A Sourcebook for Nevada Policymakers This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delegate Manual

AN IMPORTANT NOTE: ONLINE PROGRAMS ............................ 3 PROGRAM OVERVIEW .................................................................. 4 Introduction 4 Boys’ State History 4 American Legion 5 Boys’ Nation 5 Nevada Boys’ State Governors 5 Nevada Boys’ State Alumni Association 5 Staff 6 Nevada Boys’ State Hall of Fame 6 The Future of Nevada Boys’ State 6 PROGRAM PREPARATION ........................................................... 7 What to Bring 7 Legislation Submission 8 NEVADA BOYS’ STATE STRUCTURE ......................................... 9 Rules Pertaining to Political Office 9 Political Parties 9 Party Committees 10 Recommended Party Platform 12 The City 13 The State 14 The Judiciary: Moot Court 15 The Judiciary: Nevada Boys’ State Statutes 16 Elected Positions & Conflict Chart* 19 The Boys’ State Monetary System 21 LEGISLATIVE PROCESS ............................................................... 22 Introduction 22 Bills 22 Submitting and Writing a Bill Online 24 Committees 25 Standing Rules and Procedures of the Senate and Assembly 26 How a Bill Becomes a Law: Graphical Representation 27 The Ten Principles 28 Types of Motions 28 Five Steps to Every Motion 28 Methods of Voting on a Motion 29 Table of Motions 30 PROGRAM THEME ........................................................................ 31 What is Leadership? 31 United States Flag Code 32 DAILY HONORS ............................................................................. 33 Boys’ State Creed 33 Resolution 288 33 Songs 33 CODE OF CONDUCT .................................................................... -

Walker Lake a Delicate Balance

Once Nevada, Always Nevada • Fall 2007 TOP SCHOLARS SHINE AT NEVADA STATECOE SENATOR SWOBE WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE WALKER LAKE A delicate balance LATINO BUSINESS OWNERS STRUGGLE, BUT THRIVE MARY-ELLEN MCMULLEN ALUMNA OF THE YEAR REMEMBERS STUDENT DayS Like the University’s founders who planted a quadrangle of trees BENEFITS OF MEMBERSHIP at the heart of campus so many years ago… your generosity and • Listing in the Annual foresight will provide for an environment where great minds will thrive. Honor Roll of Donors and other publications (with permission) • Invitation to Annual Gratitude Event on campus • Nevada Legacy Society certificate and lapel pin • As a member of the Nevada Legacy Society you can choose where funds will be applied. AREAS IN NEED OF University Quadrangle, late 1800s. SUppORT INCLUDE: On behalf of the Foundation, we are pleased to announce the creation of the • Endowed student scholarships based on criteria set by the donor Nevada Legacy Society. • Innovative academic programs that prepare The society was formed to recognize and honor the commitment of those who have provided for students for 21st century the future support of the University under their estate or financial plans — regardless of the size of challenges the gift. • Lecture series that feature The launch of our Legacy Society also brings new opportunities to share examples of how an scientists, scholars, artists, individual can make a difference. Your confidence and investment is critical to securing Nevada’s and other leaders future, and we are grateful to be able to thank you now! • Professorships, chairships, If you have included the University of Nevada, Reno Foundation in your bequest, insurance policy, deanships and other trust or other planned gift, we would appreciate you contacting development programs us and letting us list your name in the future among others who to recruit the best faculty have provided resources to the Foundation. -

Section IX the STATE PAGES

Section IX THE STATE PAGES THE FOLLOWING section presents information on all the states of the United States and the District of Columbia; the commonwealths of Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands; the territories of American Samoa, Guam and the Virgin Islands; and the United Na tions trusteeships of the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and the Republic of Belau.* Included are listings of various executive officials, the justices of the supreme courts and officers of the legislatures. Lists of all officials are as of late 1981 or early 1982. Comprehensive listings of state legislators and other state officials appear in other publications of The Council of State Governments. Concluding each state listing are population figures and other statistics provided by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, based on the 1980 enumerafion. Preceding the state pages are three tables. The first lists the official names of states, the state capitols with zip codes and the telephone numbers of state central switchboards. The second table presents historical data on all the states, commonwealths and territories. The third presents a compilation of selected state statistics from the state pages. *The Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and the Republic of Belau (formerly Palau) have been administered by the United Slates since July 18, 1947, as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPl), a trusteeship of the United Nations. The Northern Mariana Islands separated themselves from TTPI in March 1976 and now operate under a constitutional govern ment instituted January 9, 1978. -

10262020 Marketing Committee Minutes

Nevada Commission on Tourism | Marketing Committee October 26, 2020 | Minutes NEVADA COMMISSION ON TOURISM Marketing Committee Monday, October 26, 2020 The Nevada Commission on Tourism held a Marketing Committee meeting at 1 p.m. on October 26, 2020 via Zoom. Call to Oder Fletch Brunelle, Chair, called the meeting to order at 1 p.m. Committee Members Present Carl Ribaudo Christina Erny Cynthia Mun Deny Dotson Fletch Brunelle Committee Member Absent/Excused N/A Staff Present Brenda Scolari Christian Passink Jessica Grundy Kyle Shulz M.E. Kawchack Tracie Barnthouse Guests Present Fahlgren Mortine Noble Studios Meeting BRUNELLE: Good afternoon, everyone. I'd like to call to order the Marketing Subcommittee meeting of the Nevada Commission on Tourism. It's October 26, 2020 at 1:00 PM, sharp. Can you please confirm that this meeting was properly noticed and posted? GRUNDY: This is Jessica Grundy. Yes, it was. BRUNELLE: All right. Thank you. M.E., can you please call roll? KAWCHACK: I can. Thank you. Fletch Brunelle. BRUNELLE: Here. KAWCHACK: Christina Erny. ERNY: Here. KAWCHACK: Carl Ribaudo. P a g e 1 | 34 Nevada Commission on Tourism | Marketing Committee October 26, 2020 | Minutes RIBAUDO: Here. KAWCHACK: Deny Dotson. DOTSON: Here. KAWCHACK: Cynthia Mun. MUN: Here. KAWCHACK: Great. We have a quorum. Thank you. BRUNELLE: Let's move to item B public comments. Is anyone on the call for public comments? GRUNDY: I don't think so. BRUNELLE: Okay. With that, let's move to agenda item C, approval of minutes. This is for July 28, 2020 meeting. Are there any proposals by way of motion for any matter relating to those minutes? If not, I'll entertain a motion to approve those minutes. -

The A-MAZE-Ing State Game

The A-MAZE-ing State Game A Quilt, Table Cloth, or Play Rug (for a Children’s Game Room or Classroom) Project Designer: Flora and Henry Joy (www.storytellingworld.com) Information sources: A vast variety of Internet sites and reference materials Assistants: Sharon Crowe, Marc Montgomery, Meg Foster, and Nancy Kavanaugh The information on the following pages provides details regarding how to get and use “The A-MAZE-ing State Game” for your home, classroom, or other educational or fun setting. To GET the game, do the following: --Print Section 1 (Page 3) of this packet and follow the steps in ordering the fabric for this project. OR hand that sheet to someone who truly wishes to assist you in your endeavors to help children with their academic skills, and ask that person if he/she would order this panel of fabric and “donate” it to your classroom/home. --After you have received the fabric, print Section 2 (page 4) and make the game. If you can’t sew (only the very basic sewing skills are needed), give the fabric (with the printed page) to someone who CAN SEW, and ask him/her to consider making the quilt for your cause. If THAT person can’t do so, continue until you have found someone who WILL. If all else fails, go to your local quilt shop and inquire about hiring someone to put this project together. [This can be made QUICKLY, depending upon the amount of embellishment (if any) that is chosen.] Anyone who can stitch a straight seam (and who has a sewing machine) can stitch together this quilt. -

2Nd Qtr FY2020 Payment Worksheet

Washoe County, Nevada Quarterly Report of Payments by Payee for the Period 7/1/2019 ‐ 12/31/2019 Note: certain payees have been grouped by type of payment due to confidentiality or one‐time small payment size. VENDOR 2ND QTR Year to Date 1 800 BOLLARDS$ 1,171.88 $ 1,171.88 1 800 GOT JUNK ‐ 238.00 1788 INC. 4,941.72 28,557.33 2018‐3 IH BORROWER LP ‐ 1,532.00 24 SEVEN 103.25 103.25 3 ANGELS CARE 284,165.00 556,695.00 3 WAY OF NEVADA 200.00 200.00 3D CONCRETE INC. 208.00 208.00 3M COMPANY ‐ SIGNS 16,529.37 16,529.37 49ER COMMUNICATIONS ‐ 1,057.70 4IMPRINT INC 1,363.92 3,233.35 601 W MOANA LLC 5,622.00 16,866.00 7‐ELEVEN 58.54 214.09 8000 OFFENHAUSER OWNER LLC ‐ 1,852.00 8200 OFFENHAUSER OWNER LLC 1,274.00 1,274.00 911 MARKET LTD 132.80 132.80 99 CENTS ONLY STORES 819.23 1,260.17 A & B PRINTING & MAILING 4,699.17 9,171.55 A & L LAMINATING 348.75 1,187.90 A AND H INSURANCE, INC. 50.00 50.00 A BRIDGE FOR AFRICA 860.50 860.50 A CARLISLE & COMPANY 3,297.00 3,297.00 A CHILDS WORLD 536.60 1,109.60 A GR8 START 1,360.00 1,360.00 A STEP AHEAD 693.00 693.00 A&K EARTH MOVERS INC 2,103.75 2,103.75 A+ LEARNING CENTER ‐ 1,080.00 A1 NATIONAL FIRE CO LLC 1,459.12 2,031.95 A‐1 TRANSMISSION INC 1,582.55 11,381.85 A‐AMERICAN SELF STORAGE MANAGEMENT COMPANY INC 952.00 1,666.00 ABACUS DIAGNOSTICS INC 581.81 581.81 ABBOTT NUTRITION INC ‐ 25.00 ABBOTT, DONNA 160.00 400.00 ABC‐NV 276.00 276.00 ABERASTURI, SUZANNE 12,100.00 18,700.00 ABILITY BUILDING CENTER 189.08 189.08 ABSOLUTE DENTAL ‐ 1,152.28 ABSOLUTE DRAIN SERVICE 4,400.00 4,545.00 ABSOLUTE HOSE AND FITTINGS -

Winter 2010 Winter the Magazine of the University of Nevada, Reno • Reno Nevada, of University the of Magazine the Y TH TH U Ur Wa Ur Yo Ming Ming

The magazine of the University of Nevada, Reno • Winter 2010 becoming global citizens: The world is our campus NEVADA SILVER & BLUE Sara Lafrance Global Educator • Winter 2010 2010 Summer YOuTH campS cOming your waY From the President International education: Pathway to a more connected world Back in the 16th century, the essayist Michel de Montaigne got it right when he wrote about the value of interacting with the rest of the world. Montaigne believed that to see only within the borders of one’s country was to be intellectually self-limiting. When we seek out experiences and The magazine of the University of Nevada, Reno perspectives that go well beyond our borders, we afford ourselves of a great opportunity, which he www.unr.edu/silverandblue described as the ability to “rub and sharpen our minds against others.” Copyright ©2009, by the University of Nevada, Reno. All It’s interesting that Montaigne wrote those words rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without in the pre-Thomas Friedman, pre-“World Is Flat,” written permission is prohibited. Nevada Silver & Blue (USPS# pre-Internet, pre-global economy days of the French Danna-Douglas Theresa by Photo 024-722), Winter 2010, Volume 26, Number 2, is published Renaissance. Carmelo Urza, director of USAC, President quarterly (winter, spring, summer, fall) by the University of Nevada, Reno, Development and Alumni Relations, Morrill Yet, his words ring with an even more singular Glick and Susan Bender, director of the Office Hall, 1664 N. Virginia St., Reno, NV 89503-2007. Periodicals resonance today—particularly for college campuses. -

State to State Comparisons 2017 Nh Nv

STATE TO STATE COMPARISONS 2017 NH NV TAXES Corporate Income Tax Rate 8.2% * 0.0% Apportionment Formula Property Factor 25% N/A Payroll Factor 25% N/A Sales Factor 50% 100% Throwback Rule Yes No NOL Deductions Carryback (Years) 0 N/A Carryforward (Years) 10 N/A LLCs Recognized No Yes S-corps Recognized No Yes Sales Tax & Use Tax % None 6.9 Internet Sales Tax None 6.5 Tax Exemptions Manufacturing Machinery No Tax Taxable Office Equipment No Tax Taxable Custom Software No Tax Exempt Modified Canned Software No Tax Taxable Tangible Personal Property No Tax Taxable Sales & Use - Weighted Average of County & City Rates No Tax 0.0 Top Personal Income Tax % 0% 0.0 Professional Services Tax N N Estate, inheritance/gift taxes beyond fed. Pick-up tax. N N Motor Fuel Tax, 11 0.196 0.331 Property Tax On Land & Buildings, as share of personal income 5.496 2.9 Telecommunications Tax % State/Local SalesTax 0.00 7.79 State/Local Wireless Rate 8.17 1.86 Workers Compensation Premium Index Rate 2.2 1.3 Unemployment Insurance Tax % (New Employers), 16 2.70 2.95 Unemployment Insurance Time Period to Qualify for Experience Rating 0.05 0.25 Unemployment Insurance Tax Wage Bases, 16 $14,000 $28,200 Unemployment Insurance Tax/ Per Employee, 16 $308 $832 Unemployment Insurance Number of Benefit Weeks 26 12 to 26 State Trust Fund negative loan balance to Federal Gov. (April, 2015) 0.00 0.00 Gasoline Excise Tax (cents per gallon) 22.2 23.0 Diesel Excise Tax (cents per gallon) 22.2 27.0 Tobacco Excise Tax (cents per pack of 20) 1.8 1.8 State Taxes as Percentage of Personal Income 8.0% 8.1% Small Business Tax Index: 2014 (1= Best 50= Worst) 18 1 Tax Climate Index (U.S. -

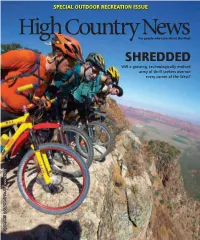

SHREDDED Will a Growing, Technologically Evolved Army of Thrill Seekers Overrun Every Corner of the West? July 20, 2015 | $5 | Vol

SPECIAL OUTDOOR RECREATION ISSUE High Country ForN people whoews care about the West SHREDDED Will a growing, technologically evolved army of thrill seekers overrun every corner of the West? July 20, 2015 | $5 | Vol. 47 No. 12 | www.hcn.org 12 No. 47 | $5 Vol. 20, 2015 July CONTENTS High Country News EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR/PUBLISHER Paul Larmer MANAGING EDITOR Brian Calvert SENIOR EDITORS Jonathan Thompson SHREDDED Jodi Peterson ART DIRECTOR Will a growing, technologically evolved army of Cindy Wehling thrill seekers overrun every corner of the West? ONLINE EDITOR Tay Wiles D.C. CORRESPONDENT SPECIAL OUTDOOR RECREATION ISSUE Elizabeth Shogren WRITERS ON THE RANGE EDITOR Betsy Marston ASSOCIATE DESIGNER Brooke Warren FEATURES/ESSAYS COPY EDITOR Diane Sylvain CONTRIBUTIng EDITORS 14 End of the Trail Wars Cally Carswell As a decades-long battle between a tribe of local mountain bikers Craig Childs Sarah Gilman and the Forest Service dies down, Sedona faces the end of its Judith Lewis Mernit By Sarah Tory Jeremy Miller free-wheeling era. Sierra Crane-Murdoch Michelle Nijhuis 36 The Human Factor Josh Zaffos CORRESPONDENTS We’re better than ever at understanding the dangers of avalanches. Ben Goldfarb So why aren’t we better at avoiding them? By Kate Siber Krista Langlois Kate Schimel 44 Knowing the Grand Canyon in your bones EDITORIAL FELLOW By Nic Korte Sarah Tory INTERNS Paige Blankenbueler 46 #OutdoorRec and #Tech Gloria Dickie How do our electronic gadgets, social media platforms and ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Alexis Halbert constant connectedness -

MUSICAL HORN SONG LIST.Pdf

PMMI Electronics Song Directory for "THE" HORN & THE Ultimate HORN Ordering Instructions When programming THE Ultimate HORN, you may choose 100 songs, or fewer, with the total length under or equal to 60,700. (Ultimate Horns purchased after January 1, 2002 can have a total length up to 120,000). When programming "THE" HORN, you may choose 64 songs, or fewer, with the total length under or equal to 31,730. To provide us with the correct number of songs and length, simply mark or circle your selections and then add the song lengths found in the left-hand column next to the songs you have chosen. Then compare the total length against the limits shown above. Send your list of songs along with the horn module box to us at the address at the bottom of this page. The special-program or re-programming charge is $75.00 (plus $6.00 S&H within continental USA). Please call or write us if you have any questions. Songs lists can be sorted by category or by alphabet. Please indicate your preference below. In addition, you may select one song to be your first song (song number 00). _________ Sort by Alphabet Optional First Song Choice _________ Sort by Category ____________________________________ Thank You ! Length Song Name Length Song Name Patriotic / March Patriotic / March 386 AIR FORCE SONG (L) 64 CAISSON'S SONG (S) 82 AIR FORCE SONG (S) 830 EL CAPITAN (L) 172 AMERICA (L) 434 EL CAPITAN (S) 70 AMERICA (S) 1952 ENTRY OF THE GLADIATORS (L) 260 AMERICA THE BEAUTIFUL 456 ENTRY OF THE GLADIATORS (S) 908 AMERICAN PATROL 132 FANFARE 254 ANCHORS AWAY -

Nevada's 2020 State Climate Strategy

NEVADA’S 2020 STATE CLIMATE STRATEGY BUILDS A FOUNDATION FOR FUTURE CLIMATE ACTION “Home means Nevada,”and climate change has hit home. By acting on climate, the state can move toward addressing Nevadans’ concerns and build a better future with cleaner air, better health, an equitable society, economic stability, renewable energy, and a cleaner environment for everyone. Check out our website: www.climateaction.nv.gov CLIMATE ACTION The overarching goals of the Nevada is committed to reducing GHG emissions, which 2020 State Climate Strategy are to: contribute directly to climate change. With the passage of SB 254 in 2019, Nevada adopted aggressive GHG emissions-reduction targets: 28% by 2025, 45% by 2030, and net-zero (near-zero) 1. Provide a framework for reducing by 2050. Nevada’s greenhouse gas (GHG) Under Gov. Sisolak’s executive order on climate change, state emissions across all economic sectors, agencies were directed to develop Nevada’s first-everState 2. Lay the groundwork for climate adaptation Climate Strategy. The 2020 State Climate Strategy informs policymaking on how Nevada will achieve the ambitious targets and resilience, and established by SB 254 and provides an integrated framework for 3. Establish a structure for continued, evaluating climate policies that make sense for Nevada. ongoing climate action across the state. The State Climate Strategy was developed using the best available science, combined with robust input from thousands of Nevadans. CLIMATE JUSTICE Across the United States and in Nevada, low-income communities, people of color, and Indigenous populations have disproportion- ately borne the burden of climate change impacts. As temperatures continue to rise and climate-related challenges expand and intensify, particular attention must be paid to these vulnerable populations. -

The Importance of Music in the Elementary Curriculum: How It Can Be Integrated to Meet Content Standards

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2001 The importance of music in the elementary curriculum: How it can be integrated to meet content standards Lovina-Marie Sawyer Bundy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the Education Commons, and the Music Pedagogy Commons Recommended Citation Bundy, Lovina-Marie Sawyer, "The importance of music in the elementary curriculum: How it can be integrated to meet content standards" (2001). Theses Digitization Project. 1745. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/1745 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPORTANCE OF MUSIC IN THE ELEMENTARY CURRICULUM: HOW IT CAN BE INTEGRATED TO MEET CONTENT STANDARDS A Projact Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Education by Lovina-Marie Sawyer Bundy September 2001 THE IMPORTANCE OF MUSIC IN THE ELEMENTARY CURRICULUM: HOW IT CAN BE INTEGRATED TO MEET CONTENT STANDARDS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by ■ ■ Lovina-Marie Sawyer Bundy September 2001 Apiproved by: Dr.. Mary Vo/Skillings,. First Reader Date Dr ."lZutT Young,, Sepond Reader ., ■ ■ ■ ■ ABSTRACT Improving the quality of teaching and learning' are primary concerns of educators, as they continue to search for better ways of engaging students in the .