'We Are a Family'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement for the Public Record

The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement For the Public Record Edited by Chris Berry, Lu Xinyu, and Lisa Rofel Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2010 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8028-51-1 (Hardback) ISBN 978-988-8028-52-8 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 Printed and bound by CTPS Digiprints Limited in Hong Kong, China Table of Contents List of Illustrations vii List of Contributors xi Part I: Historical Overview 1 1. Introduction 3 Chris Berry and Lisa Rofel 2. Rethinking China’s New Documentary Movement: 15 Engagement with the Social Lu Xinyu, translated by Tan Jia and Lisa Rofel, edited by Lisa Rofel and Chris Berry 3. DV: Individual Filmmaking 49 Wu Wenguang, translated by Cathryn Clayton Part II: Documenting Marginalization, or Identities New and Old 55 4. West of the Tracks: History and Class-Consciousness 57 Lu Xinyu, translated by J. X. Zhang 5. Coming out of The Box, Marching as Dykes 77 Chao Shi-Yan Part III: Publics, Counter-Publics, and Alternative Publics 97 6. Blowup Beijing: The City as a Twilight Zone 99 Paola Voci vi Table of Contents 7. -

“MY LIFE IS TOO DARK to SEE the LIGHT” a Survey of the Living Conditions of Transgender Female Sex Workers in Beijing and Shanghai

“MY LIFE IS TOO DARK TO SEE THE LIGHT” A Survey of the Living Conditions of Transgender Female Sex Workers in Beijing and Shanghai C Based on research in Beijing and Shanghai, China this report focuses on the daily life, working conditions, access to services, and legal frameworks for transgender female sex workers in China. Transgender female sex workers face a broad array of discrimination in social and policy frameworks, preventing this highly marginalized group’s access to a wide spectrum of services and legal protections. They experience amplifed stigma due to both their gender identity and their profession. Isolated and often humiliated when seeking public services, particularly in health care settings, has also led many to self-medicate and engage in dangerous transitioning practices, including on self-administered hormone use. In China, transgender people do not necessarily face outright legal penalties, but the absence of non- discrimination laws and lack of enforcement of overarching policies on non-discriminatory access to healthcare and HIV related services, means they are left without efective protection. As sex work is illegal in China, transgender sex workers are further oppressed by the police and, due to social and other factors, engage in high risk activities that put them at increased risk of HIV and STD infection. The research for this report illuminates that the community of female presenting sex workers is very complex and includes men who have sex with men, transgender individuals, and transsexuals. Their vulnerabilities to HIV and their varied health needs need to be carefully assessed, strategically targeted, and addressed. As China is in the process of drafting a new HIV/AIDS action plan for 2016-2020, now is a good opportunity to develop a specifc strategy on HIV prevention and care for the transgender community. -

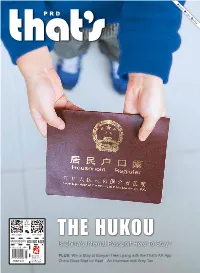

THE HUKOU Advertising Hotline Is China's Internal Passport Here to Stay?

Follow Us on WeChat Now that's guangzhou that's shenzhen China Intercontinental Press THE HUKOU Advertising Hotline Is China's Internal Passport Here To Stay? 城市漫步珠三角 PLUS: 英文版 3 月份 Win a Stay at Banyan Tree Lijiang with the That's AR App 国内统一刊号: MARCH 2017 CN 11-5234/GO China Goes Mad for Beef An Interview with Amy Tan that’s PRD 《城市漫步》珠江三角洲 英文月刊 主管单位 : 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 : 五洲传播出版社 地址 : 北京西城月坛北街 26 号恒华国际商务中心南楼 11 层文化交流中心 11th Floor South Building, Henghua lnternational Business Center, 26 Yuetan North Street, Xicheng District, Beijing http://www.cicc.org.cn 总编辑 Editor in Chief of China Intercontinental Press: 慈爱民 Ci Aimin 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department: 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 编辑 : 梁健 发行 / 市场 : 黄静 李若琳 广告 : 林煜宸 Editor in Chief Jocelyn Richards Shenzhen Editor Sky Thomas Gidge Senior Digital Editor Matthew Bossons Shenzhen Digital Editor Bailey Hu Senior Staff Writer Tristin Zhang Editorial Assistant Ziyi Yuan National Arts Editor Andrew Chin Contributors Dr. Hsing K. Chen, Iain Cocks, Lena Gidwani, Mia Li, Noelle Mateer, Thomas Powell, Betty Richardson, Tongfei Zhang HK FOCUS MEDIA Shanghai (Head Office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 传真 : Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 室 邮政编码 : 510095 Rm 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Luyuan Lu, Guangzhou 510095 电话 : 020-8358 6125 传真 : 020-8357 3859 - 816 Shenzhen 深圳联络处 深圳市福田区彩田路星河世纪大厦 C1-1303 C1-1303, Galaxy Century Building, Caitian Lu, Futian District, Shenzhen 电话 : 0755-8623 3220 传真 : 0755-6406 8538 Beijing 北京联络处 北京市东城区东直门外大街 48 号东方银座 C 座 G9 室 邮政编码 : 100027 9G, Block C, Ginza Mall, No. -

Introduction 1 Mapping Independent Chinese Documentary

Notes Introduction 1. I recognize that this term is conceptually ambiguous, occupying a somewhat vexed position in the history of documentary due to its association with cinéma vérité. Brian Winston (2007, p. 298) has pointed out that initially cinéma vérité referred not to observational documentary – or cinéma direct in French, the ‘fly on the wall’ format in which the director scrupulously erases his or her presence from the cinematic image – but to the particular form of French filmmaking pioneered by Jean Rouch, in which the docu- mentary director consistently inserts him or herself into the frame. However, the anglophone documentary tradition has, over time, tended to confuse the terms, attributing the central principle of cinéma direct to cinéma vérité. In consequence, the latter term is not applied with particular consistency to any single group of films, further dividing scholars over what distinguishes the two approaches. It is for this reason that Bill Nichols (1991, p. 38) has advocated doing away with the term altogether, and replacing it with the concepts of ‘observational’ and ‘interactive’ filmmaking. The situation is com- plicated still further in China, where different kinds of film practice have their own history and vocabulary, sometimes distinct from, sometimes inex- tricably bound up with, those we are more familiar with in Europe and the Americas. Nevertheless, the term vérité has acquired a less specialist currency associated precisely with the type of realism displayed in these films, a point often acknowledged by foreign critics of contemporary Chinese documentary. For this reason, I shall be using it as a general (non-Chinese) shorthand for the aesthetic that is the focus of this book. -

Queer Representations in Chinese-Language Film and the Cultural Landscape

ASIAN VISUAL CULTURES Chao and Landscape the Cultural Film Chinese-language in Representations Queer Shi-Yan Chao Queer Representations in Chinese-language Film and the Cultural Landscape Queer Representations in Chinese-language Film and the Cultural Landscape Asian Visual Cultures This series focuses on visual cultures that are produced, distributed and consumed in Asia and by Asian communities worldwide. Visual cultures have been implicated in creative policies of the state and in global cultural networks (such as the art world, film festivals and the Internet), particularly since the emergence of digital technologies. Asia is home to some of the major film, television and video industries in the world, while Asian contemporary artists are selling their works for record prices at the international art markets. Visual communication and innovation are also thriving in transnational networks and communities at the grass-roots level. Asian Visual Cultures seeks to explore how the texts and contexts of Asian visual cultures shape, express and negotiate new forms of creativity, subjectivity and cultural politics. It specifically aims to probe into the political, commercial and digital contexts in which visual cultures emerge and circulate, and to trace the potential of these cultures for political or social critique. It welcomes scholarly monographs and edited volumes in English by both established and early-career researchers. Series Editors Jeroen de Kloet, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edwin Jurriëns, The University of Melbourne, -

Mail Attachment

Media Contact: Cari Hatcher 612-625-6003 (W) 763-442-1756 (C) [email protected] northrop.umn.edu Press photos at: http://www.northrop.umn.edu/press/event-photos Northrop Concerts and Lectures at the University of Minnesota Announces 2011-12 Northrop Dance Season NORTHROP MOVES to Downtown Minneapolis Minneapolis, MN (April 27, 2011) – Northrop Concerts and Lectures at the University of Minnesota announces it 2011-12 Northrop Dance Season, featuring six of the world’s best ballet and modern dance companies, a trademark of the Northrop experience. The upcoming season reflects the rich tradition of Northrop with premier presentations of seminal artists, provocative productions, inspired choreography, and sensational dancers. During the construction period (Feb 2011-Sept 2013) of the revitalization of Northrop Auditorium, Northrop will move its world-class dance programming to downtown Minneapolis in the highly visible Historic Theatre District on Hennepin Avenue. The first full NORTHROP MOVES season represents the best companies from the United States, China, France, Canada, and the UK. Featuring stunning, important works from choreographers like Sir Kenneth MacMillan, Alvin Ailey, and Jorma Elo, the season also introduces Minnesota audiences to new mavericks like Angelin Preljocaj, Jin Xing, Christopher Wheeldon, and Robert Battle. For more information on the Northrop Revitalization, visit http://northrop.umn.edu/about/northrop-revitalization Highlights of the 2011-12 Northrop Dance Season include: . The MN debut of Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s epic masterworK, Song of the Earth set to music by Mahler performed by Scottish Ballet, Scotland’s leading classical ballet company. Two yet-to-be-named Jorma Elo works – both to be premiered this summer by the Edinburgh Festival in Scotland and by Houston Ballet. -

Capitalization of Feminine Beauty on Chinese Social Media Kunming, Li

Tilburg University Capitalization of Feminine Beauty on Chinese Social Media Kunming, Li Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Kunming, L. (2018). Capitalization of Feminine Beauty on Chinese Social Media. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. sep. 2021 Capitalization of Feminine Beauty on Chinese Social Media Capitalization of Feminine Beauty on Chinese Social Media PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op woensdag 7 maart 2018 om 16.00 uur door Kunming Li geboren te Luoyang, Henan, People’s Republic of China Promotores: Prof.