An Investigation Into the 2017 Houston Astros

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Astros' Sign-Stealing Scandal

The Astros’ Sign-Stealing Scandal Major League Baseball (MLB) fosters an extremely competitive environment. Tens of millions of dollars in salary (and endorsements) can hang in the balance, depending on whether a player performs well or poorly. Likewise, hundreds of millions of dollars of value are at stake for the owners as teams vie for World Series glory. Plus, fans, players and owners just want their team to win. And everyone hates to lose! It is no surprise, then, that the history of big-time baseball is dotted with cheating scandals ranging from the Black Sox scandal of 1919 (“Say it ain’t so, Joe!”), to Gaylord Perry’s spitter, to the corked bats of Albert Belle and Sammy Sosa, to the widespread use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) in the 1990s and early 2000s. Now, the Houston Astros have joined this inglorious list. Catchers signal to pitchers which type of pitch to throw, typically by holding down a certain number of fingers on their non-gloved hand between their legs as they crouch behind the plate. It is typically not as simple as just one finger for a fastball and two for a curve, but not a lot more complicated than that. In September 2016, an Astros intern named Derek Vigoa gave a PowerPoint presentation to general manager Jeff Luhnow that featured an Excel-based application that was programmed with an algorithm. The algorithm was designed to (and could) decode the pitching signs that opposing teams’ catchers flashed to their pitchers. The Astros called it “Codebreaker.” One Astros employee referred to the sign- stealing system that evolved as the “dark arts.”1 MLB rules allowed a runner standing on second base to steal signs and relay them to the batter, but the MLB rules strictly forbade using electronic means to decipher signs. -

Group: Leader Search Is Crucial Legislators Say District Superintendent Will Have Long-Term Effect by BRUCE MILLS [email protected]

IN THE CLARENDON SUN: Kindergarten students have a blast gardening A10 Happy USA TODAY: Database gaps leave nation SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894 open to more FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2017 75 CENTS gun violence C1 A perfect tribute Group: Leader search is crucial Legislators say district superintendent will have long-term effect BY BRUCE MILLS [email protected] Because of current rapid technological innovation and continual changes in workforce requirements, members of the Sumter County Legislative Delegation say they think Sumter School District’s up- coming superintendent search represents a “monu- mental” decision for the community. McELVEEN Delegation members shared their thoughts on Tuesday with Sumter School PHOTOS BY BRUCE MILLS / THE SUMTER ITEM District’s Board of Trustees High Hills Elementary School fourth-grader Ayden Apato, 10, shows off a Christmas card he penned to a veteran. Ayden said during their joint meeting at he enjoyed the school’s Veterans Day program Thursday. the district office on educa- tional issues related to the upcoming legislative session High Hills Elementary School pays tribute to veterans SMITH and followed up with more comments Thursday. State Rep. Murrell Smith, R-Sumter, said BY BRUCE MILLS every agenda item the school board shared [email protected] with the delegation at their meeting this ot only does Sumter SEE LEADER, PAGE A9 County boast the highest veteran percentage of total population of any Ncounty in South Carolina at 15.5 percent, according to the U.S. Cen- sus Bureau, but High Hills Elemen- tary School is also located on Shaw 10 awarded Air Force Base, and the school’s teachers and students held a Veter- ans Day ceremony Thursday to fit that statistic. -

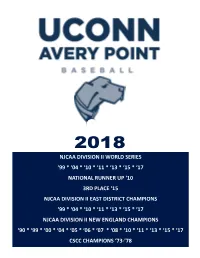

Njcaa Division Ii World Series '99 * '04 * '10 *

NJCAA DIVISION II WORLD SERIES ‘99 * ‘04 * ‘10 * ‘11 * ‘13 * ‘15 * ‘17 NATIONAL RUNNER UP ‘10 3RD PLACE ‘15 NJCAA DIVISION II EAST DISTRICT CHAMPIONS ‘99 * ‘04 * ‘10 * ‘11 * ‘13 * ‘15 * ‘17 NJCAA DIVISION II NEW ENGLAND CHAMPIONS ‘90 * ‘99 * ‘00 * ‘04 * ‘05 * ‘06 * ‘07 * ‘08 * ‘10 * ‘11 * ‘13 * ‘15 * ‘17 CSCC CHAMPIONS ‘73-’78 Letter from the Athletic Director The 2018 Baseball season is quickly approaching the 48th season UCONN AVERY POINT has fielded a Varsity Team, and I reflect on the history of the program as I approach my retirement on August 1st, 2018. The time has sped by to quickly as I clearly remember playing on the 1st Avery Point Championship Team in 1973, winning the Connecticut Small College Conference Championship under Coach George Greer. Defeating Stamford UCONN to clinch the championship with teammates like Pat Kelly, Jeff Kirsch, Herb Gardner, Jerry Stergio, Jay Macko and Mike Wilkinson to name a few. Playing a modest 10 game schedule that fall of 1973 started a streak of 15 consecutive CSCC Championships. When George Greer left to coach Davidson College in 1982, I left UCONN as their baseball graduate assistant to replace Coach Greer as the Athletic Director and Head Baseball Coach and ultimately joining the NJCAA in 1985. This has led to 14 NJCAA New England Championships, 7 East District Championships and 7 World Series appearances. There has been 37 Professional Baseball signee’s, 3 major Leaguers -John McDonald, Rajai Davis and Pete Walker-, 180 players playing at 4 year programs including 56 to UCONN and 18 NJCAA All-Americans. -

2019 California League Record Book & Media Guide

2019_CALeague Record Book Cover copy.pdf 2/26/2019 3:21:27 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 2019 California League Record Book & Media Guide California League Championship Rings Displayed on the Front Cover: Inland Empire 66ers (2013) Lake Elsinore Storm (2011) Lancaster JetHawks (2014) Modesto Nuts (2017) Rancho Cucamonga Quakes (2015) San Jose Giants (2010) Stockton Ports (2008) Visalia Oaks (1978) Record Book compiled and edited by Chris R. Lampe Cover by Leyton Lampe Printed by Pacific Printing (San Jose, California) This book has been produced to share the history and the tradition of the California League with the media, the fans and the teams. While the records belong to the California League and its teams, it is the hope of the league that the publication of this book will enrich the love of the game of baseball for fans everywhere. Bibliography: Baarns, Donny. Goshen & Giddings - 65 Years of Visalia Professional Baseball. Top of the Third Inc., 2011. Baseball America Almanac, 1984-2019, Durham: Baseball America, Inc. Baseball America Directory, 1983-2018, Durham: Baseball America, Inc. Official Baseball Guide, 1942-2006, St. Louis: The Sporting News. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2007. Baseball America, Inc. Total Baseball, 7th Edition, 2001. Total Sports. Weiss, William J. ed., California League Record Book, 2004. Who's Who in Baseball, 1942-2016, Who's Who in Baseball Magazine, Co., Inc. For More Information on the California League: For information on California League records and questions please contact Chris R. Lampe, California League Historian. He can be reached by E-Mail at: [email protected] or on his cell phone at (408) 568-4441 For additional information on the California League, contact Michael Rinehart, Jr. -

2018 Best of Dixie "Hits & Highlights"

The State of South Carolina Dixie Boys and Majors Officials TJ Rostin (State Director Majors) Shannon Loper (State Director Boys) Steve Gavin (State UIC) Ted Jones (Assistant Director) Brian Harlan (Assistant Director) Steve Cook (Legal Advisor) Jim Armour (SC Board Chairman) Boys Majors Matt Watts Rick Meyer Jeff Williamson Dale Percival Tommy Frazier Tommy Frazier Brian Harlan Tony Boiter Kevin Keys Joshua Kinney Laura Boyington Phil Parnell Jim Church Todd Knight Shannon Knight ALABAMA Dixie Boys & Dixie Majors Officials Alabama Dixie Boys Alabama Dixie Majors State Life Member & State Director: State Director: State Director: Hall of Fame 2017: D. Mark Mitchell Keith Robinson Keith Powell Dr. Melvin Allen Assistant State Director: Assistant State Directors: Assistant State Director: LA Boys State UIC: Brian Sharpe Charles Alexander Billy Herrin Don Baudouin Dennis Russell, Carlese Armstrong, District Directors: James Thomas (Retired) Tony Hubbard Jack Stokes Dixie Life Members & State Life Member State Life Members: Charles Glazner District Directors: Tracey Williams Tony Hubbard Dick Primeaux, Dan Touchet District Directors: Dwight Boudreaux, Olin Bertholot, Scott Olsey Ken Mapp —Elected & Appointed— Asst. Kenny Fife, Ricky Frederick, Jonathan Wood Brian Sharpe David Brasher, James C. Thomas, David McKelroy Barry Kephart Secretary/Treasurer: Joel Taylor, Robert Kyle Pam Stewart Steve Sherrill Ralph Thiels Matt Bryant Assistant State Director & Hall of Fame 2015: State Umpire in Chief Assist. State Umpire in Chief Jerry Juneau Dan Capps Ralph Freeman Best wishes from the LA Dixie Boys State Board! COMMISSIONER’S WELCOME Dixie Boys Baseball Inc. has grown from a humble beginning in 1957 to twenty-two thousand plus participants. This publication is intended to provide “hits and highlights” from the 2017 season, as well as offer useful information for the 2018 season. -

Oklahoma City Dodgers Game Information Pacific Coast League Affiliate of the Los Angeles Dodgers Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark | 2 S

Oklahoma City Dodgers Game Information Pacific Coast League Affiliate of the Los Angeles Dodgers Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark | 2 S. Mickey Mantle Drive | Oklahoma City, OK 73104 | Phone: (405) 218-1000 Alex Freedman: (405) 218-2126 | [email protected] | Lisa Johnson: (405) 218-2143 | [email protected] Colorado Springs Sky Sox (18-11) vs. Oklahoma City Dodgers (22-6) Milwaukee Brewers vs. Los Angeles Dodgers Game #29 of 140/Home #16 of 70 (15-0) Pitching Probables: COS-RHP Freddy Peralta (4-1, 4.25) vs. OKC-RHP Tyler Pill (0-0, 6.00) Monday, May 7, 2018 | Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark | Oklahoma City, Okla. | 11:05 a.m. CT Radio: KGHM AM-1340 The Game, 1340thegame.com, iHeartRadio - Alex Freedman Today’s Game: The Oklahoma City Dodgers remain undefeated at Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark as they close out their series against OKC Dodgers Trends Overall Record ............................... 22-6 Colorado Springs with an 11:05 a.m. Field Trip Day game. The Dodgers are 15-0 in Bricktown for their best home start since the ballpark Home Record.................... ............ 15-0 opened in 1998. The Dodgers are the lone team in professional baseball still undefeated at home this season, and their 15-game home winning Road Record.................... ............... 7-6 streak is the team’s second-longest since 1998. Current Streak.................... ............. W4 Current Road Trip............... ................... Last Road Trip..................... ............ 2-2 Last Game: The Dodgers scored two runs in the eighth inning on the way to a 3-2 come-from-behind win against Colorado Springs Sunday Current Homestand .............. ............3-0 Last Homestand............................... 5-0 afternoon. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2018 Remarks Honoring the 2017

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2018 Remarks Honoring the 2017 World Series Champion Houston Astros March 12, 2018 The President. I hope you enjoyed that walk, Jim. [Laughter] That's quite a walk, right? Owner James R. Crane. It was great. The President. Well, I want to thank you. And I'm thrilled to be here and welcome to the White House the 2017 World Series Champion, the Houston Astros. And the—what a team, because I watched our Yankees, and the Yankees were good, and they were tough. They were about as tough as anybody, but you guys were just a little bit tougher. So congratulations. Congratulations. It was—game 7 of the World Series was one of the greatest baseball games anybody has ever seen. Tremendous for the sport, and it's really a reminder why baseball is our national pastime. Thank you to the Energy Secretary, Rick Perry. And he—we love Rick, right? [Applause] Did I do the right job with Rick? I think we did the right job. Right, John? There's John Cornyn too. You know John, your great Senator. And is that Ted Cruz? That's Ted Cruz right there. We have—well represented. You're well represented today. But I do want to thank Senator Cornyn, Senator Cruz, Representative Kevin Brady. Where's Kevin? Where is Kevin? Kevin, are we going for an additional tax cut, I understand? Huh? [Laughter] He's the king of those tax cuts. Yes, we're going to do a phase two. I'm hearing that. You hear that John and Ted? Phase two. -

Saturday, October 27, 2018

THE 114TH WORLD SERIES LOS ANGELES DODGERS VS. BOstON RED SOX SatURDAY, OCTOBER 27, 2018 WORLD SERIES GAME 4 - PREGAME NOTES DODGER StaDIUM, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 2018 WORLD SERIES RESULTS GAME (DATE) RESULT WINNING PITCHER LOSING PITCHER SAVE ATTENDANCE Gm. 1 - Tues., Oct. 23rd BOS 8, LAD 4 Barnes Kershaw — 38,454 Gm. 2 - Wed., Oct. 24th BOS 4, LAD 2 Price Ryu Kimbrel 38,644 Gm. 3 - Fri., Oct. 26th LAD 3, BOS 2 Wood Eovaldi — 53,114 2018 WORLD SERIES SCHEDULE GAME DAY/DATE SITE FIRST PITCH (ET/SITE) TV/RADIO 4 Saturday, October 27th Dodger Stadium 8:09 p.m. ET/5:09 p.m. PT FOX/ESPN Radio 5 Sunday, October 28th Dodger Stadium 8:15 p.m. ET/5:15 p.m. PT FOX/ESPN Radio Monday, October 29th OFF DAY 6* Tuesday, October 30th Fenway Park 8:09 p.m. ET FOX/ESPN Radio 7* Wednesday, October 31st Fenway Park 8:10 p.m. ET FOX/ESPN Radio *If Necessary SERIES AT 2-1 DODGERS AT 1-2 This is the 90th time in World Series history that the Fall Classic has stood • This marks the 12th time that the Dodgers have trailed the Fall at 2-1 after three games. It is the fifth consecutive World Series to sit at Classic, 1-2. The Dodgers also trailed the World Series, 1-2, in 2-1, and it is the 15th time in the last 19 Series (beginning 2000) it has 1916, 1941, 1947, 1949, 1953, 1955, 1965, 1974, 1977, 1981 and occurred. 2017. -

106 Million Viewers Watch All Or Part of 2017 World Series on Fox

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contacts: Eddie Motl, FOX Sports Thursday, November 2, 2017 [email protected] Erik Arneson, FOX Sports [email protected] Claudia Martinez, FOX Deportes [email protected] 106 MILLION VIEWERS WATCH ALL OR PART OF 2017 WORLD SERIES ON FOX FOX, FOX Deportes & FOX Sports GO Combine to Deliver More than 29.3 Million Viewers for Game 7 Game 7 on FOX Deportes is Most-Watched, Non-Soccer Sporting Event in Spanish-Language Cable Television History LOS ANGELES – An eye-popping 106 million viewers watched all or part of the World Series on FOX according to Nielsen Media Research. Wednesday’s emotional World Series Game 7 victory by the Houston Astros over the Los Angeles Dodgers averaged more than 29.3 million viewers across FOX (28,229,000), FOX Deportes (778,000) and streaming live on FOX Sports GO (293,918), according to Nielsen and Adobe Analytics. The game peaked at 31,989,000 viewers from 10:30 to 10:45 PM ET. The complete 2017 World Series on FOX, the 20th delivered by the network, averaged 18,909,000 viewers across all seven games (10.7 HH rating), the second-best audience for a World Series since 2009. While it was -19% below last year’s historic Chicago Cubs’ seven-game victory over the Cleveland Indians, which went into extra innings in Game 7 (23,388,000 viewers), it topped 2015 by +29% (14,700,000) and 2014 by +37% (13,825,000). The World Series also was a hit with younger viewers. Among teens, this year’s World Series enjoyed its second-best rating since 2009 (2.4), outperforming every entertainment primetime program on television. -

The Best Interests of Baseball Clause and the Astros' "High Tech" Sign-Stealing Scandal

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 31 Issue 2 Article 3 2021 The Commissioner Goes Too Far: The Best Interests of Baseball Clause And The Astros' "High Tech" Sign-Stealing Scandal Walter T. Champion Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Walter T. Champion, The Commissioner Goes Too Far: The Best Interests of Baseball Clause And The Astros' "High Tech" Sign-Stealing Scandal, 31 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 215 (2021) Available at: https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol31/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAMPION – ARTICLE 31.2 5/18/2021 10:33 PM ARTICLES THE COMMISSIONER GOES TOO FAR: THE BEST INTERESTS OF BASEBALL CLAUSE AND THE ASTROS’ “HIGH TECH” SIGN- STEALING SCANDAL WALTER T. CHAMPION INTRODUCTION The Commissioner of Baseball, Rob Manfred, penalized the Houston Astros for sign-stealing in 2017, allegedly using “high tech” methods in opposition to the rules of Major League Baseball.1 In a scathing nine-page report the Commissioner made sure to indicate that there was absolutely no evidence that Jim Crane, the Astros’ owner, was aware of any misconduct.2 The Commissioner accused Astros employees in the video replay review room of using live game feed from the center field camera to attempt to decode and transmit opposing teams’ sign sequences. These employees would communicate the sign sequence information by text message which was received on the Apple watch of a staff member on the bench. -

View, 1977-1978

EDMUND P. EDMONDS Professor Emeritus of Law Notre Dame Law School, University of Notre Dame P.O. Box 535, Notre Dame, IN 46556-0535 574-631-5922 - [email protected] 53254 Bracken Fern Drive, South Bend, IN 46637 574-217-7070 - [email protected] Revised - April 2020 EDUCATION LEGAL University of Toledo College of Law, Toledo, Ohio JD, June 1978 Research Editor, The University of Toledo Law Review, 1977-1978 GRADUATE University of Maryland College of Library and Information Services, College Park, Maryland MLS, August 1974 COLLEGE University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana BA (History), May 1973 EMPLOYMENT Notre Dame Law School, University of Notre Dame Professor Emeritus of Law January 2017 to date Associate Dean for Library and Information Technology, Director of the Kresge Law Library, and Professor of Law July 2006 - December 2016 University of St. Thomas School of Law Director of the Schoenecker Law Library and Professor of Law January 2001 - June 2006 Loyola University New Orleans School of Law Director of the Law Library, Professor of Law, and Statistics Coordinator for the School of Law August 1997 - December 2000 Director of the Law Library, Professor of Law, and Assistant Dean for Information Resources August 1994 - July 1997 Director of the Law Library and Professor of Law August 1993 - July 1994 Associate Dean for Academic Affairs, Director of the Law Library and Professor of Law August 1992 - July 1993 Law Librarian and Professor of Law August 1988 - July 1992 Edmund P. Edmonds Page 2 EMPLOYMENT Marshall-Wythe School -

Pressure to Bend the Rules: Is It Worth

Pressure To Bend the Rules: Is It Worth It? A recent Global Ethics Survey revealed that 1 in 5 centerfield camera on the hand signal communications employees in the United States say they feel pressure between the catcher and pitcher of the opposing team. in their jobs to compromise organizational standards. This is illegal under MLB rules. An Astros employee was Studies have shown as internal pressure to told to decode the signals to determine the type of ball compromise ethical standards increases, the likelihood the pitcher was going to throw (e.g., fastball, curveball, of actual employee misconduct increases. More etc.). A different Astros player would run to the dugout troubling, is the lack of repercussions that follow to convey the decoded information. Other players employee misconduct. According to the survey, would ensure this information got to the Astros player employees who felt pressured were twice as likely to at bat. After a few months, the scheme was perfected. see their organization reward unethical behavior (38% They eliminated the runner. The bench coach installed vs. 17%). What message does this send? How does this a monitor inside the dugout with a direct feed to the impact the organization as a whole? Should unethical video replay room. The signals could now be seen and conduct be rewarded? A recent issue involving decoded in real time. They developed a “morse code” employee misconduct within a Major League Baseball in order to transmit the signals to the batter without (“MLB”) team might offer some perspective. delay. Players would bang on a trash can hard enough for the sound to be heard by their teammate at bat.