The Making of the Territorial Order: New Borders and the Emergence of Interstate Conflict∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portugal in the Great War: the African Theatre of Operations (1914- 1918)

Portugal in the Great War: the African Theatre of Operations (1914- 1918) Nuno Lemos Pires1 https://academiamilitar.academia.edu/NunoPires At the onset of the Great War, none of the colonial powers were prepared to do battle in Africa. None had stated their intentions to do so and there were no indications that one of them would take the step of attacking its neighbours. The War in Africa has always been considered a secondary theatre of operations by all conflicting nations but, as well shall see, not by the political discourse of the time. This discourse was important, especially in Portugal, but the transition from policy to strategic action was almost the opposite of what was said, as we shall demonstrate in the following chapters. It is both difficult and deeply simple to understand the opposing interests of the different nations in Africa. It is difficult because they are all quite different from one another. It is also deeply simple because some interests have always been clear and self-evident. But we will return to our initial statement. When war broke out in Europe and in the rest of the World, none of the colonial powers were prepared to fight one another. The forces, the policy, the security forces, the traditions, the strategic practices were focused on domestic conflict, that is, on disturbances of the public order, local and regional upheaval and insurgency by groups or movements (Fendall, 2014: 15). Therefore, when the war began, the warning signs of this lack of preparation were immediately visible. Let us elaborate. First, each colonial power had more than one policy. -

International Law and the Self-Determination of South Sudan

FEBRUARY 2012 No. 231 Institute for Security Studies PAPER International law and the self-determination of South Sudan Africa has long observed taboos against the region and the rest of Africa. For clarity, the paper also changing the national boundaries given newly traces the historical trajectory of southern Sudan’s quest independent countries during decolonisation. for self-determination. Importantly, it is shown how South Whether or not the boundaries were optimal, Sudan’s assertion of the right to self-determination fits into African leaders thought that trying to rationalise emerging normative developments in the African Union them risked continent-wide chaos. Ironically, (AU) and how it helps to identify the limits of state-centric there have been few African border conflicts principles of territorial integrity and uti possidetis vis-à-vis since independence, but the number of internal the fundamental right of self-determination. The overall conflicts has been high … The debate over analysis is particularly valuable for making an informed Sudan’s future, therefore, clearly could affect evaluation of similar claims for self-determination in Africa, all of Africa.1 including, most importantly, the long-standing quest of Somaliland for recognition as an independent state, albeit INTRODUCTION in the end many of these issues depend more on politics On 9 July 2011 South Sudan became the newest than just law. independent state in Africa. Given the importance that is accorded to the inviolability of colonial borders in SELF-DETERMINATION UNDER African international relations, as aptly summarised in INTERNATIONAL AND AFRICAN LAW the quote above, the process of the self-determination of South Sudan has raised questions on discourse about The general international law perspective and the practice of self-determination under general To put the discussion in its proper legal context, it is international law and, significantly, African regional law. -

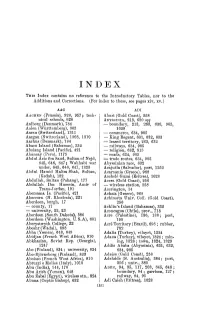

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S. -

Uti Possidetis Juris, and the Borders of Israel

PALESTINE, UTI POSSIDETIS JURIS, AND THE BORDERS OF ISRAEL Abraham Bell* & Eugene Kontorovich** Israel’s borders and territorial scope are a source of seemingly endless debate. Remarkably, despite the intensity of the debates, little attention has been paid to the relevance of the doctrine of uti possidetis juris to resolving legal aspects of the border dispute. Uti possidetis juris is widely acknowledged as the doctrine of customary international law that is central to determining territorial sovereignty in the era of decolonization. The doctrine provides that emerging states presumptively inherit their pre-independence administrative boundaries. Applied to the case of Israel, uti possidetis juris would dictate that Israel inherit the boundaries of the Mandate of Palestine as they existed in May, 1948. The doctrine would thus support Israeli claims to any or all of the currently hotly disputed areas of Jerusalem (including East Jerusalem), the West Bank, and even potentially the Gaza Strip (though not the Golan Heights). TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 634 I. THE DOCTRINE OF UTI POSSIDETIS JURIS ........................................................... 640 A. Development of the Doctrine ..................................................................... 640 B. Applying the Doctrine ................................................................................ 644 II. UTI POSSIDETIS JURIS AND MANDATORY BORDERS ........................................ -

Territorial Integrity and the "Right" to Self-Determination: an Examination of the Conceptual Tools, 33 Brook

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 33 | Issue 2 Article 15 2008 Territorial Integrity and the "Right" to Self- Determination: An Examination of the Conceptual Tools Joshua Castellino Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Joshua Castellino, Territorial Integrity and the "Right" to Self-Determination: An Examination of the Conceptual Tools, 33 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2008). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol33/iss2/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. TERRITORIAL INTEGRITY AND THE "RIGHT" TO SELF-DETERMINATION: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CONCEPTUAL TOOLS Joshua Castellino* INTRODUCTION T he determination and demarcation of fixed territories and the sub- sequent allegiance between those territories and the individuals or groups of individuals that inhabit them is arguably the prime factor that creates room for individuals and groups within international and human rights law.' In this sense, "international society"'2 consists of individuals and groups that ostensibly gain legitimacy and locus standi in interna- tional law by virtue of being part of a sovereign state. For example, al- though it has been argued that notions of democratic governance have become widespread (or even a norm of customary international law),4 this democracy-in order to gain international legitimacy-is assumed to be expressed within the narrow confines of an identifiable territorial unit.5 While this state-centered model has been eroded by international * Professor of Law and Head of Law Department, Middlesex University, London, England. -

Mapping Germany's Colonial Discourse: Fantasy, Reality

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MAPPING GERMANY’S COLONIAL DISCOURSE: FANTASY, REALITY, AND DILEMMA Uche Onyedi Okafor, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013. Dissertation directed by: Professor Elke P. Frederiksen Department of Germanic Studies School of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures This project engages Germany’s colonial discourse from the 18th century to the acquisition of colonies in East Africa during the period of European imperialism. Germany’s colonial discourse started with periphery travels and studies in the 18th century. The writings of German scholars and authors about periphery space and peoples provoked a strong desire to experience the exotic periphery among Germans, particularly the literate bourgeoisie. From a spectatorial and critical positioning vis-à-vis the colonial activities of other Europeans, Germans developed a projected affinity with the oppressed peoples of the periphery. Out of the identificatory positioning with the periphery peoples emerged the fantasy of “model/humane” colonialism (Susanne Zantop). However, studies in Germany’s colonial enterprise reveal a predominance of brutality and inhumanity right from its inception in 1884. The conflictual relationship between the fantasy of “model/humane” colonialism and the reality of brutality and inhumanity, as studies reveal, causes one to wonder what happened along the way. This is the fundamental question this project deals with. Chapter one establishes the validity of the theoretical and methodological approaches used in this project – Cultural Studies, New Historicism and Postcolonialism. Chapter two is a review of secondary literatures on Germany’s colonial enterprise in general, and in Africa in particular. Chapter three focuses on the emergence of the fantasy of “model/humane” colonialism as discussed in Johann Reinhold Forster’s Observations made during a Voyage round the World, 1778, and its demonstration in Joachim Heinrich Campe’s Robinson der Jüngere, 1789. -

Teachers' Notes Empire and Commonwealth: East

TEACHERS’ NOTES EMPIRE AND COMMONWEALTH: EAST AFRICAN CAMPAIGN, 1917 3 August 1914 – November 1918 Background • In 1914 Germany possessed four colonies in sub-SaHaran Africa. THese were Togoland, Kamerun, SoutH-West Africa (now Namibia), and East Africa (now Tanzania). • Capturing Germany’s colonies was an important part of tHe general strategy to starve Germany, and dry up its supplies of fuel and ammunition. By cutting Germany off from all external support, it was speed up tHe process. • Togoland was tHe first German territory captured during tHe war, falling into Allied Hands on 26 August 1914. • British, SoutH African and Portuguese troops captured German SoutH West Africa by July 1915, and British, Nigerian, Indian, French, French Colonial, Belgian and Belgian Colonial forces Had taken Kamerun by March 1916. • WitH most of Germany’s Pacific and Asian colonies also Having fallen to Australian, New Zealand and Japanese troops, the German East Africa colony became tHe last un-captured part of tHe German Colonial Empire TEACHERS’ NOTES from mid-1916 – in fact, it was tHe only part of tHe German Empire to remain undefeated for tHe wHole war. • Lt Col Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck took command of tHe German military forces, determined to tie down as many British resources as possible. His force was mainly comprised of tHe Schutztruppe (Protection Force), an African colonial armed force of local native Askari soldiers commanded by German officers. • THe Askaris were incredibly loyal and very few deserted despite tHe Hardships of tHe campaign. • Completely cut off from Germany and all external supplies, von Lettow conducted an effective guerrilla warfare campaign, living off tHe land, capturing British supplies, and remaining undefeated – a tHree and a Half year game of cat and mouse, wHich He can be considered to Have won. -

German East Africa 72 German East Africa

72 GEORGIA — GERMAN EAST AFRICA No. 309: a, Stylized drawing of ancient Souvenir Sheet European man. b, Skull. 3 2003, Apr. 25 Perf. 12 /4 309 A101 60t Sheet of 2, #a-b 3.75 3.75 Margin of No. 309 has “1700000 YEARS OLD” overprinted in red brown on silver oval that is an overprint over an inscription that reads “17000000 YEARS OLD”. Examples exist without the red brown overprint. Kaiser’s Yacht “Hohenzollern” — A6 In Remembrance of Sept. 11, 2001 Terrorist Attacks — SP12 Self-portrait, by Vincent van Gogh 1900 Typo. Perf. 14 11 A5 2p brown 2.40 1.40 (1853-90) — A108 1 2001, Dec. 31 Litho. Perf. 13x13 /4 12 A5 3p green 2.40 1.60 13 A5 5p carmine 2.75 2.00 3 B13 SP12 30t +10t multi 1.25 1.25 2003, Aug. 25 Perf. 13x12 /4 14 A5 10p ultra 4.50 4.00 326 A108 100t multi 3.50 3.50 Souvenir Sheet 15 A5 15p org & blk, sal 4.50 13.50 B14 SP12 120t +10t multi 4.00 4.00 16 A5 20p lake & blk 6.25 12.50 17 A5 25p pur & blk, sal 6.25 12.50 18 A5 40p lake & blk, rose 7.50 19.00 SEMI-POSTAL STAMPS Engr. GERMAN EAST AFRICA 1 Perf. 14 /2x14 Youth — A102 jər-mən ¯est a-fri-kə 19 A6 1r claret 17.00 47.50 20 A6 2r yellow green 8.25 75.00 1 2003, June 20 Litho. Perf. 14x14 /4 21 A6 3r car & slate 62.50 175.00 Nos. -

Uti Possidetis and the Decolonization of South Asia

WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 130 Frozen frontier: uti possidetis and the decolonization of South Asia Vanshaj Ravi Jain [email protected] October 2019 Refugee Studies Centre Oxford Department of International Development University of Oxford RSC Working Paper Series The Refugee Studies Centre (RSC) Working Paper Series is intended to aid the rapid distribution of work in progress, research findings and special lectures by researchers and associates of the RSC. Papers aim to stimulate discussion among the worldwide community of scholars, policymakers and practitioners. They are distributed free of charge in PDF format via the RSC website. The opinions expressed in the papers are solely those of the author/s who retain the copyright. They should not be attributed to the project funders or the Refugee Studies Centre, the Oxford Department of International Development or the University of Oxford. Comments on individual Working Papers are welcomed, and should be directed to the author/s. Further details can be found on the RSC website (www.rsc.ox.ac.uk). RSC WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 130 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Lines etched in sand: the creation and critique of uti possidetis 2 2.2. The legal status of uti possidetis 5 2.3. The functional critique of uti possidetis 8 3 Frozen frontier: the Radcliffe Line 9 3.1. The duplicity of the Radcliffe Line 9 3.2. Uti possidetis in Punjab 11 3.3. Colonial lines and social upheaval 13 4 Identity and intrastate violence: the construction of communal consciousness in Punjab 15 4.1. Identity in pre-partition Punjab 15 4.2. -

Between a Rock and a Hard Place: the Right to Self-Determination Versus Uti Possidetis in Africa

Between a rock and a hard place: the right to self-determination versus uti possidetis in Africa Freddy D Mnyongani* Abstract The tension between the right of a people to self-determination and the right of a state to its territorial integrity has claimed many lives in Africa. The raison d’être of international law is the regulation of affairs pertinent to its main subjects: states. A difficulty arises when one asserts rights of individuals or peoples within a legal system that is designed for the needs of states. Generally, the international community has not had difficulty with the exercise of the right to self-determination; the problem has always been when its application resulted in secession. In post-colonial Africa, struggles have been waged under the banner of self-determination and these have been thwarted with reference to the right of a state to its territorial integrity. This paper seeks to address this tension as Africa is replete with examples of the suppression of ‘a peoples’’ right to self- determination in favour of the territorial integrity of a state. Introduction International law recognises both the right to self-determination and the right of a state to its territorial integrity, and the tension between the two rights is far from being resolved. Nowhere has this tension played itself out more graphically than on the African continent. Africa has over the last half-a-century lost no less than two million lives in conflicts or wars that have been fought either in pursuit of the right to self-determination, or in defence of colonially inherited boundaries.1 As Neuberger asserts: * BTh (Hons) (St Joseph’s Theological Institute); LLB, LLM (Wits). -

German Colonies

A postal history of the First World War in Africa and its aftermath – German colonies IV Deutsch-Ostafrika / German East Africa (GEA) Ton Dietz ASC Working Paper 119 / 2015 1 Prof. Ton Dietz Director African Studies Centre Leiden [email protected] African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands Telephone +31-71-5273372 Fax +31-71-5273344 E-mail [email protected] Website http://www.ascleiden.nl Facebook www.facebook.nl/ascleiden Twitter www.twitter.com/ascleiden Ton Dietz, 2015 2 A postal history of the First World War in Africa and its aftermath Ton Dietz, African Studies Centre Leiden Version February 2015; [email protected] German Colonies WORK IN PROGRESS, SUGGESTIONS WELCOME IV Deutsch-Ostafrika/German East Africa (GEA) Table of Contents Introduction 2 Vorläufer, 1885-1893 4 Witu and Malakote, 1889 7 Ostafrikanische Seeenpost by Schülke & Mayr, 1892 15 Pre-War stamps, 1893-1914 16 Post offices in German East Africa using their own cancelations, 1893-1914 21 The Great War in East Africa, 1914-1919 38 German occupation of Taveta, 1914-1915 43 Postal services in areas still controlled by Germany 43 Wuga / Mafia 47 British occupation of mainland Tanganyika 51 British Nyasaland Forces and G.E.A. 53 Belgian occupation of Ruanda and Urundi 55 Portuguese occupation of Kionga 62 Former German East Africa after the Great War 68 Tanganyika 68 Ruanda Urundi 72 Quionga and German revisionist vignettes after the War 74 References 75 3 Introduction Wikipedia about German East Africa and its stamps ´German postal services in German East Africa started on October 4, 1890. -

A/63/664–S/2008/823 General Assembly Security Council

United Nations A/63/664–S/2008/823 General Assembly Distr.: General 29 December 2008 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Sixty-third session Sixty-third year Agenda items 13 and 18 Protracted conflicts in the GUAM area and their implications for international peace, security and development The situation in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan Letter dated 26 December 2008 from the Permanent Representative of Azerbaijan to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General On the instructions of my Government, I have the honour to transmit herewith the report on the fundamental norm of the territorial integrity of States and the right to self-determination in the light of Armenia’s revisionist claims (see annex). I should be grateful if you would have the present letter and its annex circulated as a document of the General Assembly, under agenda items 13 and 18 of its sixty-third session, and of the Security Council. (Signed) Agshin Mehdiyev Ambassador Permanent Representative 08-67089 (E) 300109 *0867089* A/63/664 S/2008/823 Annex to the letter dated 26 December 2008 from the Permanent Representative of Azerbaijan to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General Report on the fundamental norm of the territorial integrity of States and the right to self-determination in the light of Armenia’s revisionist claims 1. The present Report provides the view of the Government of the Republic of Azerbaijan on the interrelationship between the legal norm of the territorial integrity of states and the principle of self- determination in international law in the context of the revisionist claims made by the Republic of Armenia (“Armenia”).