America's Heartland Remembers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eclectic Guests Highlight Record Dinner Turnout

Page 12 Thursday, February 15, 2018 The Westfield Leader and The Scotch Plains – Fanwood TIMES A WATCHUNG COMMUNICATIONS, INC. PUBLICATION Area stores that carry The Westfield Leader and The Scotch Plains – Fanwood TIMES Westfield Tobacco & News 7-11 of Westfield 7-11 of Mountainside Westfield Mini Mart Kwick Mart Food Store Mountain Deli 108 Elm St. (Leader) 1200 South Ave., W. (Leader/Times) 921 Mountain Ave. (Leader) 301 South Ave., W. (Leader) 190 South Ave. (Times) 2385 Mountain Ave. (Times) 7-11 of Garwood Shoprite Supermarket King's Supermarket Baron's Drug Store Scotch Hills Pharmacy Wallis Stationery Krauszer's 309 North Ave. (Leader) 563 North Ave. (Leader) 300 South Ave. (Leader) 243 E. Broad St. (Leader) 1819 East 2nd St. (Times) 441 Park Ave. (Leader/Times) 727 Central Ave. (Leader) Devil’s Den Eclectic Guests Highlight Record Dinner Turnout By BRUCE JOHNSON Specially Written for The Westfield Leader and The Times This week we’re going to take a Tillman, coach John Wooden. Eric Shaw, boys soccer coach. Johan one-week break from the rigors of Liz McKeon, girls basketball coach Cruyff, Alex Ferguson, Harry WHS athletics, and spend some time (’99). Tommy Hart (grandfather), McAlarney (grandfather). breaking bread with the school’s ath- Derek Jeter, Pat Summitt. Jillian Shirk, future athlete (’26). letes, coaches, alumni and fans. Steve Merrill, historian (’71). Gen- Antonio Brown, Steph Curry, Eli Tonight’s big event is the third erals Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Manning. mythical Devil’s Den Dinner. We Lee, George Patton. Maria Shirk, future athlete (’29). asked WHS senior athletes, coaches, Don Mokrauer, fan (’63). -

Senate and House of Rep- but 6,000 Miles Away, the Brave People Them

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 149 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2003 No. 125 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. minute and to revise and extend his re- minute and to revise and extend his re- The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. marks.) marks.) Coughlin, offered the following prayer: Mr. BLUNT. Mr. Speaker, we come Mr. HOYER. Mr. Speaker, the gen- Two years have passed, but we have here today to remember the tragedy of tleman from Missouri (Mr. BLUNT) is not forgotten. America will never for- 2 years ago and remember the changes my counterpart in this House. It is his get the evil attack on September 11, that it has made in our country. responsibility to organize his party to 2001. But let us not be overwhelmed by Two years ago this morning, early in vote on issues of importance to this repeated TV images that bring back the morning, a beautiful day, much country and to express their views. paralyzing fear and make us vulnerable like today, we were at the end of a fair- And on my side of the aisle, it is my re- once again. Instead, in a moment of si- ly long period of time in this country sponsibility to organize my party to lence, let us stand tall and be one with when there was a sense that there real- express our views. At times, that is ex- the thousands of faces lost in the dust; ly was no role that only the Federal traordinarily contentious and we dem- let us hold in our minds those who still Government could perform, that many onstrate to the American public, and moan over the hole in their lives. -

State of Wisconsin

STATE OF WISCONSIN One-Hundred and Third Regular Session 2:06 P.M. TUESDAY, January 3, 2017 The Senate met. State of Wisconsin Wisconsin Elections Commission The Senate was called to order by Senator Roth. November 29, 2016 The Senate stood for the prayer which was offered by Pastor Alvin T. Dupree, Jr. of Family First Ministries in The Honorable, the Senate: Appleton. I am pleased to provide you with a copy of the official The Colors were presented by the VFW Day Post 7591 canvass of the November 8, 2016 General Election vote for Color Guard Unit of Madison, WI. State Senator along with the determination by the Chair of the Wisconsin Elections Commission of the winners. The Senate remained standing and Senator Risser led the Senate in the pledge of allegiance to the flag of the United With this letter, I am delivering the Certificates of Election States of America. and transmittal letters for the winners to you for distribution. The National Anthem was performed by Renaissance If the Elections Commission can provide you with further School for the arts from the Appleton Area School District information or assistance, please contact our office. and Thomas Dubnicka from Lawrence University in Sincerely, Appleton. MICHAEL HAAS Pursuant to Senate Rule 17 (6), the Chief Clerk made the Interim Administrator following entries under the above date. _____________ Senator Fitzgerald, with unanimous consent, asked that the Senate stand informal. Statement of Canvass for _____________ State Senator Remarks of Majority Leader Fitzgerald GENERAL ELECTION, November 8, 2016 “Mister President-Elect, Justice Kelly, Pastor Dupree, Minority Leader Shilling, fellow colleagues, dear family, and I, Michael L. -

Enriching Families in the Parish Through the Use of Musical Drama

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project Concordia Seminary Scholarship 2-1-2001 Enriching Families in the Parish Through the Use of Musical Drama Wallace Becker Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Becker, Wallace, "Enriching Families in the Parish Through the Use of Musical Drama" (2001). Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project. 109. https://scholar.csl.edu/dmin/109 This Major Applied Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Ministry Major Applied Project by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONCORDIA SEMINARY SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI ENRICHING FAMILIES IN THE PARISH THROUGH THE USE OF MUSICAL DRAMA A MAJOR APPLIED PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY BY REV. WALLACE M. BECKER SPRINGFIELD, MISSOURI FEBRUARY, 2001 To Alvina, my wife, To Jeremy and Andy, my sons. Our family has been a blessing from God. The musical dramas that we have shared have been wonderful family experiences. They have given me great joy. CONTENTS ABSTRACT x INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE: FAMILY CENTERED MINISTRY IN THE CHURCH 4 Introduction 4 The Family is God's Design 8 The Church Was Established By God 22 The Church Is the Family of God 24 Church and Family Working Together 28 The Attitude of the Leaders 32 Church Programs 34 Church Programs That Oppose the Family 40 Adding Family-Friendly Programs 41 Christian Family, The Church in That Place 45 TWO: MUSICAL DRAMA IN THE CHURCH 48 Introduction 48 The Roots of Musical Drama in the Early Christian Church . -

Reducing the Negative Attidudes of Religious Fundamentalists Toward Homosexuals John A

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2009 Reducing the negative attidudes of religious fundamentalists toward homosexuals John A. Frank Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frank, John A., "Reducing the negative attidudes of religious fundamentalists toward homosexuals" (2009). Honors Theses. 1277. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITYOFRICHMOND LIBRARIES llllllllllll~lll~lll~llll!IIIIHlll!llllll~!~ll!II 3 3082 01031 8151 Reducing the Negative Attitudes of Religious Fundamentalists Toward Homosexuals John A. Frank University of Richmond Ctbl~- crys1a1Hoyt, Advisor Kristen Lindgren Don Forsyth Committee Members 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ...................................................................... -3- A bstract. ................................................................................. -4- Introduction .............................................................................. -5- Method Participants ..................................................................... -I!- Measures ...................................................................... -

Mott the Hoople and Ian Hunter: All the Young Dudes - the Biography Free Download

MOTT THE HOOPLE AND IAN HUNTER: ALL THE YOUNG DUDES - THE BIOGRAPHY FREE DOWNLOAD Campbell Devine | 423 pages | 09 Aug 2007 | Cherry Red Books | 9781901447958 | English | London, United Kingdom Ian Hunter (singer) Jonesy and Coop went and when I finally tracked them down for a full report, their eyes were still ricocheting around like pinballs, all fan-boy struck and gloating more than just a little bit. Hunter and Ronson then parted professionally, reportedly due to Hunter's refusal to deal with Ronson's manager, Tony DeFries. The new lineup toured in lateand the concerts were documented on 's Mott the Hoople Live. No trivia or quizzes yet. Ditto Bender, with a pair of his own with the criminally overlooked and underappreciated Widowmaker not the wanky Dee Snider outfit. Greg Reeves marked it as to-read Nov 29, Jane marked it as to-read Jun 07, Mott The Hoople and Ian Hunter: All the Young Dudes - The Biography they were interviewed extensively for the book, following publication both Dale Griffin and Overend Watts disowned the book and were scathing about it and the Mott The Hoople and Ian Hunter: All the Young Dudes - The Biography. An album of the same name was released on Columbia Records in the fall, and it became a hit in the U. Lauren Griffin marked it as to-read Dec 30, Queenonce an opening act for Mott the Hoople, provided backing vocals on one track. Hunter's entry into the music business came after a chance encounter with Colin York and Colin Broom at a Butlin's Holiday Campwhere the trio won a talent competition performing " Blue Moon " on acoustic guitars. -

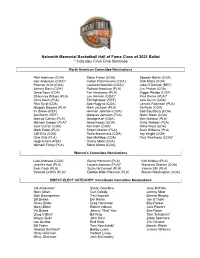

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame Class of 2021 Ballot * Indicates First-Time Nominee North American Committee Nominations Rick Adelman (COA) Steve Fisher (COA) Speedy Morris (COA) Ken Anderson (COA)* Cotton Fitzsimmons (COA) Dick Motta (COA) Fletcher Arritt (COA) Leonard Hamilton (COA)* Jake O’Donnell (REF) Johnny Bach (COA) Richard Hamilton (PLA) Jim Phelan (COA) Gene Bess (COA) Tim Hardaway (PLA) Digger Phelps (COA) Chauncey Billups (PLA) Lou Henson (COA)* Paul Pierce (PLA)* Chris Bosh (PLA) Ed Hightower (REF) Jere Quinn (COA) Rick Byrd (COA) Bob Huggins (COA) Lamont Robinson (PLA) Muggsy Bogues (PLA) Mark Jackson (PLA) Bo Ryan (COA) Irv Brown (REF) Herman Johnson (COA) Bob Saulsbury (COA) Jim Burch (REF) Marques Johnson (PLA) Norm Sloan (COA) Marcus Camby (PLA) George Karl (COA) Ben Wallace (PLA) Michael Cooper (PLA)* Gene Keady (COA) Chris Webber (PLA) Jack Curran (COA) Ken Kern (COA) Willie West (COA) Mark Eaton (PLA) Shawn Marion (PLA) Buck Williams (PLA) Cliff Ellis (COA) Rollie Massimino (COA) Jay Wright (COA) Dale Ellis (PLA) Bob McKillop (COA) Paul Westhead (COA)* Hugh Evans (REF) Danny Miles (COA) Michael Finley (PLA) Steve Moore (COA) Women’s Committee Nominations Leta Andrews (COA) Becky Hammon (PLA) Kim Mulkey (PLA) Jennifer Azzi (PLA) Lauren Jackson (PLA)* Marianne Stanley (COA) Swin Cash (PLA) Suzie McConnell (PLA) Valerie Still (PLA) Yolanda Griffith (PLA)* Debbie Miller-Palmore (PLA) Marian Washington (COA) DIRECT-ELECT CATEGORY: Contributor Committee Nominations Val Ackerman* Simon Gourdine Jerry McHale Marv -

Legislators Endorsement

For Immediate Release Contact: Alanna Conley Monday, March 15 2021 (608) 520-0547 34 STATE LEGISLATORS ENDORSE JILL UNDERLY FOR STATE SUPERINTENDENT HOLLANDALE, Wis. — Pecatonica Area School District Superintendent and candidate for Wisconsin State Superintendent Jill Underly announced today she has received the endorsement of 34 current and former state legislators. See the full list of endorsers on the next page. "Dr. Jill Underly is a steadfast champion of our public schools. Her platform is rooted in equity and her mission to provide every child in Wisconsin the high-quality public education they deserve regardless of their race, ability, gender, orientation, or socio-economic status,” said Sen. LaTonya Johnson (D-Milwaukee). “I know that Jill is the right choice for this important job and I'm proud to endorse her." “I urge everyone to get out and vote for Jill Underly for State Superintendent of Public Instruction,” said Sen. Janet Bewley (D-Mason). “Jill’s lifelong dedication to public education as a teacher, administrator, UW advisor, and as Superintendent of Pecatonica, as well as her previous work with the Department of Public Instruction make her an ideal candidate for this position.” “Dr. Jill Underly has dedicated her life to public education with over 20 years of experience in every facet of public education. Jill has the experience and perspective we need in our next State Superintendent.” said former Sen. Dale Schultz (R-Richland Center). “I know that Jill will do what’s best for our kids every single day she’s in office and she has my wholehearted endorsement in this race.” “Dr. -

Message to the Congress Transmitting Reports of The

1618 Nov. 8 / Administration of George W. Bush, 2001 those who travel abroad for business or vaca- ments have been acts of courage for which tion can all be ambassadors of American val- no one could have ever prepared. ues. Ours is a great story, and we must tell We will always remember the words of it, through our words and through our deeds. that brave man, expressing the spirit of a I came to Atlanta today to talk about an great country. We will never forget all we all-important question: How should we live have lost and all we are fighting for. Ours in the light of what has happened? We all is the cause of freedom. We’ve defeated free- have new responsibilities. dom enemies before, and we will defeat Our Government has a responsibility to them again. hunt down our enemies, and we will. Our We cannot know every turn this battle will Government has a responsibility to put need- take. Yet we know our cause is just and our less partisanship behind us and meet new ultimate victory is assured. We will, no doubt, challenges: better security for our people, face new challenges. But we have our march- and help for those who have lost jobs and ing orders: My fellow Americans, ‘‘Let’s roll.’’ livelihoods in the attacks that claimed so NOTE: The President spoke at 8:03 p.m. at the many lives. I made some proposals to stimu- World Congress Center. In his address, he re- late economic growth which will create new ferred to Kathy Nguyen, a New York City hospital jobs and make America less dependent on worker who died October 31 of inhalation anthrax; foreign oil. -

Cbcopland on The

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND The Legacy of AARON COPLAND Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” rom Boston to Bombay, Tokyo to Toronto, the United States Army Field Band has been thrilling audiences of all ages for more than fifty years. As the pre- mier touring musical representative for the United States Army, this in- Fternationally-acclaimed organization travels thousands of miles each year presenting a variety of music to enthusiastic audiences throughout the nation and abroad. Through these concerts, the Field Band keeps the will of the American people behind the members of the armed forces and supports diplomatic efforts around the world. The Concert Band is the oldest and largest of the Field Band’s four performing components. This elite 65-member instrumental ensemble, founded in 1946, has performed in all 50 states and 25 foreign countries for audiences totaling more than 100 million. Tours have taken the band throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, South America, Europe, the Far East, and India. The group appears in a wide variety of settings, from world-famous concert halls, such as the Berlin Philharmonie and Carnegie Hall, to state fairgrounds and high school gymnasiums. The Concert Band regularly travels and performs with the Sol- diers’ Chorus, together presenting a powerful and diverse program of marches, over- tures, popular music, patriotic selections, and instrumental and vocal solos. The orga- nization has also performed joint concerts with many of the nation’s leading orchestras, including the Boston Pops, Cincinnati Pops, and Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The United States Army Field Band is considered by music critics to be one of the most versatile and inspiring musical organizations in the world. -

2012 Race Information

IDITAROD HISTORY – GENERAL INFO 2012 RACE INFORMATION 40th Race on 100 Year Old Trail TABLE OF CONTENTS Iditarod Trail Committee Board of Directors and Staff………………………………………………… 3 Introduction…………………..……………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Famous Names………………………………..……………………………………………………………….….. 7 1925 Serum Run To Nome…………………………………………………………………………….………. 8 History of the “Widows Lamp”……………………………………………………………………………….. 9 History of the Red Lantern……..…………………………………………………….…………….………… 9 What Does the Word “Iditarod” Mean?………………………………………………………….………… 9 Animal Welfare……………………………………………………………………………………………….……. 10 Dictionary of Mushing Terms………………………………………………….……………………….…….. 11 Iditarod Insider – GPS Tracking Program.………………………….…………………………….……… 12 Idita-Rider Musher Auction……………………………………..…………………………………….……….. 12 2012 Musher Bib Auction…….………………………………………………………………………….……… 12 Jr. Iditarod…………………....…………………………………………………………………………………….. 13 1978-2011 Jr. Iditarod Winners………………………………………………………………………………. 13 1973-2011 Race Champions & Red Lantern Winners………….…………………………………….. 14 2012 Idita-Facts…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 15 40th Race on 100 Year Old Trail……………………………….……………………………………………. 16 2012 Official Map of the Iditarod Trail…………………………………………………………………… 17 Directions from Downtown Anchorage to Campbell Airstrip/BLM ………….………….……… 18 Official Checkpoint Mileages…………………..…………………………………………………….……... 19 2012 Checkpoint Descriptions……………………………….………………………………………….….. 20 Description of the Iditarod Trail……………………………………………………………….….………. 23 2012 Official Race Rules…….………………………………………………………………………………. -

Carpinella Appointed Vice President At

PAID ECRWSS Boston, MA PRSRT STD U.S. Postage ermit No. 55800 P TOWN CRIER April 28, 2017 MILFORD, MASSACHUSETTS Vol. 10 No. 14 Est. 2007 • Mailed FREE to all 12,800 Milford addresses Town Crier Publications Town Street 48 Mechanic MA 01568 Upton, PATRON POSTAL MA 01757 MILFORD, www.TownCrier.us Public Safety Visits ZBA Nips Medical Marijuana Clinic in the Bud Same House By Kevin Rudden his comments. “It’s a family plaza,” the company’s intent and said he Staff Reporter/Columnist Carlson said. would accept a condition that no 40 Times in 27 Months With Sage Biotech indefinitely “It would be a lot easier for retail sales would be allowed. delaying the opening of its medical everyone to swallow,” if the Barton said he searched all over marijuana dispensary at 13 proposed facility was in an isolated Milford for a suitable location Commercial Way in the Bear Hill building with a fence around and “This is what I found.” section of town, Natural Remedies, it, Pyne said. “The location isn’t Attorney John Fernandes likened Inc. of Hopkinton stepped in with acceptable to everyone here.” Pyne the requested facility to having a plans to open one in the nearby went on to comment about the pharmacy in the shopping plaza. Milford Plaza on Medway Rd. marijuana sales business: “We’re in “You’re going to have issues,” (Route 109). The Zoning Board of the Wild West the way these things commented Pasquale Cerasuolo Appeals (ZBA), however, nipped are going.” of 2 Messina St., saying he was a that plan in the bud by voting 4-1 Consigli and several other board retired police officer and security against it, based on the location.