Enniskillen Workhouse During the Great Famine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enniskillen Long

E N N I SKI LLEN LON G A GO. A N H I S T O R I C S K E T C H @b2 fi a ris b of I NISH KEENE I N LACU ERNENSI , , N OW CA LLE D E N N I S K I LLE N E E E E I N T H D IOC S O F C L O G H R . B R A D H W . S A W H , A M D U B L I N 1 1 . GEORGE HERBERT, 7 GRAFTON STREET W R L E E S E S T . E LL E N : . N NISKI T IMB , A T BRIDG 1 8 8 7 . D U B L EN G V B B S P R T N T E D B Y P ORT E OUS A N D r 1 8 WT C K LO W STR E E T . C S S A H . £ 6 38 7 8 I N R E M E MB R A NCE M U CH R E S A N D GO O ' LL F I ND HIP D WI , E bis litflz 190a I S AF FE CTI O NATE L Y DE DICAT E D E N N I S K I L L E N E R S , BY O N E W H O L IVE D A M O NG TH E M E A N D T E Y E R S FIV W NTY A , A S A M S E R O F E R R S R INI T TH I PA I H CHU CH. -

Lisnaskea (Updated May 2021)

Branch Closure Impact Assessment Closing branch: Lisnaskea 141 Main Street Lisnaskea BT92 0JE Closure date: 07/07/2021 The branch your account(s) will be administered from: Enniskillen Information correct as at: February 2021 1 What’s in this brochure The world of banking is changing and so are we Page 3 How we made the decision to close this branch What will this mean for our customers? Customers who need more support Access to Banking Standard (updated May 2021) Bank safely – Security information How to contact us Branch information Page 6 Lisnaskea branch facilities Lisnaskea customer profile (updated May 2021) How Lisnaskea customers are banking with us Page 7 Ways for customers to do their everyday banking Page 8 Other Bank of Ireland branches (updated May 2021) Bank of Ireland branches that will remain open Nearest Post Office Other local banks Nearest free-to-use cash machines Broadband available close to this branch Other ways for customers to do their everyday banking Definition of key terms Page 11 Customer and Stakeholder feedback Page 12 Communicating this change to customers Engaging with the local community What we have done to make the change easier 2 The world of banking is changing and so are we Bank of Ireland customers in Northern Ireland have been steadily moving to digital banking over the past 10 years. The pace of this change is increasing. Since 2017, for example, digital banking has increased by 50% while visits to our branches have sharply declined. Increasingly, our customers are using Post Office services with 52% of over-the-counter transactions now made in Post Office branches. -

Sustaining Improvement Inspection (Involving Action Short Of

PRIMARY INSPECTION Brookeborough Primary School, Brookeborough, County Fermanagh Education and Training Inspectorate Controlled, co-educational Report of a Sustaining Improvement Inspection (Involving Action Short of Strike) in March 2017 Sustaining Improvement Inspection of Brookeborough Primary School, County Fermanagh (201-1894) Introduction In the last inspection held in September 2013, Brookeborough Primary School was evaluated overall as very good1. A sustaining improvement inspection (SII) was conducted on 8 March 2017. The purpose of the SII is to evaluate the extent to which the school is capable of demonstrating its capacity to effect improvement through self-evaluation and effective school development planning. Four of the teaching unions which make up the Northern Ireland Teachers’ Council (NITC) have declared industrial action primarily in relation to a pay dispute. This includes non-co-operation with the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI). Prior to the inspection, the school informed the ETI that all of the teachers including the principal would not be co-operating with the inspectors. The ETI has a statutory duty to monitor, inspect and report on the quality of education under Article 102 of the Education and Libraries (Northern Ireland) Order 1986. Therefore, the inspection proceeded and the following evaluations are based on the evidence as made available at the time of the inspection. Focus of the inspection Owing to the school’s participation in industrial action: • the inspection was unable to focus on evaluating the extent to which the school is capable of demonstrating its capacity to effect improvement through self-evaluation and effective school development planning; and • lines of inquiry were not selected from the development plan priorities. -

THE LONDON Gfaz^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237

THE LONDON GfAZ^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237 ; '.' "• Y . ' '-Downing,Street. Charles, Earl of-Leitrim. '-'--•'. ' •' July 5, 1904. jreorge, Earl of Lucan. The KING has been pleased to approve of the Somerset Richard, Earl of Belmore. appointment of Hilgrpye Clement Nicolle, Esq. Tames Francis, Earl of Bandon. (Local Auditor, Hong Kong), to be Treasurer of Henry James, Earl Castle Stewart. the Island of Ceylon. Richard Walter John, Earl of Donoughmore. Valentine Augustus, Earl of Kenmare. • William Henry Edmond de Vere Sheaffe, 'Earl of Limericks : i William Frederick, Earl-of Claricarty. ''" ' Archibald Brabazon'Sparrow/Earl of Gosford. Lawrence, Earl of Rosse. '• -' • . ELECTION <OF A REPRESENTATIVE PEER Sidney James Ellis, Earl of Normanton. FOR IRELAND. - Henry North, -Earl of Sheffield. Francis Charles, Earl of Kilmorey. Crown and Hanaper Office, Windham Thomas, Earl of Dunraven and Mount- '1st July, 1904. Earl. In pursuance of an Act passed in the fortieth William, Earl of Listowel. year of the reign of His Majesty King George William Brabazon Lindesay, Earl of Norbury. the Third, entitled " An Act to regulate the mode Uchtef John Mark, Earl- of Ranfurly. " by which the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Jenico William Joseph, Viscount Gormanston. " the Commons, to serve ia the Parliament of the Henry Edmund, Viscount Mountgarret. " United Kingdom, on the part of Ireland, shall be Victor Albert George, Viscount Grandison. n summoned and returned to the said Parliament," Harold Arthur, Viscount Dillon. I do hereby-give Notice, that Writs bearing teste Aldred Frederick George Beresford, Viscount this day, have issued for electing a Temporal Peer Lumley. of Ireland, to succeed to the vacancy made by the James Alfred, Viscount Charlemont. -

A Revised List of the Executive Assets in County Fermanagh Is Provided and an Update Will Be Provided to the Assembly Library

Conor Murphy MLA Minister of Finance Clare House, 303 Airport Road West Belfast BT3 9ED Mr Seán Lynch MLA Northern Ireland Assembly Parliament Buildings Stormont AQW: 6772/16-21 Mr Seán Lynch MLA has asked: To ask the Minister of Finance for a list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh. ANSWER A revised list of the Executive assets in County Fermanagh is provided and an update will be provided to the Assembly Library. Signed: Conor Murphy MLA Date: 3rd September 2020 AQW 6772/16-21 Revised response DfI Department or Nature of Asset Other Comments Owned/ ALB Address (Building or (eg NIA or area of Name of Asset Leased Land ) land) 10 Coa Road, Moneynoe DfI DVA Test Centre Building Owned Glebe, Enniskillen 62 Lackaghboy Road, DfI Lackaghboy Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen 53 Loughshore Road, DfI Silverhill Depot Building/Land Owned Enniskillen Toneywall, Derrylin Road, DfI Toneywall Land/Depot (Surplus) Building Owned Enniskillen DfI Kesh Depot Manoo Road, Kesh Building/Land Owned 49 Lettermoney Road, DfI Ballinamallard Building Owned Riversdale Enniskillen DfI Brookeborough Depot 1 Killarty Road, Brookeborough Building Owned Area approx 788 DfI Accreted Foreshore of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares Area approx 15,100 DfI Bed and Soil of Lough Erne Land Owned hectares. Foreshore of Lough Erne – that is Area estimated at DfI Land Owned leased to third parties 95 hectares. 53 Lettermoney Road, Net internal Area DfI Rivers Offices and DfI Ballinamallard Owned 1,685m2 Riversdale Stores Fermanagh BT9453 Lettermoney 2NA Road, DfI Rivers -

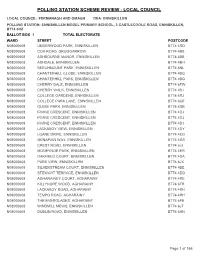

Polling Station Scheme Review - Local Council

POLLING STATION SCHEME REVIEW - LOCAL COUNCIL LOCAL COUNCIL: FERMANAGH AND OMAGH DEA: ENNISKILLEN POLLING STATION: ENNISKILLEN MODEL PRIMARY SCHOOL, 3 CASTLECOOLE ROAD, ENNISKILLEN, BT74 6HZ BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000608UNDERWOOD PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RD N08000608COA ROAD, DRUMGARROW BT74 4BS N08000608ASHBOURNE MANOR, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BB N08000608ASHDALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BH N08000608BEECHMOUNT PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6NL N08000608CHANTERHILL CLOSE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHANTERHILL PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHERRY DALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6FW N08000608CHERRY WALK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BJ N08000608COLLEGE GARDENS, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RJ N08000608COLLEGE PARK LANE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6GF N08000608GLEBE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DB N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608LACKABOY VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DY N08000608LOANE DRIVE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608MENAPIAN WAY, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4GS N08000608CREST ROAD, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JJ N08000608MONEYNOE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4ER N08000608OAKFIELD COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DA N08000608PARK VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JX N08000608SILVERSTREAM COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BE N08000608STEWART TERRACE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608AGHARAINEY COURT, AGHARAINY BT74 4RE N08000608KILLYNURE WOOD, AGHARAINY BT74 6FR N08000608LACKABOY ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608TEMPO ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608THE EVERGLADES, AGHARAINY BT74 6FE N08000608WINDMILL -

GENEALOGY Or THE

GENEALOGY OF TH E F A M I L Y O F ' O L E C , “ OF THE COUNTY OF DEVON, AND OF TH OSE OF ITS B ANC ES W C SE ED IN U FO K MPS E R H HI H TTL S F L , HA HIR , SU EY LIN OL SRIR E A N D IR E A D RR , C N , L N , WIN-C OLE JAMES ED . F T E: N E E M E BAR R KSTE R O H IN R T PL , T o I " Of the Genealo ical Histor of Families Si r R ob ert Atk ns wri es This has its e uli ar g y , y t p c use ; i t stim ulates and excites the brave to im ita te the generous acti ons of their ancestors ; and it shm nes the de auched and re ro a e o h i n the e es of o hers and i n heir own reas s b p b t , b t y t t b t , " — when he nsi er how h hav de enera ed. a e IL Pre a e to The A and n t y co d t ey e g t P g , f c nci ent Pr ese t r . li ndon 1 68. Sta te of Gloucestershi e, 2nd ed , fo o, Lo , 7 L O N DO N PR IN TE D FOR PR IVA TE 'I LATI N C R CU O , BY O USS-E SM 3 S E 6 O U . -

1926 Census County Fermanagh Report

GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1926 COUNTY OF FERMANAGH. Printed and presented pursuant to the provisions of 15 and 16 Geo. V., ch. 21 BELFAST: PUBLISHED BY H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND. To be purchased directly from H. M. Stationery Office at the following addresses: 15 DONEGALL SQUARE WEST, BELFAST: 120 GEORGE ST., EDINBURGH ; YORK ST., MANCHESTER ; 1 ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF ; AD ASTRAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONDON, W.C.2; OR THROUGH ANY BOOKSELLER. 1928 Price 5s. Od. net THE. QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY OF BELFAST. iii. PREFACE. This volume has been prepared in accordance with the prov1s1ons of Section 6 (1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland), 1925. The 1926 Census statistics which it contains were compiled from the returns made as at midnight of the 18-19th April, 1926 : they supersede those in the Preliminary Report published in August, 1926, and may be regarded as final. The Census· publications will consist of:-· 1. SEVEN CouNTY VoLUMES, each similar in design and scope to the present publication. 2. A GENERAL REPORT relating to Northern Ireland as a whole, covering in more detail the. statistics shown in the County Volumes, and containing in addition tables showing (i.) the occupational distribution of persons engaged in each of 51 groups of industries; (ii.) the distribution of the foreign born population by nationality, age, marital condition, and occupation; (iii.) the distribution of families of dependent children under 16 · years of age, by age, sex, marital condition, and occupation of parent; (iv.) the occupational distribution of persons suffering frominfirmities. -

Introduction to the Brookeborough Papers Adobe

INTRODUCTION BROOKEBOROUGH PAPERS November 2007 Brookeborough Papers (D3004 and D998) Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................3 Family history...........................................................................................................4 Plantation Donegal ..................................................................................................5 The Brookes come to Fermanagh ...........................................................................6 The last of the Donegal Brookes..............................................................................7 The Brookes of Colebrooke, c.1685-1761 ...............................................................8 Sir Arthur Brooke, Bt (c.1715-1785).........................................................................9 Major Francis Brooke (c.1720-1800) and his family...............................................10 General Sir Arthur Brooke (1772-1843) .................................................................11 Colonel Francis Brooke (c.1770-1826) ..................................................................12 Major Francis Brooke's other children....................................................................13 Recovery over two generations, 1785-1834 ..........................................................14 The military tradition of the Brookes ......................................................................15 Politics and local government -

Fermanagh Genealogy Centre Leaflet Part 2

List of Civil Parishes in Fermanagh Aghalurcher, Aghavea, Belleek, Boho, Cleenish, Clogher, Clones, Currin, Derrybrusk, Derryvullan, Devenish, Drumkeeran, Drummully, Enniskillen, Galloon, Inishmacsaint, Killesher, Kinawley, Magheracross, Magheraculmoney, Rossory, Templecarn, Tomregan, Trory FERMANAGH There are over 2200 townlands in Fermanagh. genealogy centre Helping you find your Fermanagh roots Baronies of Fermanagh Irvinestown Belleek Enniskillen Lisnaskea Clanawley Clankelly Coole Knockninny Lurg Magheraboy Magherastephana Tirkennedy Fermanagh Genealogy Centre, Enniskillen Castle Enniskillen County Fermanagh BT74 7HL Email: [email protected] Phone: +44 (0) 28 66 323110 Designed & Printed by Ecclesville Printing Services | 028 8284 0048 www.epsni.com Printing Ltd Ecclesville by Designed & Printed SEARCHING FOR YOUR ANCESTORS Preserving Fermanagh’s Volunteers helping you find your genealogical heritage Fermanagh Roots WHO WE ARE AN OPPORTUNITY TO Fermanagh Genealogy Centre is run by BE A VOLUNTEER Volunteers. It was established in 2012 Volunteering for the Genealogy Centre and has operated as a delivery partner is an opportunity to make new friends for Fermanagh and Omagh District and to help others in their search for Council since October 2013 their family history connections to Fermanagh. It is also an opportunity WHAT WE ARE to learn more about how to search for We are a charitable organisation, who your own family history. We provide assist visitors to find their family history regular training for our volunteers, so connections in Fermanagh. Our aim is to that they are familiar with the range create a welcoming place for visitors and of material available. Opportunities exist Frank McHugh with visitors to the Fermanagh Genealogy volunteers for people to volunteer in the Centre on a Genealogy Centre, Dorothy McDonald volunteers, irrespective of religious, and her husband, Malcolm. -

Introduction Porter Papers

INTRODUCTION PORTER PAPERS November 2007 Porter Papers (D1390/10, N/19, LR1/178/1) Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................2 Family history...........................................................................................................3 The Belleisle estate .................................................................................................4 The townlands .........................................................................................................5 Fermanagh and Longford ........................................................................................6 Clogher Park............................................................................................................7 The 'Regency' period ...............................................................................................8 Railways and libel actions........................................................................................9 A scandalous affair ................................................................................................10 The Lisbellaw Gazette ...........................................................................................11 Other ventures .......................................................................................................12 Political affairs........................................................................................................13 Porter-Porter ..........................................................................................................14 -

Enniskillen, Nov 6Th 1834 Dear Sir. I Send You the Name Books Of

Enniskillen, Nov 6th 1834 River (ABHAINN NA SAILISE) he slipped on its slippery banks and the books fell off his horns and it was sometime before he could fix them up again. This Dear Sir. was affected by the genius or sheaver (shaver) who presided over the Sillees, I send you the name books of Templecarn, Devenish, Enniskillen, ' who did all in his power to prevent the establishment of the christian religion in Derryvullan, Boho and Inishmacsaint. I expect that Mr. Sharkey will have the that neighbourhood. As soon as Faber had understood that the demon of the usual watch on me. It is very difficult to adhere to the analogies of Derry and river thus annoyed the good beast, she cursed the river praying that the Sillees Down in the names of this county, because the pronunciation is nearly might be cursed with sterility of fish and fertility in the destruction of human Connaught. The termination reagh, I was obliged to make reevagh in some life, and that it might run against the hill. The curse was pronounced in the instances, and garve, I had to make garrow. The word TAOBH, i.e. side or brae- following Irish words:- face frequently enters into the names here; this we have anglicized Tieve in MI-ADH EISC A'S ADH BAIDHTE Derry, Down & Antrim. I have used the same spelling of it here, but I am afraid it is too violent as every authority makes it Teev. The more northerly AG RITH ANAGHAIDH AN AIRD GO LA BRATHA. pronunciation is tee-oov, the Fermanagh one Teev.