Fully to Appreciate the Antiquarian Lore of the Place Without First Comprehending the Traditions Which Lie Nearest the Heart of the People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rrsq Wzrwfiftq{Rqftre

rrsqwzrwfiftq{rqftre NationalCouncil for TeacherEducation (AStatutory Body of theGovernment of lndia)- (qr{d{r<rR i5r q6' Ae-€ €sri) SoutheinRegional Committee qQurqHq qnR $?I€g5-dcr em NCTE F.SRO/NCTE/ApS09669/8.Ed/Ap/201 6814s- Date:\O TO BE PUBLISHEDIN GAZETTEOF INDIAPART III SEGTION 4 CORRIGENDUM With referenceto this officeorder No. F.SRO/APSO9669lB.EdlAP12Q15164506dated13.05.2015 wherein a revised recognitionorder was issuedto PalnaduCollege of Education,Sy No. 158/94, 158/1081,1SBI1'|B, 1Sgt12B, Narayanapuram,Dachepalli Village, Guntur District-522414,Andhra Pradesh the followinqcorriqendum is Sl.No. INSTEADOF WORDS MAY BE READ AS Page 1 AND WHEREAS,the institutionPalnadu Cottege AND WHEREAS,the institutionPalnadu Cottege of -2 Para of Education, Sy No. 158/9A, 158/10B1, Education, Sy No. '158/9A,158/1081, 158/118, '158112B, 15An1B, 1581128,Narayanapuram, Dachepa i Narayanapuram, Dachepalli liltage, Village, Guntur District522414, A,ndhra Guntur District-522414,Andhra Pradesh has by Pradesh has by affidavit consentedto come affidavitconsented to come underNew Regulationi underNew Regulationsand soughtfor two basic andsought for one basicunit in B.Ed. unitsin B.Ed.,which require additional facilities Page 1 I AND WHEREAS,it has been decided to permit AND WHEREAS,it has beendecided to permitthe Para 4 I institutionto have two basic units of 50 studentsei institutionto haveone basicunit of 50 studentseach i suhjecitc th: inoti:ut:cirfuif;l:ing f,.rI-J*i;g cci.:d:ii I namety, namery, I | (D. The institutionshall submit revalidated FDRS (i). The institutionshall submitrevalidated FDRS of I of the enhancedvalues, in jointaccount with the enhancedvalues, in joint accountwith the I the SRC before30 June,2015 faitingwhich SRC before 30 June, 2015 failing which the I the recognitionwill be withdrawn. -

114Th-SEAC AP 6-8 March-2018

114th SEAC A.P. List of Applications to be placed in 114th SEAC,A.P. Meeting to be held on 06.04.2018,07.04.2018 and 08.04.2018 at 10:00 AM at A.P. Pollution Control Board, Zonal Office, Beside RTA Office, Madhavadhara, VUDA Layout, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh. Line of S.No Date Proposal No Industry Name District Activity 06.04.2018 10.00 A.M. ( 1 to 18) 1 21.02.2018 SIA/AP/MIN/73119/2018 7.852 Ha Colour Granite Mine of K.Srikar Reddy, Colour Granite Sy.No.650/P, Valasapalli (V), Madanapalli (M), Chittoor Mine Chittoor District (CTR) 2 21.02.2018 SIA/AP/MIN/73120/2018 5.117 Ha Colour Granite Mine of Smt.K.Shalini, Colour Granite Sy.No.650/P, Valasapalli (V), Madanapalli (M), Chittoor Mine Chittoor District (CTR) 3 01.03.2018 SIA/AP/MIN/73043/2018 10.0 Ha Colour Granite Mine of M/s.Karthika Mines & Colour Granite Minerals Pvt.Ltd. at Sy. No. 763/P, Jogannapeta village, Mine Ananthapur Nallacheruvu Mandal, Ananthapur District, Andhra (ANT) Pradesh 4 01.03.2018 SIA/AP/MIN/73275/2018 9.340 Ha Quartzite Mine of Sri. Paila Gouri Sankara Quartzite Rao Mining at Sy.No: 1, Guruvinaidupeta Village, Vizianagaram Pachipenta Mandal, Vizianagaram District, Andhra (VZM) Pradesh. 5 07.03.2018 SIA/AP/MIN/72654/2018 15.00 Ha Colour Granite Mine of M/s. Kasturi Granites & Colour Granite Srikakulam Exports at Sy. No. 13, Palavalasa Village, Bhamini Mine (SKM) Mandal, Srikakulam District, Andhra Pradesh 6 07.03.2018 SIA/AP/MIN/73372/2018 3.960 ha. -

National Movement

Factors for the rise of Nationalism in Andhra • Economic Problems – Land Revenue, Taxes, Famines, Lack of agriculture Development. • Western Education, Macaulay Minute. • Social Reforms, Veereshalingam and Raghupathi Venkata Ratnam Naidu. • Press and Journalism, Krishna Patrika, Andhra Patrika. • Middle Classes and Early Political Associations. • Madras Native Associations, Madras Mahajana Sabha, Kakinada Literary Society. Three Phases of Indian Nationalism, 1885-1947 • Moderates 1885-1905 – Causes, Political, Economic, Social and Constitutional Demands • Methods – Petition, Prayer, Deputation. • Leaders – Ananda Charyulu, N. Subba Rao, Gutti Kesava Pillai, P. Rangaiah Naidu, A.P., Parthasarathi Naidu – District Associations. • Rise of extremism-New Political Developments in Japan, Russia, Ireland, Partition of Bengal. • Policies of Lord Curzen – Reaction all over India Lal-Bal-Pal. Ganesh, Shivaji Festivals. Visits by Leaders • Visit of Bipan Chandra Pal to Andhra 1907. • Mutnuri Krishna Rao visit to Visakhapatnam – Rajahmundry – Balabharathi Samaj: Vijayawada – Raja of Munagala Gurt – Machilipatnam. • Political activity in Andhra. Ideas of Swadeshi Swaraj, Boycott, National Education. • Andhra National Education Committee at Rajahmundry. • Machilipatnam – Foundation of National College – Andhra Jateeya Kalasala. • Impact of Pal’s visit Political awakening – Nationalist consciousness.Chilakamarti-Andhra Milton –Famous song Bharatakhandambu oka padi aavu- • Rajahmundry College 24th April 1907 – Mark Hunter, G. Sarvotham Rao, Vandemataram Badges, Medals – Slogans – Students participation – suspension from college. He was expelled – became active. • Kakinada Riot Case – Captain Kemp. • Kotappakonda Case – Chinnappa Reddy. • Tenali Bomb Case. • Terrorist Bengal Connection Dargi Chanchaiah Gadipathy. • Home Rule Movement – 1916. • Minto-Merley Reforms 1909 – Tilak – Annie Besant Common Weal, New India, Tour of Andhra – She visited Madanapalli and established National College in 1916 with J.H. Cousins as Principal. -

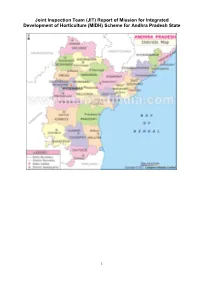

(JIT) Report of Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (MIDH) Scheme for Andhra Pradesh State

Joint Inspection Team (JIT) Report of Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (MIDH) Scheme for Andhra Pradesh State 1 INDEX Sl.No Topic Page No. 1. General Observation of JIT 3 2 Field Visits (i) Visit to West Godavari District 4 (ii) Visit to Guntur District 18 (iii) Visit to Parkasham District 23 Team members:- 1. Dr. H.V.L. Bathla, Chief Consultant (MIDH), DAC, MOA, GOI, New Delhi 2. Dr. G Chandra Mouli, P. I. PFDC, Department of Agri. Engineering, ANG Ranga Agri. University, Hyderabad 3. Sh. B S Subbarayudu, DDH (AEZ), SHM, Andhra Pradesh Representative. Dates of Visit:- 23.06.2014 to 27.06.2014 2 General Observations: 1. In Guntur district T C Banana clusters of 72 ha. having robust growth was observed. The area is prone to cyclones and high winds, with close to 20% of the plants affected on account of above. To minimize damage on account of wind-fall etc., support for each plant is required with Bamboo or other stacking material. Similar condition was observed in West Godavari district also. 2. Canopy management of acid lime in a cluster of 100 acres of 50 farmers in Guntur district has helped the farmers in getting healthy plants as well as better yield. 3. In case of poly houses one entry gate is being used for entering the facility. It would be useful to consider having two gates to avoid any attack of pests and diseases, with only one gate open at any point of time. 4. There is a need to demonstrate the process of rejuvenation for Mango crop to the beneficiaries by the concerned district/block officers in Parkasham district. -

Handbook of Statistics Guntur District 2015 Andhra Pradesh.Pdf

Sri. Kantilal Dande, I.A.S., District Collector & Magistrate, Guntur. PREFACE I am glad that the Hand Book of Statistics of Guntur District for the year 2014-15 is being released. In view of the rapid socio-economic development and progress being made at macro and micro levels the need for maintaining a Basic Information System and statistical infrastructure is very much essential. As such the present Hand Book gives the statistics on various aspects of socio-economic development under various sectors in the District. I hope this book will serve as a useful source of information for the Public, Administrators, Planners, Bankers, NGOs, Development Agencies and Research scholars for information and implementation of various developmental programmes, projects & schemes in the district. The data incorporated in this book has been collected from various Central / State Government Departments, Public Sector undertakings, Corporations and other agencies. I express my deep gratitude to all the officers of the concerned agencies in furnishing the data for this publication. I appreciate the efforts made by Chief Planning Officer and his staff for the excellent work done by them in bringing out this publication. Any suggestion for further improvement of this publication is most welcome. GUNTUR DISTRICT COLLECTOR Date: - 01-2016 GUNTUR DISTRICT HAND BOOK OF STATISTICS – 2015 CONTENTS Table No. ItemPage No. A. Salient Features of the District (1 to 2) i - ii A-1 Places of Tourist Importance iii B. Comparision of the District with the State 2012-13 iv-viii C. Administrative Divisions in the District – 2014 ix C-1 Municipal Information in the District-2014-15 x D. -

(Nredcap) Tadepalli Status of Renewable Energy Power

NEW AND RENEWABLE ENERGY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION OF AP LTD (NREDCAP) TADEPALLI STATUS OF RENEWABLE ENERGY POWER PROJECTS COMMISSIONED IN ANDHRA PRADESH STATE AS ON 30.09.2020 Resource Cumulative capacity Capacity Cumulative commissioned up to commissioned capacity 2019-20 during 2020-21 commissioned (in MW) (in MW) (in MW) Wind Power 4079.37 - 4079.37 Solar Power 3521.99 13.75 3535.74 Small Hydro 102.598 - 102.598 Biomass Based 171.25 - 171.25 Biomass Energy Co-generation 65.45 - 65.45 (Non-Bagasse) (Captive use only) Co-Generation with Bagasse 206.95 - 206.95 Municipal Solid Waste 6.15 - 6.15 Industrial waste 40.01 - 40.01 TOTAL 8193.768 13.75 8207.518 NREDCAP LIST OF WIND POWER PROJECTS COMMISSIONED Installed Name & Address of the Financial Date of S.No Location District capacity company year Commissioning in M.W 1 A.P. GENCO Wind Farm Ramagiri Ananthapuramu 1994-95 Nov’ 94 2.00 2 NEDCAP WIND FARM Kondamedapally Ananthapuramu 2000-01 31.03.2001 2.75 3 NEDCAP Wind FARM Narasimahakonda Nellore 2004-05 07.05.2004 2.50 4 The Andhra Sugars Limited, Ramagiri, Ananthapuramu 1994-95 30.9.94 2.025 5 Deccan Cements Ltd, Ramagiri Ananthapuramu 1994-95 26.02.95 0.90 6 Deccan Cements Ltd, Ramagiri Ananthapuramu 1995-96 30.09.95 0.675 7 ITW Signode Limited, Ramagiri Ananthapuramu 1995-96 25.05.95 1.00 Navabharat Industrial Linings 8 Ramagiri Ananthapuramu 1995-96 30.08.95 2.00 & Equipment Limited (NILE) Renewable Energy Systems 9 Ramagiri, Ananthapuramu 1995-96 26.09.95 3.00 Ltd, 10 Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd Ramagiri Ananthapuramu 1995-96 13.09.95 3.00 Nagarjuna Construction 11 Ramagiri Ananthapuramu 1995-96 30.09.95 3.00 Co.Ltd, A.P.S.Road Transport Corprn. -

Rani Rudrama Devi.Pdf

ISBN 978-81-237-7817-4 First Edition 2016 (Saka 1937) © Alekhya Punjala 2016 Rani Rudrama Devi (English) ` 145.00 Published by the Director National Book Trust, India Nehru Bhawan 5 Institutional Area, Phase-II Vasant Kunj, New Delhi - 110070 Website: www.nbtindia.gov.in CONTENTS Preface vii 1. History of the Kakatiyas 1 2. Reign of Rudrama Devi 15 3. Rani Rudrama Devi’s Persona 51 4. Patronage of Literature, Art, Architecture and Culture 55 Annexures Annexure I: Some Important Inscriptions from the Kakatiya Period 101 Annexure II: Chronology of the Kakatiya Dynasty 107 Bibliography 109 PREFACE Merely a couple of days ago, while going through the nomination process for Presidency, Hillary Clinton made a telling comment that she really didn’t know whether America was ready for a woman President. It is a matter of great pride that India has shown itself to be a path-breaker on this count. In mythology as well as since historical times we have worshipped goddesses and attributed the most important portfolios to them. Historically it was Rani Lakshmi Bai of Jhansi who sowed the first seeds of rebellion towards almost a century long battle for the freedom of India. Our history is replete with stories of many such brave women who have walked the untrodden path. Lives of Nagamma the leader of Palanati Seema, Brahma Naidu’s mother Seelamma, Tribal king Yerukalaraju’s mother vii Rani Rudrama Devi Women Pioneers Kuntala Devi, Erramma Kanasanamma, the lady who contributed to resurrection of the Kakatiya clan, the valorous Gond Queen Rani Durgavati 1524-1564 AD, the Muslim woman warrior Chand Bibi 1550-1599 AD, great ruler and Queen of the Malwa kingdom Devi Ahilyabai Holker 1725-1795 AD and the first and only woman ruler to sit on the throne of Delhi Sultanate Razia Sultan 1236 AD, are women who have excelled in every aspect of their lives and inspired us. -

BPCL Appointment of Retail Outlet Dealerships in the State of Andhra Pradesh by BPCL

LOCATION LIST - BPCL Appointment of Retail Outlet Dealerships in the State of Andhra Pradesh By BPCL Estimated Minimum Dimension (in M) / Area of Finanace to be arranged by Fixed Fee / Min Security type of Mode of Sl. No Name Of Location Revenue District Type of RO monthly Sales Category site (in Sq M)* (Frontage x applicant 9a working capital, bid amount (Rs Deposit (Rs Site* selection Potential # Depth = Area) 9b infra capital in Lakhs) in Lakhs) 1 2 34 5 6 7 8a 8b 8c 9a 9b 10 11 12 SC/SC CC 1/SC Estimated Estimated PH/ST/ST fund required working CC 1/ST for capital Draw of Regular / PH/OBC/OB CC/ DC development MS+HSD in Kls Frontage Depth Area requirement Lots / Rural C CC 1/OBC /CFS of for operation Bidding PH/OPEN/O infrastructure of RO (Rs in PEN CC at RO (Rs in Lakhs) 1/OPEN CC Lakhs ) 2/OPEN PH ON SANAPA TO ALAMUR ROAD WITHIN 1KM FROM SANAPA Draw of 1 HIGH SCHOOL ANANTAPUR RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 2 Thumuluru Village, Kollipara mandal GUNTUR RURAL 85 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 3 Nagaram Village, Nagaram Mandal GUNTUR RURAL 85 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 4 Mothugudem on Mothugudem - Donkarayi Road EAST GODAVARI RURAL 60 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 5 Darbharevu village, Narsapur Mandal WEST GODAVARI RURAL 95 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 6 NAVUDUR (MARTERU TO VEERAVASARAM R&B ROAD) WEST GODAVARI RURAL 133 SC CFS 30 25 750 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 7 In Nuleveedu village, Galiveedu mandal. -

Total 2553.35 3499.404 6052.754

NEW AND RENEWABLE ENERGY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION OF AP LTD (NREDCAP), HYDERABAD STATUS OF RENEWABLE ENERGY POWER PROJECTS COMMISSIONED IN ANDHRA PRADESH STATE AS ON 31.03.2017 Resource Cumulative Capacity Cumulative capacity commissioned capacity commissioned during 2016-17 commissioned up to 2015-16 (in MW) (in MW) (in MW) Wind Power 1416.32 2187.45 3603.77 Solar Power ( GOI ) 92.392 1106.034 1198.426 Solar Power ( State Policy ) 486.80 195.15 681.95 Small Hydro 89.098 - 89.098 Biomass Based 171.25 - 171.25 Biomass Energy Co-generation (Non-Bagasse) (Captive use 50.38 4.77 55.15 only) Co-Generation with Bagasse 206.95 - 206.95 Municipal Solid Waste 6.15 - 6.15 Industrial waste 34.01 6.00 40.01 TOTAL 2553.35 3499.404 6052.754 NREDCAP, HYDERABAD LIST OF COMMISSIONED WIND POWER PROJECTS IN ANDHRA PRADESH STATE Date of Installed S.N Name & Address of the Financia Location District Commission capacity o company l year ing in M.W I.1 A.P. GENCO Wind Farm Ramagiri Anathapuramu 1994-95 Nov’ 94 2.00 2 NEDCAP WIND FARM Kondamedapally Anathapuramu 2000-01 31.03.2001 2.75 3 NEDCAP Wind FARM Narasimahakonda Nellore 2004-05 07.05.2004 2.50 II.1 The Andhra Sugars Limited, Ramagiri, Anathapuramu 1994-95 30.9.94 2.025 1 Deccan Cements Ltd, Ramagiri Anathapuramu 1994-95 26.02.95 0.90 2 Deccan Cements Ltd, Ramagiri Anathapuramu 1995-96 30.09.95 0.675 3 ITW Signode Limited, Ramagiri Anathapuramu 1995-96 25.05.95 1.00 Navabharat Industrial 4 Linings & Equipment Ramagiri Anathapuramu 1995-96 30.08.95 2.00 Limited (NILE) Renewable Energy Systems 5 Ramagiri, Anathapuramu 1995-96 26.09.95 3.00 Ltd, 6 Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd Ramagiri Anathapuramu 1995-96 13.09.95 3.00 Nagarjuna Construction 7 Ramagiri Anathapuramu 1995-96 30.09.95 3.00 Co.Ltd, A.P.S.Road Transport 8 Ramagiri Anathapuramu 1995-96 30.09.95 5.00 Corprn. -

S.No. Case No. Petitioner Respondent Subject / Prayer 1 2 3 4 O.P.No.41

Schedule of hearings before APERC as on 25-05-2019 PUBLIC HEARING SCHEDULED ON 01-06-2019 (Saturday) at 11.00 AM S.No. Case No. Petitioner Respondent Subject / Prayer 1 Public hearing in the matter of approval of Power Sale Agreement (PSA) signed by APDISCOMs with M/s. NTPC on 11-12-2017 and adoption of tariff under Section 63 of the Electricity Act, 2003 for purchase of 250 MW Solar Power from Kadapa Solar Park under NSM Phase-II, Batch-II, Tranche-I. 2 Public hearing in the matter of approval of Power Sale Agreement (PSA) signed by APDISCOMs with M/s. NTPC and regulation of price under Section 86 (1) (b) of the Electricity Act, 2003 for purchase of power from 750 MW (Phase - II) Solar Park at NP Kunta, Anantapur District. 3 Public hearing in the matter of approval of Power Sale Agreement (PSA) signed by APDISCOMs with M/s. SECI and regulation of price under Section 86 (1) (b) of the Electricity Act, 2003 for purchase of power from 750 MW Kadapa Ultra Mega Solar Park 4 O.P.No.41 of 2019 M/s. Palnadu Solar Power Pvt. Ltd CMD / APSPDCL Petition filed u/s 63 of the Electricity Act, 2003 r/w APERC (Conduct of Business) Regulation 1999 for approval of tariff CE / APPCC / APTRANSCO and for the additional capacity of 4.5 MW of the petitioner’s solar power project as determined through competitive bidding CGM / Projects & IPC / APSPDCL process. HEARING SCHEDULED ON 01-06-2019 (Saturday) at 11.00 AM S.No. -

Guntur District

Guntur District S.No. Name of the Health care facility 1. The Superintendent, Government General Hospital, Guntur. Guntur District. 2. The Medical Officer, Yarlagadda Venkanna Chowdary Oncology Wing & Research Centre, Chinakakani (V), Guntur Rural (M), Guntur District. 3. All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Mangalagiri (V&M), Guntur District 4. The Medical Superintendent, District Hospital, Tenali (V&M), Guntur District 5. The Medical Officer, Community Health Centre , Chilakaluripet (V& M), Guntur District. 6. The Medical Officer, Area Hospital, Bapatla (V&M), Guntur District. 7. The Medical Superintandant, Area Hospital, Narasaraopet (V&M), Guntur District 8. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ), 5/1, Tuffan Nagar, Hanumayya Company Backside, Maruthi Nagar, Guntur, Guntur District 9. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ),Opp: ITC, 60 Feet Road, Behind Water Tank, Srinivasa Rao Thota, Guntur, Guntur District 10. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ), 3rd lane, Anandpet, Guntur, Guntur District. 11. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ),Venugopal Nagar, 8th lane, N.G.O. Colony, Guntur, Guntur District 12. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ), Mangaladas Nagar, 2nd Lane, Guntur Guntur District. 13. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ), Mallikarjunapeta Ratnapuri Colony, Beside Ambedkar Statue, Guntur, Guntur District. 14. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ),Opp: Vijaya Lakshmi Theather, Gundarao Pet, Beside Darga, Nallapadu Road, Guntur, Guntur District. 15. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ), 5/2, IPD Colony, Beside Sai Baba Temple, Ponnur Road, Guntur, Guntur District. 16. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ), L.B. Nagar, Beside Water Tank, Mani Hotel Centre, Guntur, Guntur District 17. Mukhyamantri Arogya Kendram (e -UPHC ), Lanchester Ro ad, Beside Ice Factory, Sangadigunta, Guntur, Guntur District. -

New and Renewable Energy Development Corporation of Ap Ltd (Nredcap), Hyderabad Status of Renewable Energy Power Projects Commis

NEW AND RENEWABLE ENERGY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION OF AP LTD (NREDCAP), HYDERABAD STATUS OF RENEWABLE ENERGY POWER PROJECTS COMMISSIONED IN ANDHRA PRADESH STATE AS ON 31.07.2016 Resource Cumulative Capacity Cumulative capacity commissioned capacity commissioned during 2016-17 commissioned up to 2015-16 (in MW) (in MW) (in MW) Wind Power 1416.32 143.80 1560.12 Solar Power ( GOI ) 92.392 250.608 343.00 Solar Power ( State Policy ) 486.80 106.00 592.80 Small Hydro 89.098 - 89.098 Biomass Based 171.25 - 171.25 Biomass Energy Co-generation (Non-Bagasse) (Captive use 50.37 3.00 53.37 only) Co-Generation with Bagasse 206.95 - 206.95 Municipal Solid Waste 6.15 - 6.15 Industrial waste 34.01 - 34.01 TOTAL 2553.34 503.408 3056.748 NREDCAP, HYDERABAD List of commissioned Wind Power Projects in A P State Installed Name & Address of the Financial Date of S.No Location capacity company year Commissioning in M.W I.1 A.P. GENCO Wind Farm Ramagiri 1994-95 Nov’ 94 2 2 NEDCAP WIND FARM Kondamedapally 2000-01 31.03.2001 2.75 3 NEDCAP Wind FARM Narasimahakonda 2004-05 07.05.2004 2.5 II.1 The Andhra Sugars Limited, Ramagiri, 1994-95 30.9.94 2.025 2 Deccan Cements Ltd, Ramagiri 1994-95 26.02.95 0.9 3 Deccan Cements Ltd, Ramagiri 1995-96 30.09.95 0.675 4 Deccan Cements Ltd, Ramagiri 1995-96 23.03.96 0.45 5 ITW Signode Limited, Ramagiri 1995-96 25.05.95 1 Navabharat Industrial Linings Ramagiri 1995-96 30.08.95 2 6 & Equipment Limited (NILE) Renewable Energy Systems Ramagiri, 1995-96 26.09.95 3 7 Ltd, Anathapur Dt.