Northeast Parks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Manitoba Snowmobile Tourism Strategic Plan 2019-2023

Northern Manitoba Snowmobile Tourism Strategic Plan 2019-2023 February, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 NORTHERN MANITOBA SNOWMOBILE TOURISM ................................................................................. 2 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Relationship Among Plans ..................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Participants in the Snowmobile Tourism Summit................................................................................ 4 1.4 Approach to the Snowmobile Summit ................................................................................................ 6 2.0 HIGHLIGHTS OF SNOWMOBILING IN NORTH AMERICA ...................................................................... 7 2.1 History ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Market Dynamics ..................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2.1Manitoba Snowmobiling .............................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................... -

Meet Snow Lake's 2008 Grads

Sweet Nothings Please see us for giftware, souvenirs, jewelry, com- puter parts and service, Epicure, baby and bath items, flowers, pictures, and the work of a variety Providing business and residential High Speed Wireless Internet service to of local artists, artisans, musicians, and writers. Snow Lake and the surrounding area. Packages start as low as $27.95. Give us a call today and find out how we Open Tuesday to Friday from 12:00 to 5:00 p.m., Saturday from can hook you up with lightning fast High Speed Internet! 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Call toll free at 1-866-206-3707, E-mail: [email protected], or Check us out online: www.yourgiftideastore.com see our web page: http://www.gillamnet.com $1.00 NDERGROUND THE U PRESS Volume 12, Issue 12 Snow Lake Manitoba June 12, 2008 Meet Snow Lake's 2008 grads... AROUND TOWN • On June 5th, Judy Bishop ad- vised that her son had 103 days until he arrived home from his tour of duty in Afghanistan. She says that she misses him terribly, but he manages to call and email a lot when he is any- where with access. She also said he was saddened to hear of the recent loss of a member of his battalion, The Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, based at CFB Shilo. Noting that although he didn’t know Capt. Richard (Steve) Class of 2008: (L) Jenna Wiwcharuk-Roy, Dana Kowalchuk, Jace Ryan, Sheila Holmgren, Christina Walker, Brittany Ventura, and Danny Otto (Reclining). -

Wallace Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern

r Geology V f .ibrary TN 27 7A3V/1 WALLACE MINING AND MINERAL PROSPECTS IN NORTHERN MANITOBA THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES University of British Columbia D. REED LIBRARY The RALPH o DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ,-XGELES, CALIF. Northern Manitoba Bulletins Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern Manitoba BY R. C. WALLACE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF GOVERNMENT OP MANITOBA OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER OF NORTHERN MANITOBA The Pas, Manitoba Northern Manitoba Bulletins Mining and Mineral Prospects in Northern Manitoba BY R. C. WALLACE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF GOVERNMENT OF MANITOBA OFFICE OF COMMISSIONER OF NORTHERN MANITOBA The Pas, Manitoba CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Introductory 5 II. Geological features ... 7 III. History of Mining Development 12 IV. Metallic Deposits: (A) Mineral belt north of The Pas .... 20 (1) Flin Flon and Schist Lake Districts. .... ....20 (2) Athapapuskow Lake District ..... ....27 (3) Copper and Brunne Lake Districts .....30 (4) Herb and Little Herb Lake Districts .... .....31 (5) Pipe Lake, Wintering Lake and Hudson Bay Railway District... 37 (B) Other mineral areas .... .....37 V. Non-metallic Deposits 38 (a) Structural materials 38 (ft) Fuels 38 (c) Other deposits. 39 VI. The Economic Situatior 40 VII. Bibliography 42 Appendix: Synopsis of Regulations governing the granting of mineral rights.. ..44 NORTHERN MANITOBA NORTHERN MANITOBA Geology Library INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTORY Scope of Bulletin The purpose of this bulletin is to give a short description of the mineral deposits, in so far as they have been discovered and developed, in the territory which was added to the Province of Manitoba in the year 1912. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

The University of Manitoba the Author Reserves Other

TI{E T]VIPACT OF T'ORESTRY PFACTTCES oN MOosE (arces ar,cns) T}] NORTH - CENTRAL IVIANTTOBA by BARBA-RA E. SCATT'E A practícum submitted to the University of Manitoba an partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF NATURAL RESOT]RCE MANAGEMENT J drsao Permissi.on has been granted to the LTBRARy oF THE uNrvERsrry OF ì4ANITOBA to Lend or se,ll copies of this practicum, to the NATTONAL LTBRARY oF CANADA to mÍcrofilm this pracricum and to lend or sell copies of the film, and iJNrvERSrry I'frcROFrIìfs to publish an abstract of this practicum. The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the practicum nor extensive extracts from it uray be printed or otherwise reproduced vrithout the authorts r.¡ritten permission. -¡:l:i., i_l i'ì l ? i:: :,1 .,.-\ r.: .' .,; ' v.'j]-! I /-. ¡n r.-,r'lQ ':i ---i;t-- ABSTRÄ,CT The impact of forestry operations on moose (alces alces) in north - central Manitoba was determined through an examination of: (1) browse utilization by moose on forest cutovers, (2) spatial distribution of moose on forest cut- overs, and (3) hunter-kilI of moose in areas of pulpwood and timber extraction- An examination of the literature and the results of the browse and moose distribution surveys showed that forest har- vesting can be used to create moose habitat in Grass River provincial- Park. From these results, a series of guidelines regarding pulpwood and tj-mber extraction ín the study area were developed. The Provincial Park Lands Act provides Parks Branch with the legislation to regulate harvesting of trees in Grass River Provincial Park according to these guidelines. -

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a Foundation in Northern Manitoba

Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba Karla Zubrycki Dimple Roy Hisham Osman Kimberly Lewtas Geoffrey Gunn Richard Grosshans © 2014 The International Institute for Sustainable Development © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development | IISD.org November 2016 Large Area Planning in the Nelson-Churchill River Basin (NCRB): Laying a foundation in northern Manitoba © 2016 International Institute for Sustainable Development Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development International Institute for Sustainable Development The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is one Head Office of the world’s leading centres of research and innovation. The Institute provides practical solutions to the growing challenges and opportunities of 111 Lombard Avenue, Suite 325 integrating environmental and social priorities with economic development. Winnipeg, Manitoba We report on international negotiations and share knowledge gained Canada R3B 0T4 through collaborative projects, resulting in more rigorous research, stronger global networks, and better engagement among researchers, citizens, Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 businesses and policy-makers. Website: www.iisd.org Twitter: @IISD_news IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and from the Province -

Keeyask Generation Project: Aquatic Environment Supporting Volume

Keeyask Generation Project Environmental Impact Statement Supporting Volume Aquatic Environment June 2012 Morgan Bay100°W 95°W 90°W 60°N HUDSON Hudson Bay Settee Lake !( BAY Churchill ± Port Nelson Wei York !( r R Factory 55°N Thompson iver 55°N Deer Gillam Okaw Creek Island Island ER IV R N O S L E N 100°W 95°W 90°W Weir River Goose C Potential re e Conawapa G.S. k ÕÚ Lime Swift stone Riv er Creek VER Angling River RI S ! ÕÚ Limestone Fox Lake Cree Nation YE STEPHENS Fox Lake (Bird) G.S. Angling HA Kettle Lake ¾ÀPR 280 G.S. Proposed LAKE ÕÚ Keeyask G.S. ÕÚ Longspruce Clark ÕÚ Gillam! G.S. Fox Lake Cree Nation Lake NELSON RIVER A Kwis Ki Mahka Reserve Gull Lake ! Tataskweyak Cree Nation Tataskweyak (Split Lake) Assean Lake Burntwood River sonRiverEstuary_20120520.mxd SPLIT LAKE York Factory First Nation ! York Landing (Kawechiwasik) Kelsey G.S. Aiken River ! ÕÚ War Lake First Nation Ilford Fox River NELSON RIVER 0 25 50 Kilometres Projection: UTM Zone 15, NAD 83 Data Source: NTS base 1:500 000 Kelsey Generating Station to Nelson River Estuary 01020Miles File Location: G:\EIS\Keeyask\Publish_MXDs\SUPPORTING_VOLUME\REVISED_StillOldTemplate\Intro\AESV_1_KelseyGeneratingStationToNel Map 1-1 ke a L a ak w Mosw aio ak Wask ot rth o R N akot i v R osw er iver M h Sout 100°W 95°W 90°W 60°N Hudson Bay !( Churchill ± !( Thompson 55°N STEPHENS LAKE AREA 55°N S T E P Ferris H Bay 100°W 95°W 90°W E N S !( PR 280 ¾À LAKE Kettle G.S.ÚÕ Proposed KEEYASK AREA Keeyask G.S. -

Manitoba Anglers' Guide 2011 Manitobafisheries.Com

Manitoba Anglers' Guide 2011 manitobafisheries.com 2011_fishing_guide.indd 1 09/02/11 11:16 AM 2 | www.manitobafisheries.com As Manitoba’s Minister of Water Stewardship, I invite all anglers to experience our world-class fisheries and participate in the many programs Contents that promote the benefits of recreational angling What’s New for 2011....................................................................... 2 as a leisure activity. Pending & Possible Changes .........................................................2 My department is committed to partnering with Licences .......................................................................................... 3 anglers, stewardship groups, industry, and others Fees .......................................................................................3 with an interest in working to preserve angling as Exemptions ...........................................................................3 an important part of Manitoba’s heritage, now Outlets ..................................................................................3 and into the future. Through these partnerships, General Regulations .......................................................................3 Manitoba will continue to be one of the premier Fishing Methods ...................................................................3 recreational fishing destinations in North America. Barbless Hooks .....................................................................3 The Fisheries Enhancement Fund continues to build -

Finance Report 2015-2016

Finance Report 2015-2016 CONTENTS Message from the Director of Finance ............. 04 Finance Department Function ........................................................ 05 Objectives .................................................... 06 Meet our Team ...................................................... 07 Finance Information.............................................. 13 MFNERC Financial Statements .......................... 14 Independent Auditors’ Report .................. 15 Statement of Financial Position ................ 16 Statement of Operations ............................ 17 Statement of Changes in Net Assets ....... 18 Statement of Cash Flows ........................... 19 Notes to the Financial Statements ........... 20 Schedule 1 - Schedule of Revenue and Expenses - Administration ................. 27 Schedule 2 - Schedule of Revenue and Expenses - Roseau River Anishinabe First Nation Ginew School .............................................. 28 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF FINANCE On behalf of the MFNERC Board of Directors, we welcome Statements, which represents the highest standard for a you to preview our 2015-16 Financial Audit. Together we financial audit. value education. A positive educational process is our first priority. We are constantly looking for ways to work more The MFNERC received $4,654,331 from INAC under New efficiently, at the same time ensuring a quality education. Paths Program as well as $1,892,000 for Special Education and $1,359,850 for other Band Employee Benefits and This Audit report -

in the 1880S, Talk Had Begun of a Railway to Hudson Bay Through The

. In the 1880s, talk had begun of a railway to Hudson Bay through The Pas, which by then had become a commercial centre and steamship port supplying a growing number of settlements along the Saskatchewan River. It was the dream of farmers and businessmen _ a railway from The Pas to Hudson Bay and an ocean port. Construction of the line to The Pas was delayed until 1908, when the growing lumber industry generated enough commerce to warrant construction of a line to The Pas from the Canadian Northern main line. From that point on, The Pas was to become an important transportation link between southern Manitoba and the North. After the boundary division of 1912, the North became a part of Manitoba. There was a renewed interest in the region, not just as a source of furs, but as a source of timber, fish, minerals and precious metals. Gateway The opening of Mandy Mine (circa 1916) near Flin Flon secured The Pas' place as 'Gateway to the North,' and the town became the headquarters of northern mining, transportation and exploration. The discovery of the huge, rich copper/zinc discovery at Flin Flon (circa 1915) galvanized the entire area north of The Pas in a mining claim-staking frenzy. CV (Sonny) Whitney interests were willing to put up the millions required to construct a metallurgical complex at Flin Flon and a hydro generating station at Island Falls _ but a rail line to Flin Flon was essential to supply the undertaking. On December 17, 1927 an agreement was signed between the Province of Manitoba, Manitoba Northern Railway and Canadian National Railway to construct a line to Flin Flon 'for the purpose of developing Manitoba's resources.' The contract was awarded to Dominion Construction with a completion date of September 30, 1929. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2021-266

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2021-266 PDF version Ottawa, 5 August 2021 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Across Canada Various television and radio programming undertakings – Administrative renewals 1. The Commission renews the broadcasting licences for the television and radio programming undertakings set out in the appendix to this decision from 1 September 2021 to 31 March 2022, subject to the terms and conditions in effect under the current licences. The Commission also extends the distribution orders for the television programming undertakings CBC News Network, ICI RDI and ICI ARTV until 31 March 2022.1 2. In Broadcasting Decision 2020-201, the Commission renewed these licences administratively from 1 September 2020 to 31 August 2021, and extended the distribution orders for CBC News Network, ICI RDI and ICI ARTV until 31 August 2021. 3. This decision does not dispose of any issue that may arise with respect to the renewal of these licences. Secretary General Related documents Various television and radio programming undertakings – Administrative Renewals, Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2020-201, 22 June 2020 Distribution of the programming service of ARTV inc. by licensed terrestrial broadcasting distribution undertakings, Broadcasting Order CRTC 2013-375, 8 August 2013 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation – Licence renewals, Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2013-263 and Broadcasting Orders CRTC 2013-264 and 2013-265, 28 May 2013 This decision is to be appended to each licence. 1 For ICI RDI and CBC News Network, see Appendices 9 and 10, respectively, -

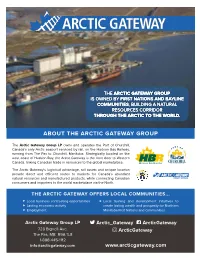

Arctic Gateway Media Backgrounder

THE ARCTIC GATEWAY GROUP IS OWNED BY FIRST NATIONS AND BAYLINE COMMUNITIES, BUILDING A NATURAL RESOURCES CORRIDOR THROUGH THE ARCTIC TO THE WORLD. ABOUT THE ARCTIC GATEWAY GROUP The Arctic Gateway Group LP owns and operates the Port of Churchill, Canada’s only Arctic seaport serviced by rail, on the Hudson Bay Railway, running from The Pas to Churchill, Manitoba. Strategically located on the west coast of Hudson Bay, the Arctic Gateway is the front door to Western Canada, linking Canadian trade in resources to the global marketplace. HUDSON BAY RAILWAY The Arctic Gateway’s logistical advantage, rail assets and unique location provide direct and efficient routes to markets for Canada’s abundant natural resources and manufactured products, while connecting Canadian consumers and importers to the world marketplace via the North. THE ARCTIC GATEWAY OFFERS LOCAL COMMUNITIES... Local business contracting opportunities Local training and development initiatives to Lasting economic activity create lasting wealth and prosperity for Northern Employment Manitoba First Nations and communities Arctic Gateway Group LP Arctic_Gateway ArcticGateway 728 Bignell Ave. ArcticGateway The Pas, MB R9A 1L8 1-888-445-1112 [email protected] www.arcticgateway.com PORT OF CHURCHILL trategically located on the west coast Open Water Days Per Year S of Hudson Bay, the Port of Churchill 200 Average Increase: 1.14 days/year brings Atlantic Ocean trade to the doorstep 180 of Western Canada. 160 The Port of Churchill offersfour deep-sea berths for loading 140 and unloading grain, manufactured, mining and forest 120 commodities, general cargo, and tanker vessels. Connected Season (Days) of Open Water Length to the rest of Canada via the Hudson Bay Railway, the Port 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 of Churchill is closer to 25% of Canada’s western grain production than any other port in the world.