Transformative Professional Development for Early Care and Education Program Providers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOUTHEAST REGION CUMULATIVE GIVING Gifts As of January 13, 2021

SOUTHEAST REGION CUMULATIVE GIVING Gifts as of January 13, 2021 The Museum’s Southeast Regional Office serves Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. By inscribing the names of donors in perpetuity on the Museum’s walls, we recognize the generosity of individuals, families, corporations, and foundations in the southeast region that have made cumulative gifts above $50,000. Their donations were vital to the Museum’s creation and continue to sustain the Museum’s ability to acquire artifacts, develop new exhibitions, undertake scholarly research, and provide vital programming. GIFTS OF $30 MILLION OR MORE GIFTS OF $1 MILLION OR MORE Bernard Aptaker* Madlyn and Leonard Abramson Eric F. and Lore Ross* Anonymous Ted* and Lin Arison GIFTS OF $6 MILLION OR MORE David and Betty-Jean Bavar Deanie and Jay Stein Norman and Irma Braman Dorothy and Maurice* Bucksbaum GIFTS OF $5 MILLION OR MORE Rhoda and David* Chase Anne and Isidore Falk Charitable Foundation The Coca-Cola Company Sidney and Kyra Ferenc GIFTS OF $4 MILLION OR MORE Max M.* and Marjorie S. Fisher Planethood Foundation, Inc. Estate of Carl L. Glassberg Sylvia Greenberg GIFTS OF $3 MILLION OR MORE Murray H. and Joan M. Goodman Dennis Schuman Living Trust Nathan and Sophia Gumenick* Joseph Gurwin Family Foundation GIFTS OF $2 MILLION OR MORE Konover South Development Corporation Charles S. Ackerman* Murray Koppelman Anonymous Ann Wolk Krouse and Paul C. Krouse* Howard L. and Judie Ganek Mr. and Mrs. Robert Patron, and Marcia Patron* Estate of Andrew Harper Julie Peyton Jack and Barbara Kay* Pearl Resnick* Bernie and Doris Marcus Marcus and Ann Rosenberg Foundation Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family Foundation Irving and Helen* Schneider Fern and Manfred Steinfeld Family Richard Schwartz John and Janet Swanson Mickey and Karen Shapiro Elizabeth G. -

Mapping Collier County: an Early Learning Systems Landscape Analysis

Mapping Collier County: An Early Learning Systems Landscape Analysis A REPORT FOR FUTURE READY COLLIER Lastinger Center for Learning UNIVERSITY of FLORIDA Underwritten by: Created by: University of Florida Lastinger Center for Learning and The Anita Zucker Center for Excellence in Early Childhood Studies Proudly Commissioned and Underwritten by: Founders of the Naples Winter Wine Festival Suggested Citation for this report: Rodgers, M.K. & Poekert, P. (2019). Mapping Collier County: An Early Learning Systems Landscape Analysis. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida. Contents Introduction ..........................................................................1 Building Lasting Partnerships. .4 Why a Landscape Analysis?. 4 Executive Summary ...................................................................6 Phase 1 Findings: Previous inputs and research. .7 Phase 2 Findings: Current data gathering and stakeholder input ..........................7 Phase 3 Findings: Case study analysis to determine common levers of change .............8 Background ..........................................................................9 Glossary. 11 Methodology and Limitations ...........................................................13 Data Collection ...................................................................13 Data Analysis .....................................................................14 Limitations .......................................................................15 Phase 1: Key Findings from Previous Work and Inputs (2013-2017) -

072913 Really Really Final Jsp Fall 2013 Newsletter

FALL College 2013COLLEGE of Charleston, Fall 2004of Page 1 1 CHARLESTON Yaschik/Arnold Jewish Studies Program rwdl rwdm from generation to generation FALL 2013 2 Yaschik/Arnold Jewish Studies Program The Synergy of Jewish Studies Jewish Studies has come a very long way in its relatively short history, and the rest of this newsletter highlights the everyday activities that make the program so vibrant. In this letter, I will focus on the structure of the program, its faculty and staff, that make it all happen. As I have emphasized repeatedly, Jewish Studies has a unique administrative structure since academics, student life, and community outreach are all under the same umbrella, though with different funding sources. Essentially, the academic side is funded by College of Charleston dollars, while the student and community outreach components are funded by endowment monies (housed at the College of Charleston Foundation), foundation grants, and our increasingly important annual fund. The academic side has four full-time designated faculty positions in Jewish Studies and Hebrew (Josh Shanes, David Slucki temporarily replacing Adam Mendelsohn, Oren Segal succeeding Tsipi Wagner, and me), Ted Rosengarten, the Zucker/Goldberg Professor of Holocaust Studies, and the Arnold Distinguished Visiting Professor of Jewish Studies (Gary Zola this spring). Larry Krasnoff, a professor of philosophy, is the Associate Director of Jewish Studies and Jewish Studies has faculty from other departments who teach regularly in the program. The College offers a Jewish Studies major and minor, a dozen courses each semester, and travel courses, all as part of its academic mission. By the way, the large majority of students enrolled in Jewish Studies courses are not Jewish. -

120913 Jsp Spring 2014 Newsletter

SUNDAY PROGRAMS START AT 10:00AM College of Charleston, Fall 2004 Page 1 SPRING 2015 1 Yaschik/Arnold Jewish Studies Program rwdm 2015 rwdlfrom generationSPRING to generation 2 Yaschik/Arnold Jewish Studies Program REACHING OUT Martin Perlmutter, Director, Yaschik/Arnold Jewish Studies Program Jewish Studies at the College is proud of its history of broadening the umbrella to include a wide range of constituencies. The academic component is crucial for a university setting, so extensive coursework, a first-rate faculty, a major and minor in Jewish Studies, and three years of Hebrew instruction are at the heart of what we do. The academic side includes outreach, since the majority of students enrolled in our courses are not Jewish. But we have always thought of Jewish Studies far more broadly, extending our reach to both students outside the classroom and the larger community. Our organizational and financial structures are unique in that way; they are unlike any other Jewish Studies program in the country. Our model has enabled us to provide a range of programs like Chanukah in the Square, A World of Jewish Culture at Piccolo Spoleto, Sunday Morning Brunches, Three Rabbi Panels, Brown Bag Lunches, and the Jewish Historical Society of South Carolina on the community side; and Wednesday night Meet to Eats, Shabbat services and dinners, Birthright Israel, the Carolina Youth Development Center, and regular social programming on the student side. Our kosher vegan/vegetarian dining hall, designed to service both students and the larger community, is “scheduled” to open in November 2015. That is an ambitious outreach project, one which is well under way. -

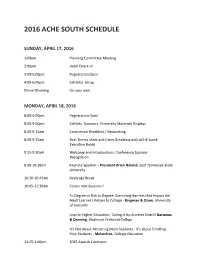

2016 Ache South Schedule

2016 ACHE SOUTH SCHEDULE SUNDAY, APRIL 17, 2016 1:00pm Planning Committee Meeting 3:00pm Hotel Check-in 3:00-5:00pm Registration Open 4:00-6:00pm Exhibitor Setup Dinner/Evening On your own MONDAY, APRIL 18, 2016 8:00-4:00pm Registration Open 8:00-5:00pm Exhibits, Sponsors, University Materials Displays 8:30-9:15am Continental Breakfast / Networking 8:30-9:15am First Timers Meet and Greet Breakfast with ACHE South Executive Board 9:15-9:30am Welcome and Introductions, Conference Sponsor Recognition 9:30-10:30am Keynote Speaker – President Brian Noland, East Tennessee State University 10:30-10:45am Beverage Break 10:45-11:30am Concurrent Sessions I To Degree or Not to Degree: Examining Barriers that Impact the Adult Learner's Return to College - Bergman & Osam, University of Louisville Lean-in Higher Education: Taking It Up Another Notch! Bartanus & Denning, Piedmont Technical College It's Not About Attracting More Students - It's about Enrolling Your Students - Melendres, Collegis Education 11:45-1:00pm 2015 Awards Luncheon 1:00-1:45pm Message from ACHE President/Conversations with Vendors/Business Meeting/Door Prize drawing 2:00-2:45pm Concurrent Sessions II All for One & One for All: Assessing the Effectiveness of Feedback Delivery in Online Writing - Singleton, Northern Kentucky University Palmetto College: A System Approach to Accessible, Affordable & Flexible Degrees - Elkins, Colbert, Nesmith, Carmichael, Catalano, Collins & Sonntag, University of South Carolina An Innovative Approach to Improving the Recruitment & Success of Transfer Students – Harrison, Rainbolt & Delozier, East Tennessee State University 3:00pm Tours/Outings/Activities in the area (History, Art, Cultural) Dinner/Evening On your own TUESDAY, APRIL 19, 2016 8:30-11:00am Registration open 8:30-3:00pm Exhibits, Sponsors, University Materials Displays 8:30-10:00 am Continental Breakfast/Keynote – Ms. -

2012–13 Annual Report (PDF)

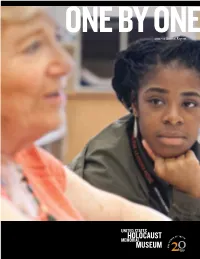

ONE BY ONE2012–13 Annual Report With the survivors at our side, Leadership Message 4 Rescuing the Evidence 8 for two decades this sacred Advancing New Knowledge 10 place has challenged leaders Educating New Generations 12 Preventing Genocide 14 and citizens, teachers and The Power of Our Partnership 16 students—one by one—to 20th Anniversary National Tribute 18 International Travel Program 22 look inside themselves, Campaign Leadership Giving 24 to look beyond themselves, Donors 26 Financial Statements 46 and to wrestle with some of United States Holocaust Memorial Council 47 the most central issues of human behavior in modern society. So to the question: Does memory have the power to change the world? 20 years on, our answer is a resounding YES. —Sara J. Bloomfield, Director 39 million 90,000 446 50,000 10% 143,000 Since 1993, 39 million people More than 80,000 national Representing diverse Over 50,000 educators—from Our website ushmm.org— Inspired by the Museum’s have had an in-person encounter and local law enforcement academic disciplines, 446 those at the beginning of their now available in 15 languages contemporary genocide with our most important message: professionals and 10,000 scholars from 30 countries careers to the most advanced— including Arabic, Chinese, Farsi, installation FROM MEMORY The Holocaust could have been members of the US court have completed resident have been trained by the Russian, Spanish, Turkish, and TO ACTION: MEETING THE prevented. Over 35 million people system have participated in fellowships at the Museum’s Museum in the most effective Urdu—has become the leading CHALLENGE OF GENOCIDE, have visited the Museum on the Museum training programs, Center for Advanced ways to teach this history. -

A PUBLICATION of BISHOP GADSDEN View the GAB Online At

September 2019 Issue 353 Gadsden GAB A PUBLICATION OF BISHOP GADSDEN View the GAB online at www.bishopgadsden.org. YEARS OF DEDICATION BY OUR STAFF: FINAL IN THE SERIES Faith Dodge In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Bill Trawick was searching for the direction his professional life would take. He had obtained an undergraduate degree in English from East Carolina University and a Masters in Literature from The American University, believing he wanted to be a college English professor. Being a consummate “people” person, he realized he was not going to do the research and publishing required to be successful at this endeavor. He INSIDE THIS had two good jobs in Washington, D.C. that were political appointments with the Carter ISSUE: Administration. He was then hired as the Legislative 2 Water Water Assistant to Congressman Richard Ottinger and worked on Everywhere Capitol Hill from 1981 to 1984. It was during this time that Bill began to develop his 3 Message from interest in health care and the demographics of the rapidly President/CEO growing senior population. He attended the University of Maryland in the evenings to obtain a Master’s degree in 3 Grasslands Health Care Administration along with a Master’s 4-5 Apollo 11-Trip to Certification in Gerontology, with the intention of the Moon continuing in the public policy field. The rector of the church where Bill was active, St John’s Episcopal Church 5 BG Eats Out on Lafayette Square, took him to an Episcopal Continuing 6 Back in Time Care Retirement Community. Bill says that visit changed the course of his professional life, as he knew at that 7 Cars, Clothes, moment what he wanted to do with his future. -

Expedition for Assets Our Movement

2015 Annual Report Expedition For Assets Our Movement Mission Board of Directors Michael Brown Metanoia Community Development Corporation Erica Fludd is a movement of people, rooted in faith. We Blake Hart Rashawnna Hawkins invest in neighborhood assets to build leaders, Belinda Holloway establish quality housing and generate economic Burnet Jacques development. We are pushing forward into new Lisa Mclean relationships with God and one another to create Penny Middleton Aisha Singletary strong communities. Ayesha Washington Suzanne Morse, Honorary Member Council of Advocates Vision Cindy Cartmell Greg Garvan Metanoia envisions a diverse community of Sam Hayes people that are inspired and empowered to Cyndy Keyes make the community better for generations to Marty Klaper come; where quality housing and livable wage Charles Larsen Carole Mauldin jobs are accessible to all; where there are aca- Connor McIntyre demically achieving schools; where businesses Matthew Pardieck and faith communities benefit the community; Wayne & Cheryl Patterson Eric Porterfield where the quality of life includes green space and Terry & Tammy Thompson recreational opportunities; and where Reynolds Avenue is a hub of economic and social activities. We recognize the people of our community are essential to the accomplishment of this vision. Metanoia Community Development Corporation 2005 Reynolds Avenue North Charleston, SC 29405 t: (843) 529-3014 f: (843) 529-3639 www.pushingforward.org /MetanoiaSC @pushing_forward /MetanoiaCDC “HERE WE DISCOVER AND GROW ASSETS” Dear Metanoia Family, Those of you who have visited us at Metanoia know that the sentence above is displayed in large letters across the wall of our main office conference room. We work in a society that constantly wants to remind us of the problems of our neighborhood, reducing the community to nothing more than a collection of needs. -

2015 Donor's Campaign to End Premature Birth

FOR APPROVAL ONLY - 7.20.16 Campaign to End Premature Birth The March of Dimes acknowledges a special group of donors who, in 2015, pledged to support the Campaign to End Premature Birth. The campaign is our high-priority, major gifts initiative powered by generous supporters who are part of the movement to unite health care providers, researchers, hospitals, insurers, public health officials, public policy experts and others to realize a future with far fewer preterm births and far more babies born healthy and full term. The March of Dimes is incredibly grateful and recognizes these new pledges and gifts initiated in 2015: Anonymous (2) Pat and Jenny Kernan Vice Admiral Regina Benjamin Margaret Leigh Kessler Mrs. Lloyd Bentsen Tom and Susan Koltun Jackie and Mike Bezos Dr. David Lakey Jeff and MacKenzie Bezos Steven and Chani Laufer Mrs. Maripeg Bruder Mark and Brandy Letson Gretchen E. Carlson Jack and Cherie Lucks Clara Jane Carter Ron and Cindy Marks Dorothy and Greg Chapman Mary and Brian McGeady The Chien Family Meredith Corporation Alfred Childs Deidra Merriwether Cisco Foundation in Honor of Randy Pond G. Brent and Eloise Minor Harvey Cohen, MD, PhD Jeff and Kelley Minor Kelly and Andrew Dahle Mitchell International, Inc. Sheri and Gary Dixon Dr. Carole Ober and Keith Spielfogel The Edwards Family Karen and Matthew Owens Brett Esrock D. Jay and Elizabeth Marie Pederson Francesca Finnerty Dana Points and Mark Satloff Fourjay Foundation Kathleen Roosevelt Drs. Steven and Patricia Gabbe Sue and Will Schick Christine Gattenio and Stephen Meadows Mark Selcow Aleem and Cindy Gillani Will Smith Dr. -

Executive Chef, the Sanctuary Executive Chef Brendon Bashford Is Excited by the Opportunity to Lead the Culinary Team at the Sanctuary at Kiawah Island Golf Resort

Gourmet & Grapes Sponsors Event Sponsors Signature Sponsors Mr. and Mrs. Samuel and Hyden and Associates Regina Shapiro Table Sponsors Media/Advertisement Sponsors Food and Wine Sponsors Thank You to Our Patrons Mr. and Mrs. J. Preston Covington, III Ms. Jeanelle McCain Mr. and Mrs. Edward Stiefel Mr. and Mrs. Manning Frankstone Mr. and Mrs. David L. Morrow Mr. Pete Strom and The Honorable Donna Strom Mr. and Mrs. Gary Lackey Mr. and Mrs. Gregg Morton Dr. and Mrs. Robert K. Stuart Mr. and Mrs. Steve Lunceford Mr. and Mrs. Andy Phelps Mr. and Mrs. Donald Tomlin Ms. Sheay Noel The 2014 Gourmet & Grapes Board of Directors Welcome to the Sixth Annual Gourmet & Grapes weekend at The Sanctuary at Kiawah Island Golf Resort to benefit MUSC Hollings Cancer Center. We thank you for participating in our special events and hope that you enjoy a weekend full of culinary talents. We are proud to focus the proceeds of this event towards Hollings Cancer Center’s cancer research. Our celebratory weekend features fine cuisine of the region paired with an assortment of fine wines from some of the most respected winemakers in the world. Bill Lacey Jonathan Banta Hal Jones Chairman Gourmet Committee Grapes Committee Nicole Leaf Kiki Cooper Jack Case Angie Cimino Event Coordinator Auction and Charity Committee Marketing Committee Event Committee Page 1 Special Thank You Mr. Bill Lacey for your leadership and guidance. Ms. Vicky Agnew and Mr. Mike Vegis for helping to ensure the success of another year through their public relations effort. Mr. Tom Bewley for his continued marketing overview of this event. -

Alison D Masters, Et Al. V. Gas Natural Inc., Et Al. 16-CV-02880-Verified

Case: 1:16-cv-02880-PAG Doc #: 1-1 Filed: 11/28/16 1 of 71. PageID #: 8 EXHIBIT A Case: 1:16-cv-02880-PAG Doc #: 1-1 Filed: 11/28/16 2 of 71. PageID #: 9 NAILAH K. BYRD CUYAHOGA COUNTY CUERK OF COURTS 1200 Ontario Street Cleveland, Ohio 44113 Court of Common Pleas New Case Electronically Filed: November 3, 2016 16:17 By: SETH J. LINNICK 0083494 Confirmation Nbr. 900876 ALISON D. iSUNNYi MASTERS CV 16 871400 vs. Judge: MICHAEL B. BENDER ET. AL., ET AL JOSE' A. VILLANUEVA Pages Filed: 31 Electronically Filed 11/03/2016 16:17/ / CV 16 871400 / Confirmation Nbr. 900876/CLAHJ Case: 1:16-cv-02880-PAG Doc #: 1-1 Filed: 11/28/16 3 of 71. PageID #: 10 IN THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS CUYAHOGA COUNTY, OHIO ALISON D. “SUNNY” MASTERS, on behalf ) of herself and all other similarly situated ) CASE NO.: shareholders of GAS NATURAL, ) 608 Birchwood Drive ) Willoughby, OH 44094 ) JUDGE: ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) MICHAEL B. BENDER, JAMES P. ) CARNEY, RICHARD K. GREAVES, ) VERIFIED DERIVATIVE AND ROBERT B. JOHNSTON, GREGORY J. ) CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT OSBORNE, MICHAEL R. WINTER, KEVIN ) J. DEGENSTEIN, JENNIFER HABERMAN, ) JAMES E. SPRAGUE, ) (Jury Demand Endorsed Hereon) c/o Gas Natural, Inc. ) 1375 East Ninth Street ) Suite 3100 ) Cleveland, OH 44114 ) ) JED D. HENTHORNE, ) c/o Energy West Montana, Inc. ) 1 1st Avenue South ) Great Falls, MT 59401 ) ) VINCENT A. PARISI, ) c/o Nisource Inc. ) 801 East 86th Avenue ) Merrillville, IN 46410 ) ) FR BISON HOLDINGS, INC., ) c/o Corporation Service Company ) Statutory Agent ) 2711 Centerville Rd., Suite 400 ) Wilmington, DE 19808 ) ) FR BISON MERGER SUB, INC., ) c/o CSC-Lawyers Incorporating Service ) Statutory Agent ) 50 West Broad Street, Suite 1800 ) Columbus, OH 43215 ) ) FIRST RESERVE ENERGY ) INFRASTRUCTURE FUND II,L.P., ) One Lafayette Place ) Greenwich, CT 06830 ) ) ANITA G. -

Hospital Authority Board of Trustees and University Board of Trustees

AGENDA (REGULAR AND CONSENT) HOSPITAL AUTHORITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES AND UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES May 15, 2020 MEDICAL UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL AUTHORITY (MUHA) REGULAR AGENDA Board of Trustees Meeting May 15, 2020 101 Colcock Hall/Via Teleconference Members of the Board of Trustees Mr. Charles W. Schulze, Chairman Dr. Richard M. Christian, Jr. Dr. James Lemon, Vice-Chairman Dr. Paul T. Davis Ms. Terri R. Barnes Dr. Donald R. Johnson II The Honorable James A. Battle, Jr. Ms. Barbara Johnson-Williams Mr. William H. Bingham, Sr. Dr. G. Murrell Smith, Sr. Dr. W. Melvin Brown III Mr. Michael E. Stavrinakis Dr. Henry F. Butehorn III Thomas L. Stephenson, Esq. Dr. C. Guy Castles III Dr. Bartlett J. Witherspoon, Jr. Trustees Emeriti Mrs. Margaret M. Addison Dr. Charles B. Thomas, Jr. Dr. Thomas C. Rowland, Jr. Dr. James E. Wiseman, Jr. Mr. Allan E. Stalvey Item 1. Call to Order ........................................................................................................................ Charles Schulze Chairman Item 2. Roll Call ........................................................................................................................................ Jane Scutt Assistant Board Secretary Item 3. Date of Next Meeting – June 26, 2020 (Columbia, South Carolina) ............................................ Jane Scutt Assistant Board Secretary Item 4. Approval of Minutes ............................................................................................................ Charles Schulze Chairman Approval of the minutes of