Tumalo Creek Watershed Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Trail Access and Conditions Update

Summer Trail Access and Conditions Update Updated June 30, 2017 July Fourth Report! Summer Trail Highlights Summer season high use at recreation sites and trails. Fire season in effect. Possessing or discharging of fireworks prohibited on National Forest Lands. Summer trails below 5,800’ elevation are mostly snow free and accessible. Trail clearing (mostly volunteers) in progress on lower/mid elevation trails. Snow lines are rising to 6,000-7-,200 ft. Please avoid using muddy trails. 60-70% of Wilderness trails are blocked by snow! Wilderness permits required. Biking prohibited in Wilderness! Trails near snow lines (approx.6,000-7,000’) are Be aware of weekday (M-F) trail, road likely muddy. Please avoid using muddy trails as and area closures for logging early season use causes erosion and tread damage. operations, south and west of Cascade Higher elevation trails under patchy, sectional to Lks Welcome Station. near solid snow. 70% of PCT under snow. May 15-Sept 15, dog leash requirement in effect on Deschutes River Trails. Northwest Forest Passes required at various trailheads and day use sites. Cascade Lakes Welcome Station and Lava Lands are open 7 days/wk. NW Forest Passes available. Hwy 46 open but June 19-October 31 bridge related construction at Fall Creek and Goose Creek (Sparks Lk area) will have delays. Cultus Lk and Soda Creek campgrounds are closed until further notice. Go prepared with your Ten Essential Trail clearing in progress on snow free trails with Systems. approx. 50-60% of trails are cleared of down trees. Have a safe summer trails season! GENERAL SUMMER TRAIL CONDITIONS AS OF JUNE 30, 2017: Most Deschutes National Forest non-Wilderness summer trails below 6,000’ elevation are snow free and accessible. -

Analysis of Regulated River Flow in the Upper Deschutes Basin Using Varying Instream and Out-Of-Stream Conditions

Upper Deschutes River Basin Study Technical Memorandum Analysis of Regulated River Flow in the Upper Deschutes Basin using Varying Instream and Out-of-Stream Conditions U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region December 2018 Mission Statements U.S. Department of the Interior PROTECTING AMERICA’S GREAT OUTDOORS AND POWERING OUR FUTURE The U.S. Department of the Interior protects America’s natural resources and heritage, honors our cultures and tribal communities, and supplies the energy to power our future. Bureau of Reclamation The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. CONTENTS 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Goals of Study ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Water Resources Modeling Process ............................................................................ 1 2. Reference RiverWare Model ............................................................................................. 3 2.1. Irrigation Demand Pattern ............................................................................................ 8 2.2. Upper Deschutes River Operation ..............................................................................10 2.2.1. Crane Prairie ..................................................................................................11 -

Regon Lyfisher C O C O FF

The entral regon lyfisher C O C O FF www.coflyfishers.org An Active Member Club Volume 28 Number 8 August 2005 COF GOLD LAKE MAUPIN N. F. MALHEUR PICNIC OUTING OUTING BULL TROUT Thursday LOWER SPAWNING th August 18th September 10 DESCHUTES SURVEY 6:30 PM 9:00 AM August 30-31 September 15-18 Aspen Hall Shevlin Park Gold Lake Boat Ramp Beaver Tail or Mack’s Crane Prairie Guard Bend Parking Area Canyon Campground Station - SPECIAL NOTICE – As is our practice every year, there WILL NOT be a regular meeting at the Senior Center this month. Instead, please join us at the annual COF picnic on Thursday, August 18 at Aspen Hall in Shevlin Park, 6:30PM. Random Casts River access rights and ground water pumping continue to be a “hot button” issue in the State and Central Oregon. One proposed piece of legislation was stopped in committee that would have guaranteed a piece-meal approach to river management. There would have been different rules throughout the State, and rules could change in different reaches of a river. The conflict for river rights would have continued with a convoluted management process that could diminish access over time. The maintenance of this right is important to any river user, but we must recognize this right comes with responsibilities and demands respect for the adjacent land owners. The high water mark is only a boundary, and we must leave the banks clear of debris and trash. DO NOT venture on to other people’s property. In a quick few days, the legislature passed a law to circumvent a recent court ruling that had limited ground water pumping in the Upper Deschutes basin. -

Deschutes National Forest

Deschutes National Forest Summer Trail Access and Conditions Update KNOW BEFORE YOU GO! Updated July 10, 2015 Summer Trail Highlights Fire danger is extreme and Public Use Restrictions on campfires, wood burning, BBQ, smoking, and chainsaw use begin 7-10 at 00:01. Summer trails are now snow free with most trails either cleared of downed trees or light to moderate. Expect downed trees on several trails. July 11/12, bike race out of Wanoga Sno-Park with possibly 250 riders. Tumalo Falls Road/Trailhead, all trails into TH and all access to the Falls and viewpoints now closed to all vehicle, foot and bike traffic until further notice. Pipeline construction in YCC crews help improve “defensible space” around Shooting Star Nordic Shelter by removing excess brush and trees progress thru the area. surrounding the shelter. 5/15-9/15 dogs on leash only on Deschutes River Trails. 7/15 – 9/15 dogs on leash only on several high use Wilderness trails. Hwy 46 (Cascade Lks Hwy), Road 21 into Newberry/ Paulina Peak Road, Road 16 to Three Creeks area and Hwy 242 open for the season. Road 370 beyond Todd Lk on or before 7/11; vehicles on open roadways only. Go prepared with your Ten Essential Systems: Navigation (map and compass) Sun protection (sunglasses/sunscreen) Insulation (extra clothing) Illumination (headlamp/flashlight) Volunteers are hitting their stride with trail clearing. Approx. 70% of Deschutes NF trails are now cleared of First-aid supplies down trees. Thank you volunteers and trail crew! Fire(waterproofmatches/lighter/candles) Repair kit and tools Nutrition (extra food) Hydration (extra water) Emergency shelter GENERAL SUMMER TRAIL CONDITIONS AS OF JULY 10: HOT, dry and mostly sunny weather has created dusty trails, dry creeks, lowered lake levels and elevated fire danger. -

Summer Trail Access and Condition Update October 29Th – November 12Th, 2020

z Summer Trail Access and Condition Update October 29th – November 12th, 2020 Autumn Trail Highlights • Nearly all fire associated trail closures have been LIFTED on the Deschutes National Forest. An area closure remains on the Green Ridge Trail. • There is a temporary closure on the Tumalo Creek trail, due to bridge construction. The closure is just east of the junction with South Fork Trail. See inside for more info. • Recent wind storms have brought down trees on many area trails. Visitors should anticipate them on the trail, as removal efforts will be limited. The reports below represent the best of our knowledge at the time it was written. • Forest Road 370 is closing for the season on Tuesday, November 3rd. • Motorized bicycles (E-Bikes) and motorized skateboards (“One Wheels” ) are not allowed on non-motorized trails. • When on the trail, please treat fellow trail users with courtesy. Volunteers with the Central Oregon Recent photo of a volunteer removing Nordic Club and Central Oregon Trails windfall on the Mirror Lakes Trail, Three Alliance, along with FS staff, remove an Sisters Wilderness. Many trails still have old bridge on the Tumalo Creek Bridge. moderate to heavy downfall on them. A new bridge is currently being constructed. DESCHUTES NATIONAL FOREST SUMMER TRAIL CONDITIONS AS OF 10/29/20: **Conditions subject to change without notice and at whim of nature.** Bend/Fort Rock Ranger District ❖ Phil’s Area Trails – All trails are clear and riding well. E-Bikes are NOT allowed on any non-motorized trails. For more information on COTA, go to: http://cotamtb.com/ ❖ Tumalo Falls Area – Road to trailhead open for summer season. -

Shevlin Park Rd

ắằẳ Tumalo State Park (Day Use Area) BEND Juniper Ridge Sky View COOLEY Middle School Lava Ridge URBAN TRAIL Elementary School 20 97 Rock Ridge Cascade Park Village Shopping SYSTEM Center (Gopher Gulch: Future Park - RD. DESCHUTES MKT. Harvest No Public Access) Boyd O.B. RILEY RD. Park Ponderosa Park Elementary YEOMAN RD. D Lava Ridges ắ Pine Nursery Archie Briggs Deschutes EMPIRE AVE. Natural Area Park KIRKALDY CT. River Trail PUTNAM RD. (NO PUBLIC Canyon PARKING) Sawyer Park Sawyer 3RD ST. Uplands Park ắằ JOHNSON RD. Aspen Hall ắ Archie BriggsCanyon Trail Pilot Butte Mirada Park ắ Canal Trail ẳ BEND BEND PARKWAY SHEVLIN PARK RD. S EE SHEVLIN ằ RIVER BLVD. PURCELL RIVER’S PROMENADE EDGE Awbrey GOLF Canal ắ COURSE Sylvan Park Village Row Park PARK INSET ẳ Park Shevlin Park Quail Park BUTLER MARKET RD. Mt. View MT. WASHINGTON DR. High School RD. HAMBY Covered Bridge MT. WASHINGTON DR.COCC & Riverview OSU Cascades Campus Summit Park Park Stover Park SUMMIT DR. Ensworth Buckingham Hollinshead Elementary Elementary River Trail 27TH ST. Deschutes Orchard Park Hillside I Mt. View Park Park First St. Park ắ D D Rapids Big Sky 3RD ST. Al Moody D Hillside II Park Park St. Charles Park Park ắ Pioneer Medical Center ắ Discovery Lewis & NEFF RD. Park OLNEY Trail Clark Park PORTLAND ắ Pilot Butte Fremont Juniper Middle Meadows Elementary School ắằ NW 12TH. Marshall NEWPORT Pacific High School High Lakes Highland Brooks Elementary School Park 9TH ST. Providence Park Sunset School Park Westside GREENWOOD View Park Village Harmon To Tumalo Compass School Juniper Swim & Pilot Butte Park Park Drake Fitness Center Pilot Butte Park State Park ắ Juniper State Park ắằẳ GALVESTON Park Park Summit Amity Creek Old Bend ắ Miller High School School Gym Elementary Overturf FRANKLIN AVE. -

Deschutes National Forest Summer Trails Below 4,400’ Elevation Are Snow Free and Accessible

Spring Trail Access and Conditions Update Updated April 27, 2017 Spring Trail Highlights Most summer trails below 4,500’ elevation are snow free and accessible. Snow lines are slowly rising! Please avoid using muddy trails. Trailheads and summer trails above 4,500’ are mostly blocked by snow and late winter-like conditions. Snow free access to higher elevation trails likely to be delayed until late July to late August, due to snow and down trees. Be aware of weekday (M-F) trail, road and area closures for logging operations, north and west of Cascade Lks Welcome Station and Deschutes River trails from Lava Island to Aspen. Trails near snow lines (approx.4,500-5,000’’) are Northwest Forest Passes required at likely muddy. Please avoid using muddy trails as early season use causes erosion and tread damage various trailheads and day use sites beginning May 1. Cascade Lakes Welcome Station now open Saturdays/Sundays, 10-4. Lava Lands will be open Thurs-Mon. starting May 5. Most Deschutes NF snow parks now lack adequate snow for fair to good winter trail access. Winter trail grooming is finished for the season. Seasonal closures of Hwy 46, Hwy 242, Road 21, Road 16, Tumalo Falls Rd and Road 370 are still in effect until further notice. Spring road plowing in Various signing at snow parks is in place to help make progress on some key access roads. parking/traffic flow safer and more efficient. Please follow posted traffic and other snow park signage. Watch weather forecasts closely. Go prepared with your Ten Essential Systems. -

Healthy Tumalo Community Plan

HEALTHY TUMALO COMMUNITY PLAN A Health Impact Assessment on the Tumalo Community Plan A Chapter Of The 20‐Year Deschutes County Comprehensive Plan Update CONTRIBUTORS This project was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials through a grant administered by the Oregon Health Authority, Office of Environmental Public Health. Deschutes County HIA Workgroup: Coordination, Literature Review, Analysis • Therese Madrigal, Deschutes County Health Services • Kate Wells, St. Charles Health System • Kim Curley, Commute Options for Central Oregon Advisory Committee • Nick LeLack, Planning Director, Deschutes County Community Development • Terri Hansen Payne, Sr. Planner, Deschutes County Community Development • Peter Russell, Sr. Transportation Planner, Deschutes County Community Development • Susan Peithman, Oregon Advocate for Bicycle Transportation Alliance • Carolyn Perry, Tumalo Resident • Paula Kinzer, Tumalo Resident • Jessica Kelly, Tumalo Resident • Barbara Denzler, Environmental Health Consultant TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary 1 II. Introduction 4 a. HIA Rationale III. Community Profile 5 a. Greater Tumalo Area b. Vulnerable Populations c. How the West Was Won Back: A Visioning Exercise IV. HIA Methodology 10 a. Guiding Principles b. HIA Components c. Screening d. Community Participation e. Scoping V. Literature Review and Local Conditions 13 a. Physical Activity b. Traffic Safety c. Rural Livability VI. Conclusion: Health Impacts of Tumalo Community Plan Policies 19 a. Hwy 20 i. HIA Workgroup Recommendations b. Multi‐modal Trail System & Recreational Amenities i. HIA Workgroup Recommendations VII. Appendices a. Literature Review and Data by Policy Focus Area b. Bend Metro Parks and Recreation District Letter to Deschutes County Planning c. Tumalo Community Plan Original and Post‐HIA Draft d. -

2020 October Homesteader

Music is Medicine Redmond New to the collection, a Roadrunners piece of harmonious history Turn 60 See p. 4 We honor this elite team of heroes See p. 5 The Homesteader Deschutes County Historical Society Newsletter—October 2020 Shevlin Park Timeline 1929 – The Tumalo Hatchery closes due to continual freezing problems on Tumalo Creek. In accordance with the 1919 deed’s restrictions of the hatchery parcel, the 13.5 acre property reverted to Shevlin Hixon which in turn deeded it to the City of Bend to be added to the park. This brought the Park’s total acreage to 388. 1930 – The Skyliners Ski Club builds Shevlin Park a 225’ X 125’ skating rink at the hatchery. Centennial 1941 – Brooks-Scanlon builds a Above: Skaters at the old Hatchery building; Inset: Present day Aspen Hall railroad trestle over the park to access their timberlands to the west This is where you go to get away from it all. To walk, run and bike. and north. To picnic, read and reflect. To watch birds and deer and lizards and 1950 – Brooks-Scanlon buys out Shevlin-Hixon. The Shevlin-Hixon ponderous trees and a quicksilver creek. To listen to the wind, the sawmill was closed at the end of creek, the voice of your friend, your partner, yourself. To teach your 1950. kids to fish, skip stones and explore the wilds, carefree and 1950s – The Hatchery building has fallen into disrepair. In the late completely unplugged. 1950s Vince Genna, the city’s This is Shevlin Park. It is the crown jewel of The Bend Park and assistant recreation manager, expresses a desire to restore the Recreation District and only four miles west of the hustle and bustle building for use as a community of downtown Bend. -

Upper Deschutes Subbasin Assessment August 2003

Upper Deschutes Subbasin Assessment August 2003 By Kolleen E. Yake EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Upper Deschutes Subbasin Assessment began work in 2002 as a project of the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council. From its inception, the assessment has been a cooperative venture with multiple partners, participants, and advisors. Funding for the project came from grants received from the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. In-kind donations of time, technical assistance, contract services, and equipment were generously contributed to the project by the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, Deschutes National Forest, the Deschutes Resources Conservancy, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Bureau of Land Management, OSU-Cascades, the Nature Conservancy, the Oregon Water Resources Department, Deschutes County Soil and Water Conservation District, and GeoSpatial Solutions among many others. The purpose of the Upper Deschutes Subbasin Assessment was to gather together existing data and information on all the historic and current conditions that play a role in impacting the watershed health of the subbasin. The details, recommendations, and data gaps discussed within the assessment will assist the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council and other natural resource managers in the area identify key restoration projects and opportunities to enhance fish and wildlife habitat and water quality in the subbasin. By combining all of the existing available information on watershed resources, the Upper Deschutes Watershed Council hopes to raise community awareness about the interconnections and impacts within the whole Upper Deschutes Subbasin system. The key findings and recommendations within the assessment identify and prioritize opportunities for voluntary actions that are directed toward improving fish and wildlife habitat and water quality. -

Central Oregon Interior Redband Genetic Status Project

Central Oregon Interior Redband Genetic Status Project State(s): Oregon Managing Agency/Organization: USDA Forest Service – Deschutes National Forest Type of Organization: Government Project Status: Underway Project type: WNTI Project Project action(s): Assessment Trout species benefitted: Interior Redband Trout Population: Tumalo Creek Watershed and South Fork Crooked River Watershed Project summary: The project would determine the genetic status of Interior Columbia River Basin Redband Trout populations in Central Oregon within the Tumalo Creek and South Fork Crooked River watersheds, where rainbow trout of hatchery origin have been liberally stocked in the past. Determining the status is critically important to fishery managers with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for the management and conservation of this species, which are classified as a sensitive species with the Forest Service, BLM, and the State of Oregon. Future and ongoing land management practices in these watersheds could potentially impact water quality and Redband Trout habitat. An ongoing project within the Tumalo Creek watershed, located approximately 15 miles west of Bend on national forest lands, is the diversion of headwater springs to supply the City with municipal water, which affects streamflow in both Bridge and Tumalo Creek. Populations of either native Redband Trout or hatchery- origin rainbow trout exist above Tumalo Falls on Tumalo Creek, which is a vertical 97 foot high migrational barrier. A possible scenario is that streamflow that would naturally flow from the springs into Redband- occupied habitat of Tumalo Creek is instead being diverted into Bridge Creek that is considered void of fish upstream of the municipal water intake. -

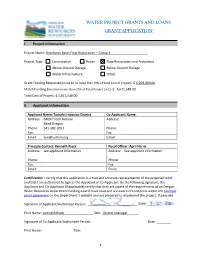

Grant Application

WATER PROJECT GRANTS AND LOANS GRANT APPLICATION I. Project Information Project Name: Deschutes Basin Flow Restoration – Group 3 Project Type: Conservation Reuse Flow Restoration and Protection Above-Ground Storage Below-Ground Storage Water Infrastructure Other: Grant Funding Requested (must be no more than 75% of Total Cost of Project): $ 1,200,000.00 Match Funding (must be no less than 25% of Total Project Cost): $ 4,671,548.00 Total Cost of Project: $ 5,871,548.00 II. Applicant Information Applicant Name: Tumalo Irrigation District Co-Applicant Name: Address: 64697 Cook Avenue Address: Bend Oregon Phone: 541-382-3053 Phone: Fax: Fax: Email: [email protected] Email: Principle Contact: Kenneth Rieck Fiscal Officer: April Harris Address: see applicant information Address: See applicant information Phone: Phone: Fax: Fax: Email: Email: Certification: I certify that this application is a true and accurate representation of the proposed work and that I am authorized to sign as the Applicant or Co-Applicant. By the following signature, the Applicant and Co-Applicant (if applicable) certify that they are aware of the requirements of an Oregon Water Resources Department funding award, have read and are aware of conditions within the example grant agreement on the Department’s website and are prepared to implement the project, if awarded. Signature of Applicant/Authorized Person: _____________________________ Date: ________ Print Name: Kenneth Rieck Title: District Manager Signature of Co-Applicant/Authorized Person: Date: ________ Print Name: