A Journalistic Series About Homosexuality in Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gay Games a Promotional Piece for by Jim Buzinski the First Gay Games, Then Called the Gay Olympic Games, in 1982

Gay Games A promotional piece for by Jim Buzinski the first Gay Games, then called the Gay Olympic Games, in 1982. Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Courtesy Federation of Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Gay Games. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The Gay Games is a quadrennial sporting and cultural event designed for the gay and lesbian community. The brainchild of former Olympic decathlete Tom Waddell, the Games were first held in San Francisco in 1982. Some 1,300 athletes participated in the first competition. Since then, the event has become a lucrative attraction that cities bid for the privilege of hosting. The Games pump millions of dollars into the host city's local economy. Waddell had originally intended to call the competition the Gay Olympics, but nineteen days before the start of the first games the United States Olympic Committee obtained a restraining order, forbidding the use of that name. The USOC asserted that it had sole rights to use the name Olympics. Waddell, noting that the USOC had raised no objections to other competitions using the name, told Sports Illustrated: "The bottom line is that if I'm a rat, a crab, a copying machine or an Armenian I can have my own Olympics. If I'm gay, I can't.'' Waddell, who died from complications of AIDS in 1987, conceived the Games as a means of promoting the spirit of inclusion and healthy competition in athletics. As his biographer Dick Schaap explains, "Tom wanted to emphasize that gay men were men, not that they were gay, and that lesbian women were women, not that they were lesbians. -

Senate and House of Rep- but 6,000 Miles Away, the Brave People Them

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 149 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 11, 2003 No. 125 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. minute and to revise and extend his re- minute and to revise and extend his re- The Chaplain, the Reverend Daniel P. marks.) marks.) Coughlin, offered the following prayer: Mr. BLUNT. Mr. Speaker, we come Mr. HOYER. Mr. Speaker, the gen- Two years have passed, but we have here today to remember the tragedy of tleman from Missouri (Mr. BLUNT) is not forgotten. America will never for- 2 years ago and remember the changes my counterpart in this House. It is his get the evil attack on September 11, that it has made in our country. responsibility to organize his party to 2001. But let us not be overwhelmed by Two years ago this morning, early in vote on issues of importance to this repeated TV images that bring back the morning, a beautiful day, much country and to express their views. paralyzing fear and make us vulnerable like today, we were at the end of a fair- And on my side of the aisle, it is my re- once again. Instead, in a moment of si- ly long period of time in this country sponsibility to organize my party to lence, let us stand tall and be one with when there was a sense that there real- express our views. At times, that is ex- the thousands of faces lost in the dust; ly was no role that only the Federal traordinarily contentious and we dem- let us hold in our minds those who still Government could perform, that many onstrate to the American public, and moan over the hole in their lives. -

The Relationship Between Foot-Ball Impact with Kick Outcome

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FOOT-BALL IMPACT AND KICK OUTCOME IN FOOTBALL KICKING Submitted to College of Sport and Exercise Science VICTORIA UNIVERSITY In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By JAMES PEACOCK 2018 Principal supervisor: Dr. Kevin Ball Associate supervisor: Dr. Simon Taylor I Abstract Across the football codes, kicking is the main skill used to score goals and pass between team members. Kicking with high ball velocity and high accuracy is required to kick to targets at far distances or reach a submaximal target in less time. The impact phase is the most important component of the kicking action: it is the only time a player forcefully contacts the ball to produce the flight path. Ensuring high impact efficiency and the appropriate combination of flight characteristics are imparted onto the ball during foot-ball impact is important for successful kicking. The aim of this thesis was to determine how foot-ball impact characteristics influences impact efficiency, ankle plantarflexion, ball flight characteristics and kicking accuracy. By using a mechanical kicking machine to systematically explore impact characteristics and performing an intra-individual analysis of human kickers, high-speed-video analysis of foot-ball impact found impact characteristics influenced impact efficiency, ankle plantarflexion, ball flight characteristics, and kicking accuracy. Increasing ankle joint stiffness, impact locations on the foot closer to the ankle joint, altering foot-ball angle and reducing foot velocity each increased impact efficiency. These results supported the coaching cue ‘maintaining a firm ankle’ during impact as effective at increasing impact efficiency. The impact location between the foot and ball across the medial-lateral direction, foot-ball angle and foot trajectory were each identified as influential to ball flight characteristics and/ or kicking accuracy. -

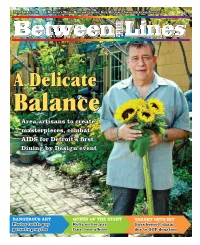

Area Artisans to Create Masterpieces, Combat AIDS for Detroit's First

PRIDESOURCE.COM MICHIGAN’S WEEKLY NEWS FOR LESBIANS, GAYS, BISEXUALS, TRANSGENDERS AND FRIENDS 1831 08.05.10 A Delicate Balance Area artisans to create masterpieces, combat AIDS for Detroit’s first Dining by Design event DANGEROUS ART QUEEN OF THE NIGHT TARGET GETS HIT Photos tackle gay Kelis on her gay Gays boycott chain parenting myths fans, new album due to GOP donation 2 Between The Lines • August 5, 2010 August 5, 2010 Vol. 1831 • Issue 673 Publishers Susan Horowitz Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi Associate News Editor Jessica Carreras Arts & Theater Editor 12 19 21 34 Donald V. Calamia Editorial Intern 13 NJ Supreme Court rejects 25 Curtain Calls Lucy Hough News same-sex marriage case Reviews of “The Last Night of Ballyhoo” and Contributing Writers Lawsuit filed over whether state’s civil union “Herstory Repeats Herself: A Trilogy in 3-D” Charles Alexander, Paul Berg, Wayne Besen, 5 Between Ourselves law provides equal treatment for gay couples D.A. Blackburn, Dave Brousseau, Tony O’Rourke-Quintana Michelle E. Brown, John Corvino, 26 Happenings Jack Fertig, Joan Hilty, Lisa Keen, Jim Larkin, Jason A. Michael, 14 International News Briefs Anthony Paull, Crystal Proxmire, 6 A Delicate Balance Gay weddings begin in Argentina Bob Roehr, Gregg Shapiro, Jody Valley, Beauty of art meets darkness of disease Rear View D’Anne Witkowski, Imani Williams at Detroit’s first Dining by Design HIV/AIDS Rex Wockner, Dan Woog fundraiser Opinions Contributing Photographer 28 Dear Jody Andrew -

Copenhagen 2009 World Outgames

love of freedom -freedom to love copenhagen 2009 world outgames copenhagen 2009 world outgames www.copenhagen2009.org ‘‘Copenhagen is backing World Outgames 2009. We invite you to join us and value your participation and support in making this vitally meaningful event possible. World Outgames 2009 demonstrates the spirit of tolerance and acceptance that makes Copenhagen one of the best cities in the world.” Ritt Bjerregaard, Lord Mayor of Copenhagen ‘‘World Outgames 2009 will strengthen Denmark’s reputa- tion as a tolerant society and a creative nation. The unique combination of sports, culture and human rights makes World Outgames the ideal platform to highlight the many positive features of Denmark that make it attractive to tourists, business people and other players in the global economy.” The Danish Minister of Culture, Brian Mikkelsen The World Outgames Equation The last week of July 2009 + Danish summer at its best + Denmark’s vibrating capital + competitions in 40 sports + a human rights conference with participants from over 50 countries + loads of free cultural programmes on the streets + 8,000 lesbians, gays and those in-between + 20,000 of their friends, family and/or partners + artists great and small and a good handful of DJ’s + a film festival, dance festival and choir festival + party fireworks across the skies of Copenhagen + political speeches and new legislation + barbeque parties at Amager Beach + a whole new story about Denmark + 10 inter- 4 national balls + ambassadors, ministers and city councillors flying in from -

From Brighton to Helsinki

From Brighton to Helsinki Women and Sport Progress Report 1994-2014 Kari Fasting Trond Svela Sand Elizabeth Pike Jordan Matthews 1 ISSN: 2341-5754 Publication of the Finnish Sports Confederation Valo 6/2014 ISBN 978-952-297-021-3 2 From Brighton to Helsinki Women and Sport Progress Report 1994-2014 Kari Fasting, Trond Svela Sand, Elizabeth Pike, Jordan Matthews IWG Helsinki 2014 1 Foreword: Address from the IWG Co-Chair 2010 – 2014 in sport at all levels and in all functions and roles. The variety and number of organisations engaged in this work is remarkable, and the number con- tinues to grow. Twenty years marks a point in the history of the Brighton Declaration, where we can and must review the implementation of this document. The ‘From Brighton to Helsinki’ IWG Progress Report provides examples of initiatives that have been undertaken by Brighton Declaration signatories and Catalyst-subscribers to empower women. In spite of these efforts, the latest data shows that in some areas progress has been limited. The IWG Progress Report offers a chance to evaluate the Dear friends, measures already taken and sheds light on the Twenty years have passed quickly. I wonder if new goals and actions that we must adopt in order to take further steps toward our mission: ‘Empow- Women and Sport in 1994 in Brighton, UK, ever ering women – advancing sport’. imagined how things would have developed by 2014. The Brighton Declaration on Women and On behalf of the International Working Group on Sport has been endorsed by more than 400 or- Women and Sport (IWG) I would like to express ganisations worldwide. -

National News in ‘09: Obama, Marriage & More Angie It Was a Year of Setbacks and Progress

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Dec. 30, 2009 • vol 25 no 13 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Joe.My.God page 4 LGBT Films of 2009 page 16 A variety of events and people shook up the local and national LGBT landscapes in 2009, including (clockwise from top) the National Equality March, President Barack Obama, a national kiss-in (including one in Chicago’s Grant Park), Scarlet’s comeback, a tribute to murder victim Jorge Steven Lopez Mercado and Carrie Prejean. Kiss-in photo by Tracy Baim; Mercado photo by Hal Baim; and Prejean photo by Rex Wockner National news in ‘09: Obama, marriage & more Angie It was a year of setbacks and progress. (Look at Joining in: Openly lesbian law professor Ali- form for America’s Security and Prosperity Act of page 17 the issue of marriage equality alone, with deni- son J. Nathan was appointed as one of 14 at- 2009—failed to include gays and lesbians. Stone als in California, New York and Maine, but ad- torneys to serve as counsel to President Obama Out of Focus: Conservative evangelical leader vances in Iowa, New Hampshire and Vermont.) in the White House. Over the year, Obama would James Dobson resigned as chairman of anti-gay Here is the list of national LGBT highlights and appoint dozens of gay and lesbian individuals to organization Focus on the Family. Dobson con- lowlights for 2009: various positions in his administration, includ- tinues to host the organization’s radio program, Making history: Barack Obama was sworn in ing Jeffrey Crowley, who heads the White House write a monthly newsletter and speak out on as the United States’ 44th president, becom- Office of National AIDS Policy, and John Berry, moral issues. -

Burris, Durbin Call for DADT Repeal by Chuck Colbert Page 14 Momentum to Lift the U.S

THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 Mar. 10, 2010 • vol 25 no 23 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com Burris, Durbin call for DADT repeal BY CHUCK COLBERT page 14 Momentum to lift the U.S. military’s ban on Suzanne openly gay service members got yet another boost last week, this time from top Illinois Dem- Marriage in D.C. Westenhoefer ocrats. Senators Roland W. Burris and Richard J. Durbin signed on as co-sponsors of Sen. Joe Lie- berman’s, I-Conn., bill—the Military Readiness Enhancement Act—calling for and end to the 17-year “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy. Specifically, the bill would bar sexual orien- tation discrimination on current service mem- bers and future recruits. The measure also bans armed forces’ discharges based on sexual ori- entation from the date the law is enacted, at the same time the bill stipulates that soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guard members previ- ously discharged under the policy be eligible for re-enlistment. “For too long, gay and lesbian service members have been forced to conceal their sexual orien- tation in order to dutifully serve their country,” Burris said March 3. Chicago “With this bill, we will end this discrimina- Takes Off page 16 tory policy that grossly undermines the strength of our fighting men and women at home and abroad.” Repealing DADT, he went on to say in page 4 a press statement, will enable service members to serve “openly and proudly without the threat Turn to page 6 A couple celebrates getting a marriage license in Washington, D.C. -

View Entire Issue As

4'1 Trir May, 2005 IAD Vol. 4, Issue 5 MAGAZINE YERSARY PARTY VIifeRE Freeree Darts •. Free Food • Raffle Enterte:i.l`.',i:1....'t,1l.l\.I,l\.i.-l`\: uiHE Mondays 2.I.I 0-$ OroI'm@I" TuO§.rues. - Fri.[1,i. 2.4.12.4.icocneCocktails 5-8pm54rm Thursday 26th Hey Wednesdays Milwaukee... SiS`°gnffi#uemo8 Ott Miller Bottles POSY Bum-Close PARTY Thursdays S3.50sosoffiejfmaDS Cosmopolitans Bum-Close 3aturdairSaturdays S4 Long Island a&ngngFT8Ei#ne Long Beach Iced Teas 5-9pm Sundays seGuunao.mm open-Close unteeactg Omen @ 51lm llailu =j= i' = lps Requ]red Ail ai= ± i•i i ii qune5843 awn= - —'Al PrideFest' WISCONSIN'S IN MILWAUKEE SUMMERFEST GROUNDS SATURDAY : JASON STUART, T R YN R P SUNDAY: PAMELA MEANS, JADE ESTEBAN ESTRADA, SOPHIE B. HAWKINS JUNE 11 & 12 WWW.PRIDEFEST.COM • CITY MILWAUKEE LGBT COMMUNITY CENTER (12t 00 ) ro.,1 TIle Official Beer Of Priderest 11110 . OUI IP WI XING° • CASI, WINDY CITY MEDIA GROUP 4:110 rre CAGE scene 99 WMY X MIDWEST) a AIRIPOIFS WYNDHAM MILWAUKEE CENTER- --j` ` ji--` illfr:BOTCAMPSALOON.COM 0,* Supporter Of The Milwaukee Pride Parade GET INVOLVED! 1712 W. PiercePlerce StSI One I)lockblock northnorth of NationalNational Ave.Ave. Friday - Ma) 7th Great i .1.ces :ers* 2nd Annul Ready [0 kJ .- Beer 8 SodaSoda i iBust Bust i,u 11()(E1 CAM[1_),-:J rriday Mayriath eat Nit de ade SALOON •\1 i±,-,.I-...-€......-I::*--I..i!:iit en SpeFlalSpec]a] GuesTslll6tTli-s!!! !IWO ITUK V• a ' 209 E. National Aye, Milwaukee, WI 53204 WVf4V.1AZZB4P11.COM k I 4 !NI (P` Hoed wn YEAR f;DIllz_? I 6ANNIVERSARY PARTY SUNDAY,SUNIIAT,MAl'15'l'H.4".t`L MAY 15'111 1411- CL FUN .FOOD Foon .PRIZES mlzHs .• r]o6oGOGO HoysBOYS Special Appearance ByBy Miller lite RiverwestRiverwest Accordian ClubClub 7-9pm7-9pm Bottles MemorialMemorial DayDay WeekendWeekend 17()AitiE_h]-I PAitTIT!PART On The PatioPatio .• Sat.Sat. -

From Brighton to Helsinki: Women and Sport Progress Report 1994

From Brighton to Helsinki Women and Sport Progress Report 1994-2014 Kari Fasting Trond Svela Sand Elizabeth Pike Jordan Matthews 1 ISSN: 2341-5754 Publication of the Finnish Sports Confederation Valo 6/2014 ISBN 978-952-297-021-3 2 From Brighton to Helsinki Women and Sport Progress Report 1994-2014 Kari Fasting, Trond Svela Sand, Elizabeth Pike, Jordan Matthews IWG Helsinki 2014 1 Foreword: Address from the IWG Co-Chair 2010 – 2014 in sport at all levels and in all functions and roles. The variety and number of organisations engaged in this work is remarkable, and the number con- tinues to grow. Twenty years marks a point in the history of the Brighton Declaration, where we can and must review the implementation of this document. The ‘From Brighton to Helsinki’ IWG Progress Report provides examples of initiatives that have been undertaken by Brighton Declaration signatories and Catalyst-subscribers to empower women. In spite of these efforts, the latest data shows that in some areas progress has been limited. The IWG Progress Report offers a chance to evaluate the Dear friends, measures already taken and sheds light on the Twenty years have passed quickly. I wonder if new goals and actions that we must adopt in order the participants of the first World Conference on to take further steps toward our mission: ‘Empow- Women and Sport in 1994 in Brighton, UK, ever ering women – advancing sport’. imagined how things would have developed by 2014. The Brighton Declaration on Women and On behalf of the International Working Group on Sport has been endorsed by more than 400 or- Women and Sport (IWG) I would like to express ganisations worldwide. -

Kiwidex Balls Hoops

KIWIDEX RUNNING / WALKING 181 Balls, Hoops and Odds & Ends www.sparc.org.nz 182 Section Contents Suggestions 183 Cats and Pigeons 184 “Geared Up” Relays 186 Team Obstacle Relay 190 Move On Relay 192 Hoop Work 194 Keep the Bucket Full 196 Rob the Nest 197 Triangles 199 Pass and Follow 200 Corner Spry 201 Tunnel Ball 202 Bob Ball 205 Multiple Relay 206 Two vs Two 207 50/50 208 Running Circle Pass 209 Four Square 210 Eden Ball 211 In and Out 212 KIWIDEX BALLS, HOOPS AND ODDS & ENDS 183 Suggestions Balls and hoops provide the basis for many games, activities and relays in the daily physical activity session. Any of the following items can be successfully incorporated into relays and activities: • Balls – all shapes and sizes, hard or soft • Batons • Hoops • Tenniquoits • Benches • Bean Bags • Frisbees • Padder tennis bats • Skipping ropes • Children’s shoes, if all else fails. Remember when using balls that they can be thrown, rolled, kicked, bounced, dribbled with feet, carried, held between legs or under chin, batted along the ground. Soft or spongy balls are safe to use in halls or in open spaces in the classroom. All the equipment named above lends itself to relay work. After working through the following ideas, teachers will be able to develop many additional relay sequences and challenge the children to devise their own relay sequences. The daily physical activity session is not a time to teach specifi c skills. Use skills the children have already been introduced to. The daily physical activity session does give another opportunity to practise skills taught during physical education lessons. -

Reducing the Negative Attidudes of Religious Fundamentalists Toward Homosexuals John A

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2009 Reducing the negative attidudes of religious fundamentalists toward homosexuals John A. Frank Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frank, John A., "Reducing the negative attidudes of religious fundamentalists toward homosexuals" (2009). Honors Theses. 1277. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1277 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITYOFRICHMOND LIBRARIES llllllllllll~lll~lll~llll!IIIIHlll!llllll~!~ll!II 3 3082 01031 8151 Reducing the Negative Attitudes of Religious Fundamentalists Toward Homosexuals John A. Frank University of Richmond Ctbl~- crys1a1Hoyt, Advisor Kristen Lindgren Don Forsyth Committee Members 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ...................................................................... -3- A bstract. ................................................................................. -4- Introduction .............................................................................. -5- Method Participants ..................................................................... -I!- Measures ......................................................................