Booth, Robert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1600 Early Registration Wednesday 3:00Pm-6:00Pm La Salle a (Exhibit Hall)

1600 Early Registration Wednesday 3:00pm-6:00pm La Salle A (Exhibit Hall) 1800 President's Appreciation Dinner Wednesday 6:30pm-9:00pm Honoring Le Salon Kim Quaile Hill, Texas A&M University 2900 2900 Thursday Registration Thursday 7:00am-5:30pm La Salle A (Registration) 2100 Democratic Theory Thursday Political Theory 8:00am-9:30am Acadian I Chair Simon Stacey, University of Maryland, Baltimore County Participants Distributive Justice and the Modern Welfare State David Ramsey, University of West Florida Reflective Partisanship Joshua Preston Miller, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Democratizing Disability: Grounding Equality in our Shared Vulnerability Amber Knight, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Discussant Simon Stacey, University of Maryland, Baltimore County 2100 Public Opinion: Context Matters Thursday Public Opinion 8:00am-9:30am Acadian II Chair Carole J. Wilson, Southern Methodist University Participants How Political Context Influences the Way Citizens Respond To Political Dissatisfaction? Seonghui Lee, Rice University The Defense Variable: Personal and Contextual Connections to Defense Spending Preferences Melinda Rae Tarsi, University of Massachusetts Amherst Connecting Both Ends of the Chain: Perceptions of American Economic Foreign Policy in the United States and Abroad Daniel Doran Partin, University of Kentucky Political Participation and Policy Feedback in Brazil's Bolsa Familia Program Matthew L Layton, Vanderbilt University Differences Across the Pond: Explaining Differences in Attitudes Toward International Organization in Europe and the United States Nick Clark, Indiana University Nathaniel Birkhead, Indiana University 2100 Nuclear Weapons and International Politics Thursday International Politics: Conflict and Security 8:00am-9:30am Bayou 1 Participants Competing Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy: Pakistan and India Michael Tkacik, Stephen F. -

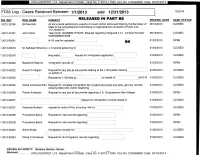

Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 RELEASED IN

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2013-17945 Doc No. C05494608 Date: 04/16/2014 FOIA Log - Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 1/2/2014 tEQ REF REQ_NAME SUBJECT RELEASED IN PART B6 RECEIVE DATE CASE STATUS 2012-26796 Bill Marczak All documents pertaining to exports of crowd control items submitted by the Secretary of 08/14/2013 CLOSED State to the Congressional Committees on Appropriations pursuant to Public Law 112-74042512 2012-31657 John Calvit Task Order: SAQMMA11F0233. Request regarding Vanguard 2.2.1. Contract Number: 08/14/2013 CLOSED GS00Q09BGF0048 L-2013-00001 H-1B visa for requester B6 01/02/2013 OPEN 2013-00078 M. Kathleen Minervino J-1 records pertaining to 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00218 Requestor request for immigration application 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00220 Bashist M Sharma immigration records of 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00222 Robert D Ahlgren Request for any and all documents relating to the 1-130 petition filed by 01/02/2013 CLOSED on behalf of F-2013-00223 Request for 1-130 filed 1.)- on behalf of NVC # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00224 Gloria Contreras Edin Request for complete immigration file including all entries and exits, and any records 01/02/2013 CLOSED showing false USC claims regarding F-2013-00226 Parker Anderson Request for any and all documents regarding U.S. Congressman Sam Steiger. 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00227 request for immigration records receipt # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00237 Kayleyne Brottem request for entire A-File, including 1-94 for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00238 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00239 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00242 Sonia Alcala Immigration records for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00243 Gloria C Cardenas Request for all immigration records regarding 01/02/2013 CLOSED REVIEW AUTHORITY: Barbara Nielsen, Senior Reviewer UNCLASSIFIED U.S. -

Wanted for Murder, Child Abuse, Fraud: Where Are They?

Wanted for murder, child abuse, fraud: Where are they? 2 are implicated of slaughtering their families. One is a dangerous child molester that ran away from custodianship. Another purportedly presented as a religious leader so he could assault ladies. They are amongst the hundreds of fugitives who stay clear of criminal prosecution in the United States each year. Discover much more regarding these fugitives and join John Walsh in his mission to track them down and bring them to justice on "The Quest." After John Walsh's 6-year-old kid, Adam, was abducted and murdered in 1981, he came to be a tireless proponent for sufferers' rights. His groundbreaking program "The united state's A lot of Wanted" is credited with aiding legislation enforcement catch additional than 1,200 fugitives and situating additional than 60 missing kids. Now, Walsh is returning to tv with CNN's "The Hunt" and states he prepares to "saddle back up and capture fugitives." Acquired a suggestion? Call 1-866-THE-HUNT (In Mexico: 0188000990546) or visit this site On May 7, 2013, a 911 dispatcher got a phone call from the residence of Shane and Sandy Miller in Shasta County in northern The golden state. On the many others line, the audios of breathing and sobbing, then loud booms before the line went lifeless. When authorities got to the Millers' residence, they discovered the physical bodies of Sandy Miller and the couple's two children - Shelby, age 8, and Shasta, age 5 - with numerous gunfire wounds. Miller came to the interest of neighborhood legislation enforcement concerning a month previously, when his other half accused him of residential brutality, according to the constable's department. -

81St National Headliner Awards Winners

81st National Headliner Awards winners The 81st National Headliner Award winners were announced this week honoring the best journalism in newspapers, photography, radio, television and online. The awards were founded in 1934 by the Press Club of Atlantic City. The annual contest is one of the oldest and largest in the country that recognizes journalistic merit in the communications industry. Here is a list of this year's winners beginning with the Best of Show in each category: Best of show: Newspapers “Cruel and Usual” Julie K. Brown Miami Herald, Miami, Florida Best of show: Photography “The Ghosts of Ebola” Kieran Kesner Zuma Press, San Clemente, California Best of show: Online First place “The Top of America” TIME Staff, New York, New York Best of show: Radio “Pimlico Preakness Jockeys of Tomorrow” Scott Wykoff WBAL, Baltimore, Maryland Best of show: TV “Deadly Force” Sweta Vohra, Sebastian Walker and the Fault Lines Staff Al Jazeera America, New York, New York DAILY NEWSPAPERS AND NEWS SYNDICATES Spot News in daily newspapers, all sizes First Place “Columbia Mall Shooting” Baltimore Sun Media Group Staff Baltimore Sun, Baltimore, Maryland Second Place “Ferguson Police Officer Kills Michael Brown” St. Louis Post-Dispatch Staff St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis, Missouri Third Place “Ferguson: No Indictment” Associated Press Staff Associated Press, New York, New York Local news beat coverage or continuing story by an individual or team First Place “Cruel and Usual” Julie K. Brown Miami Herald, Miami, Florida Second Place “George Washington Bridge scandal” Shawn Boburg The Record of North Jersey, Hackensack, New Jersey Third Place “Deaths in Police Custody and Parole System Problems” Gina Barton Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Milwaukee, Wisconsin International news beat coverage or continuing story by an individual or team. -

Community Outreach Publication SOUTHFAYETTE TOWNSHIP

AYETTE TO UTH F WNSH SO IP POLICE DEPARTMENT 2016 1951 In its 65th year, the South Fayette Township Police Department includes Three police officers and a Plymouth squad car comprised the first official a chief, 15 police officers and a secretary. From left, Officer James Jeffrey, South Fayette Township Police Department in 1951. From left, Officer Chief John Phoennik and Sgt. Jeff Sgro stand with a fully equipped Ford Sam Migliorini, Chief Armel Kelly and Officer Blackie Diorio stand in the Explorer. Morgan neighborhood soon after the department was formed. Community Outreach Publication Law Enforcement & Community Working Together South Fayette Township Police Department 515 Millers Run Road, South Fayette PA 15064 www.southfayettepa.com/police Emergency & 24/7 Police Dispatch: 9-1-1 Non-Emergency Police Office, M-F, 8 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.: 412-221-2170 Police Chief Township Manager John R. Phoennik Ryan Eggleston Dear Residents of South Fayette Township: The South Fayette Township Police Department, along with Township Manager Ryan Eggleston and the Township Board of Commissioners, believe strongly in offering community-oriented policing and providing the best possible service to our residents, businesses and visitors. As the Chief of Police, I always look for ways our department can better serve our citizens. We hope this Community Outreach Publication will help fulfill our duties and our mission. This booklet offers information about protecting yourself, your property, and your home or business. You will find facts on identity theft, senior citizen safety, fire prevention and other important topics. And you can familiarize yourself with our police department’s many outreach and safety programs, such as Project Life- saver, Child Bicycle Education, Coffee with the Chief, and our Online Anonymous Crime Tip Line. -

Download The-FBI-Story-2014-Web.Pdf

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation 2014 FBI Director James B. Comey speaks to Cyber Division employees at FBI Headquarters. CAPSTitle 20CAPSTitle14 Subtitle and Upper and Upper and Upper and Upper www.fbi.gov The National Cyber Investigative Joint Task Force is composed of nearly two dozen federal intelligence, military, and law enforcement agencies, along with local law enforcement and international and private industry partners. The task force serves as the government’s central hub for coordinating, integrating, and sharing information related to cyber threat investigations. 2014 The FBI Story I A Message from FBI Director James B. Comey It has been a busy and challenging year for the FBI and for our partners at home and around the world. Together, we confronted cyber attacks from sophisticated, state-sponsored actors, transnational criminal groups, and everyday hackers. We arrested white-collar criminals and corrupt public officials. We protected our communities from violent gangs and child predators. And we safeguarded Americans from an array of counterterrorism and counterintelligence threats. This latest edition of The FBI Story, our annual collection of news and feature articles from our public website, FBI.gov, chronicles our most successful 2014 investigations and operations. These include the disruption of botnet operators responsible for the theft of more than $100 million worldwide; nearly $9 billion in penalties levied against one of the largest financial institutions in the world for exploiting the American financial system; and a nationwide child exploitation sweep that recovered 168 victims of trafficking. This edition of The FBI Story also highlights some of our unique capabilities. -

2008 Commencement Program Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Commencement Programs College Publications 5-17-2008 2008 Commencement Program Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/commencement Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "2008 Commencement Program" (2008). Commencement Programs, College Publications, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. Commencement of the Graduates of Undergraduate and Graduate Programs In Arts Entertainment & Media Management, ASL-English 00 0 Interpretation, Eng1ish (Poetry), Fiction Writing, Interactive 0 Arts & Media, Journalism, and Television N Saturday, May 17, 2008, 1:30 p.m. u.. 0 PRESHOW (/) The 2008 Commencement preshow features performances by Columbia College Chicago's (/) student ensembles: <!'. _J The Columbia College Chicago Vocal Jazz Ensemble (Mimi Rohlfing, Director) u The Columbia College Jazz Ensemble (Scott Hall. Director) 00 w The Commencement Choir (Mimi Rohlfing, Director) 0 I The R & B Ensemble (Charles Webb. Director) 0 I- (',I LL Joe Cerqua, Producer/Director 0 Steve Hadley, Associate Producer t- J. Richard Dunscomb, Music Department Chair z I- LU z PROCESSIONAL LU March of the Co/umbians ~ 2 By Scott Hall w w <..) Walk This Way 0 By Joe Perry and Steven Tyler z z w w The Star Spangled Banner By Francis Scott Key 2 2 Arranged by Joe Cerqua 2 2 0 0 0 0 1 Lift Every Voice Music by J. -

Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: the Art and Science of the Human Head

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 10-3-2018 Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: The Art and Science of the Human Head Kourtnei F. Rodriguez [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Rodriguez, Kourtnei F., "Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: The Art and Science of the Human Head" (2018). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rodriguez - i ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Health Sciences & Technology In Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS In Medical Illustration Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: The Art and Science of the Human Head by Kourtnei F. Rodriguez October 3, 2018 Rodriguez - ii Forensic Art in Law Enforcement: The Art and Science of the Human Head Kourtnei F. Rodriguez Chief Advisor: Professor James Perkins Signature: __________________________________ Date: ____________________ Associate Advisor: Professor Glen Hintz Signature: __________________________________ Date: ____________________ Content Expert: Special Agent Walter Henson, Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) Signature: __________________________________ Date: ____________________ Vice Dean, College of Health Sciences &Technology: Dr. Richard Doolittle Signature: __________________________________ Date: ____________________ Rodriguez - iii Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Lt. Kevin Wiley from the Oakland Police Department for providing me with the initial casework for my thesis. I would also like to thank fellow forensic artist Lois Gibson for inviting me to her class, Forensic Art Techniques - Mastering Composite Drawing, at Northwestern University Center for Public Safety. -

The Foreign Service Journal, July 1968

AFSA announces long-term hospital insurance protection for all members under age 69! Now, to meet the increasing expense of hos¬ • Benefits paid directly to you, your hospital pitalization, AFSA offers all members under age or your doctor, as you choose. 69 a low cost hospital indemnity plan that • Even covers you for as long as 30 days keeps paying benefits after most plans stop. for mental disorders. PAYS $15.00 a day for as long as 365 days. • Few exceptions: Policy does not cover: • Benefits are payable in addition to the childbirth, pregnancy or complications; loss Federal Employees Benefits Program or other in¬ caused by war or military service; workmen’s surance you may have. compensation or employer's liability cases; • No waiting period for sickness—covers services provided by or paid for by the US sickness contracted after the policy date. Government; alcoholism. • No waiting period for accidents—covers And, because of the group purchasing power injuries received after the policy date. of your Association, this outstanding plan is • You, spouse and dependent children, who available at low rates that save you money. are eligible, may also be covered under the For further details, complete and mail the plan. coupon below today. UNDERWRITTEN BY AFSA Insurance Program Joseph E. Jones, Administrator 1666 Connecticut Avenue, N.W. Mutual dT\ Washington, D. C. 20009 Please rush me complete details on AFSA’s new Hospital ^maha.vL/ Indemnity Plan. The Company that pays Name age Life Insurance Affiliate: United of Omaha Address MUTUAL OF OMAHA INSURANCE COMPANY State ZIP HOME OFFICE: OMAHA, NEBRASKA City The Foreign Service JOURNAL, is the professional journal of the American Foreign Service and is published monthly by the Foreign Service Association, a non-profit private organization. -

FOIA Logs for Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) for 1999-2004

Description of document: FOIA CASE LOGS for: The Central Intelligence Agency, Washington DC for 1999 - 2004 Posted date: 10-December-2007 Title of Document 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002 Case Log, Unclassified - 2003 Case Log, Unclassified - 1 Jan 04 - l2 Nov 04 Case Log Date/date range of document: 05-January-1999 – 10-November-2004 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, D.C. 20505 Notes: Some Subject of Request fields truncated The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file Unclassified l Jan 04 - l2 Nov 04 Case Loq Creation Date Case Number Case Subject 6-Jan-04 F-2004-00573 JAMES M. PERRY (DECEASED HUSBAND) 6-Jan-04 F-2004-00583 CIA'S SECRET MANUAL ON COERCIVE QUESTIONING DATED 1963. INDEx/DESCRIPTION OF MAJOR INFORMATION SYSTEMS USED BY CIA; GUIDANCE FOR 6-Jan-04 F-2004-00585 OBTAINING TYPES AND CATEGORIES OF PUBLIC INFORMATION FROM CIA; FEE SCHEDULE; DETERMINATION OF WHETHER A RECORD CAN BE RELEASED OR NOT. -

Midwest Political Science Association 73Rdannual Conference April 16 - April 19, 2015

MPSA Midwest Political Science Association 73rdAnnual Conference April 16 - April 19, 2015 Thursday, April 16 at 9:45 am The Institutional Determinants of Regulatory Innovation: Evidence from Renewables Portfolio Standards 2-1 Economies and Identities in the Politics of Social Srinivas Chidambaram Parinandi, University of Michigan Protection Disc., David Stasavage, New York University Chair, Sara Watson, Ohio State University Audience Discussion The 2014 Scottish Referendum and the Nationalism-Social Policy Nexus Daniel Beland, University of Saskatchewan 4-7 Migration I: Consequences for Political Attitudes and Andre Lecours, University of Ottawa Behavior (Co-sponsored with Economic Development, Give Me Your Tired, Your Poor?: Support for Redistribution see 3-10) and Equality in Europe and the United States Chair, Rollin F. Tusalem, Arkansas State University Marc Hooghe, University of Leuven Another Resource Curse?: The Impact of Remittances on The Electoral Risk of Political Decisions Political Participation Jona Linde, Vrije University Amsterdam Kim Yi Dionne, Smith College Barbara Vis, Vrije University, Amsterdam Gabriella Montinola, University of California, Davis Explaining Local Citizens’ Responses to Public Service Kris L. Inman, National Intelligence University Retrenchment A Social Origin of Electoral Support for Authoritarian Kohei Suzuki, Indiana University, Bloomington Regimes: A Case Study of Chinese Immigrants in Hong Kong The Sum of All Fears: State Sponsored Sex, Pro Natalism, and Stan Hok-wui Wong, Chinese University -

Notable Burials in Scottsboro's Cedar Hill Cemetery

Notable Burials in Scottsboro’s Cedar Hill Cemetery The history of Scottsboro can be seen and felt by walking through the headstones of Cedar Hill Cemetery. The distinguished politicians, the doctors and lawyers, the editors, the educators, and the larger-than-life characters all rest here together. Charlotte Scott Skelton, daughter of Scottsboro founder Robert T. Scott, Sr., gave the land for Cedar Hill Cemetery about 1876, but as The Scottsboro Citizen noted on May 21, 1908, the city cemetery had not been named. Mrs. Evie Robinson suggested Cedar Hill, and The Citizen concurred, noting “The suggestion made by this excellent lady is a good one.” There are three Cedar Hill cemeteries in Alabama. 1. Unknown White Male 6. Bob Jones 11. Mary Hunter 2. James K. P. Martin 7. Babs Deal 12. Nat Hamlin Snodgrass 3. Lucille Benson 8. Milo Moody 13. James Armstrong 4. Matt Wann 9. Henry Clay Bradford 14. The Bynums 5. Jessie W. Floyd 10. Col. John Snodgrass 15. Frazier Cemetery 1. Unknown White Male: In the late evening of October 18, 1981, an unidentified man was killed in a hit-and-run incident in Scottsboro. His burial was delayed for five weeks while his picture was circulated nationally and his body was viewed by numerous people searching for lost family members. Thirty-three years after he was buried in Cedar Hill, the FBI placed an alleged murderer, William Bradford Bishop, on its Ten Most Wanted list. After watching a “cold case” program on television, a Scottsboro Funeral Home employee informed the FBI that there was a strong resemblance between the FBI’s wanted man and Scottsboro’s unknown man.