Pratt Center's Task 2 Research Report, Drafted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

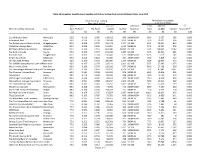

3A Expanded Small Business Lending

Table 3A Expanded. Small Business Lending Institutions in New York Using Call Report Data, June 2012 Small Business Lending Micro Business Lending (less than $ million) (less than $ 100k) Total Amount Institution Total Amount CC Name of Lending Institution City Rank TA Ratio1 TBL Ratio1 (1,000) Number Asset Size Rank (1,000) Number Amount/TA1 (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10) Catskill Hudson Bank Monticello 92.5 0.419 1.000 148,102 686 100M-500M 80.0 8,557 289 0.000 Adirondack Bank Utica 90.0 0.220 0.704 128,588 1,029 500M-1B 95.0 19,322 594 0.000 The Bridgehampton National Bank Bridgehampton 87.5 0.169 0.570 236,278 1,377 1B-10B 92.5 35,912 864 0.000 Watertown Savings Bank Watertown 85.0 0.208 0.690 105,854 1,012 500M-1B 87.5 14,901 596 0.000 NBT Bank, National Association Norwich 85.0 0.139 0.512 823,680 10,927 1B-10B 92.5 128,045 7,142 0.000 The Bank of Castile Castile 85.0 0.150 0.574 151,215 1,385 1B-10B 92.5 23,521 821 0.000 Riverside Bank Poughkeepsie 85.0 0.495 0.704 100,441 627 100M-500M 82.5 7,279 282 0.000 Empire State Bank Newburgh 85.0 0.414 0.864 66,385 431 100M-500M 70.0 3,038 237 0.000 Shinhan Bank America New York 82.5 0.197 0.307 189,889 1,175 500M-1B 82.5 18,025 494 0.001 The Suffolk County National Bank of RRiverhead 82.5 0.137 0.379 213,111 2,161 1B-10B 87.5 27,695 1,375 0.000 Woori America Bank New York 82.5 0.199 0.379 195,042 977 500M-1B 80.0 17,498 390 0.004 The Canandaigua National Bank and TCanandaigua 82.5 0.143 0.418 259,182 4,294 1B-10B 92.5 47,842 3,347 0.000 The Mahopac National Bank Brewster 82.5 -

New York City's Small Public Schools: Opportunities for Achievement. INSTITUTION New York Networks for School Renewal, NY

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 430 767 RC 021 998 AUTHOR Brownell, Carol, Ed.; Libby, Joan TITLE New York City's Small Public Schools: Opportunities for Achievement. INSTITUTION New York Networks for School Renewal, NY. SPONS AGENCY Annenberg Foundation, St. Davids, PA. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 24p.; Other funding by the New York City Board of Education; Time Warner, Inc.; Aaron Diamond Foundation; Charles Hayden Foundation; Ford Foundation; The Chase Manhattan Foundation; Carnegie Corporation of New York; Stella and Charles Guttman Foundation; Viacom, Inc.; and Nippon Steel U.S.A., Inc. Photographs and map may not reproduce adequately. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; Diversity (Student); Educational Change; Educational Environment; Educational Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; *Outcomes of Education; Parent Participation; Participative Decision Making; Partnerships in Education; Public Schools; *School Community Relationship; *Small Schools; *Urban Schools IDENTIFIERS *New York City Board of Education; *New York Networks for School Renewal; Reform Efforts ABSTRACT In 1994, four New York City school reform organizations joined to form the New York Networks for School Renewal (NYNSR) and received the first Annenberg Challenge urban grant. NYNSR goals are to expandthe number of small, excellent public schools in New York City neighborhoods, particularly those with few educational options; encourage the spreadof practices that help students succeed; build supportive small school networks; and advocate for increased school autonomy. Whether as new schools or as large schools redesigned into small units, small scale has been the key. NYNSR schools average 300 students. Many schools utilize servicelearning and internships, and all have partnerships with local organizations and universities to connect students to the responsibilities of citizenship and work. -

Testimony from Nycha Chairman John B. Rhea Ne W Yor K City Hous Ing Authority Real Property Use As S E Mb Ly Committe E on Hous Ing Friday, March 15, 2013 – 11:00Am

TESTIMONY FROM NYCHA CHAIRMAN JOHN B. RHEA NE W YOR K CITY HOUS ING AUTHORITY REAL PROPERTY USE AS S E MB LY COMMITTE E ON HOUS ING FRIDAY, MARCH 15, 2013 – 11:00AM Chairman Keith Wright, distinguished members of the Committee, and to all the members of the State Assembly, I am John B. Rhea, Chairman of the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). Joining me this morning is Fred Harris, Executive Vice President for Real Estate Development. Thank you for the opportunity to discuss with you our plan to develop new mixed-income housing on NYCHA land. I will describe the challenges that necessitate action on this front; our unique opportunity to reinvest in public housing; and our ongoing engagement of residents, elected officials, and other important stakeholders. Most importantly, I will explain how the plan will benefit NYCHA residents and communities across the City. The Need As we have shared with the members of this committee – as well as other state and local elected officials, advocacy groups, concerned non-profits, and the nearly 630,000 New Yorkers we serve – NYCHA faces serious challenges, including an aging housing stock and a waiting list that only grows longer as more striving families come to our City in search of opportunity and affordable housing. As Mayor Bloomberg announced yesterday, the City’s population has increased by over 160,000 people since 2010, and NYCHA can be sure that many of these newcomers will look to us as a vital resource to help start their lives here. In addition, we’ve seen a dramatic change in the assistance we receive from our partners in government, including the total elimination of state funding and a steady and precipitous decline in funding from the federal government, our principal source of capital and operating dollars. -

NYCHA Journal.Qxd

First-Class U. S . Postage Paid New York, NY Permit No. 4119 Vol. 39, No. 4 www.nyc.gov/nycha APRIL 2009 ATTAIN Lab Opens At Drew- Hamilton Community Center The digital divide is getting smaller! A grand opening ceremony was held for the New York City Housing Authority’s (NYCHA’s) fifth ATTAIN lab which opened on February 27th at the Drew-Hamilton Houses Community Center in Harlem, with a traditional ribbon- cutting. ATTAIN stands for Advanced Technology Training and Information Networking and the goal of the program, which is funded by the State Legislature, is to increase access to new technologies in economically challenged neighborhoods. There are 37 ATTAIN labs throughout New York State, administered by the State University of New York’s University (SUNY’s) Center for Academic and Workforce Development (UCAWD). The Drew-Hamilton Grand Opening was hosted by Assembly Member Keith L.T. Wright, the UCAWD and SUPPORT City Council Members Melissa Mark Viverito, Albert Vann, NYCHA Chairman Ricardo NYCHA. Among the distinguished guests who spoke were NYCHA Elías Morales, NYCHA Secretary Vilma Huertas, and City Council Member Diana Reyna at Chairman Ricardo Elías Morales, Assembly Member Wright, Drew NYCHA’s Annual Legislative Breakfast. Hamilton Resident Association President David Welch and UCAWD Interim Director William Chalmers. In his remarks, Chairman Morales congratulated Mr. Welch on obtaining his GED at the NYCHA NOW MORE THAN EVER! ATTAIN Lab at NYCHA’s Polo Grounds Community Center in NYCHA’s Annual Legislative Breakfast Manhattan, saying he was an inspiration. The lab will provide quali- By Eileen Elliott fied facilitators and training for over 30 academic, occupational, and life skills courses, utilizing 24 state-of-the-art workstations with MEMBERS OF THE CITY COUNCIL AND NEW YORK CITY HOUSING AUTHORITY (NYCHA) RESIDENTS WHO broadband Internet connectivity. -

Community Involvement in Redevelopment After the Expiration of Urban Renewal Plans

Renewing Renewal: Community Involvement in Redevelopment After the Expiration of Urban Renewal Plans A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of Architecture, Planning and Preservation COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Urban Planning by Caroline Thompson May 2020 Abstract Communities impacted by urban renewal in the mid-twentieth century were largely unable to stop the changes brought to their neighborhoods. The plans that operationalized urban renewal remained in place for over 40 years, with significant legislative, legal, and financial effort required to make any alterations. In New York City, many of the urban renewal areas and their governing plans have since expired, ushering in market-driven development and neighborhood changes. This thesis uses a mixed-methods approach to analyze the subsequent built environment changes and to explore community involvement through case studies of redevelopment in the former Seward Park Extension Urban Renewal Area (SPEURA) and Two Bridges Urban Renewal Area (TBURA). While many lots remain unchanged since the urban renewal era, those that have changed reflect local development preferences or the results of major rezonings. The case studies reveal the wide variety of methods of community involvement in site redevelopment, with implications for future participation in redevelopment in the city. Key words: urban renewal, participation, Two Bridges, Essex Crossing, Large-Scale Developments ii Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... -

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(Es)

Manhattan Year BA-NY H&R Original Purchaser Sold Address(es) Location Remains UN Plaza Hotel (Park Hyatt) 1981 1 UN Plaza Manhattan N Reader's Digest 1981 28 West 23rd Street Manhattan Y NYC Dept of General Services 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Summit Hotel 1981 51 & LEX Manhattan N Schieffelin and Company 1981 2 Park Avenue Manhattan Y Ernst and Company 1981 1 Battery Park Plaza Manhattan Y Reeves Brothers, Inc. 1981 104 W 40th Street Manhattan Y Alpine Hotel 1981 NYC West Manhattan * Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Brooks Brothers 1982 1120 Ave of Amer. Manhattan Y Care 1982 660 1st Ave. Manhattan Y Sanwa Bank 1982 220 Park Avenue Manhattan Y City Miday Club 1982 140 Broadway Manhattan Y Royal Business Machines 1982 Manhattan Manhattan * Billboard Publications 1982 1515 Broadway Manhattan Y U.N. Development Program 1982 1 United Nations Plaza Manhattan N Population Council 1982 1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza Manhattan Y Park Lane Hotel 1983 36 Central Park South Manhattan Y U.S. Trust Company 1983 770 Broadway Manhattan Y Ford Foundation 1983 320 43rd Street Manhattan Y The Shoreham 1983 33 W 52nd Street Manhattan Y MacMillen & Co 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Solomon R Gugenheim 1983 1071 5th Avenue Manhattan * Museum American Bell (ATTIS) 1983 1 Penn Plaza, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y NYC Office of Prosecution 1983 80 Center Street, 6th Floor Manhattan Y Mc Hugh, Leonard & O'Connor 1983 Manhattan Manhattan * Keene Corporation 1983 757 3rd Avenue Manhattan Y Melhado, Flynn & Assocs. 1983 530 5th Avenue Manhattan Y Argentine Consulate 1983 12 W 56th Street Manhattan Y Carol Management 1983 122 E42nd St Manhattan Y Chemical Bank 1983 277 Park Avenue, 2nd Floor Manhattan Y Merrill Lynch 1983 55 Water Street, Floors 36 & 37 Manhattan Y WNET Channel 13 1983 356 W 58th Street Manhattan Y Hotel President (Best Western) 1983 234 W 48th Street Manhattan Y First Boston Corp 1983 5 World Trade Center Manhattan Y Ruffa & Hanover, P.C. -

The C Oop Er Union

Founded by inventor, industrialist and philanthropist Peter Cooper in 1859, The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art offers an unparalleled education in art, architecture and engineering, and gives every admitted student a full-tuition scholarship. Believing that an “education of the first rank” should be “as free as air and water,” Peter Cooper, who himself had less than a year THE COOPER UNION of formal schooling, established The Cooper Union to offer a free education to working-class men and women without regard to gender, race, religion or economic status. A century and a half later, The Cooper Union is ranked among the finest American colleges. It remains a private institution with a public mission: To prepare gifted students to make enlightened contributions to the cultural and scientific life of our great urban centers. RANKINGS The rigor of The Cooper Union’s academic programs has made it one of the top-ranked institutions of higher education in the nation in all categories. • Ranked Best Baccalaureate College (north) by U.S. News and World Report • Ranked third in the nation among Undergraduate Engineering Colleges by U.S. News and World Report; ranked first in undergraduate engineering colleges in chemical engineering • Ranked third in research culture among architecture schools worldwide in a survey by the Key Centre for Architectural Sociology • Listed among the Best Design Schools for Creative Talent by Business Week • Listed among the Nation’s 25 Hottest Universities by the Newsweek-Kaplan College Guide • Listed -

2018 Annual Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Company Profile 4 Vision, Mission, and Service Promise 5 Economic Report and Forecast 6 Message from the Chairman 8 Q&A with the President and CEO ABOUT 10 Products and Services THE 13 Financial Highlights 14 Operational Highlights COVER 20 Corporate Social Responsibility OUR LEAVES 22 Corporate Governance OF CHANGE 32 Consumer Protection 36 Table of Organization New thinking is leading the transformed business of Bank of 38 Board of Directors Commerce in a digitized industry. 51 Senior Executive Team The theme and design reflect our 55 Management Committees new approach to a seamless banking 57 Risk Management experience. The convergence of multiple digital tools and platforms in 68 Capital Management our digitized leaves reflects how the 72 Internal Audit Division Report brand empowers the customers of the future. 73 Statement of Management's Responsibility for Financial Statements 74 Audited Financial Statements ABOUT OUR PAPER 75 Report of Independent Auditors 78 Statements of Financial Position The 2018 Bank of Commerce Annual report cover and main pages were 80 Statements of Income printed on Tocatta paper certified 81 Statements of Comprehensive Income by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). The FSC certification ensures 82 Statements of Changes in Equity that materials come from responsibly 84 Statements of Cash Flows managed forests that provide environmental, social and 86 Notes to the Financial Statements economic benefits. Kodak Sonora process-free plates, 209 Senior Officers non-petroleum-based soy ink, and 212 Branch / ATM Directory a Heidelberg carbon neutral offset press were utilized in the printing 217 Annex A - Related Party Transactions of this report. -

Baruch & Baruch Addition

New York City T ST S Wald AN HousingTO Authority F N F S I T # R 140 E 17 H Baruch & Baruch Houses AdditionS # E H 130 OUS TON 170T 85 0 170 Feet ST S S L TA T N # 120 P # T TO 120 I N 16 H P S T 105 # C R # # 9 U T R D 110 S 110 A R 10 # B N I D 95 Lavanburg Homes G F T N S A 605 M # A I 90 # B Gompers R 1 M # 15 D # U H 90 595 L 80 # C O U C 79 R # # 8 A 80 11 B 79GAR # # 75 577 19 # 7 2 Baruch Houses Addition 72 # # 571 72 # 5 18 # T 70 I X 60# 555 E 296 # B 14 # N # 298# D D R EL EL 3 A A 288# # D N N 50 12 CE CE 13 549 Y S Y S R T WI T # D LL F IAM 64# SB 292 W UR 308# ILL G 5 R IA BR # D Legend DE MS AP # L B P 6 R AN UR R W 60 R C G IL D D E L 312 NYCHA Tax Lot BoundaryY BR IA 525 S M F R T A # PP SB R U D NYCHA Buildings with Building & Address Numbers R G B R A F PP 4 W Water R #521 B 4 L R O H O L T ParksM and Open Space T I S E P S S X T T R H E R N S D Streets C T E B O V S U S R I S I N R Buildings N D R N W I R ◄ A A E D F E B G Entrance L C µ N R A D M F BARUCH BLDG# BIN # M SH# ADDRESS ZIP CODE BLOCK LOT AMP# FACILITY PLAYGROUND (MANAGED BY NYC DEPARTMENT OF PARKS & 68 BARUCH DRIVE 10002 323 1 NY005010600 RECREATION) COMMUNITY CENTER/ SETTLEMENT MAIL ROOM/ ROOFTOP LEASE 1 1078027 M 001 605 FDR DRIVE 10002 323 1 NY005010600 LOCATION 1 1078027 M 002 595 FDR DRIVE 10002 323 1 NY005010600 2 1078028 M 003 577 FDR DRIVE 10002 323 1 NY005010600 ROOFTOP LEASE LOCATION 2 1078028 M 004 571 FDR DRIVE 10002 323 1 NY005010600 STOVE ROOM 3 1078029 M 005 555 FDR DRIVE 10002 323 1 NY005010600 GLAZIERS SHOP 3 1078029 M 006 549 FDR DRIVE -

216 41 Cooper Square 89 Abyssinian Baptist Church 165 Alimentation 63

216 index 41 Cooper Square 89 Angel’s Share 92 The Half King Bar & Attaboy 56 Restaurant 83 A Bar 54 127 The Vig Bar 63 Bar Veloce 93 Verlaine 57 Abyssinian Baptist Bembe 173 White Horse Tavern 74 Church 165 Bemelmans Bar 147 Baseball 206 Alimentation 63, 75, 84, Blind Tiger Ale House 73 Basketball 206 93, 102, 157 d.b.a. East Village 93 Bateau 197 American Museum of Dos Caminos 102 Battery Maritime Natural History 153 Gallow Green 83 Building 46 Apollo Theater 164 Great Hall Balcony Bar 147 Battery Park 46 Appartements 184 Henrietta Hudson 74 Hudson Common 128 Battery Park City 41 Appellate Division Hudson Malone 118 Beacon Theatre 156 Courthouse of the New Jake’s Dilemma 156 York State Supreme Bedford Avenue 171 La Birreria 102 Belvedere Castle 136 Court 95 Le Bain 83 Bethesda Fountain & Argent 199 Library Bar 128 Terrace 135 Astoria 175 McSorley’s Old Ale Astor Place 88 House 93 Bijouteries 119 Auberges de Paddy Reilly’s Music Birdland 128 jeunesse 185 Bar 102 Blue Note 74 Paris Café 40 Boerum Hill 171 Autocar 183 Pegu Club 63 Bow Bridge 136 Avery Architectural & Please Don’t Tell 93 Fine Arts Library 162 Roof Garden Café and Bowery Ballroom 57 Avion 180 Martini Bar 147 British Empire Sake Bar Decibel 93 Building 109 B Schiller’s Liquor Bar 57 Broadway 120 Shalel Lounge 156 Bronx 176 Banques 199 Sky Terrace 128 Bronx Zoo 177 Bars et boîtes S.O.B.’s 63 Brookfield Place 42 de nuit 200 The Brooklyn Barge 173 68 Jay Street Bar 173 The Dead Rabbit Grocery Brooklyn 168 Abbey Pub 156 and Grog 40 Brooklyn Botanic Aldo Sohm Wine Bar 127 The -

FINAL LESON DEIS and 78-313 Critique

LESON Zoning and DEIS Critique Submission Robert Dobruskin, AICP, Director Office of City Planning 120 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10271 Re: Critique of the Two Bridges Large Scale Residential Development On Grounds of Failure to Comply with NYC Zoning Resolutions and Inadequate Assessment of Adverse Impacts in Draft Environmental Impact Statement “Two Bridges Large Scale Residential Development Area Project” CEQR No. 17DCP148M. October 29, 2018 INTRODUCTION This submission is filed on behalf of the Lower East Side Organized Neighbors (“LESON”)1, the Chinese Staff & Workers’ Association (“CSWA”)2, National Mobilization Against Sweatshops (“NMASS”)3, and Youth Against Displacement (“YAD”)4—groups of activists and 1 The Lower East Side Organized Neighbors (LESON) is a group made up of concerned residents of the Lower East Side and its surrounding areas, including Antonio Queylin of 82 Rutgers Slip apt. 22J NY, NY 10002. These residents have joined together to challenge projects, policies, and other issues which they believe adversely impact the current and future preservation of their community. 2 The Chinese Staff & Workers’ Association (CSWA) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan workers' rights organization based in New York City, with its primary office in the Lower East Side. CSWA primarily assists workers in restaurants, the garment industry, and construction industries; however it is active among workers in a variety of professions. Many of its over 2,000 worker members reside in, or work in, the Lower East Side. 3 Founded in 1996, National Mobilization Against Sweatshops (NMASS) is a workers membership organization that was started by young working people in New York City. -

Penn Station Table of Contents

www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org Penn Station Table of Contents Slide/s Part Description 1N/ATitle 2 N/A Table of Contents 3~88 1 An Absolute Necessity 89~268 2 The Art of Transportation 269~330 3 Eve of Destruction 331~368 4 Lost Cause 369~417 5 View to a Kill 418~457 6 Men’s Room Modern 458~555 7 Greatness to Come Fall From Grace 1 2 Part 1 The Logical Result An Absolute Necessity 3 4 “…The idea of tunneling under the Hudson and East Rivers for an entrance into New York City did not evolve suddenly. It was the logical result of long-studied plans in which Mr. Alexander Johnston Cassatt, the late President of the Company, participated from the beginning, and an entrance into New York City was decided upon only when the Executive Officers and Directors of the Company realized that it had become an absolute necessity…” RE: excerpt from The New York Im- provement and Tunnel Extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad Left: Alexander J. Cassatt (1839-1906), Above: caption: “The empire of the Pennsylvania Railroad, President – Pennsylvania Railroad extending through most of the northeast, but unable to reach Company (1899-1906) 5 Manhattan until 1910” 6 © J.M. Syken 1 www.PDHcenter.com www.PDHonline.org “…After the Company in 1871 leased the United Railroads of New Jersey, which terminate in Jersey City, the Officers of the Railroad looked longingly toward New York City. They wanted a station there, but they were confronted both by the great expense of such an undertaking, as well as the lack of a feasible plan, for at that time the engineering obstacles seemed to be insurmountable.