Postminimalist Choral Music: a Pedagogical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All These Post-1965 Movements Under the “Conceptual Art” Umbrella

All these post-1965 movements under the “conceptual art” umbrella- Postminimalism or process art, Site Specific works, Conceptual art movement proper, Performance art, Body Art and all combinations thereof- move the practice of art away from art-as-autonomous object, and art-as-commodification, and towards art-as-experience, where subject becomes object, hierarchy between subject and object is critiqued and intersubjectivity of artist, viewer and artwork abounds! Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, Conceptual Body art, Postmodern beginning “As opposed to being viewers of the work, once again they are viewers in it.” (“Subject as Object,” p. 199) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IrqXiqgQBo A Postmodern beginning: Body art and Performance art as critique of art-as-object recap: -Bruce Nauman -Vito Acconci focus on: -Chris Burden -Richard Serra -Carolee Schneemann - Hannah Wilke Chapter 3, pp. 114-132 (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, First Generation Feminism) Bruce Nauman, Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, 1967-1968. 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 10 min. Body art/Performance art, Postmodern beginning- performed elementary gestures in the privacy of his studio and documented them in a variety of media Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969, Body art, Performance art- outside the studio, Postmodern beginning Video documentation of the event Print made from bite mark Vito Acconci, Trademarks, 1970, Body art, Performance art, Postmodern beginning Video and Print documentation -

The Present Position of Authenticity

Performance Practice Review Volume 2 Article 2 Number 2 Fall The rP esent Position of Authenticity Robert Donington Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Donington, Robert (1989) "The rP esent Position of Authenticity," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 2: No. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.198902.02.2 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol2/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. On Behalf of Historical Performance The Present Position of Authenticity Robert Donington Not for the first time, the great divide is opening up between those of us, such as the readers of this Review, who aspire to authenticity in performing early music, and those others who argue, on the contrary, that authenticity is either unattainable or undesirable or both. It is also possible to take up a middle position, allowing for a measure of compromise adjusted to the practical circumstances of a given situation. But even so, it is the basic orientation of the performer which really counts. The effect of it is by no means merely theoretical. The differences in performing practice at the present time are startling, and their significance for every variety of our musical experience is growing all the time. It is not only for early music that the issue is getting to be so very topical. -

![Superimposed Subdivisions (Polyrhythm Hell) [Sallan Tarkistama]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6794/superimposed-subdivisions-polyrhythm-hell-sallan-tarkistama-226794.webp)

Superimposed Subdivisions (Polyrhythm Hell) [Sallan Tarkistama]

HEIKKI MALMBERG Superimposed Subdivisions (Polyrhythm Hell) Polyrhythms or Polymeters? Usually when musicians talk about polyrhythms, they refer to rhythmic structures that are made of two or more simultaneous time signatures, in which the secondary (superimposed) time signature basically revolves around the dominant time signature. I suggest that we use the term polymeter in such cases, and use the term polyrhythm solely in situations where there are two or more subdivisions happening in the same time interval (e.g. eight note triplets over sixteenth notes). Here’s a simple example of a polymeter where the bass drum plays in 5/16 while the hands keep common (4/4) time. 3 3 3 3 5 5 5 5 5 5 3 5 5 5 5 And here’s a not so simple example of polyrhythms using eight notes, eight/quarter note triplets and sixteenth note quintuplets. So What Should I Do? In order to learn to play any two subdivisions against each other, or rather superimpose them if you will, you should get a reference of how they sound played simultaneously on one instrument (A good teacher and a sequencer are of paramount help here), and learn to phonetically mimic the result. You can make up halfwitted sentences or just blabber away with any foolish sounds that you come up with. as long as you’re mimicking the rhythm, it doesn’t matter. 3 3 3 3 or cold cup of tea blah bla da blah Here’s two subdivisions Here they have Here’s their daily dialog after waiting to get married. -

8Th Annual Gamut Conference Program

The Graduate Association of Musicologists und Theorists presents the 8th annual GAMuT Graduate Student Conference Saturday, February 6, 2021, 9:00am–5:45pm CST Held via Zoom, University of North Texas Keynote Speaker: Olivia Bloechl (University of Pittsburgh) “Doing Music History Where We Are” Generously Supported by The Division of Music History, Theory, and Ethnomusicology Program 9:00 Welcome and Opening remarks Peter Kohanski, GAMuT President/Conference Co-Chair Benjamin Brand, PhD, Professor of Music History and Chair of the Division of Music History, Theory, and Ethnomusicology 9:15 Race and Culture in the Contemporary Music Scene Session Chair: Rachel Schuck “Sounds of the 'Hyperghetto': Sounded Counternarratives in Newark, New Jersey Club Music Production and Performance” Jasmine A. Henry (Rutgers University) “‘I Opened the Lock in My Mind’: Centering the Development of Aeham Ahmad’s Oriental Jazz Style from Syria to Germany” Katelin Webster (Ohio State University) “Keeping the Tradition Alive: The Virtual Irish Session in the time of COVID-19” Andrew Bobker (Michigan State University) 10:45 Break 11:00 Reconsidering 20th-Century Styles and Aesthetics Session Chair: Rachel Gain “Diatonic Chromaticism?: Juxtaposition and Superimposition as Process in Penderecki's Song of the Cherubim” Jesse Kiser (University of Buffalo) “Adjusting the Sound, Closing the Mind: Foucault's Episteme and the Cultural Isolation of Contemporary Music” Paul David Flood (University of California, Irvine) 12:00 Lunch, on your own 1:00 Keynote Address Session -

Centenary Celebration Report

Celebrating 100 years CHOIR SCHOOLS’ ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE 2018 Front cover photograph: Choristers representing CSA’s three founding member schools, with lay clerks and girl choristers from Salisbury Cathedral, join together to celebrate a Centenary Evensong in St Paul’s Cathedral 2018 CONFERENCE REPORT ........................................................................ s the Choir Schools’ Association (CSA) prepares to enter its second century, A it would be difficult to imagine a better location for its annual conference than New Change, London EC4, where most of this year’s sessions took place in the light-filled 21st-century surroundings of the K&L Gates law firm’s new conference rooms, with their stunning views of St Paul’s Cathedral and its Choir School over the road. One hundred years ago, the then headmaster of St Paul’s Cathedral Choir School, Reverend R H Couchman, joined his colleagues from King’s College School, Cambridge and Westminster Abbey Choir School to consider the sustainability of choir schools in the light of rigorous inspections of independent schools and regulations governing the employment of children being introduced under the terms of the Fisher Education Act. Although cathedral choristers were quickly exempted from the new employment legislation, the meeting led to the formation of the CSA, and Couchman was its honorary secretary until his retirement in 1937. He, more than anyone, ensured that it developed strongly, wrote Alan Mould, former headmaster of St John’s College School, Cambridge, in The English -

Timbre and Tintinnabulation in the Music of Arvo Part

Timbre and Tintinnabulation in the Music of Arvo Part WONG Hoi Sze Susanna A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Music ©The Chinese University of Hong Kong September 2001 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. •( 13 APR m )1) ^^IBRARY SYSTEMX^ Abstract of thesis entitled: Timbre and Tintinnabulation in the Music of Arvo PM Submitted by Wong Hoi Sze Susanna for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Music at The Chinese University of Hong Kong in June 2001 Arvo Part (born 1935), one of the most outstanding Estonian composers, studied composition at the Tallinn Conservatory, graduating in 1963. He first gained recognition in Soviet Russia in 1959 with his prize-winning tonal cantata for children - Meie Aed (Our Garden). In the following year, he started experimenting with aspects of serialism and, later, with combining several styles in one piece. Although the Soviet authorities criticized his experimental music, he continued to compose serial works until 1968. After that he stopped composing for almost eight years. During this self-imposed compositional silence, he immersed himself in the intensive study of medieval and Renaissance music, for example, Gregorian chant, the music of Machaut, Ockeghem and Josquin. He eventually developed a distinctive compositional style, which he calls the "tintinnabuli style." Fur Alina (1976), a short piano solo, was his first tintinnabuli work. -

Choral Evensong

Summer 2017 Service & Music List Sunday 2nd July The Third Sunday after Trinity Thursday 6th July Decani Week 11.05am Eucharist said in Saint Stephen’s Chapel 9.15am Eucharist said in the Lady Chapel 5.30pm Choral Evensong sung by the Georgia Boys’ Choir 11 .15 am Choral Eucharist sung by the Maryland State Boy choir Canticles Brewer in D Responses: Hancock Setting Piccolo: Canterbury Mass Anthem All in the April evening Roberton Psalm: 34 vv 1 -10 Gradual O sing joyfully Batten Motet Ave Verum corpus Byrd Friday 7th July Preacher The Revd T.S. Forster, B.A., B.Th., M.Phil. 5.30pm Choral Evensong sung by the Georgia Boys’ Choir Prebendary of Yagoe Hymns: 334, 272, 475 3.15pm Choral Evensong sung by the Maryland State Boy choir Canticles Kelly in C Responses: Hancock Anthem Like as the hart Howells Psalm: 37 vv 1 -11 Canticle s Stanford in C Responses: Quinn An them Hail gladdening light Wood Psalm: 12 Saturday 8th July Voluntary Preludium in G Buxtehude Hymns: 483 (t.77), 252 11.05am Eucharist said in Saint Stephen’s Chapel rd Monday 3 July Saint Thomas th 5.30pm Choral Evensong sung by the Georgia Boys’ Choir Sunday 9 July The Fourth Sunday after Trinity Cantoris Week Canticles Dyson in D Re sponses: Hancock Anthem The deer’s cry Pärt Psalm: 18 vv 1 -16 9.15am Eucharist said in the Lady Chapel 11.15am Choral Eucharist sung by the Georgia Boys’ Choir Tuesday 4th July Setting Missa de Angelis 5.30pm Choral Evensong sung by the Georgia Boys’ Choir Gradual Os Justi Bruckner Motet Faire is th e Heaven Harris Canticles Hogan in D b Responses: Hancock Preacher The Revd W.P. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to. -

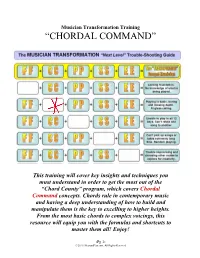

“Chordal Command”

Musician Transformation Training “CHORDAL COMMAND” This training will cover key insights and techniques you must understand in order to get the most out of the “Chord County” program, which covers Chordal Command concepts. Chords rule in contemporary music and having a deep understanding of how to build and manipulate them is the key to excelling to higher heights. From the most basic chords to complex voicings, this resource will equip you with the formulas and shortcuts to master them all! Enjoy! -Pg 1- © 2010. HearandPlay.com. All Rights Reserved Introduction In this guide, we’ll be starting with triads and what I call the “FANTASTIC FOUR.” Then we’ll move on to shortcuts that will help you master extended chords (the heart of contemporary playing). After that, we’ll discuss inversions (the key to multiplying your chordal vocaluary), primary vs secondary chords, and we’ll end on voicings and the difference between “voicings” and “inversions.” But first, let’s turn to some common problems musicians encounter when it comes to chordal mastery. Common Problems 1. Lack of chordal knowledge beyond triads: Musicians who fall into this category simply have never reached outside of the basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) and are stuck playing the same chords they’ve always played. There is a mental block that almost prohibits them from learning and retaining new chords. Extra effort must be made to embrace new chords, no matter how difficult and unusual they are at first. Knowing the chord formulas and shortcuts that will turn any basic triad into an extended chord is the secret. -

Postmodern Art and Its Discontents Professor Paul Ivey, School of Art [email protected]

Humanities Seminars Program Fall 2014 Postmodern Art and Its Discontents Professor Paul Ivey, School of Art [email protected] This ten week course examines the issues, artists, and theories surrounding the rise of Postmodernism in the visual arts from 1970 into the twenty-first century. We will explore the emergence of pluralism in the visual arts against a backdrop of the rise of the global economy as we explore the “crisis” of postmodern culture, which critiques ideas of history, progress, personal and cultural identities, and embraces irony and parody, pastiche, nostalgia, mass or “low” culture, and multiculturalism. In a chronological fashion, and framed by a discussion of mid-century artistic predecessors Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and Minimal Art, the class looks at the wide-ranging visual art practices that emerged in 1970s Conceptual Art, Performance, Feminist Art and identity politics, art activism and the Culture Wars, Appropriation Art, Neo-expressionism, Street Art, the Young British Artists, the Museum, and Festivalism. Week 1: October 6 Contexts and Setting the Stage: What is Postmodernism Abstract Expressionism Week 2: October 13 Cold War, Neo-Dada, Pop Art Week 3: October 20 Minimalism, Postminimalism, Earth Art Week 4: October 27 Conceptual Art and Performance: Chance, Happenings, Arte Povera, Fluxus Week 5: November 3 Video and Performance Week 6: November 10 Feminist Art and Identity Politics Week 7: November 17 Street Art, Neo-Expressionism, Appropriation Week 8: December 1 Art Activism and Culture Wars Week 9: December 8 Young British Artists (YBAs) Week 10: December 15 Festivalism and the Museum . -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen's Mikrophonie I and Saariaho's Six Japanese Gardens Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9b10838z Author Keelaghan, Nikolaus Adrian Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen‘s Mikrophonie I and Saariaho‘s Six Japanese Gardens A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan 2016 © Copyright by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen‘s Mikrophonie I and Saariaho‘s Six Japanese Gardens by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Robert Winter, Chair The origins of electroacoustic music are rooted in a long-standing tradition of non-human music making, dating back centuries to the inventions of automaton creators. The technological boom during and following the Second World War provided composers with a new wave of electronic devices that put a wealth of new, truly twentieth-century sounds at their disposal. Percussionists, by virtue of their longstanding relationship to new sounds and their ability to decipher complex parts for a bewildering variety of instruments, have been a favored recipient of what has become known as electroacoustic music. -

Choir School News • 3 Memories of John Scott from the Choir School Community

Can- Dom- tate ino Choir School News A Newsletter for Alumni & Friends of Saint Thomas Choir School WINTER/SPRING 2016 ©2016 Studios Ira Lippke John Gavin Scott (1956-2015) This edition of the Choir School News is in thanksgiving for the life and witness of John Scott. Here, alumni, parents, colleagues and friends share memories and reflections of his extraordinary impact on this community. Through John’s gifts, people not only experienced music of the highest caliber, but were also drawn deeper into the mystery of God. For all of us, John’s death was a terrible shock. It has caused us to reflect on how fragile life can be. Even as we have moved forward at the Choir School, we continue to miss him and entrust him to God’s care and protection. I invite you to share in our common life through these pages. –Charles F. Wallace, Headmaster IN MEMORIAM EXCERPTS FROM FATHER MEAD’S HOMILY AT JOHN SCOTT’S FUNERAL Evensong and a recital of Buxtehude. I asked John, who was then forty-seven but had been at St. Paul’s since his mid-twenties, would he be interested in coming to Saint Thomas? He would be interested, he replied, but that if I would please understand he would like not to have to apply. Very well; would he give me his resume? Yes, he would. This was pure John. As John prepared to leave St. Paul’s, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth made him a Lieutenant of the Victorian Order (LVO) for his distinguished services to the Crown at London’s great cathedral, where John led the music for many royal and state occasions – not to mention the daily round of choral evensongs and other liturgies.