Eric Linklater's 'Juan in America'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORKNEY BOOKS CATALOGUE SEPTEMBER 2021 Please Email Queries to Bi [email protected] Or Telephone 07496 122658

ORKNEY BOOKS CATALOGUE SEPTEMBER 2021 Please email queries to bi [email protected] Or telephone 07496 122658 Around Orkney; A Picture Guide. Lerwick: Shetland Times Ltd, 2001. 1st Edition. ISBN: 1 898852 77 4. Very good. Softcover. (339) £2.00 Illustrated Guide to Orkney. Kirkwall: John Mackay, Ca 1918. Early guide published by the proprietor of Kirkwall and Stromness hotels (and with numerous adverts for the same). Some great photographs including the 'cromlech' at Brodgar and harbours at Stromness and Kirkwall. Scarce. Good +. Softcover. (3788) £20.00 Institute of Geological Sciences. One Inch Series. Scotland Sheet 120. Southampton: Director General - Ordnance Survey, 1932. Covers eastern part of Orkney Islands including Stronsay and Shapinsay. Based on the 1910 revision. Very good +. (1624) £5.00 Institute of Geological Sciences. One inch series. Scotland Sheet 122 - Sanday. Southampton: Director General - Ordnance Survey, 1932. Drift Edition. Based on the 1910 revision. Very good. (1628) £5.00 Magnus in Orkney Looking at Nature; A Story Book with Pictures to Colour. Kirkwall: Orkney Pre-School Play Association, 1989. ISBN: 0951356917. Small mark on front cover otherwise unused. Very good +. Softcover. (4961) £0.10 New North 2. The Magazine of Aberdeen University Literary Society. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Literary Society, 1967. 1st Edition. With introduction to, and short piece of writing by, George Mackay Brown. Clean copy - some marking around the staples. Good. Softcover staple bound. (4824) £1.00 Orkney Economic Review No 17. Kirkwall: Orkney Islands Council, 1997. 1st Edition. Near fine. Softcover. (4957) £0.50 Orkney Heritage Volume 1. Kirkwall: Orkney Heritage Society, 1981. 1st Edition. -

Lot 0 This Is Our First Sale Catalogue of 2021. Due to the Current Restrictions

Bowler & Binnie Ltd - Antique & Collectors Book Sale - Starts 20 Feb 2021 Lot 0 This is our first sale catalogue of 2021. Due to the current restrictions, we felt this sale was the best type of sale to return with- welcome to our first ever ‘Rare & Collectable Book Sale’… Firstly, please note that all lots within this sale catalogue are used and have varying levels of use and age-related wear. However, we can inform that all entries have come from the same vendor, whom, was the owner of an established book shop. There are some new and remaining alterations that we are making to our sales, they are as follows: 1- There will continue to be no viewing for this sale. Each lot has a description based on the information we have. Furthermore, there are multiple images to accompany each lot (which can be zoomed in on). If there is a question you have (that cannot be answered through the description or images) please contact us via email. 2- The sale will continue to be held from home; however, we will be working with a further reduced workforce. We will be unable to answer phone calls on sale day and therefore ask that if you have a request for a condition report, that these are in by 12pm on Friday 19th and that all commission bids are placed by 7pm on this same date- anything received after these times, will not be accepted. 3- Due to our current reduced workforce and the restrictions, we are working with, we will only be able to pack and send individual books. -

Under Equality's Sun: George Mackay Brown and Socialism from the Margins of Society

MacBeath, Stuart (2018) Under Equality's Sun: George Mackay Brown and socialism from the margins of society. MPhil(R) thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/8871/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Under Equality’s Sun George Mackay Brown and Socialism from the Margins of Society Stuart MacBeath, B.A. (Hons), PGDE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Philosophy (Research) Scottish Literature School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow October 2017 1 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Abbreviations 5 Introduction 6 Chapter One 13 ‘Grief by the Shrouded Nets’ –Brown’s Orcadian, British and Universal Background Chapter Two 33 ‘The Tillers of Cold Horizons’: Brown’s Early Political Journalism Chapter Three 58 ‘Puffing Red Sails’ – The Progression of Brown’s Journalism Chapter Four 79 ‘All Things Wear Now to a Common Soiling’ – Placing Brown’s Politics Within His Short Fiction Conclusion 105 ‘Save that Day for Him’: Old Ways of Living in New Times – Further Explorations of Brown’s Politics Appendices Appendix One - ‘Why Toryism Must Fail’ 117 Appendix Two - ‘Think Before You Vote’ 118 Appendix Three – ‘July 26th in Stromness’ 119 Appendix Four - The Uncollected Early Journalism of George Mackay Brown 120 2 Bibliography 136 3 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank my supervisor, Professor Kirsteen McCue, for her guidance, support and enthusiasm throughout the construction of this project. -

Charles Edward Stuart

Études écossaises 10 | 2005 La Réputation Charles Edward Stuart Murray G. H. Pittock Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/etudesecossaises/149 DOI: 10.4000/etudesecossaises.149 ISSN: 1969-6337 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version Date of publication: 31 March 2005 Number of pages: 57-71 ISBN: 2-84310-061-5 ISSN: 1240-1439 Electronic reference Murray G. H. Pittock, “Charles Edward Stuart”, Études écossaises [Online], 10 | 2005, Online since 31 March 2005, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ etudesecossaises/149 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesecossaises.149 © Études écossaises Murray G.H. Pittock Charles Edward Stuart In April 1746, as events at Culloden drifted away from the Jacobites, Lord Elcho called on his leader Charles to charge forward and save the day. When he failed to do so, and instead left the field, Elcho termed him « an Italian coward and a scoundrel» (Scott, p. 213; Ewald, 1875, II, p. 27-33), sometimes popularized as «There you go, you cowardly Italian». Elcho’s squadron of Lifeguard cavalry were one of the Jacobite army’s few crack units: their wealthy and arrogant commander had already loaned Charles Edward 1500 guineas, a loan that was never repaid: to Charles it was a wager on success, to Elcho a commercial transaction, as Frank McLynn (1988, p. 141) has argued. In April 1746, as events at Culloden drifted away from the Jacobites, a cornet in the Horse Guards noted that the Prince wanted to charge forward and save the day. Colonel O’Sullivan ordered Colonel O’Shea of Fitzjames’s (whose name did not appear in the 1984 Muster Roll) to take Charles to safety (Livingstone, 1984). -

2019 – 2020 English Literature Third Year Option Courses

2019 – 2020 ENGLISH LITERATURE THIRD YEAR OPTION COURSES (These courses are elective and each is worth 20 credits) Before students will be allowed to take one of the non-departmentally taught Option courses (i.e. a LLC Common course or Divinity course), they must already have chosen to do at least 40-credits worth of English or Scottish Literature courses in their Third Year. For Joint Honours students this is likely to mean doing one of their two Option courses (= 20 credits) plus two Critical Practice courses (= 10 credits each). 6 June 2019 SEMESTER ONE Page Body in Literature 3 Contemporary British Drama 6 Creative Writing: Poetry * 8 Creative Writing: Prose * [for home students] 11 Creative Writing: Prose * [for Visiting Students only] 11 Discourses of Desire: Sex, Gender, & the Sonnet Sequence . 15 Edinburgh in Fiction/Fiction in Edinburgh * [for home students] 17 Edinburgh in Fiction/Fiction in Edinburgh * [for Visiting Students only] 17 Fiction and the Gothic, 1840-1940 19 Haunted Imaginations: Scotland and the Supernatural * 21 Modernism and Empire 22 Modernism and the Market 24 Novel and the Collapse of Humanism 26 Sex and God in Victorian Poetry 28 Shakespeare’s Comedies: Identity and Illusion 30 Solid Performances: Theatricality on the Early Modern Stage 32 The Cinema of Alfred Hitchcock (=LLC Common Course) 34 The Making of Modern Fantasy 36 The Subject of Poetry: Marvell to Coleridge * 39 Working Class Representations * 41 SEMESTER TWO Page American Innocence 44 American War Fiction 47 Censorship 49 Climate Change Fiction -

You Can Download This Book Here in Pdf Format

CONTENTS CONTENTS ADAM DRINAN The Men of the Rocks 294 BERNARD PERGUSSON Across the Chindwin 237 JAMES PERGUSSON Portrait of a Gentleman 3" G S FRASER The Black Cherub 82 SIR ALEXANDER GRAY A Father of SociaUsm loi Scotland 3i9 NEIL M GUNN Up from the Sea 114 The Little Red Cow 122 GEORGE CAMPBELL HAY Ardlamont 280 To a Loch Fyne Fisherman 280 The Smoky Smirr o Rain 281 MAURICE LINDSAY The Man-in-the-Mune 148 Willie Wabster 148 Bum Music 149 ERIC LINKLATER Rumbelow 132 Sealskin Trousers 261 HUGH MACDIARMID Wheesht, Wheesht 64 Blind Man's Luck 64 Somersault 5^ vi CONTENTS Sabine 65 O Wha's been Here 197 Bonnie Broukit Baim 198 COLIN MACDONALD Lord Leverhulme and the Men of Lewis 189 COMPTON MACKENZIE The North Wind 199 MORAY MCLAREN The Commercial Traveller 297 DONALD G MACRAE The Pterodactyl and Powhatan's Daughter 309 BRUCE MARSHALL A Day with Mr Migou 38 GEORGE MILLAR Stone Walls . 170 NAOMI MITCHISON Samund's Daughter 85 EDWIN MUIR In Orkney 151 In Glasgow 158 In Prague 161 The Good Town 166 WILL OGILVIE The Blades of Harden 259 ALEXANDER SCOTT The Gowk in Lear 112 GEORGE SCOTT-MONCRIEFF Lowland Portraits 282 vii CONTENTS SYDNEY GOODSIR SMITH ; ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks are due, and are hereby tendered, to the following authors and publishers for permission to use copyright poems and extracts from the volumes named hereunder : John Allan and Messrs Methuen & Co Ltd for Farmer's Boy ; George Blake and William CoUins, Sons and Co Ltd for The Ship- builders ; Jonathan Cape Ltd for three poems from Collected Poems by Lilian Bowes Lyon ; James -

'Of Course, It Didn't Work—That Kind of Scheme Never Does': Scotland, the Nordic Imaginary, and the Mid- Twentieth-Centu

‘Of course, it didn’t work—that kind of scheme never does’: Scotland, the Nordic Imaginary, and the Mid- Twentieth-Century Thriller Joe Kennedy, University of Gothenburg Abstract In the course of the last two decades, nationalist politics in Scotland have pivoted away from positing a civic identity founded on traditionally Celtic motifs—clans, tartan, the Gaelic language—in order to instead imagine an independent country closely resembling its Nordic near-neighbours in economic and cultural terms. Eulogising the Nordic welfare model, some secessionists have even suggested that a post-UK Scotland could join the Nordic Council. This article seeks to contextualise conceptualisations of Scottishness which lean on the ‘Nordic’ by examining representations of Northern Europe, and Scotland’s place within it, in two mid-twentieth-century Scottish thriller novels, John Buchan’s The Island of Sheep (1936) and Eric Linklater’s The Dark of Summer (1956). Respectively a unionist and a nationalist, Buchan and Linklater find opportunities in their work to explore both continuities and discontinuities between Scotland and the Nordic countries, and both demonstrate—with varying degrees of criticality—the extent to which a putative ‘Nordic Scottishness’ slips too easily into an exclusionary cultural logic. Drawing on geocriticism, this article will problematise efforts to re-found Scottish nationalism on the basis of a Nordicised cultural identity. Keywords: Scotland; Scottish identity; geocriticism; John Buchan; Eric Linklater; Faroe Islands In November 2013, Scotland’s devolved government, led then as now by the pro-independence Scottish National Party, published a document of almost 700 pages in length entitled Scotland’s Future in anticipation of the following year’s referendum on whether the United Kingdom’s second-largest constituent nation should vacate the Union. -

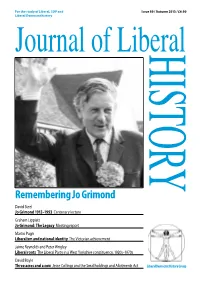

Remembering Jo Grimond

For the study of Liberal, SDP and Issue 80 / Autumn 2013 / £6.00 Liberal Democrat history Journal of LiberalHI ST O R Y Remembering Jo Grimond David Steel Jo Grimond 1913–1993 Centenary lecture Graham Lippiatt Jo Grimond: The Legacy Meeting report Martin Pugh Liberalism and national identity The Victorian achievement Jaime Reynolds and Peter Wrigley Liberal roots The Liberal Party in a West Yorkshire constituency, 1920s–1970s David Boyle Three acres and a cow Jesse Collings and the Smallholdings and Allotments Act Liberal Democrat History Group 2 Journal of Liberal History 80 Autumn 2013 Journal of Liberal History Issue 80: Autumn 2013 The Journal of Liberal History is published quarterly by the Liberal Democrat History Group. ISSN 1479-9642 Liberal history news 4 Editor: Duncan Brack Jo Grimond centenary – Orkney weekend, 18–19 May; Viscount Bryce blue Deputy Editor: Tom Kiehl plaque unveiled in Belfast; On Liberties: Victorian Liberals and their legacies; Assistant Editor: Siobhan Vitelli Liberal Democrat History Group website Biographies Editor: Robert Ingham Reviews Editor: Dr Eugenio Biagini Contributing Editors: Graham Lippiatt, Tony Little, Jo Grimond 1913 – 1993 8 York Membery David Steel’s commemoration lecture, given at Firth Kirk, Finstown, Orkney, 18 May 2013 Patrons Dr Eugenio Biagini; Professor Michael Freeden; Report 14 Professor John Vincent Jo Grimond: The Legacy, with Peter Sloman, Harry Cowie and Michael Meadowcroft; report by Graham Lippiatt Editorial Board Dr Malcolm Baines; Dr Ian Cawood; Dr Matt Cole; Dr Roy Douglas; Dr David Dutton; Prof. David Gowland; Letters to the Editor 18 Prof. Richard Grayson; Dr Michael Hart; Peter Hellyer; Honor Balfour (Mark Egan); 1963 Dumfries by-election (David Steel); Aubrey Dr Alison Holmes; Dr J. -

Beyond Words.Pub

University of Aberdeen Special Libraries and Archives Beyond Words: Illustrated Books in Aberdeen University’s Historic Collections Castle of Huldenberg in the Low Countries with its formal gardens, Plate 58 from Brabantia Illustrata (London,1702) An Information Document University of Aberdeen Development Trust King’s College Aberdeen Scotland, UK AB24 3FX T. +44(0) 1224 272097 f. +44 (0) 1224 272271 www.abdn.ac.uk/devtrust/ Engraved title page from Andreas Vesalius, De Corporis humanis Fabrica (‘Of the structure of the human body’) (Basle, 1543) [pi f611 Ves]. The plates of this anatomy textbook are celebrated as one of the finest achievements of Renaissance engraving. 2 Illustrated books constitute some of the greatest gan to exploit the possibilities of wood-engraving treasures of the Historic Library Collections in the to depict medical plants and surgical procedures. University of Aberdeen. Indeed, our holdings in Illustrations can, at such times, become the most this area are so richly representative of all styles important element on the page: this is true in and periods that only a fraction of them can be different senses for religious images, heraldry shown or described here. and scientific diagrams. The first library at King’s College (founded in 1495) held illustrated and coloured printed books, part of the progressive and reforming agenda of its founder, Bishop William Elphin- stone. Among the earliest donations to Marischal College (founded in 1593), the other constituent college of the modern University, were the illus- trated medical and scientific works given by Dun- can Liddell, the cosmopolitan humanist and sur- geon. From that time until the present day, these Collections have been continually enriched with a diversity of illustrated works originating from all over the known world, and reflecting in their Botanical illustrators at work from Leonard Fuchs, De Historia woodcut, engraved, or colour-plate illustrations Stirpium Commentarii (‘Commentaries on the History of Plants’) the wonders of that world and all that it contains. -

Orkney Library & Archive D1

Orkney Library & Archive D1: MISCELLANEOUS SMALL GIFTS AND DEPOSITS D1/1 Kirkwall Gas Works and Stromness Gas Works Plans 1894-1969 Plans of lines of gas pipes, Kirkwall, 1910-1967; Kirkwall Gas Works, layout and miscellaneous plans, 1894-1969; Stromness Gas Works plans, 1950-1953. 1.08 Linear Metres Some allied material relating to gas undertakings is in National Archives of Scotland and plans and photographs in Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. D1/2 Charter by Robert, Earl of Orkney to Magnus Cursetter 1587 & 1913 Charter by Robert, Earl of Orkney to Magnus Cursetter of lands of Wasdale and others (parish of Firth), 1587; printed transcript of the charter, 1913. The transcription was made by the Reverend Henry Paton, M.A. 0.01 Linear Metres D1/3 Papers relating to rental of lands in island of Rousay 1742-1974 Rental of lands in island of Rousay, 1742; correspondence about place of manufacture of paper used in the rental, 1973-1974. 0.01 Linear Metres English D1/4 Eday Peat Company records 1926-1965 Financial records, 1931-1965; Workmen’s time books, 1930-1931, 1938-1942; Letter book, 1926-1928; Incoming correspondence, 1929-1945; Miscellaneous papers, 1926-1943, including trading accounts (1934-1943). 0.13 Linear Metres English D1/5 Craigie family, Harroldsgarth, Shapinsay, papers 1863-1944 Rent book, 1863-1928; Correspondence about purchase and sale of Harroldsgarth, 1928-1944; Miscellaneous papers, 20th cent, including Constitution and Rules of the Shapansey Medical Asssociation. 0.03 Linear Metres English D1/6 Business papers of George Coghill, merchant, Buckquoy 1871-1902 Business letters, vouchers and memoranda of George Coghill, 1874- 1902; Day/cash book, 1871. -

SIB FOLK NEWS NEWSLETTER of the ORKNEY FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY No 80 December 2016

SIB FOLK NEWS NEWSLETTER OF THE ORKNEY FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY No 80 December 2016 P. 4 P.18 P. 7 P. 7 P.14 P. 8 P.17 P.10 P. 3 GRAPHICS JOHN SINCLAIR 2 NEWSLETTER OF THE ORKNEY FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Issue No 80 December 2016 ORKNEY FAMILY HISTORY NEWSLETTER No 80 DECEMBER 2016 COVER SIB HIGHLIGHTS PAGE 2 From the Chair PAGE 3 Anne's article brought the Orkney memories flooding back. PAGES 4, 5 & 6 From Jackie Brown faces marriage, call-up and war. the Chair PAGE 7 What's in a name? Welcome to the December issue of the Sib Folk News. I can’t believe Maybe you know? that it is that time already as we have enjoyed the best harvest weather PAGES 8 & 9 we’ve had for ages. So much started Our winter programme is already under way and I would like to thank in Upper Garth, Quholm, Stromnness Tom Muir for his very interesting talk on the local traditions around birth, marriage and death which ranged from poignant to extremely amusing. PAGES 10 & 11 The October meeting was a tribute to our ancestors who fought in William Stevenson the Somme 100 years ago and Brian Budge, our speaker, displayed Bremner Royal Navy Shipwright his encyclopedic knowledge of the battle. Brian has also gathered information of all the fallen in WW1 and has requested us to ask if any of PAGES 12 & 13 our members have photographs of their relatives who died in the war. If This will keep many you have he would be very grateful if you sent him a copy. -

Penguin Classics

PENGUIN CLASSICS A Complete Annotated Listing www.penguinclassics.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world, providing readers with a library of the best works from around the world, throughout history, and across genres and disciplines. We focus on bringing together the best of the past and the future, using cutting-edge design and production as well as embracing the digital age to create unforgettable editions of treasured literature. Penguin Classics is timeless and trend-setting. Whether you love our signature black- spine series, our Penguin Classics Deluxe Editions, or our eBooks, we bring the writer to the reader in every format available. With this catalog—which provides complete, annotated descriptions of all books currently in our Classics series, as well as those in the Pelican Shakespeare series—we celebrate our entire list and the illustrious history behind it and continue to uphold our established standards of excellence with exciting new releases. From acclaimed new translations of Herodotus and the I Ching to the existential horrors of contemporary master Thomas Ligotti, from a trove of rediscovered fairytales translated for the first time in The Turnip Princess to the ethically ambiguous military exploits of Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions, there are classics here to educate, provoke, entertain, and enlighten readers of all interests and inclinations. We hope this catalog will inspire you to pick up that book you’ve always been meaning to read, or one you may not have heard of before. To receive more information about Penguin Classics or to sign up for a newsletter, please visit our Classics Web site at www.penguinclassics.com.