Harnetty, Brian 11-24-14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

Rezension Für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Rezension für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings Ludwig van Beethoven | Claude Debussy | Maurice Ravel | Frédéric Chopin | Sergei Prokofiev | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 4CD aud 21.404 Radio Stephansdom CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 ( - 2009.09.04) Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzter Ton" und... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Neue Musikzeitung 9/2009 (Andreas Kolb - 2009.09.01) Konzertprogramm im Wandel Konzertprogramm im Wandel Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Piano News September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 (Carsten Dürer - 2009.09.01) Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 388 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 (Wilfried Bestehorn, Oliver Schwesig - 2009.09.14) In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven auf CD herausgebracht. Inzwischen sind bereits 40 CD's erschienen mit Aufnahmen von Furtwängler und Fricsay, von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau u. v. a. Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm. Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker: Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. -

Educational Materials to Go with the Video & Extra Materials For

Educational Materials to go with the Video & extra materials for preparation and extension of the concert Prepared by Valerie Trollinger ([email protected], or [email protected] ) October 2012 Discovery Concert Series The Science of Sound Reading Symphony Orchestra Discovery Concert Series October, 2012 The Thrill of Resonance (Grades 4 , and above; Grade 3 with help) Teacher Quick-Start Guide The video is the second one in our sequence about the Science of Sound. There are three (3) ways to use this series at this point: 1) For students to get the full benefit of the science behind the sounds, then viewing the first video “The Science of Sound” is strongly recommended. a. Show the first video in the sequence (The Science of Sound) with the accompanying worksheet, go over the worksheet as needed. When the students are familiar with the meaning of the words Frequency, Amplitude, Time, Dynamics, and the rest of the terms on the worksheet, then go on to the second video (The Thrill of Resonance) with that accompanying worksheet. From there you can continue with activities that are relevant to your curriculum. There are a lot of other activities that go with both of these videos, addressing STEM technology ( adding the arts ) and building on creative thinking, problem solving, critical thinking, reading, writing, and even engineering. 2) If you don’t have time for the first video at this point and want to only show the second-- a) The students still need to be familiar with the terms Frequency, Amplitude, and Time. Definitions will follow in the teacher pack. -

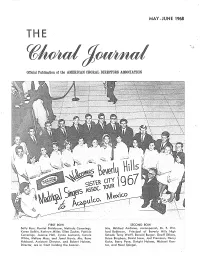

May -June 1968 T E

MAY -JUNE 1968 T E Official Publication of the AMERICAN CHORAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION FIRST ROW SECOND ROW Sally Ross, Harriet Steinbaum, Melinda Cummings, Mrs. Mildred Andrews; accompanist; Dr. F. Wil Karen Balkin, Kathryn Miller, Ellen Zucker, Patricia lard Robinson, Principal of Beverly Hills High Cummings, Joanne Hall, lynne Levinson, Carole School; Terry Wolff, Ronald Burger, Geoff Shlaes, White, Melissa Moss, and Janet Harris. Mrs. Rena Brian Bingham, David Loew; Joel Pressman, Henry Hubbard, Assistant Director, and Robert Holmes, Kahn, Barry Pyne, Dwight Holmes, Michael Kan Director, are in front holding the banner. tor, and Neal Spiegel. vent with numerical superiority and fi ic, festival, or meeting by which more d)1UUH tIt,e ------1 nancial strength to speak as the choral choral directors will become aware of voice of this country an'd still maintain the aims, purposes and value of ACDA. our 'dues at the present level of $6.00 a This issue carries the first Dues No Executive Secretary's year the need to double our membership tice for the 1968-69 fiscal year. Although this coming year was expressed by Pres July 1 is the first day of that year, many '--------:Jluk ident Decker and the National, Divisional of you win be away on vacation or at While it. fs impossible to report in de and ,State officers. A renewed plea was summer school and it is the hope of the tail on all meetings of the National issued that each ACDA member make it executive committee that you will help Board, the Executive Committee, the Di his personal obligation to bring in one both the organization and yourself by vision and state Chairmen and open new member this fall to swell the ranks paying your dues now before the end of sessions, several important plans and of ACDA to help us through this coming the current school year. -

Feature Film Project Summary Logline Synopsis

HERE Feature Film Project Summary A Braden King Film Written by Braden King and Dani Valent Producers: Lars Knudsen, Jay Van Hoy Co-Producer: Jeff Kalousdian Executive Producers: Zoe Kevork, Julia King A Truckstop Media / Parts and Labor Production 302A W. 12th St., #223 New York, New York 10014 (212) 989-7105 / [email protected] www.herefilm.info Logline HERE is a dramatic, landscape-obsessed road movie that chronicles a brief but intense romantic relationship between an American satellite-mapping engineer and an expatriate Armenian art photographer who impulsively decide to travel together into uncharted territory. Synopsis Will Shepard is an American satellite-mapping engineer contracted to create a new, more accurate survey of the country of Armenia. Within the industry, his solitary work - land-surveying satellite images to check for accuracy and resolve anomalies - is called “ground-truthing”. He’s been doing it on his own, for years, all over the world. But on this trip, his measurements are not adding up. Will meets Gadarine Najarian at a rural hotel. Tough and intriguing, she’s an expatriate Armenian art photographer on her first trip back in ages, passionately trying to figure out what kind of relationship - if any - she still has with her home country and culture. Fiercely independent, Gadarine is struggling to resolve the life she’s led abroad with the Armenian roots that run so deeply through her. There is an instant, unconscious bond between these two lone travelers; they impulsively decide to continue together. HERE tells the story of their unique journey and the dramatic personal transformations it leads each of them through. -

Varsity Jazz

Varsity Jazz Jazz at Reading University 1951 - 1984 By Trevor Bannister 1 VARSITY JAZZ Jazz at Reading University 1951 represented an important year for Reading University and for Reading’s local jazz scene. The appearance of Humphrey Lyttelton’s Band at the University Rag Ball, held at the Town Hall on 28th February, marked the first time a true product of the Revivalist jazz movement had played in the town. That it should be the Lyttelton band, Britain’s pre-eminent group of the time, led by the ex-Etonian and Grenadier Guardsman, Humphrey Lyttelton, made the event doubly important. Barely three days later, on 3rd March, the University Rag Committee presented a second event at the Town Hall. The Jazz Jamboree featured the Magnolia Jazz Band led by another trumpeter fast making a name for himself, the colourful Mick Mulligan. It would be the first of his many visits to Reading. Denny Dyson provided the vocals and the Yew Tree Jazz Band were on hand for interval support. There is no further mention of jazz activity at the university in the pages of the Reading Standard until 1956, when the clarinettist Sid Phillips led his acclaimed touring and broadcasting band on stage at the Town Hall for the Rag Ball on 25th February, supported by Len Lacy and His Sweet Band. Considering the intense animosity between the respective followers of traditional and modern jazz, which sometimes reached venomous extremes, the Rag Committee took a brave decision in 1958 to book exponents of the opposing schools. The Rag Ball at the Olympia Ballroom on 20th February, saw Ken Colyer’s Jazz Band, which followed the zealous path of its leader in keeping rigidly to the disciplines of New Orleans jazz, sharing the stage with the much cooler and sophisticated sounds of a quartet led by Tommy Whittle, a tenor saxophonist noted for his work with the Ted Heath Orchestra. -

A Lengthwise Slash David Grubbs, 2011 I First Met Arnold Dreyblatt In

A Lengthwise Slash David Grubbs, 2011 I first met Arnold Dreyblatt in 1996 when he came to Chicago at Jim O’Rourke’s urging. At the time Jim and I were the two core members of the group Gastr del Sol, and we also co-directed the Dexter’s Cigar reissue label for Drag City. The basic idea of Dexter’s Cigar was that there were any number of out-of-print, underappreciated recordings that, if heard, would put contemporary practitioners to shame. Just try to stack your solo free-improv guitar playing versus Derek Bailey’s Aida. Think your power electronics group is hot? Care to take a listen to Merzbow’s Rainbow Electronics 2? Do you fancy a shotgun marriage of critical theory and ramshackle d.i.y. pop? But you’ve never heard the Red Krayola and Art and Language’s Corrected Slogans? Gastr del Sol work time was as often as not spent sharing new discoveries and musical passions. Jim and I both flipped to Dreyblatt’s 1995 Animal Magnetism (Tzadik; which Jim nicely described “as if the Dirty Dozen Brass Band got a hold of some of Arnold’s records and decided to give it a go”) as well as his ingenious 1982 album Nodal Excitation (India Navigation), with its menagerie of adapted and homemade instruments (midget upright pianoforte, portable pipe organ, double bass strung with steel wire, and so on). We knew upon a first listen that we were obliged to reissue Nodal Excitation. The next time that Arnold blew through town, we had him headline a Dexter’s Cigar show at the rock club Lounge Ax. -

Attentional Limitations in Dual-Task Performance

CHAPTER FOUR Attentional Limitations in Dual-task Performance Harold Pashler University of California, USA James C. Johnston NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, USA INTRODUCTION People's ability (or inability) to do different activities or tasks at the same time is a topic of much interest not only to psychologists, but also to the proverbial "person in the street". It is natural to wonder about what we as human beings can and cannot do. An understanding of our limitations should also have practical value, because the intelligent design of human/machine systems depends as much on knowing the capabilities of people as it does on knowing the capabilities of machines. Human performance limits have played an important role in catastrophes that have occurred in aviation and other fields; a better understanding of those limits might help in designing systems and procedures that can minimize the frequency of such disasters. Simultaneous performance of different tasks is intellectually intriguing as well. The limitations on simultaneous cognition may provide important clues to the architecture of the human mind. The notion that dual-task performance limitations have implications about the "unity of the mind" occurred to people long before the present era of information-processing psychology. In the late nineteenth century, for example, the educated public was fascinated with a phenomenon called "automatic writing", in which People were claimed to be able to write prose while carrying out other tasks (see Koutstaal, 1992). This chapter provides an overview of research on attentional limitations dual-task performance. The organization of the chapter follows a plan 155 4. -

The Place of Music, Race and Gender in Producing Appalachian Space

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Geography Geography 2012 PERFORMING COMMUNITY: THE PLACE OF MUSIC, RACE AND GENDER IN PRODUCING APPALACHIAN SPACE Deborah J. Thompson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Thompson, Deborah J., "PERFORMING COMMUNITY: THE PLACE OF MUSIC, RACE AND GENDER IN PRODUCING APPALACHIAN SPACE" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Geography. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/geography_etds/1 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Geography by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Fusing the Voices: the Appropriation and Distillation of the Waste Land

Fusing the voices: the appropriation and distillation of The waste land Martin John Fletcher Submetido em 19 de julho de 2015. Aceito para publicação em 23 de outubro de 2015. Cadernos do IL, Porto Alegre, n.º 51, dezembro de 2015. p. 51-66 ______________________________________________________________________ POLÍTICA DE DIREITO AUTORAL Autores que publicam nesta revista concordam com os seguintes termos: (a) Os autores mantêm os direitos autorais e concedem à revista o direito de primeira publicação, com o trabalho simultaneamente licenciado sob a Creative Commons Attribution License, permitindo o compartilhamento do trabalho com reconhecimento da autoria do trabalho e publicação inicial nesta revista. (b) Os autores têm autorização para assumir contratos adicionais separadamente, para distribuição não exclusiva da versão do trabalho publicada nesta revista (ex.: publicar em repositório institucional ou como capítulo de livro), com reconhecimento de autoria e publicação inicial nesta revista. (c) Os autores têm permissão e são estimulados a publicar e distribuir seu trabalho online (ex.: em repositórios institucionais ou na sua página pessoal) a qualquer ponto antes ou durante o processo editorial, já que isso pode gerar alterações produtivas, bem como aumentar o impacto e a citação do trabalho publicado. (d) Os autores estão conscientes de que a revista não se responsabiliza pela solicitação ou pelo pagamento de direitos autorais referentes às imagens incorporadas ao artigo. A obtenção de autorização para a publicação de imagens, de autoria do próprio autor do artigo ou de terceiros, é de responsabilidade do autor. Por esta razão, para todos os artigos que contenham imagens, o autor deve ter uma autorização do uso da imagem, sem qualquer ônus financeiro para os Cadernos do IL. -

Valuing Families. Activity Guide. INSTITUTION National Board of Young Men's Christian Associations, N6w York, N.Y.; YMCA of Akron, Ohio

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 107 551 SO 008 310 AUTHOR Glashagel, Jerry; Glashagel, Char TITLE Valuing Families. Activity Guide. INSTITUTION National Board of Young Men's Christian Associations, N6w York, N.Y.; YMCA of Akron, Ohio. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (DHEW/PHS), Rockville, Md. PUB DATE [75] NOTE 42p.; For related document, see SO 008 309 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.95 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Achievement; *Activity Units; Alcohol Education; Family (Sociological Unit); Family Attitudes; Family Life; *Family Life Education; Family Problems; *Family Relationship; Group Activities; Learning Activities; Personal Values; *Resource Guides; Self Concept; Self Esteem; Self Expression; *Values IDENTIFIERS *Youth Values Project ABSTRACT Developed as a resource for family life education, this activity guide can be used to lead experiential learning situations for intergenerational groups by a counselor, in a course, in a family organization like the YMCA, or in the home. The goals of this guide are to increase the self-esteem of each person and to strengthen the family as a human support system. A short section explains values and valuing, and some ground rules are suggested for use when conducting activity units. Twenty-three activity units are provided, which cover the following topics: achievement, sharing and caring, respect, self- awareness, and aids and escapes. The objectives, process, materials, and total time needed are given for each activity. Materials are included in the booklet and can also be found in the home. An explanation is the Photo Story activity for _which photographs are supplied that cannot be reproduced, however, pictures can be clipped from magazines as a replacement.