Re.Port Resumes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 15, 2021 Norman Mundy, Environmental Supervisor II Los

February 15, 2021 Norman Mundy, Environmental Supervisor II Los Angeles Bureau of Engineering, Environmental Management Group 1149 S. Broadway, Suite 600, Mail Stop 939 Los Angeles, CA 90015 Re: Los Angeles Zoo Vision Plan Project Draft Environmental Impact Report SCH# 2019011053 Public parks are a safety valve of great cities and should be made accessible and attractive, where neither race nor creed nor color should be excluded….Give nature a chance to do her good work and nature will give every person a greater strength in health, strength and mental power. Griffith J. Griffith Dear Mr. Mundy, Friends of Griffith Park, the advocacy group for all of Griffith Park, has carefully reviewed the Los Angeles Zoo Vision Plan Project Draft Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) released in December 2020. We have numerous concerns regarding the scope of the proposed project and the loss of Open Space that would result. Loss of Open Space / Connectivity The Zoo, although an independent city department, is located entirely within the boundaries of Griffith Park. It is not “zoo property” as claimed in several places throughout the DEIR. Friends deplores the DEIR’s description of open space as “underutilized and underdeveloped areas” (ES-3 and 2-30). Our Indigenous populations tread lightly on the land and had great respect and reverence for the native habitat; they did not consider it “underutilized.” Griffith J. Griffith, who donated the land to the city for a park, certainly knew the value of open space and nature. (Above quote) Los Angeles County designated Griffith Park a Significant Ecological Area (SEA) forming “an extensive, relatively undisturbed island of natural vegetation in an urbanized, metropolitan area.” This Open Space currently provides invaluable habitat for the native flora and fauna that call Griffith Park home. -

Vol. 29 No. 06 February 1963

Los Angeles AucLubon Society The Western Tanager VOLUME 29 FEBRUARY 1963 NUMBER 6 CHRISTMAS COUNTDOWN-1962 LOS ANGELES AUDUflON SOCIETY, INC. PLUMMER PARK 7377 SANTA MONICA BLVD. By HUGH KINGERY LOS ANGELES 46, CALIFORNIA The downtown parks, Echo and MacArthur Parks, present excellent places to observe water- fowl, and Elysian Park has a surprising variety If finaL totals for the 1962 Christmas Bird of land birds. Twenty observers were counting Census were: 135 species, 27,060 individuals. in Griffith Park and their diligence shows in the This is three fewer species than last year (the large numbers recorded from there. One pheno- same number as I960), bat twice the number of menal total which came out of the Census was the individuals. It is, in fact, the largest number of huge number of birds tallied by observers at home individual birds recorded since 1958. The reason watching their feeders, yards or neighborhood. for this is simply--more observers; we had 107 These watchers counted 38 species, 2167 indivi- participants this year, 45 last year. duals, including three species not found otherwise in the city. Among the more striking observations were: We noted these trends from the Census: 505 Anna's Hummingbirds—180 more than we scarcity of Robins and Thrushes so far this year; have ever recorded (perhaps due to more feeders no Bluebirds (all this despite & bumper crop of plus the mild winter), & Bald Eagle over Echo berries in the chaparral); Herons and Egrets dis- Park, a Swainson's Thrush in Elysian Park, one appearing along with their habitat; Coots and Hooded Oriole and four Western Tanagers attend- 3horebirds, Western Gulls and Savannah Sparrows ing feeders, and a Black-headed Grosbeak in decreasing for the same reason; the Sparrow Hawk, Griffith Park. -

Audit-2018-LA-Zoo.Pdf

April 25, 2018 Honorable Eric Garcetti, Mayor Honorable Michael Feuer, City Attorney Honorable Members of the Los Angeles City Council Re: Review of the Zoo Department and GLAZA The Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens (Zoo) is an important cultural, educational and recreational institution of our City. To help the Zoo best realize its potential, my Office conducted a Review of the Governance Arrangement between the City’s Zoo Department and the not-for-profit Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association (GLAZA). The Review includes recommendations for near-term and long-term changes to propel the Zoo forward. The Zoo’s mission is to serve Angelenos and visitors by creating a place for recreation and discovery, for inspiring an appreciation for wildlife through exhibitry and education, and for animal welfare. The mission also includes supporting programs that preserve biodiversity and conserve natural habitat. The Zoo has been nationally recognized for its achievement despite staffing shortages, infrastructure challenges and budget limitations. GLAZA, the independent not-for-profit corporation and official support organization of the Zoo, is made up of paid staff and a volunteer board that have been dedicated to managing membership, concessions, fundraising and marketing. The governance arrangement in which the City’s Zoo Department and GLAZA share responsibilities defined by an operating agreement and multiple Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs), has become cumbersome, however, for all parties involved. The result has often led to confusion and difficulty in fully achieving accountability and transparency. In the near-term, steps should be taken to reduce the confusion and increase accountability. In the longer-term, it is time for the City to explore a new organizational model to make the Zoo the world class entity it can be - and that Angelenos deserve. -

Exploring L.A.'S Hidden Treasures Discover

CURRENTS Off campus: Where three students are making their mark Exploring L.A.’s ahidden look at five treasures secret spots buried in the urban jungle Dine and Loud Clear: one athlete’s determination& to Discover:two restaurants rising in popularity speak for a muted community a letterfrom the editors Today is the day to discover something new. Or perhaps, to rediscover something lost. It’s all too easy to lose our keys or ID card or even what we’re passionate about. Small aspects of our lives and aspirations become buried over the years, hidden underneath the monotony of routine. So, it’s time to grab your shovel and dig. What exactly are we looking for? Well, hidden treasure of course. It’s time to dig under- neath the surface of the urban jungle and treat it for what it truly is: an adventure. We’re surrounded with beautiful gems just out of sight and untold stories just one more layer deep. They’re not easy to uncover, but the adventure is what makes buried treasure so fun to find. The captivating beauty of the bright city lights and miles of sandy shoreline are not all that this city offers. It’s time to diverge from PCH and forge a road not yet traveled. Google maps can’t take you where we’re going — only a hand-crafted treasure map can. Lucky for you, it’s in your hand. And what better guide than Indiana Jones? College is more than four years behind a desk; it’s a journey. -

Written Historical and Descriptive Data Hals Ca-105

GRIFFITH PARK ZOO HALS CA-105 4730 Crystal Springs Drive HALS CA-105 Los Angeles Los Angeles County California WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN LANDSCAPES SURVEY GRIFFITH PARK ZOO (Old Zoo) HALS NO. CA-105 Location: Griffith Park, 4730 Crystal Springs Drive, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, California. Latitude: 34.133970 Longitude: -118.288494 (center of picnic area, iTouchMaps.com) Griffith Park is a 4,310 acre, Los Angeles city park in the Los Feliz area of Los Angeles, California. The park is located 6 miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles, at the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains. The north and east borders of the park are adjacent to the 134 Freeway (Ventura), and the 5 Freeway (Golden State). The south border is Los Feliz Boulevard, but including the Municipal Plunge and playground, south of the boulevard, and to the west are the residences of the Los Feliz and the Hollywood Hills areas. Significance: Griffith Park is Los Angeles Historic Cultural Monument No. 942, adopted on January 27, 2009. Colonel Griffith J. Griffith donated the 3,015-acre property to the City of Los Angeles in 1896, and still it remains the largest private land gift for Los Angeles, and has mostly an untouched landscape in the center of an urban metropolis. Large portions of this landscape appear to retain integrity dating back to the period of native American land use. Within the park are some of the city’s most iconic treasures – Griffith Observatory and the Hollywood Sign, also Historic Cultural Monuments, as well as the Feliz Adobe, and a Gabrielino Indian site.1 Griffith Park Zoo (Old Zoo) was built in 1913, and is “inset at the north-facing base of hills forming Spring Canyon, below Old Zoo Trail.”2 The zoo closed in 1966 with the opening of the Los Angeles Zoo. -

3.11 Land Use and Planning

3.11 Land Use and Planning 3.11 LAND USE AND PLANNING The Project would guide transformation of the Zoo as an environmentally sustainable, world-class destination for animal care and wildlife conservation. The Project includes a conceptual land use and development plan that covers the main physical aspects of the Zoo, including animal conservation environments, visitor-serving uses, administration and service buildings, pedestrian circulation, infrastructure improvements, and the entry and access/parking. The Project would be consistent with regional and local plans, including the City General Plan and North Hollywood Community Plan. This section evaluates the consistency of the proposed Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens (Zoo) Vision Plan (Project) with existing plans and land use designations, including applicable goals, programs, and policies in the City of Los Angeles (City) General Plan, as well as regional plans and related planning policy documents. 3.11.1 Environmental Setting Regulatory Setting This section summarizes directly relevant state regulations and regional and local land use plans and procedures. There are no federal regulations that would apply to land use and planning of the Project and surrounding areas. Evaluation of the Project’s consistency with specific goals, policies, and requirements from relevant land use plans and regulations is provided below in Section 3.11.3, Environmental Impact Analysis, as well as within referenced EIR sections, including Section 3.8, Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Section 3.15, Transportation. State Regulations Southern California Association of Governments Regional Comprehensive Plan The Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG) is a Joint Powers Authority (JPA) under California state law, established as an association of local governments and agencies that voluntarily convene as a forum to address regional issues. -

LA's Next Frontier

LA’s Next Frontier: Capturing Opportunities for New Housing, Economic Growth, and Sustainable Development in LA River Communities The Taylor Yards Crossing Community Bridge, proposed by Studio Pali Fekete architects [SPF:a] 2 3 About Us The LABC Institute is a forward-thinking research and education organization dedicated to strengthening the sustainable economy of California, particularly the Southern California region. Founded in 2010, the LABC Institute provides a bridge between the business, government, environmental, labor and nonprofit communities of Southern California to develop policies and programs that promote investment, jobs and business development. We are the research and education arm of the Los Angeles Business Council, one of the most respected business advocacy organizations in Southern California. A Coordinated Approach The LABC Institute collaborates with diverse community stakeholders and world class institutions – USC, UCLA, CalTech and others – to conduct research leading to policies and programs that help build healthy communities. Our research focuses on environmental and sustainability best practices that also promote investment and economic development in Southern California. The results of our research influence a broad range of leaders – including governmental officials, business executives, journalists and directors of community-based organizations – who engage with our work in informal settings and at Institute-sponsored summits, conferences and forums that help shape the public policy agenda. Achieving Measureable Results The LABC Institute’s ground-breaking research on new energy policies has earned national recognition. Our innovative work on rooftop solar energy options led directly to the implementation of the Feed-in Tariff program, adopted in the spring of 2012 by the City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. -

Registered Events

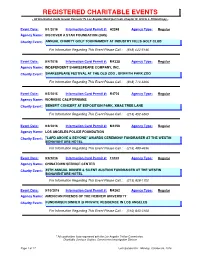

REGISTERED CHARITABLE EVENTS - All Information Cards Issued, Pursuant To Los Angeles Municipal Code, Chapter IV, Article 4, Philanthropy - Event Date: 9/1/2016 Information Card Permit #: A2248 Agency Type: Regular Agency Name: DISCOVER A STAR FOUNDATION (DAS) Charity Event: ANNUAL CHARITY GOLF TOURNAMENT AT INDUSTRY HILLS GOLF CLUB For Information Regarding This Event Please Call : (818) 622-5146 Event Date: 9/4/2016 Information Card Permit #: M4338 Agency Type: Regular Agency Name: INDEPENDENT SHAKESPEARE COMPANY, INC. Charity Event: SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL AT THE OLD ZOO , GRIFFITH PARK ZOO For Information Regarding This Event Please Call : (818) 710-6306 Event Date: 9/5/2016 Information Card Permit #: R4726 Agency Type: Regular Agency Name: WORKING CALIFORNIANS Charity Event: BENEFIT CONCERT AT EXPOSITION PARK, XMAS TREE LANE For Information Regarding This Event Please Call : (213) 452-6565 Event Date: 9/8/2016 Information Card Permit #: M4258 Agency Type: Regular Agency Name: LOS ANGELES POLICE FOUNDATION Charity Event: "LAPD ABOVE & BEYOND" AWARDS CEREMONY FUNDRAISER AT THE WESTIN BONAVENTURE HOTEL For Information Regarding This Event Please Call : (213) 489-4636 Event Date: 9/9/2016 Information Card Permit #: T3353 Agency Type: Regular Agency Name: CHINATOWN SERVICE CENTER Charity Event: 45TH ANNUAL DINNER & SILENT AUCTION FUNDRAISER AT THE WESTIN BONAVENTURE HOTEL For Information Regarding This Event Please Call : (213) 808-1700 Event Date: 9/10/2016 Information Card Permit #: M4262 Agency Type: Regular Agency Name: AMERICAN FRIENDS -

Municipal Parks, Recreation, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Public and Private Institutional Development, 1850-1980 Sub-Context: Government Infrastructure and Services, 1850-1980 Theme: Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources December 2017 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Public and Private Institutional Development/Government Infrastructure and Services/ Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 The Two Plazas, 1781-1885 6 The Pleasure Ground, 1886-1903 7 The Municipal Park, 1904-1931 11 The Early Playgrounds, 1904-1925 18 Playgrounds and Recreation, 1925-1931 22 Origins of the Recreational Facility during the Great Depression, 1932-1945 25 Early Postwar Recreational Facilities, 1945-1956 29 Late Postwar Recreational Facilities, 1957-1978 36 Postwar Golf Courses, 1945-1978 40 Hard Time during the 1970s 43 CRITERIA FOR MUNICIPAL PARKS, RECREATON, AND LEISURE 47 SUB-THEME: PLEASURE GROUNDS, 1886-1903 47 SUB-THEME: MUNICIPAL PARKS, 1904-1931 50 SUB-THEME: MUNICIPAL RECREATIONAL FACILITIES, 1932-1978 53 SUB-THEME: MUNICIPAL PARK BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES, AND FEATURES, 1886-1978 56 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 58 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Public and Private Institutional Development/Government Infrastructure and Services/ Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure, 1886-1978 PREFACE This theme of Municipal Parks, Recreation, and Leisure is a component of Los Angeles’s historic context statement, and provides guidance to field surveyors in identifying and evaluating potential historic resources relating to this category. Refer to HistoricPlacesLA.org for information on designated resources associated with this theme as well as those identified through SurveyLA and other surveys. -

Concessions and Night-Time Ticketed Events. in Recent Years, GLAZA Has Provided Significant Capital Funding for the L.A

Position Description PRESIDENT GREATER LOS ANGELES ZOO ASSOCIATION (Los Angeles, CA) THE ORGANIZATION: Mission Statement: The Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association is a nonprofit corporation created to support the Los Angeles Zoo in its mission to nurture wildlife and enrich the human experience. GLAZA’s primary responsibility is to seek and provide financial support for the Zoo’s programs and capital projects. The Los Angeles Zoo and Botanical Gardens (the “L.A. Zoo”) opened to the public in 1966 in its current location, following the closure of the original Griffith Park Zoo. Open 364 days each year (closed on Christmas Day), the L.A. Zoo is owned and operated by the City of Los Angeles. The L.A. Zoo exhibits approximately 1,100 animals on 113 acres and is dedicated to creating a unique environment for conservation, recreation and discovery. The L.A. Zoo is accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (“AZA”) and the American Association of Museums (“AAM”). The Greater Los Angeles Zoo Association (GLAZA) was created in 1963 as the support partner of the L.A. Zoo in its mission to nurture wildlife and enrich the human experience. Today, GLAZA operates and manages seven essential departments at the L.A. Zoo – fundraising, membership, publications, volunteers, special events, concessions, marketing and public relations through an Operating Agreement, a Concessions Agreement and various Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) with the City of Los Angeles and the Department of the L.A. Zoo. Over the last five decades, the L.A. Zoo has served as an important cultural venue for the community. -

National Philanthropy Day 2014

National Philanthropy Day® Not yet a member? Join AFP by November 30 and you’ll receive $50 off the cost of a new professional or associate membership. Sign up at www.afpnet.org and use the discount code NPD2014. Questions? Call the AFP Membership Department at (800) 666-3863. About the Association of Fundraising Professionals The 30,000 members of AFP are respected throughout the world for advancing ethical and eff ective fundraising. The Golden Gate Chapter, one of the largest in the U.S., works to strengthen the Bay Area social sector by providing professional development to those charged with raising the November 4, 2014 resources that move missions into action. AFP Golden Gate is deeply grateful for the generous support from foundations, corporations and individuals that make its educational programs and contributions to the fi eld possible. The Westin St. Francis Hotel Grand Ballroom AFP Golden Gate 3871 Piedmont Avenue PMB 24 335 Powell Street Oakland, CA 94611 San Francisco, California www.afpgoldengate.org Follow us on Twitter @GoldenGateAFP Tweet about NPD2014: #afpgold Like us on Facebook Event Committee Event Co-Chairs Rebecca Schuett Gwen Sobolewski CO-CHAIR CO-CHAIR California Academy of Sciences Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy Welcome Y’Anad Burrell Brandy Vause Sponsorship Dear Friends of Philanthropy, NPD MARKETING CHAIR Committee Bay Area Discovery Museum Glass House Communications Nicole C. Brown On behalf of the Association of Fundraising In Tribute Committee SPONSORSHIP CO-CHAIR Professionals Golden Gate, we welcome you to Awards Committee GLIDE Audrey Yee the 28th celebration of National Philanthropy Day. Caitlin Croughan Robin L. -

Speakeasy at DOOR 301

CATALOG COVER 5.5” x 8.5” 4-color process (4/0) OUR LADY OF MOUNT CARMEL SCHOOL Speakeasy at DOOR 301 2019 BENEFIT AUCTION AND CASINO NIGHT Strawflower Village 80 N. Cabrillo Highway Half Moon Bay WE ARE THANKFUL TO THE FOLLOWING SPONSORS OF Puttin’ On The Ritz ABC Toy Garage The Bee’s Knees The Amirkhan Family Avidbank: Fergal O’Boyle Broadway Mechanical Contractors Crippen & Flynn Funeral Chapels The Wiecks Family The Hotsy Totsy Bay Laurel Law, PC: William Francis Adasiewicz Energy House, Christian and Kristen Quint HouseDesignPlus.com Mrs. Jeri Daines, Realtor Lindblom Dental Phil and Stephanie Howard, in honor of Pierce Howard Rim Orthodontics Uccelli Agency The Blind Pig Mrs. Julie Griffith Ed Gory – Intero Real Estate Pettinelli Financial Partners The Giggly Water Giorgi Bros. Furniture Key Market Rivera Chiropractic Group Romig Engineering Schedule of Events Time Event 5:15 pm Bidder registration opens 5:30 pm Silent Auction bidding begins Cocktails and appetizers 6:30 pm 1st Grade classroom closes 6:40 pm Kindergarten classroom closes 6:50 pm TK classroom closes 7:00 pm Dinner 8:00 pm Live Auction begins Casino, dancing and music begins immediately following the Live Auction 11:00 pm Last call 11:30 pm Casino closes, winners announced 12:00 am Event concludes. Thank you for attending. Be sure to check out by Sunday at noon, and drive safely! Sunday, October 13 9:30am Bank opens Check out at the Science Center, and pick up of auction items in Kindergarten classroom 12:00pm Bank closes From the Principal Shhh….