegations. Only one may speak for a delegation on an issue. Speakers who wish to address an item on the Agenda will be called at the appropriate time during the meeting. A five-minute limit will be allowed for each speaker. b. Dear CEO Letters and Responses (at meeting) c. Correspondence for the Board's general information. (at meeting) 5. Approval of Minutes a. Executive Session, October 23, 2017 (enclosed) b. Regular Meeting, October 23, 2017 (enclosed) COMMITTEE REPORTS 6. Finance Committee (Dr. Terri Jett, Chair; Lillian L. Charleston, Joanne M. Sanders) a. Report of the Treasurer – October 2017 (enclosed) b. Briefing Report – Fines, Fees and Charges for 2018 (enclosed) c. Briefing Report – 2018 D & O Entity Liability and Employment Practices Liability (enclosed) Library Board Meeting Agenda pg. 3 d. -

INDY GREENWAYS the Indy Greenways Patch Is a Local Patch Program That Teaches Central Indiana Girl Scouts About the Indy Greenways System

INDY GREENWAYS The Indy Greenways patch is a local patch program that teaches central Indiana Girl Scouts about the Indy Greenways system. The intent of the program is to raise awareness and educate young kids on the design, function, and proper use of the Indy Greenways and to demonstrate the important role that the greenways play in connecting local communities. It is also intended to instill a level of ownership, responsibility, and stewardship for the greenway system. The patch program aims to achieve the following objectives: Raise awareness of the Indy Greenways system, what it is, and how it is used. Provide a basic understanding of Indy Greenways and how to use the trails. Provide a basic understand of how trails and greenways benefit communities. Instill a responsibility for the ongoing stewardship of the greenways system. Instill a general interest on how the greenways can be a part of Girl Scouts’ everyday lives. Getting Started This program has been developed to accommodate multiple age levels of girl scout troops, with specific focus on the following grade levels: • Girl Scout Daisies, Brownies and Juniors - grades K-5. • Girl Scout Cadettes- grades 6-8. Troop leaders should modify the program as needed to accommodate specific troop age and grade levels. Program Overview The program includes three basic elements that must be completed in order to achieve the Indy Greenways patch: Learn Indy Greenways (Educational Component) - a troop- facilitated educational session that introduces Indy Greenways, its purpose, and other important facts about the greenways and their use. The educational component includes research and discussion that can be led by volunteer troop leaders and can be completed within an one-hour working session (troop meeting).