Notes on the Bhagavad Gita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941. -

India's Ancient Culture

INDIA’S ANCIENT CULTURE SWAMI KRISHNANANDA The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org Publishers’ Note This book consists of a series of 21 discourses that Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj gave to students in The Divine Life Society's Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy from November 1989 to January 1990. Swamiji Maharaj begins with the earliest stages of Indian culture, and discusses its evolution until the highest level of human achievement, which is liberation of the soul by the realisation of Brahman, the Absolute, through the stages of samadhi. 2 Table of Contents Publishers’ Note………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Chapter 1: The Definition of Culture ............................................................................................ 4 Chapter 2: The Evolution of Culture .......................................................................................... 11 Chapter 3: The Vedas – the Foundation of Indian Culture .............................................. 1 Chapter 4: The Fourfold Aim of and How to Achieve It ............................... 2 8 Chapter 5: Introduction to the Epics ......................................................................................... 3 Life ............ 7 Chapter 6: the Ramayana and the Mahabharata ..................... 4 7 Chapter 7: The Message of the Mahabharata ........................................................................ 5 Similarities between 6 Chapter 8: India’s Concept of Totality ..................................................................................... -

Concept of Salvation in Hinduism

HINDUISM AND CONCEPT OF SALVATION {With special reference to The Bhagavad Gita} Tahira Basharat∗ The concept of salvation is present in almost all religions in its own distinct way. The primary purpose of all religions is to provide salvation to their followers and the existence of many different religions indicates that there is a great variety of opinion about what constitutes salvation and the means of achieving it. The term salvation can be meaningfully used in connection with so many religions, however, shows that it distinguishes a notion common to men and women of a wide range of cultural traditions. The monotheistic religions state that barrier between human and God is a sin. The monotheistic religions define salvation as entering a state of eternal communion with God, which means that personhood will not be abolished but perfected. However, they differ greatly on the way one can be saved and on the role Jesus Christ has in it. According to Judaism and Islam, salvation is attained by performing good deeds and following the moral law. According to Christianity this is not enough and the role of Jesus Christ as Savior is essential. Other Eastern religions, such as Buddhism and Taoism, take salvation as an illumination, meaning the discovery of and conformity of oneself with an eternal law that governs existence. Dualistic religions, which state that two opposed forces of good and evil rule our world, see salvation as a return to an initial angelic state, from which humans have fallen into a physical body. Salvation, for the Hindu, can be achieved in one of three ways: the way of works, the way of knowledge, or the way of devotion. -

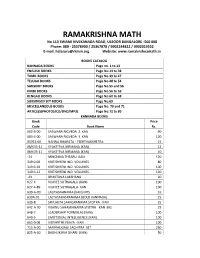

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Bhagavad Gita Free

öËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | é∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú-æËíŸæ “ Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ úŸ≤¤™‰ ™ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ | éÂ∆ƒºÎ ¿Ÿú ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ Ǩ∆Ÿ æËí¤ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº‰® æË⁄í≤Ÿ 韺Π∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿº ∫Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ºÎ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿Ÿ §-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸÅ ⁄∆úŸ≤™‰ | -⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿ËßThe‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤-í‹¡ºÎ ≤Ÿ¨ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%Bhagavad‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å Gita || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’-ÇŸYŸ {Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘®Ωæ Ã˘¤ æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰≥Æ˙-íË¿’ ≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ∆ || ¥˘ ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥The˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸº OriginalÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅSanskrit é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸºÎ ⁄“ º´—æ‰ —ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿Ë⁄“®¤ Ñ “‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºand Î ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§-⁄∆YŸº Å Ç—™‹ ™—ºÊ æ‰≤ Ü¥⁄Æ{Ÿ “§-æËí-⁄∆YŸ | ⁄∆∫˘Ÿú™‰ ¥˘Ë≤Ù™-¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇŸ¿Ëß‹ºÎ ÑôöËÅ Ç⁄∞¿ Ÿ ∏“‹-º™-±∆Ÿ≥™‰ ¿Ÿú-æËíºÎ ÇúŸ≤™ŸºÎ | “§-¥˘Æ¤⁄¥éŸºÎ ∞%‰ —∆Ÿ´ºŸ¿ŸºÅ é‚¥Ÿé¿Å || “§- An English Translation ≤Ÿ¨Ÿæ -

Essence of Sanatsujatiya of Maha Bharata

ESSENCE OF SANATSUJATIYA OF MAHA BHARATA Translated, interpreted and edited by V.D.N.Rao 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu, Matsya, Varaha, Kurma, Vamana, Narada, Padma; Shiva, Linga, Skanda, Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma, Brahma Vaivarta, Agni, Bhavishya, Nilamata; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa- Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama:a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri;b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata;c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima- Essence of Ashtaadasha Upanishads: Brihadarankya, Katha, Taittiriya/ Taittiriya Aranyaka , Isha, Svetashvatara, Maha Narayana and Maitreyi, Chhadogya and Kena, Atreya and Kausheetaki, Mundaka, Maandukya, Prashna, Jaabaala and Kaivalya. Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ - Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti -Essence of Brahma Sutras- Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students-Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and AusteritiesEssence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra; Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence -

Bhagavad Gita

BHAGAVAD GITA The Global Dharma for the Third Millennium Chapter Eight Translations and commentaries compiled by Parama Karuna Devi Copyright © 2012 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. Title ID:4173071 ISBN-13: 978-1482548471 ISBN-10: 148254847X published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center phone: +91 94373 00906 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com © 2011 PAVAN Chapter 8: Taraka brahma yoga The Yoga of transcendental liberation The 8th chapter of Bhagavad gita, entitled "The Yoga of liberating spiritual consciousness" takes us further into the central part of the discussion, focused on the development of bhakti - love and devotion for God. The topic of devotion is difficult to analyze because it deals with emotions rather than intellect and logic. However, devotion is particularly popular and powerful in changing people's lives, specifically because it works on people's feelings. Feelings and emotions fill up the life of a living being even on the material level and constitute the greatest source of joy and sorrow. All the forms of physical joys and sufferings depend on emotional joy and suffering: a different emotion in the awareness transforms hell into heaven, and heaven into hell. Attraction and attachment (raga) as well as repulsion and aversion (dvesa) are created by emotions, and these two polarities constitute the entire universe of material action and identification. It is impossible for a conditioned soul to ignore feelings or emotions, or to get rid of them. Usually, those who try to deny sentiments and emotions simply repress them, and we know that repressed sentiments and emotions become stronger and take deeper roots, consciously or unconsciously branching into a number of obsessive behaviors causing immense sufferings to the individual and to the people around him/her. -

Bhagavad Gita Mahayagna Batch 3 Journey

BHAGAVAD GITA MAHAYAGNA BATCH 3 JOURNEY THE DIVINE BEGINNINGS “Mantra Moolam Gurorvakyam” explains Lord Shiva to Goddess Parva; in the holy scripture of Guru Gita. The phrase means that the words uAered By a Guru is the source of mantra for a disciple. Thus, in July of 2015, when Parama Pujya Sri Ganapathy Sachchidananda Swamiji expressed a desire to listen to atleast 18 children memorize all 700 shlokas of Bhagavad Gita in a year’s ;me; it led to ini;a;on of a Mahayagna – A Bhagavad Gita Mahayagna. Since 2015, 240 + students (children and adults) have successfully memorized the Gita under 10 months or less and have also had the once in a life opportunity to offer their parayana to Parama Pujya Sri Swamiji in the Nada Mantapa - Mysore (Dec 2016, July 2017), Kurukshetra (Dec 2016) and Frisco - TX (July 2016, Dec 2017). BATCH 3 The Mahayagna program con;nued to gather steam in 2017, when new registra;ons Began for Batch 3. Wonderful alumni tes;monials and family experiences, amazing word of mouth via rela;ves and friends, Television and Newspaper coverage, puBlicity through social networking led to a record of over 400 par;cipants signing up for Batch 3 from 10 centers spanning different states in US and other countries as well. With Blessings from Parama Pujya Sri Swamiji and Sri Bala Swamiji classes Began in August 2017 across all centers. CLASSES, CAMPS & PERFORMANCES Based on the loca;on, students aAended classes either in-person, via conference calls or through Skype. Similar to previous Batches, Bi-weekly classes with weekly assessments were conducted for Batch 3. -

The Traces of the Bhagavad Gita in the Perennial Philosophy—A Critical Study of the Gita’S Reception Among the Perennialists

religions Article The Traces of the Bhagavad Gita in the Perennial Philosophy—A Critical Study of the Gita’s Reception Among the Perennialists Mohammad Syifa Amin Widigdo 1,2 1 Faculty of Islamic Studies, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Yogyakarta 55183, Indonesia; [email protected] 2 Wonderhome Library, Yogyakarta 55294, Indonesia Received: 14 April 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2020; Published: 6 May 2020 Abstract: This article studies the reception of the Bhagavad Gita within circles of Perennial Philosophy scholars and examines how the Gita is interpreted to the extent that it influenced their thoughts. Within the Hindu tradition, the Gita is often read from a dualist and/or non-dualist perspective in the context of observing religious teachings and practices. In the hands of Perennial Philosophy scholars, the Gita is read from a different angle. Through a critical examination of the original works of the Perennialists, this article shows that the majority of the Perennial traditionalists read the Gita from a dualist background but that, eventually, they were convinced that the Gita’s paradigm is essentially non-dualist. In turn, this non-dualist paradigm of the Gita influences and transforms their ontological thought, from the dualist to the non-dualist view of the reality. Meanwhile, the non-traditionalist group of Perennial Philosophy scholars are not interested in this ontological discussion. They are more concerned with the question of how the Gita provides certain ways of attaining human liberation and salvation. Interestingly, both traditionalist and non-traditionalist camps are influenced by the Gita, at the same time, inserting an external understanding and interpretation into the Gita. -

The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita

THE SACRED BOOKS OFTHEEAST Volume 8 SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST EDITOR: F. Max Muller These volumes of the Sacred Books of the East Series include translations of all the most important works of the seven non Christian religions. These have exercised a profound innuence on the civilizations of the continent of Asia. The Vedic Brahmanic System claims 21 volumes, Buddhism 10, and Jainism 2;8 volumes comprise Sacred Books of the Parsees; 2 volumes represent Islam; and 6 the two main indigenous systems of China. thus placing the historical and comparative study of religions on a solid foundation. VOLUMES 1,15. TilE UPANISADS: in 2 Vols. F. Max Muller 2,14. THE SACRED LAWS OF THE AR VAS: in 2 vols. Georg Buhler 3,16,27,28,39,40. THE SACRED BOOKS OF CHINA: In 6 Vols. James Legge 4,23,31. The ZEND-AVESTA: in 3 Vols. James Darmesleler & L.H. Mills 5, 18,24,37,47. PHALVI TEXTS: in 5 Vall. E. W. West 6,9. THE QUR' AN: in 2 Vols. E. H. Palmer 7. The INSTITUTES OF VISNU: J.Jolly R. THE BHAGA VADGITAwith lhe Sanalsujllliya and the Anugilii: K.T. Telang 10. THE DHAMMAPADA: F. Max Muller SUTTA-NIPATA: V. Fausbiill 1 I. BUDDHIST SUTTAS: T.W. Rhys Davids 12,26,41,43,44. VINAYA TEXTS: in 3 Vols. T.W. Rhys Davids & II. Oldenberg 19. THE FO·SHO-HING·TSANG·KING: Samuel Beal 21. THE SADDHARMA-PUM>ARlKA or TilE LOTUS OF THE TRUE LAWS: /I. Kern 22,45. lAINA SUTRAS: in 2 Vols. -

The Bhagavad Gita Translation by Shri Purohit Swami

TThhee BBhhaaggaavvaadd GGiittaa Translation by Shri Purohit Swami. This free PDF was downloaded from www.holybooks.com : http://www.holybooks.com/bhagavad-gita-three-modern-translations/ A NOTE ABOUT THE TRANSLATOR Shri Purohit Swami was born into a religious and wealthy family in Badners, India, in 1882. He studied philosophy and law, received his LL.B. from Decan College, Poona, married and had three children. However, he did not practice law, and instead spent his entire life in spiritual devotion. He wrote in his native Marathi, in Hindi, Sanskrit and English – poems, songs, a play, a novel, a commentary on The Bhagavad Gita and an autobiography. He left India in 1930 at the suggestion of his Master to interpret the religious life of India for the West, and made his new home in England. It was here that he produced beautiful translations of The Bhagavad Gita, Patanjali’s Aphorisms of Yoga and – in collaboration with his great friend, the Irish poet W.B. Yeats – The Ten Principal Upanishads. He died in 1946. This free PDF was downloaded from www.holybooks.com : http://www.holybooks.com/bhagavad-gita-three-modern-translations/ CONTENTS ONE: THE DESPONDENCY OF ARJUNA ................................................................................... 1 TWO: THE PHILOSOPHY OF DISCRIMINATION..................................................................... 4 THREE: KARMA-YOGA – THE PATH OF ACTION ................................................................... 9 FOUR: DNYANA-YOGA – THE PATH OF WISDOM............................................................... -

Essays in Life and Eternity

EESSSSAAYYSS IINN LLIIFFEE AANNDD EETTEERRNNIITTYY by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Preface 4 Introduction 5 Part I – Metaphysical Foundations 11 I - The Absolute And The Relative 11 II - The Universal And The Particular 13 III - The Cosmological Descent 15 IV - The Gods And The Celestial Heaven 17 V - The Human Individual 19 VI - The Evolution Of Consciousness 21 VII - The Epistemological Predicament 23 VIII - The World Of Science 25 IX - Psychology And Psychoanalysis 28 X - Aesthetics And The Field Of Beauty 31 Part II - The Social Scene 33 XI - The Phenomenon Of Society 33 XII - Axiology: The Aims Of Existence 35 XIII - The Nomative Features Of Ethics And Morality 37 XIV - Civic And Social Duty 40 XV - The Economy Of Life 43 XVI - Political Science And Administration 45 XVII - The Process Of History 48 XVIII - Education And Culture 51 Part III - The Development Of Religious Consciousness 54 XIX - The Inklings And Stages Of A Higher Presence 54 XX - The Exploration Of Reality 57 XXI - The Epics And Puranas 60 XXII - The Role Of Mythology In Religion 63 XXIII - The Ecstasy Of God-Love 65 XXIV - The Agama Sastra 67 XXV - Tantra Sadhana 69 XXVI - The Yoga-Vasishtha 72 Essays inin LifeLife andand EternityEternity by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 XXVII - Philosophical Proofs For The Existence Of God 75 XXVIII - Empirical Systems Of Philosophy 77 XXIX - The Mimamsa Doctrine Of Works 80 XXX