THERE's GOLD in THEM 'THAR HILLS! by MARIELLE LUMANG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge

Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge Business Plan Table of Contents 2 Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites Executive Summary 3 Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge Business Plan • • • • • • • • Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge 4 Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites 5 Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge Business Plan Site and Operations Assessment 6 Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites 7 Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge Business Plan • • • • • • • • 8 Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 9 Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge Business Plan • • • • • • • • 10 Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites 11 Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge Business Plan Amicalola Falls State Park & Lodge 2008 2009 2010 -

Unicoi State Park & Lodge Overview

Unicoi State Park & Lodge Overview Unicoi State Park & Lodge can be found tucked away in the North Georgia mountains, just outside the charming town of Helen, Georgia – a re-creation of a Bavarian Alpine village and the state’s third most- visited city. Boasting 1,029 acres of Georgia wilderness, visitors can enjoy the 53-acre Unicoi Lake, located between mountaintops and trails to Helen and Anna Ruby Falls, and venture out into nature’s playground. Unicoi State Park & Lodge features an array of amenities and unique ways to experience the outdoors. The 100-room mountaintop lodge offers comfortable accommodations, which are being renovated in 2019, and modern conveniences, looking out on scenic forest views. The property’s 29 cabins, 82 wooded campsites and adventure camp are a popular choice for family trips or romantic mountain getaways. For those looking to completely immerse themselves in the wilderness, Unicoi State Park is home to a primitive camping platform cleverly named the ‘Squirrel’s Nest,’ offering a front row seat to mother nature. As part of a joint venture between the property’s management company, Coral Hospitality and the North Georgia Mountains Authority (NGMA), Unicoi State Park and Lodge is part of the Adventure Lodge Program, making the property a place to both stay and play. Awarded the 2017 Paul Nelson Award for Outdoor Recreation and Preservation for the innovative Adventure Lodge Program, the property is the perfect destination for thrill seekers of all ages and team-building outings. With a variety of activities including archery, air rifle, zip lining and hiking, guests are sure to get their adrenaline pumping. -

Ground-Water Conditions and Studies in Georgia, 2004–2005 Scientific Investigations Report 2007-5017 David C

Ground-Water Conditions and Studies in Georgia, 2004 – 2005 Scientific Investigations Report 2007-5017 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover photograph: Big Spring, Gordon County, Georgia Photograph by Alan M. Cressler, U.S. Geological Survey, 2006 Ground-Water Conditions and Studies in Georgia, 2004 – 2005 By David C. Leeth, Michael F. Peck, and Jaime A. Painter Scientific Investigations Report 2007-5017 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Leeth, D.C., Peck, M.F., and Painter, J.A., 2007, Ground-Water Conditions and Studies in Georgia, 2004– 2005: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2007-5017, 299 p., publication available at http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2007/5017/. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 -

Self-Guided Driving Tours: Regional Towns & Outdoor Recreation Areas

13 10 MILES N 14 # ©2020 TreasureMaps®.com All rights reserved Chattanooga Self-Guided Driving Tours: NORTH CAROLINA NORTH 2 70 miles Nantahala 68 GEORGIA Gorge Regional Towns & Outdoor MAP AREA 74 40 miles Asheville co Recreation Areas O ee 110 miles R i ve r Murphy Ocoee 12 Whitewater 64 1 Aska Adventure Area Center 2 Suches 64 3 Blairsville 69 175 Copperhill Blood Mountain-Walesi-Yi TENNESSEE NORTH CAROLINA 4 GEORGIA Interpretive Center GEORGIA McCaysville GEORGIA 75 5 Richard Russell Scenic Epworth spur T 76 11 o 60 Hiwassee Highway c 5 c 129 8 Cohutta o a 6 Brasstown Bald Wilderness BR Scenic RR 60 Young R 288 iv Harris e 7 Vogel State Park r Mineral Bluff 8 Young Harris & Hiawassee 2 6 Mercier 3 Brasstown 9 Alpine Helen Orchards Bald Morganton Blairsville 10 Dahlonega Lake 515 Blue 17 old 11 Cohutta Wilderness Ridge 76 Blue Ocoee Whitewater Center Ridge 19 12 A s k a 60 13 Cherohala Skyway R oa 180 Benton TrailMacKaye 1 d 7 14 Nantahala River & Gorge Vogel State Park 15 Ellijay Cooper Creek 17 CHATTAHOOCHEE Scenic Area 16 Amicalola Falls Rich Mtn. 75 Fort Mountain State Park Wilderness 17 Unicoi 515 180 4 5 State Toccoa 356 52 River 348 Park Main Welcome Center 19 Helen McCaysville Visitor Center 60 9 Benton MacKaye Trail Suches Ellijay Appalachian Trail 15 Three 2 Forks 75 64 Highway Number NATIONAL Appalachian Trail 129 alt Atlanta 19 75 miles Springer 75 Mountain 52 Cleveland 255 16 Amicalola FOREST Falls State Park 10 Dahlonega 115 52 129 Get the free App! https://www.blueridgemountains.com/ get-the-app/ 14 Nantahala River & Gorge, Follow Highway 19/74 through Self-Guided Driving Tours: Regional 6 Brasstown Bald, Rising 4,784 feet above sea level is # Georgia’s highest point atop Brasstown Bald. -

Teacher Notes for the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Social Studies

Georgia Studies Teacher Notes for the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Social Studies The Teacher Notes were developed to help teachers understand the depth and breadth of the standards. In some cases, information provided in this document goes beyond the scope of the standards and can be used for background and enrichment information. Please remember that the goal of social studies is not to have students memorize laundry lists of facts, but rather to help them understand the world around them so they can analyze issues, solve problems, think critically, and become informed citizens. Children’s Literature: A list of book titles aligned to the 6th-12th Grade Social Studies GSE may be found at the Georgia Council for the Social Studies website: https://www.gcss.net/site/page/view/childrens-literature The glossary is a guide for teachers and not an expectation of terms to be memorized by students. In some cases, information provided in this document goes beyond the scope of the standards and can be used for background and enrichment information. Terms in Red are directly related to the standards. Terms in Black are provided as background and enrichment information. TEACHER NOTES GEORGIA STUDIES Historic Understandings SS8H1 Evaluate the impact of European exploration and settlement on American Indians in Georgia. People inhabited Georgia long before its official “founding” on February 12, 1733. The land that became our state was occupied by several different groups for over 12,000 years. The intent of this standard is for students to recognize the long-standing occupation of the region that became Georgia by American Indians and the ways in which their culture was impacted as the Europeans sought control of the region. -

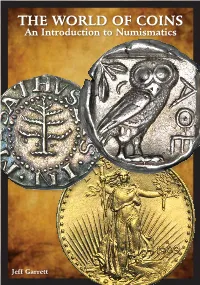

THE WORLD of COINS an Introduction to Numismatics

THE WORLD OF COINS An Introduction to Numismatics Jeff Garrett Table of Contents The World of Coins .................................................... Page 1 The Many Ways to Collect Coins .............................. Page 4 Series Collecting ........................................................ Page 6 Type Collecting .......................................................... Page 8 U.S. Proof Sets and Mint Sets .................................... Page 10 Commemorative Coins .............................................. Page 16 Colonial Coins ........................................................... Page 20 Pioneer Gold Coins .................................................... Page 22 Pattern Coins .............................................................. Page 24 Modern Coins (Including Proofs) .............................. Page 26 Silver Eagles .............................................................. Page 28 Ancient Coins ............................................................. Page 30 World Coins ............................................................... Page 32 Currency ..................................................................... Page 34 Pedigree and Provenance ........................................... Page 40 The Rewards and Risks of Collecting Coins ............. Page 44 The Importance of Authenticity and Grade ............... Page 46 National Numismatic Collection ................................ Page 50 Conclusion ................................................................. Page -

1849, Open Wreath, Small Head

SOUTHERN GOLD DOLLARS 1849-C, Closed Wreath Mintage: 11,634 Graded NGC: 99 total, Mint State 31, Finest MS64 (2) The 1849-C Closed Wreath variety can be considered quite scarce in any grade. High grade examples are usually prooflike in appearance but can be difficult to grade due to convex obverse fields (giving the coin a bulged look), which can be confused with damage. Low grade pieces are the norm, with Mint State coins being very rare. The 1849-C Closed Wreath design is scarce in all grades, but it is the only collectible Charlotte Mint gold dollar for the year that is practical to collect. The finest example seen is an MS64 coin that was discovered by me in 2014, and later sold at auction in 2015 for $49,350. 1849-C, Open Wreath Mintage: Unknown and included as part of the 1849-C, Close Wreath Graded NGC: 2 total, Mint State 0, Finest XF45 (1) This issue must be considered the “king” of all gold dollars and is one of the rarest U.S. gold coins. The Charlotte Mint was the only branch mint to receive the new Close Wreath dies in time to strike the 1849-dated coins. All other branch-mint issues are found with Open Wreath designs only. Probably just a handful of coins were struck in Charlotte with the Open Wreath dies. Waldo Newcomer discovered the variety sometime before 1933. It is estimated that currently five are known to exist, the finest being an MS63, which sold for $493,500 in April, 2015. -

2018 Transline Product Price List Visit for Complete Product Detail

List Creation Date Sunday, May 20, 2018 2018 Transline Product Price List Visit www.translinesupply.com for complete product detail ITEM # Vend # Trade Name UPC / Product MSRP Wholesale Qty 2 Price 2 Qty 3 Price 3 Shipping & Transportation>Tapes & Dispensers 1514 497825 3M - Tartan Box Sealing Tape $4.55 $3.0536 $2.800 72 $2.550 1518 375 3M - Scotch Box Sealing Tape 3M Clear $11.12 $7.2036 $6.600 72 $6.110 1524 371018 3M - Tartan Filament Tape 3/4"x60 yards 8934 Clear $5.00 $3.7548 $3.130 96 $2.800 1526 371579 3M - Tartan Filament Tape 1"x60yards $6.15 $4.6036 $3.990 72 $3.500 1528 474096 3M - Tartan Filament Tape 2"x60 yards $11.65 $9.9024 $9.300 48 $7.800 1540 893 3M 371563 - Scotch Filament Tape 1" x 60 yards $16.75 $12.5036 $12.000 72 $11.730 1542 893-1540 3M - Scotch Filament Tape 2" x 60 yards $37.50 $25.1024 $23.900 48 $22.700 1564 673006: 250 Grad Central - Reinforced Tape $15.50 $10.5010 $9.550 20 $8.750 1582 H-190 3M - Scotch Tape Dispenser $24.00 $14.40 1586 376290 3M - 1" Strapping Tape Dispenser 3M-H-10 $23.50 $14.10 Shipping & Transportation>Envelope Mailers & Box Mailers 2135 240140107 MMF 078541220171 - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Cent Bulk $79.35 $51.503 $47.690 2136 240140508 MMF 078541220584 - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Nickel bulk $79.35 $51.503 $47.690 2137 240141002 MMF 078541221024 - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Dime Bulk $76.30 $51.503 $47.690 2138 240142516 MMF 078541222557 - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Quarter Bulk $79.35 $51.503 $47.690 2139 240141101 MMF - Coin Roll Shipper Box - Dollar Bulk $79.35 $51.503 $47.690 1400 FOS-8FX16F -

New Venue Quite Satisfactory for Club Meetings

The SJ CSRA CC now meets at the South Aiken Presbyterian Church at 1711 Whiskey Road The Stephen James CSRA Coin Club of Aiken P.O. Box 11 Pres. J.J. Engel New Ellenton, SC 29809 Web site: www.sjcsracc.org V .P. Pat James Sec. Jim Mullaney Programs: Pat James ANA Rep.: Glenn Sanders Treas. Chuck Goergen Show Chair: Board members Sgt. in Arms: Jim Sproull Photos: Steve Kuhl Publicity: Pat James Newsletter: Arno Safran E-Mail: [email protected] Auctioneer: Jim Sproull Web site: Susie Nulty (see above.) Volume 20, No. 8 the Stephen James CSRA Coin Club, Founded in 2001 August, 2021 Monthly Newsletter Our next will be on Thursday, August 5 at 6:45 PM at the South Aiken Presbyterian church Gymnasium New Venue quite satisfactory for Club Meetings 2021 Club “Zoom” Meeting Schedule Collecting Liberty Seated half-dollar sub-types Jan. 7 Apr. 1 July 1 Oct. 7 By Arno Safran Feb. 4 May 6 Aug. 5 Nov. 4 Mar. 4 June 3 Sept. 2 Dec. 2 Club now meets in new Location 1839 Reeded Edge Bust half & Lib. Std. no drapery half-dollar From the “old” to the “new”; although, not quite! [Enlarge page to fill monitor screen or 150% to view details.] The South Aiken Presbyterian Church of Aiken Last month, the Stephen James CSRA Coin Club Unlike the Barber series of silver coins which lasted a total of held its first meeting at a new location. just twenty-five years, from 1892 thru 1916, the US silver coins that proceeded them--known as the Liberty Seated type--were struck from Prior to the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic we 1836 to 1891, a time-frame that lasted 56 years. -

A Small Place in Georgia: Yeoman Cultural Persistance Terrence Lee Kersey

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 5-21-2009 A Small Place in Georgia: Yeoman Cultural Persistance Terrence Lee Kersey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Kersey, Terrence Lee, "A Small Place in Georgia: Yeoman Cultural Persistance." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SMALL PLACE IN GEORGIA: YEOMAN CULTURAL PRESISTANCE by TERRENCE LEE KERSEY Under the Direction of Glenn Eskew ABSTRACT In antebellum Upcounty Georgia, the Southern yeomanry developed a society independent of the planter class. Many of the studies of the pre-Civil War Southern yeomanry describe a class that is living within the cracks of a planter-dominated society, using, and subject to those institutions that served the planter class. Yet in Forsyth County, a yeomanry-dominated society created and nurtured institutions that met their class needs, not parasitically using those developed by the planter class for their own needs. INDEX WORDS: Yeomanry, Antebellum, South, Upcountry, Georgia, Slavery, Country store, Methodist, Baptist A SMALL PLACE IN GEORGIA: -

Analysis of Dredge Tailings Pile Patterns: Applications for Historical Archaeological Research

Analysis of Dredge Tailings Pile Patterns: Applications for Historical Archaeological Research AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Sarah Elizabeth Purdy for the degree of Master of Arts in Applied Anthropology presented on June 7, 2007. Title: Analysis of Dredge Tailings Pile Patterns: Applications for Historical Archaeological Research. Abstract approved: ________________________________________________________________________________ Dr. David R. Brauner For centuries humans have been searching for precious metals. The search for gold has greatly changed the landscape of the American West, beginning in the 1850s and continuing today. Various gold rushes around the country created mining colonies in remote areas, thereby connecting the frontier with the rest of America and Europe. This research attempts to expand on the previous industrial archaeology literature, which focuses on historic mining sites and landscape patterns, by concentrating solely on dredge mining. This study analyzes dredge mining activity in the Elk City Township (T. 29 N., R. 8 E.) of North Central Idaho. Dredge mining leaves behind a mark on the landscape in the form of tailings piles, which are uniquely patterned due to different technologies. Through a detailed analysis of the tailings pile patterns, an archaeologist can determine what dredging technology was used, the time period of the operation, and the number of workers employed. In order to understand the technology used, part of this work is dedicated to the various forms of dredges that were used, along with the various dredge mining methods. This research provides a set of guidelines for archaeologists to properly document dredge tailings piles and determine their significance. The major contributions of this thesis are to clarify the historical context for dredge mining in North Central Idaho, to identify visible footprints left by this industrial activity, and to identify both pedestrian survey and remote sensing techniques to locate and differentiate between the various dredging technologies.