CDA District EA Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant List As of 3/19/2008 Tanya Harvey T23S.R2E.S25, 36 *Non-Native

compiled by Bearbones Mountain Plant List as of 3/19/2008 Tanya Harvey T23S.R2E.S25, 36 *Non-native FERNS & ALLIES Taxaceae Quercus garryana Oregon white oak Dennstaediaceae Taxus brevifolia Pacific yew Pteridium aquilinum Garryaceae bracken fern TREES & SHRUBS: DICOTS Garrya fremontii Fremont’s silk tassel Dryopteridaceae Aceraceae Cystopteris fragilis Acer circinatum Grossulariaceae fragile fern vine maple Ribes roezlii var. cruentum shiny-leaved gooseberry, Sierra Polystichum imbricans Acer glabrum var. douglasii imbricate sword fern Douglas maple Ribes sanguineum red-flowering currant Polystichum munitum Acer macrophyllum sword fern big-leaf maple Hydrangeaceae Polypodiaceae Berberidaceae Philadelphus lewisii western mock orange Polypodium hesperium Berberis aquifolium western polypody shining Oregon grape Rhamnaceae Pteridiaceae Berberis nervosa Ceanothus prostratus Mahala mat Aspidotis densa Cascade Oregon grape indians’ dream Betulaceae Ceanothus velutinus snowbrush Cheilanthes gracillima Corylus cornuta var. californica lace fern hazelnut or filbert Rhamnus purshiana cascara Cryptogramma acrostichoides Caprifoliaceae parsley fern Lonicera ciliosa Rosaceae Pellaea brachyptera orange honeysuckle Amelanchier alnifolia western serviceberry Sierra cliffbrake Sambucus mexicana Selaginellaceae blue elderberry Holodiscus discolor oceanspray Selaginella scopulorum Symphoricarpos mollis Rocky Mountain selaginella creeping snowberry Oemleria cerasiformis indian plum Selaginella wallacei Celastraceae Prunus emarginata Wallace’s selaginella -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise. -

Idaho's Special Status Vascular and Nonvascular Plants Conservation Rankings

Idaho's Special Status Vascular and Nonvascular Plants Conservation Rankings 1 IDNHP Tracked Species Conservation Rankings Date USFS_ USFS_ USFS_ 2 Scientific Name Synonyms Common Name G-Rank S-Rank USFWS BLM Ranked R1 R4 R6 Abronia elliptica dwarf sand-verbena G5 S1 Feb-14 Abronia mellifera white sand-verbena G4 S1S2 Feb-16 Acorus americanus Acorus calamus var. americanus sweetflag G5 S2 Feb-16 Agastache cusickii Agastache cusickii var. parva Cusick's giant-hyssop G3G4 S2 Feb-14 Agoseris aurantiaca var. aurantiaca, Agoseris lackschewitzii pink agoseris G4 S1S2 4 S Feb-16 A. aurantiaca var. carnea Agrimonia striata roadside agrimonia G5 S1 Feb-16 Aliciella triodon Gilia triodon; G. leptomeria (in part) Coyote gilia G5 S1 Feb-20 Allenrolfea occidentalis Halostachys occidentalis iodinebush G4 S1 Feb-16 Allium aaseae Aase's Onion G2G3+ S2S3 2 Oct-11 Allium anceps Kellogg's Onion G4 S2S3 4 Feb-20 Allium columbianum Allium douglasii var. columbianum Columbia onion G3 S3 Feb-16 Allium madidum swamp onion G3 S3 S Allium tolmiei var. persimile Sevendevils Onion G4G5T3+ S3 4 S Allium validum tall swamp onion G4 S3 Allotropa virgata sugarstick G4 S3 S Amphidium californicum California amphidium moss G4 S1 Feb-16 Anacolia menziesii var. baueri Bauer's anacolia moss G4 TNR S2 Feb-20 Andreaea heinemannii Heinemann's andreaea moss G3G5 S1 Feb-14 Andromeda polifolia bog rosemary G5 S1 S Andromeda polifolia var. polifolia bog rosemary G5T5 S1 Feb-20 Anemone cylindrica long-fruit anemone G5 S1 Feb-20 Angelica kingii Great Basin angelica G4 S1 3 Mar-18 Antennaria arcuata meadow pussytoes G2 S1 Mar-18 Argemone munita ssp. -

Evolutionary Shifts Associated with Substrate Endemism in the Western American Flora

Evolutionary Shifts Associated with Substrate Endemism in the Western American Flora By Adam Christopher Schneider A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Bruce Baldwin, Chair Professor Brent Mishler Professor Kip Will Summer 2017 Evolutionary Shifts Associated with Substrate Endemism in the Western American Flora Copyright © 2017 by Adam Christopher Schneider Abstract Evolutionary Shifts Associated with Substrate Endemism in the Western American Flora by Adam Christopher Schneider Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Bruce G. Baldwin, Chair This study investigated how habitat specialization affects the evolution and ecology of flowering plants. Specifically, a phylogenetic framework was used to investigate how trait evolution, lineage diversification, and biogeography of the western American flora are affected by two forms of substrate endemism: (1) edaphic specialization onto serpentine soils, and (2) host specialization of non-photosynthetic, holoparasitic Orobanchaceae. Previous studies have noted a correlation between presence on serpentine soils and a suite of morphological and physiological traits, one of which is the tendency of several serpentine-tolerant ecotypes to flower earlier than nearby closely related populations not growing on serpentine. A phylogenetically uncorrected ANOVA supports this hypothesis, developed predominantly through previously published comparisons of conspecific or closely related ecotypes. However, comparisons among three models of trait evolution, as well as phylogenetic independent contrasts across 24 independent clades of plants that include serpentine tolerant species in California and with reasonably resolved phylogenies, revealed no significant affect of flowering time in each of these genera. -

Speciation, Species Concepts, and Biogeography Illustrated by a Buckwheat Complex (Eriogonum Corymbosum)

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2009 Speciation, Species Concepts, and Biogeography Illustrated by a Buckwheat Complex (Eriogonum corymbosum) Mark W. Ellis Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Ellis, Mark W., "Speciation, Species Concepts, and Biogeography Illustrated by a Buckwheat Complex (Eriogonum corymbosum)" (2009). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 370. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/370 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i SPECIATION, SPECIES CONCEPTS, AND BIOGEOGRAPHY ILLUSTRATED BY A BUCKWHEAT COMPLEX (ERIOGONUM CORYMBOSUM) by Mark W. Ellis A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Biology Approved: ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Paul G. Wolf Dr. Karen E. Mock Major Professor Committee Member ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Michael E. Pfrender Dr. Leila Shultz Committee Member Committee Member ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Carol D. von Dohlen Dr. Byron R. Burnham Committee Member Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2009 ii Copyright © Mark W. Ellis, 2009 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Speciation, Species Concepts, and Biogeography Illustrated by a Buckwheat Complex (Eriogonum corymbosum) by Mark W. Ellis, Doctor of Philosophy Utah State University, 2009 Major Professor: Dr. Paul G. Wolf Department: Biology The focus of this research project is the complex of infraspecific taxa that make up the crisp-leaf buckwheat species Eriogonum corymbosum (Polygonaceae), which is distributed widely across southwestern North America. -

Columbia Hills

COLUMBIA HILLS PARTIAL FLORISTIC CHECKLIST Klickitat County, WA T Compiled by David Wilderman, Lynn Cornelius, Reid Schuller, Carolyn Wright, Paul Slichter Updated by Paul Slichter on April 15, 2014. Flora Northwest- http://science.halleyhosting.com List encompasses plants seen between SR-14 and the Lyle-Centerville Highway from the Klickitat River east to US 97. Common Name Scientific Name Family Douglas' Maple Acer glabrum v. douglasii Aceraceae Big-leaf Maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae American Water Plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae Bur Chervil Anthriscus scandincina Apiaceae Hedge-parsley Caucaulis microcarpa Apiaceae Canby's Desert Parsley Lomatium canbyi Apiaceae Geyer's Desert Parsley Lomatium cf. geyeri Apiaceae Columbia Desert Parsley Lomatium columbianum Apiaceae Fern-leaved Desert Parsley Lomatium dissectum v. multifidum Apiaceae Gorman's Desert Parsley Lomatium gormanii Apiaceae Pungent Desert Parsley Lomatium grayii Apiaceae Slender-fruited Desert Parsley Lomatium leptocarpum Apiaceae Biscuitroot Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae Bare-stem Desert Parsley Lomatium nudicaule Apiaceae Salt-and-pepper Lomatium piperi Apiaceae Nine-leaf Desert Parsley Lomatium triternatum Apiaceae Watson’s Desert Parsley Lomatium watsonii Apiaceae Common Sweet-cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae Blunt-fruit Sweet-cicely Osmorhiza depauperata Apiaceae Gairdner's Yampah Perideridia gairdneri v. borealis Apiaceae Spreading Dogbane Apocynum androsaemifolium Apocynaceae Mexican Milkweed Asclepias fascicularis Asclepiadaceae Yarrow Achillea -

Vascular Plants Species Checklist

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Crater Lake National Park (CRLA) Species Checklist This species list is a work in progress. It represents information currently in the NPSpecies data system and records are continually being added or updated by National Park Service staff. To report an error or make a suggestion, go to https://irma.nps.gov/npspecies/suggest. Scientific Name Common Name Vascular Plants Alismatales/Araceae [ ] Lemna minor duckweed [ ] * Lysichiton americanus skunk cabbage Alismatales/Potamogetonaceae [ ] Potamogeton pusillus var. tenuissimus Berchtold's pondweed Alismatales/Tofieldiaceae [ ] Tofieldia glutinosa Tofieldia [ ] * Tofieldia occidentalis Apiales/Apiaceae [ ] Angelica genuflexa bentleaf or kneeling angelica [ ] Heracleum lanatum Cow Parsnip [ ] Ligusticum grayi Gray's Licoriceroot, Gray's lovage, Lovage [ ] Lomatium martindalei coast range lomatium, few-fruited lomatium, Martindale's lomatium [ ] Lomatium nudicaule barestem lomatium, pestle parsnip [ ] Lomatium triternatum nineleaf biscuitroot [ ] Osmorhiza berteroi Mountain Sweet Cicely [ ] Osmorhiza depauperata blunt- fruited sweet cicely [ ] Osmorhiza purpurea purple sweet cicely, Sweet Cicely [ ] Oxypolis occidentalis Western Oxypolis, western sweet cicely [ ] Sanicula graveolens northern sanicle, Sierra sanicle [ ] Sphenosciadium capitellatum Swamp Whiteheads, swamp white-heads, woolly-head parsnip Apiales/Araliaceae [ ] Oplopanax horridus Devil's Club Asparagales/Amaryllidaceae [ ] Allium amplectens slim-leaf onion [ ] * Allium geyeri -

Idaho's Special Status Vascular and Nonvascular Plants

Idaho's Special Status Vascular and Nonvascular Plants IDNHP Tracked Species Conservation Rankings ³ INPS 4 Scientific Name1 Synonyms Common Name² G-Rank S-Rank USFWS BLM USFS_R1 USFS_R4 USFS_R6 RPC Abronia elliptica dwarf sand-verbena G5 S1 Feb-14 Abronia mellifera white sand-verbena G4 S1S2 Feb-16 Acorus americanus Acorus calamus var. americanus sweetflag G5 S2 Feb-16 Agastache cusickii Agastache cusickii var. parva Cusick's giant-hyssop G3G4 S2 Feb-14 Agoseris aurantiaca var. aurantiaca, Agoseris lackschewitzii pink agoseris G4 S1S2 4 S Feb-16 A. aurantiaca var. carnea Agrimonia striata roadside agrimonia G5 S1 Feb-16 Allenrolfea occidentalis Halostachys occidentalis iodinebush G4 S1 Feb-16 Allium aaseae Aase's Onion G2G3+ S2S3 2 Oct-11 Allium anceps Kellogg's Onion G4 S2 4 Allium columbianum Allium douglasii var. columbianum Columbia onion G3 S3 Feb-16 Allium madidum swamp onion G3 S3 S Allium tolmiei var. persimile Sevendevils Onion G4G5T3+ S3 4 S Allium validum tall swamp onion G4 S3 Allotropa virgata sugarstick G4 S3 S Amphidium californicum California amphidium moss G4 S1 Feb-16 Andreaea heinemannii Heinemann's andreaea moss G3G5 S1 Feb-14 Andromeda polifolia bog rosemary G5 S1 S Anemone cylindrica long-fruit anemone G5 S1 Angelica kingii Great Basin angelica G4 S1 3 Mar-18 Antennaria arcuata meadow pussytoes G2 S1 Mar-18 Arabis sparsiflora var. atrorubens Boechera atroruben sickle-pod rockcress G5T3 S3 Argemone munita ssp. rotundata prickly-poppy G4T4 SH Feb-16 Artemisia borealis, A. campestris ssp. borealis, Artemisia campestris ssp. borealis var. purshii boreal wormwood G5T5 S1 A. campestris ssp. purshii Artemisia sp. -

NCDOT Invasive Exotic Plants

INVASIVE EXOTIC PLANTS OF NORTH CAROLINA Invasive Plants of North Carolina Cherri Smith N.C. Department of Transportation • 2008 Contents INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1: Threat to Habitat and Natural Areas . Trees........................................................................................................12 . Shrubs......................................................................................................20 . Herbaceous.Plants....................................................................................28 . Vines........................................................................................................44 . Aquatic.Plants..........................................................................................52 CHAPTER 2: Moderate Threat to Habitat and Natural Areas . Trees........................................................................................................60 . Shrubs......................................................................................................64 . Herbaceous.Plants....................................................................................78 . Vines........................................................................................................84 . Aquatic.Plants..........................................................................................96 CHAPTER 3: Watch List . Trees......................................................................................................104 -

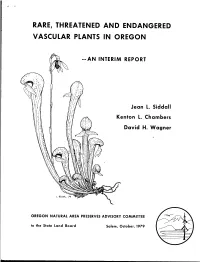

Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Vascular Plants in Oregon

RARE, THREATENED AND ENDANGERED VASCULAR PLANTS IN OREGON --AN INTERIM REPORT i •< . * •• Jean L. Siddall Kenton . Chambers David H. Wagner L Vorobik. 779 OREGON NATURAL AREA PRESERVES ADVISORY COMMITTEE to the State Land Board Salem, October, 1979 Natural Area Preserves Advisory Committee to the State Land Board Victor Atiyeh Norma Paulus Clay Myers Governor Secretary of State State Treasurer Members Robert E. Frenkel (Chairman), Corvallis Bruce Nolf (Vice Chairman), Bend Charles Collins, Roseburg Richard Forbes, Portland Jefferson Gonor, Newport Jean L. Siddall, Lake Oswego David H. Wagner, Eugene Ex-Officio Members Judith Hvam Will iam S. Phelps Department of Fish and Wildlife State Forestry Department Peter Bond J. Morris Johnson State Parks and Recreation Division State System of Higher Education Copies available from: Division of State Lands, 1445 State Street, Salem,Oregon 97310. Cover: Darlingtonia californica. Illustration by Linda Vorobik, Eugene, Oregon. RARE, THREATENED AND ENDANGERED VASCULAR PLANTS IN OREGON - an Interim Report by Jean L. Siddall Chairman Oregon Rare and Endangered Plant Species Taskforce Lake Oswego, Oregon Kenton L. Chambers Professor of Botany and Curator of Herbarium Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon David H. Wagner Director and Curator of Herbarium University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon Oregon Natural Area Preserves Advisory Committee Oregon State Land Board Division of State Lands Salem, Oregon October 1979 F O R E W O R D This report on rare, threatened and endangered vascular plants in Oregon is a basic document in the process of inventorying the state's natural areas * Prerequisite to the orderly establishment of natural preserves for research and conservation in Oregon are (1) a classification of the ecological types, and (2) a listing of the special organisms, which should be represented in a comprehensive system of designated natural areas. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Evolutionary Shifts Associated with Substrate Endemism in the Western American Flora Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/42f981n0 Author Schneider, Adam Publication Date 2017 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/42f981n0#supplemental Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Evolutionary Shifts Associated with Substrate Endemism in the Western American Flora By Adam Christopher Schneider A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Bruce Baldwin, Chair Professor Brent Mishler Professor Kip Will Summer 2017 Evolutionary Shifts Associated with Substrate Endemism in the Western American Flora Copyright © 2017 by Adam Christopher Schneider Abstract Evolutionary Shifts Associated with Substrate Endemism in the Western American Flora by Adam Christopher Schneider Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Bruce G. Baldwin, Chair This study investigated how habitat specialization affects the evolution and ecology of flowering plants. Specifically, a phylogenetic framework was used to investigate how trait evolution, lineage diversification, and biogeography of the western American flora are affected by two forms of substrate endemism: (1) edaphic specialization onto serpentine soils, and (2) host specialization of non-photosynthetic, holoparasitic Orobanchaceae. Previous studies have noted a correlation between presence on serpentine soils and a suite of morphological and physiological traits, one of which is the tendency of several serpentine-tolerant ecotypes to flower earlier than nearby closely related populations not growing on serpentine. -

Plant Fact Sheet for Oceanspray (Holodiscus Discolor)

Plant Fact Sheet browsed by cattle, deer, elk, snowshoe hares and OCEANSPRAY dusky-footed wood rats but not moose. As a common understory species, oceanspray provides cover for Holodiscus discolor (Pursh) numerous birds and small mammals and also Maxim. treefrogs. Seeds were eaten by Native Americans Plant Symbol = HODI who also used the hard straight stems for arrow, spear and harpoon shafts, halibut hooks, digging sticks and Contributed by: USDA NRCS Plant Materials sewing and knitting needles. Pioneers used the wood Center, Corvallis, Oregon as pegs in place of nails. Medicinally, an infusion of dried seed was used to treat diarrhea and prevent contagious diseases. A poultice of oceanspray bark and leaves was applied to burns or sores. Legal Status: Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g. threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description: Oceanspray is a moderately long-lived, moderately fast growing perennial shrub of the Rose family. It is native to western North America from British Columbia to southern California including areas of Montana, Colorado and Arizona. Multiple arching stems achieve 6 to 20 feet with the taller specimens found in shade or nearer the coast. The deciduous, alternate leaves are oval to triangular with deep veins and shallow lobes plus very fine teeth. They are green above and dull green beneath due to fine hairs and turn reddish in fall. Drooping, 4 to 7+ in. clusters of very small creamy white, sometimes pinkish flowers turn to beige then brown and often persist through winter.