Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expiration and Vacancies Governor July 2021

State of Illinois Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability Expiration and Vacancies Governor July 2021 802 Stratton Office Building Springfield, IL 62706 Phone: 217/782-5320 Fax: 217/782-3515 http://cgfa.ilga.gov JOINT COMMITTEE ON LEGISLATIVE SUPPORT SERVICES House Republican Leader/Chairperson Rep. Jim Durkin Senate Republican Leader Sen. Dan McConchie President of the Senate Sen. Don Harmon Speaker of the House Rep. Emanuel “Chris” Welch COMMISSION ON GOVERNMENT FORECASTING AND ACCOUNTABILITY Co-Chairperson Sen. David Koehler Co-Chairperson Rep. C. D. Davidsmeyer Executive Director Clayton Klenke Deputy Director Laurie Eby Senators Representatives Omar Aquino Amy Elik Darren Bailey Amy Grant Donald P. DeWitte Sonya Harper Elgie Sims Elizabeth Hernandez Dave Syverson Anna Moeller The Commission on Government Forecasting & Accountability is a bipartisan legislative support service agency that is responsible for advising the Illinois General Assembly on economic and fiscal policy issues and for providing objective policy research for legislators and legislative staff. The Commission’s board is comprised of twelve legislators-split evenly between the House and Senate and between Democrats and Republicans. The Commission has three internal units--Revenue, Pensions, and Research, each of which has a staff of analysts and researchers who analyze policy proposals, legislation, state revenues & expenditures, and benefit programs, and who provide research services to members and staff of the General Assembly. The Commission’s Revenue and Pension Units annually publish a number of statutorily mandated reports as well as on-demand reports in regard to Illinois’ financial and economic condition, the annual operating and capital budgets, public employee retirement systems, and other policy issues. -

Preliminary Fall 2019 Enrollments in Illinois Higher Education

Item #I-1 December 10, 2019 PRELIMINARY FALL 2019 ENROLLMENTS IN ILLINOIS HIGHER EDUCATION Submitted for: Information. Summary: This report summarizes preliminary fall-term 2019 headcount and full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollments at degree-granting colleges and universities in Illinois. The report also summarizes enrollments in remedial/developmental courses during the 2018- 2019 academic year. Fall 2019 preliminary headcount enrollments at degree-granting institutions total 720,215 and preliminary FTE enrollments total 541,187. Brisk Rabbinical College did not respond to the survey and therefore was excluded from the report. Action Requested: None 323 Item #I-1 December 10, 2019 PRELIMINARY FALL 2019 ENROLLMENTS IN ILLINOIS HIGHER EDUCATION This report summarizes preliminary fall-term 2019 headcount and full-time-equivalent (FTE) enrollments at colleges and universities in Illinois. It also includes enrollments in remedial/developmental courses for Academic Year 2018-2019. Fall-term enrollments provide a “snapshot” of Illinois higher education enrollments on the 10th day, or census date, of the fall term. It should be noted that two colleges, Brisk Rabbinical College did not respond to the survey and was therefore excluded from the report. Preliminary fall 2018 enrollments by sector Including enrollments at out-of-state institutions authorized to operate in Illinois, fall 2019 preliminary headcount enrollments at degree-granting institutions total 720,215 (see Table 4 for institutional level data). Fall 2019 FTE enrollments total 541,187. -

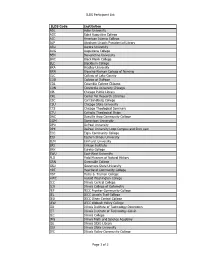

ILDS Participant List ILDS Code Institution ADL Adler University

ILDS Participant List ILDS Code Institution ADL Adler University AGC Saint Augustine College AIC American Islamic College ALP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library ARU Aurora University AUG Augustana College BEN Benedictine University BHC Black Hawk College BLC Blackburn College BRA Bradley University BRN Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing CLC College of Lake County COD College of DuPage COL Columbia College Chicago CON Concordia University Chicago CPL Chicago Public Library CRL Center for Research Libraries CSC Carl Sandburg College CSU Chicago State University CTS Chicago Theological Seminary CTU Catholic Theological Union DAC Danville Area Community College DOM Dominican University DPU DePaul University DPX DePaul University Loop Campus and Rinn Law ECC Elgin Community College EIU Eastern Illinois University ELM Elmhurst University ERI Erikson Institute ERK Eureka College EWU East-West University FLD Field Museum of Natural History GRN Greenville College GSU Governors State University HRT Heartland Community College HST Harry S. Truman College HWC Harold Washington College ICC Illinois Central College ICO Illinois College of Optometry IEF IECC Frontier Community College IEL IECC Lincoln Trail College IEO IECC Olney Central College IEW IECC Wabash Valley College IID Illinois Institute of Technology-Downtown IIT Illinois Institute of Technology-Galvin ILC Illinois College IMS Illinois Math and Science Academy ISL Illinois State Library ISU Illinois State University IVC Illinois Valley Community College Page 1 of 3 ILDS Participant List -

Spring 2016 the Feminist Psychologist

Volume 43 Number 1 Spring 2016 The Feminist Psychologist Newsletter of the Society for the Psychology of Women President’s Column Who Dat!? Sisters, You’ve Been on My Mind: Division 35 Members Visit New Orleans By BraVada Garrett-Akinsanya, PhD, LP his year’s Mid-Winter’s meeting we laughed and cried! We participated BraVada Garrett-Akinsanya, PhD was held in New Orleans, Louisi- in artistic expressions through crafts, BraVada Garrett-Akinsanya, PhD, LP ana right before Mardi Gras! The and drumming. We shared our love Texperience of seeing marching bands, for Social Justice by writing a letter to INSIDE THIS ISSUE floats and colorful beads streaming Mayor Landrieu about increasing healing through the air created a wonderful spaces for children, and we collaborated backdrop to the difficult and important as volunteers and fundraisers with a lo- President’s Column .............................1 work in front of us as group. New Or- cal school, Mos Chukma Institute, for the Research-to-Practice Retreat ...........6 leans is known as a city that embodies children living in the 9th Ward, who were resilience, rhythm, and positive energy most devastated by Hurricane Katrina. Division Officer Candidates .............7 about life. It was there that our Extended We kicked off our visit with an his- Council February Meeting................8 Executive Committee began a journey torical event - a joint Feminist Research- towards the honest reclamation of who to-Practice Task Force retreat with Divi- Second Institute ................................10 we are and we want to be as an APA Divi- sion 42, Independent Practice, co-chaired Walsh Award Presentation .............11 sion. -

Ameren Il 2020 Mid-Year Corporate Political

AMEREN IL 2020 MID-YEAR CORPORATE POLITICAL CONTRIBUTION SUMMARY CommitteeID CommitteeName ContributedBy RcvdDate Amount Address1 City State Zip D2Part 25530 Friends of Mark Batinick Ameren 06/30/2020 $ 1,000.00 PO Box 66892 St. Louis MO 63166 Individual Contribution 17385 Friends of Mattie Hunter Ameren 06/30/2020 $ 2,500.00 P.O. Box 66892 St. Louis MO 63166 Individual Contribution 19155 Citizens for Tom Morrison Ameren 06/30/2020 $ 1,000.00 PO Box 66892 St. Louis MO 63166 Individual Contribution 31972 Citizens for Colonel Craig Wilcox Ameren 06/10/2020 $ 3,000.00 PO Box 66892 St Louis MO 63166 Individual Contribution 35553 Brad Stephens for State RepresentativeAmeren 06/04/2020 $ 1,000.00 P.O. BOX 66892 St. Louis MO 63166 Individual Contribution 34053 Committee to Elect Dan Caulkins Ameren 05/29/2020 $ 1,000.00 200 W Washington Springfield IL 62701 Individual Contribution 31821 Fowler for Senate Ameren 05/09/2020 $ 1,000.00 P.O. Box 66892 St. Louis MO 63166 Individual Contribution 35553 Brad Stephens for State RepresentativeAmeren 04/27/2020 $ 1,000.00 P.O. BOX 66892 St. Louis MO 63166 Individual Contribution 4261 Friends of Mary E Flowers Ameren 04/22/2020 $ 2,000.00 607 E. Adams Street Springfield IL 62739 Individual Contribution 34053 Committee to Elect Dan Caulkins Ameren 03/17/2020 $ 1,000.00 200 W Washington Springfield IL 62701 Individual Contribution 22882 Friends of Rita Mayfield Ameren 03/17/2020 $ 1,000.00 P.O. Box 66892 St. Louis MO 63166 Transfer In 25530 Friends of Mark Batinick Ameren 03/11/2020 $ 1,000.00 PO Box 66892 St. -

Debt Transparency Initiative (Passed House 70-40-0; Passed Senate 37-16-0) House Bill 3649 (Rep

Debt Transparency Initiative (Passed House 70-40-0; Passed Senate 37-16-0) House Bill 3649 (Rep. Fred Crespo - Stephanie A. Kifowit - Marcus C. Evans, Jr. - Brandon W. Phelps, Silvana Tabares, Martin J. Moylan, Robert Martwick, Arthur Turner, Kelly M. Cassidy, Natalie A. Manley, Kathleen Willis, Jehan Gordon-Booth, LaToya Greenwood, Gregory Harris, Frances Ann Hurley, Theresa Mah, Emily McAsey, Christian L. Mitchell, Anna Moeller, Carol Sente, Lawrence Walsh, Jr., Emanuel Chris Welch, William Davis, Justin Slaughter, Michelle Mussman, Carol Ammons, Jerry Costello, II, Katie Stuart, Michael Halpin, Sue Scherer, Litesa E. Wallace and Elizabeth Hernandez) Senate Bill 1652 (Sen. Andy Manar - Pat McGuire - Iris Y. Martinez - Melinda Bush - Don Harmon, Laura M. Murphy, Omar Aquino, Jennifer Bertino-Tarrant, Linda Holmes and Steve Stadelman) Purpose The state’s unprecedented fiscal challenges require a full weighing of outstanding vouchers and the ramifications of the $12 billion-plus unpaid bill backlog. House Bill 3649/Senate Bill 1652 seeks to provide a more accurate accounting of bills being held by each state agency and the late interest penalties the state is accruing. Background: After appropriations are made and services are provided, each state agency sends bills to the Comptroller for payment. However, if vouchers for payment are held at the agency level due to a lack of appropriation or processing delays, these liabilities remain largely hidden from the Comptroller. The state’s Prompt Payment Act, which assigns a 1% per month penalty to bills that are 90 days past due, applies to a currently unknown number of the bills being held by the agencies. -

Education Program

2014 Annual Meeting Program April 6-9, 2014 Westin Columbus – Columbus, Ohio This conference is supported in part by an educational grant from Pfizer. ANNUAL MEETING PLANNING COMMITTEE Jonathan A. Schaffir, MD - Chair Assistant Professor, Ohio State University College of Medicine Department of Ob-Gyn, Columbus, OH COMMITTEE Lisa Christian, PhD Ohio State University, Columbus, OH Teri Pearlstein, MD Women's Medicine Collaborative, a Lifespan partner, Brown Chiara Ghetti, MD University, Providence, RI Washington University St. Louis, MO Valerie Waddell, MD Ohio State University, Columbus, OH Shari Lusskin, MD Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Katherine Wisner, MD New York, NY Northwestern University Chicago, IL Michael O'Hara, PhD University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA NASPOG 2014 EXECUTIVE BOARD PRESIDENT SECRETARY-TREASURER Jonathan A. Schaffir, MD Cynthia Neill Epperson, MD Assistant Professor, Ohio State University College of Medicine Director of Penn Center for Women’s Behavioral Wellness Department of Obstetrics/Gynecology Associate Professor, Psychiatry / Obstetrics/Gynecology Columbus, OH University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA PRESIDENT-ELECT IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT Shari Lusskin, MD Teri Pearlstein, MD Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Obstetrics, Gynecology and Associate Professor, Alpert Medical School of Brown Reproductive Science University Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai Director of Behavioral Medicine, Women’s Medicine New York, NY Collaborative, a Lifespan partner Providence, RI MEMBERS-AT-LARGE Gregg Eichenfeld, PhD Marce Society Representative St. Paul, MN Katherine L. Wisner, MD, MS Sarah Fox, MD Northwestern University Women & Infants Hospital, Chicago, IL Brown University Providence, RI NASPOG National Office Staff Chiara Ghetti, MD Debby Tucker Washington University Executive Director St. -

2017 IHCA Regular Legislative Session Report

2017 IHCA Regular Legislative Session Report 2017 Legislative Session Overview FY17 and FY18 Budget Overview Substantive Legislative Initiatives June 2, 2017 2017 Legislative Session Overview The 2017 regular spring session came to a close with a whimper late Wednesday night. The first year of the 100th General Assembly began with the legislature and Rauner administration returning to Springfield following an acrimonious and bitter 2016 election cycle. The Democrats attempted to make the elections a referendum on the efforts of the Governor and legislative Republicans to tie non-budgetary items such as workers compensation reform, pension relief and property tax relief to the state’s budget. For their part the Republicans did the same, with messaging centered on the use of increasing income tax and protection of union interests against the Democrats. The Democrats seemingly won the day in the 2016 March primary election, defending Republican Senator Sam McCann against a Governor Rauner funded opponent who was slated as punishment for McCann’s stance against Rauner on an AFSCE friendly bill, and defeating incumbent House Democrat Ken Dunkin for his staunch support of the Republican Governor. As well, they handily defeated a Rauner funded primary opponent of Speaker Madigan (placing a primary opponent against a sitting legislative leader is all but verboten in Springfield, making this move something of a shock to the Springfield political establishment). These victories, however, weren’t quite the sign of things to come that some expected in the November general election. In the race for Illinois’ junior Senate seat, Democrat Tammy Duckworth easily surpassed incumbent Republican Senator Mark Kirk. -

Chicago: North Park Garage Overview North Park Garage

Chicago: North Park Garage Overview North Park Garage Bus routes operating out of the North Park Garage run primarily throughout the Loop/CBD and Near Northside areas, into the city’s Northeast Side as well as Evanston and Skokie. Buses from this garage provide access to multiple rail lines in the CTA system. 2 North Park Garage North Park bus routes are some busiest in the CTA system. North Park buses travel through some of Chicago’s most upscale neighborhoods. ● 280+ total buses ● 22 routes Available Media Interior Cards Fullbacks Brand Buses Fullwraps Kings Ultra Super Kings Queens Window Clings Tails Headlights Headliners Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. Do not share North Park Garage Commuter Profile Gender Age Female 60.0% 18-24 12.5% Male 40.0% 25-44 49.2% 45-64 28.3% Employment Status 65+ 9.8% Residence Status Full-Time 47.0% White Collar 50.1% Own 28.9% 0 25 50 Management, Business Financial 13.3% Rent 67.8% HHI Professional 23.7% Neither 3.4% Service 14.0% <$25k 23.6% Sales, Office 13.2% Race/Ethnicity $25-$34 11.3% White 65.1% Education Level Attained $35-$49 24.1% African American 22.4% High School 24.8% Hispanic 24.1% $50-$74 14.9% Some College (1-3 years) 21.2% Asian 5.8% >$75k 26.1% College Graduate or more 43.3% Other 6.8% 0 15 30 Source: Scarborough Chicago Routes # Route Name # Route Name 11 Lincoln 135 Clarendon/LaSalle Express 22 Clark 136 Sheridan/LaSalle Express 36 Broadway 146 Inner Drive/Michigan Express 49 Western 147 Outer Drive Express 49B North Western 148 Clarendon/Michigan Express X49 Western Express 151 Sheridan 50 Damen 152 Addison 56 Milwaukee 155 Devon 82 Kimball-Homan 201 Central/Ridge 92 Foster 205 Chicago/Golf 93 California/Dodge 206 Evanston Circulator 96 Lunt Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. -

Resource Guide for Mental Health 2021-2022

2021 -2022 Resource Guide for Mental Health It’s okay not to be okay. www.squarecarehealth.com Table of Contents Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................... Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Postpartum Care: ................................................................................................................................. 2 Links to resources for Fathers & Families experiencing Postpartum Depression: .................................. 7 Fertility Specialists: .............................................................................................................................. 8 Infertility Counseling: ......................................................................................................................... 16 Online Therapy for Moms: ................................................................................................................. 21 Outpatient Psychiatry Services: .......................................................................................................... 25 Outpatient Psychiatry Services that provides Therapy: ...................................................................... 31 Psychotherapy Services ONLY: ........................................................................................................... 48 Resources for LBGT+ -

December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts

December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts PD290© 2019 INCCRRA Cohort Pathways in Illinois: Innovative Models Supporting the Early Childhood Workforce Institutions of higher education in Illinois have long implemented collaborative, innovative strategies to support credential and degree attainment. The Illinois Governor’s Office of Early Childhood Development (GOECD) is invested in supporting flexible, responsive pathways to credentials and degree attainment for early childhood practitioners, as early childhood practitioners equipped with appropriate knowledge and skills are critical to developing and implementing high-quality early childhood experiences for young children and their families. At the same time, the State of Illinois is eager to ensure that pathways developed not only support entry into and progression within the field, but also are inclusive of and responsive to programs’ diverse and experienced staff members who have not yet attained new credentials and/or degrees. The purpose of this paper is to highlight the innovative work of Illinois institutions of higher education in creating cohort pathways that are responsive to the needs of the current and future early childhood workforce. Cohort models are commonly defined as a group of students moving through a program in a cohesive fashion with support provided for the overall healthy functioning of the group. In this paper, the highlighted cohort pathways focus on additional supports provided to cohort model participants (social and practical) as well as innovative model designs. Understanding these unique cohort pathways requires a fundamental understanding of existing credential and degree pathways in Illinois, the current early childhood education (ECE) workforce, present challenges in growing an ECE workforce, and research highlighting 1 innovative components of cohort models. -

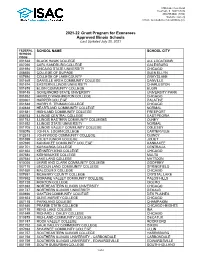

2021-22 Grant Program for Exonerees Approved Illinois Schools Last Updated July 20, 2021

1755 Lake Cook Road Deerfield, IL 60015-5209 800.899.ISAC (4722) Website: isac.org E-mail: [email protected] 2021-22 Grant Program for Exonerees Approved Illinois Schools Last Updated July 20, 2021 FEDERAL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL CITY SCHOOL CODE 001638 BLACK HAWK COLLEGE ALL LOCATIONS 007265 CARL SANDBURG COLLEGE GALESBURG 001694 CHICAGO STATE UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 006656 COLLEGE OF DUPAGE GLEN ELLYN 007694 COLLEGE OF LAKE COUNTY GRAYSLAKE 001669 DANVILLE AREA COMMUNITY COLLEGE DANVILLE 001674 EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON 001675 ELGIN COMMUNITY COLLEGE ELGIN 009145 GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY PARK 001652 HAROLD WASHINGTON COLLEGE CHICAGO 003961 HARPER COLLEGE PALATINE 001648 HARRY S. TRUMAN COLLEGE CHICAGO 030838 HEARTLAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE NORMAL 001681 HIGHLAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE FREEPORT 006753 ILLINOIS CENTRAL COLLEGE EAST PEORIA 001742 ILLINOIS EASTERN COMMUNITY COLLEGES OLNEY 001692 ILLINOIS STATE UNIVERSITY NORMAL 001705 ILLINOIS VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE OGLESBY 008076 JOHN A. LOGAN COLLEGE CARTERVILLE 012813 JOHN WOOD COMMUNITY COLLEGE QUINCY 001699 JOLIET JUNIOR COLLEGE JOLIET 007690 KANKAKEE COMMUNITY COLLEGE KANKAKEE 001701 KASKASKIA COLLEGE CENTRALIA 001654 KENNEDY-KING COLLEGE CHICAGO 007684 KISHWAUKEE COLLEGE MALTA 007644 LAKE LAND COLLEGE MATTOON 010020 LEWIS AND CLARK COMMUNITY COLLEGE GODFREY 007170 LINCOLN LAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE SPRINGFIELD 001650 MALCOLM X COLLEGE CHICAGO 007691 MCHENRY COUNTY COLLEGE CRYSTAL LAKE 007692 MORAINE VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE PALOS HILLS 001728 MORTON COLLEGE CICERO