Download 2008004015OK.Pdfadobe PDF (180.62

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Secular Australia? Ideas, Politics and the Search for Moral Order in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Australia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Online University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2014 A Secular Australia? Ideas, politics and the search for moral order in nineteenth and early twentieth century Australia Gregory Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Melleuish, Gregory, "A Secular Australia? Ideas, politics and the search for moral order in nineteenth and early twentieth century Australia" (2014). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 1655. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1655 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A Secular Australia? Ideas, politics and the search for moral order in nineteenth and early twentieth century Australia Abstract This article argues that the relationship between the religious and the secular in Australia is complex and that there has been no simple transition from a religious society to a secular one. It argues that the emergence of apparently secular moral orders in the second half of the nineteenth century involved what Steven D. Smith has termed the 'smuggling in' of ideas and beliefs which are religious in nature. This can be seen clearly in the economic debates of the second half of the nineteenth century in Australia in which a Free Trade based on an optimistic natural theology battled with a faith in Protection which had powerful roots in a secular form of Calvinism espoused by David Syme. -

Randolph Hughes and Alan Chisholm: Romanticism, Classicism and Fascism

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 2001 Randolph Hughes and Alan Chisholm: Romanticism, classicism and fascism Gregory Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Melleuish, Gregory, "Randolph Hughes and Alan Chisholm: Romanticism, classicism and fascism" (2001). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 1489. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1489 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Randolph Hughes and Alan Chisholm: Romanticism, classicism and fascism Abstract During the 1930s Alan Chisholm and Randolph Hughes were located at the antipodes from each other, even as they shared many of the same aesthetic and political preoccupations. Hughes was an academic at King's College, London until he resigned his post and sought a living from his writings; Chisholm taught French at the University of Melbourne, rising eventually to the rank of professor. Separated by thousands of miles, they corresponded regularly, exchanging letters covering aesthetic, literary and political topics, as they bemoaned the state of the world around them. Outlooks were shared at a variety of levels. Both were dissatisfied: Chisholm wanted nothing more than to escape what he saw as the provincial world of Australia, and to obtain a scholarly position in England; Hughes meanwhile viewed the AngloSaxon academy of which he was a part with a jaundiced eye. -

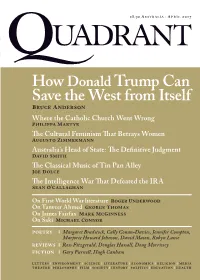

How Donald Trump Can Save the West from Itself

27/09/2016 10:23 AM 10:23 27/09/2016 (03) 9320 9065 9320 (03) $44.95 (03) 8317 8147 8147 8317 (03) fAX Quadrant, 2/5 Rosebery Place, Balmain NSW 2041, Australia 2041, NSW Balmain Place, Rosebery 2/5 Quadrant, phone quadrant.org.au/shop/ poST political fabrications. political online Constitution denied them full citizenship are are citizenship full them denied Constitution for you, or AS A gifT A AS or you, for including the right to vote. Claims that the the that Claims vote. to right the including 33011_QBooks_Ads_V5.indd 1 33011_QBooks_Ads_V5.indd had the same political rights as other Australians, Australians, other as rights political same the had The great majority of Aboriginal people have always always have people Aboriginal of majority great The Australia the most democratic country in the world. world. the in country democratic most the Australia At Federation in 1901, our Constitution made made Constitution our 1901, in Federation At peoples from the Australian nation. This is a myth. myth. a is This nation. Australian the from peoples drafted to exclude Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Islander Strait Torres and Aboriginal exclude to drafted Australian people by claiming our Constitution was was Constitution our claiming by people Australian nation complete; it will divide us permanently. permanently. us divide will it complete; nation University-based lawyers are misleading the the misleading are lawyers University-based its ‘launching pad’. Recognition will not make our our make not will Recognition pad’. ‘launching its on The conSTiTuTion conSTiTuTion The on Constitutional recognition, if passed, would be be would passed, if recognition, Constitutional The AcAdemic ASSAulT ASSAulT AcAdemic The of the whole Australian continent. -

William Forster and the Critique of Democracy in Colonial New South Wales

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 2005 William Forster and the critique of democracy in colonial New South Wales Gregory C. Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Melleuish, Gregory C., William Forster and the critique of democracy in colonial New South Wales 2005. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/177 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] William Forster and the critique of democracy in colonial New South Wales. Gregory Melleuish University of Wollongong The introduction of what have termed 'democratic' regimes into mid nineteenth century Australia in the form of the granting of responsible government to the Australian colonies has been treated in recent times as an unproblematic process. The quasi-official version of political development in the colonies, as found in the Discovering Democracy civics education programme sponsored by the Commonwealth government and expressed in the textbook written for the programme by Dr John Hirst, is that this was the first stage on the road to 'real' democracy in Australia, the final stage of which will be the establishment of an Australian republic. As Hirst sees it, the people and their politicians embraced it as an advance on the road to freedom. 1 This is Whig history in full bloom. -

IPA REVIEW ESTABLISHED in 1947 by CHARLES KEMP, FOUNDING DIRBUFOR of the INSTITUTE of PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol

IPA REVIEW ESTABLISHED IN 1947 BY CHARLES KEMP, FOUNDING DIRBUFOR OF THE INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol. 46 No. 2, 1993 Australian Disputes, Foreign Judgments 10 The Liberal Conservative Alliance in Australia 55 Rod Kemp Gregory Melleuish Foreign tribunals are usurping the role of Parliament. The evolution of a successful relationship. Debt and Sovereignty 12 In Contempt of America 58 John Hyde Derek Parker Poor economic management threatens to Americas enemy within. compromise Australias independence. Thought for Food 60 David E. Tribe Are Superannuation Funds Really Safe? 14 Useful guides through the maze created by the Nick Renton genetic revolution. There are no prescribed qualifications for trustees of superannuation schemes. Obituary 62 17 C.D. Kemp (1911-1993) Mabo and Reconciliation Ron Brunton Paul Keatings dangerous gamble. 1 Letters 3 Failing to See the Forest for the Trees 22 Bob Day IPA Indicators 4 Adopting the West African Model. Since 1989-90 Commonwealth Government spending has increased by 16.5 per cent in real terms. The Sexual harassment Inquisition 23 Andrew McIntyre From the Editor 8 The subject of an inquiry tells his disturbing story. Can the liberal-conservative marriage hold? Press Index: Mabo 16 Enforced Equality 27 How the nations editorials have judged Mabo. Stuart Wood It is wrong to infer unfair treatment simply on the Debate 20 basis of unequal outcomes. Should surrogate motherhood be legal? How to Achieve Full Employment 29 Strange Times 32 John Stone Ken Baker If the political will can be found, the solution to high Delusions of grandeur from the advocates of world unemployment is within our grasp. -

Religious Dynamics in Australian Federal Politics

Department of the Parliamentary Library Informati nand Research Services For God and Countryo' Religious Dynamics in Australian Federal Politics Dr Marion Maddox 1999Australian Parliamentary Fellow Department of the Parliamentary Library For God and Country Religious Dynamics in Australian Federal Politics Dr Marion Maddox 1999 Australian Parliamentary Fellow ISBN 0-642-52724-5 © Commonwealth of Australia 2001 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. For God and Country: Religious Dynamics in Australian Federal Politics The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and may not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS) or to the Department of the Parliamentary Library. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. Presiding Officers' Foreword Established in 1971, the Australian Parliamentary Fellowship has provided an opportunity for an academic analysis of many aspects of Parliament and the work of Parliamentarians. The work of Dr Marion Maddox, the 1999 Fellow, has been the first to assess and set in context the religious influences felt by current and past Senators and Members as they pursue their parliamentary duties. With two doctorates (in theology and political philosophy) Dr Maddox brought both fields together in her Fellowship project. In for For God and Country: Religious Dynamics in Australian Federal Politics Dr Maddox explores religious influences and debate in and around the Thirty-Eighth and Thirty-Ninth Parliaments. -

AUSTRALIA FELIX Jeremy Bentham and Australian Colonial Democracy

AUSTRALIA FELIX Jeremy Bentham and Australian colonial democracy David Geoffrey Matthew Llewellyn A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Melbourne July 2016 School of Historical and Philosophical Studies School of Social and Political Sciences Produced on archival quality paper. Abstract Jeremy Bentham considered that society should be ordered on the idea of the greatest happiness. From this foundation, he devised a democratic political system. Drawing on others’ ideas, this included: the secret ballot; payment of members of parliament; equal electoral districts; one person one vote; universal adult male and female franchise; and annual elections. It also included: a single parliamentary chamber; law made by legislation, including codification of the common law; a strong but highly accountable executive; peaceful change; and eventual colonial independence. Bentham inspired several generations of radical reformers. Many of these reformers took an interest in the colonies as fields for political experiment and as cradles for democracy. Several played a direct role in implementing democratic reform in the colonies. They occupied influential positions in Australia and in London. They sought peaceful change, and looked towards the eventual independence of the colonies. This thesis traces the influence of Bentham, and those who followed his ideas, on democratic reform in the Australian colonies. It also examines the Benthamite input into the 1838 Charter in Britain, and relationships between the Charter and subsequent reform in Australia. The thesis notes ideas implemented in Australia that emerged from the experiences of other colonies, especially Canada. The Wakefield land and emigration system, and responsible government for the colonies, both saw their genesis in the Canadian experience, and both were theorised or taken up as causes by people who were members of the Benthamite circle. -

Broad Church' Is No Longer Working Gregory C

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2018 Fractured Liberals need a new brand - 'broad church' is no longer working Gregory C. Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Melleuish, G. (2018). Fractured Liberals need a new brand - 'broad church' is no longer working. The onC versation, 15 August 1-3. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Fractured Liberals need a new brand - 'broad church' is no longer working Abstract Political parties wishing to win majority support in the pursuit of gaining control of government cannot afford to be tied too closely to a rigid ideology or set of views. They usm t accommodate a range of viewpoints and approaches to matters of public policy, even as they decide which policy to pursue. Keywords 'broad, working, -, longer, brand, need, liberals, fractured, no, church' Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Melleuish, G. (2018). Fractured Liberals need a new brand - 'broad church' is no longer working. The Conversation, 15 August 1-3. This journal article is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/3575 8/15/2018 Fractured Liberals need a new brand – 'broad church' is no longer working Academic rigour, journalistic flair Fractured Liberals need a new brand – ‘broad church’ is no longer working August 15, 2018 6.27am AEST While Labor has strengthened its message and become more united in recent years, the Liberals seem more divided than ever. -

E G Whitlam: Reclaiming the Initiative in Australian History Gregory C

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2017 E G Whitlam: Reclaiming the initiative in Australian History Gregory C. Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Melleuish, G. (2017). E G Whitlam: Reclaiming the initiative in Australian History. In J. Hocking (Ed.), Making Modern Australia: The Whitlam Government's 21st Century Agenda (pp. 308-335). Clayton, Australia: Monash University Publishing. http://www.publishing.monash.edu.au/books/mma-9781925495188.html Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] E G Whitlam: Reclaiming the initiative in Australian History Abstract How are we to understand the place of the Whitlam government in Australian history? My starting point is an observation that history is not only contingent but our understanding of it is nominalist. That is to say that it does not have a necessary, or natural, structure. We make, and re-make, narratives according to the way in which we arrange and re-arrange what we know about what has happened in the past. Human beings crave a satisfactory narrative to explain the past as a means of understanding the present but, in so doing, they usually have to make use of the imagination which can be a misleading, indeed, treacherous, friend. Keywords g, whitlam:, reclaiming, initiative, australian, history, e Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Melleuish, G. (2017). E G Whitlam: Reclaiming the initiative in Australian History. -

To Restore Federalism, Strengthen the States and Make Australia More Republican

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2014 To restore federalism, strengthen the states and make Australia more republican Gregory Melleuish University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Melleuish, Gregory, "To restore federalism, strengthen the states and make Australia more republican" (2014). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 1683. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1683 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] To restore federalism, strengthen the states and make Australia more republican Abstract The reform of Australia’s federation is under review. In this special series, we ask leading Australian academics to begin a debate on renewing federalism, from tax reform to the broader issues of democracy. The University of Wollongong’s Gregory Melleuish explains how the current state-federal relationship has warped from the ideals of Australia’s constitution and why a return to republican principles must be the remedy.>p> Keywords republican, federalism, restore, states, australia, make, strengthen, more Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Melleuish, G. (2014). To restore federalism, strengthen the states and make Australia more republican. The Conversation, (18 September), 1-5. This journal article is available at Research Online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/1683 18 September 2014, 6.29am AEST To restore federalism, strengthen the states and make Australia more republican Author 1. -

John Fairfax and the Sydney Morning Herald, 1841-1877

The Shaping of Colonial Liberalism: John Fairfax and the Sydney Morning Herald, 1841-1877. A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of New South Wales 2006 Stuart Buchanan Johnson ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ……………………………………………........................... COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. I also authorise University Microfilms to use the 350 word abstract of my thesis in Dissertation Abstract International (this is applicable to doctoral theses only).