In Remembrance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1309 HON. GARY L. ACKERMAN HON. EDOLPHUS TOWNS

June 21, 2005 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1309 the academy.’’ The bill directed the Air Force In 2000, Deborah married her long-time best for raising the Sikh flag and making speeches. to develop a plan to ensure that the academy friend, Alvin Benjamin of Glen Head, New The Movement Against State Repression re- maintains a climate free from coercive reli- York. Alvin is the Owner/President of Ben- ports that over 52,000 Sikhs are political pris- gious intimidation and inappropriate proselyt- jamin Development in Garden City, New York. oners in ‘‘the world’s largest democracy.’’ izing. They currently reside in Glen Head, Manhat- More than a quarter of a million Sikhs have As a Coloradan and a Member of the tan, and Highland Beach, Florida. been murdered, according to figures compiled Armed Services Committee, I have been fol- Since her retirement, Mrs. Benjamin has de- from the Punjab State Magistracy. lowing this matter closely and have noted that voted much of her time to charitable organiza- Sikhs are only one of India’s targets. Other Lt. Gen. John Rosa, the Academy’s super- tions dedicated to improving the lives of chil- minorities such as Christians, Muslims, and intendent, has said that the problem is ‘‘some- dren. She is most actively involved with the others have also been subjected to tyrannical thing that keeps me awake at night,’’ and esti- Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, which is repression. More than 300,000 Christians mated it will take 6 years to fix. dedicated to finding a cure for this rare, but have been killed in Nagaland, and thousands The good news is that several reviews of serious blood disease. -

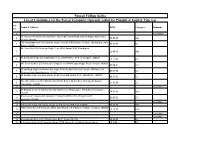

Punjab Vidhan Sabha List of Candidates for the Post of Computer Operator Called for Punjabi & English Type Test

Punjab Vidhan Sabha List of Candidates for the Post of Computer Operator called for Punjabi & English Type test Roll. Name & Address DOB Category Remarks No. 1 Cancelled* Sh. Naveen Bansal S/o Desraj Bansal, B05/01847, Nada Road, Gobind Nagar, Naya Gaon, 2 30.09.92 Gen Mohali. 160103 Ms. Amandeep Kaur D/o Surinder Singh, H.no 58, Vill Dhindsa, PO Kauli, Teh Rajpura, Distt 3 06.07.93 SC Patiala.140701 Sh. Amit Walia S/o Ravinder Singh, H.no 1116, Sector 20-B, Chandigarh. 4 11.08.94 Gen Sh Kulwinder Singh S/o Surjit Singh, H.no 1403-B Sector 37-B, Chandigarh. 160036 5 13.12.92 B.C Ms. Sandeep Kaur D/o Kanwaljeet Singh, H.no 5044/4, Jagjit Nagar, Ropar, Punjab. 140001 6 05.08.97 S.C Sh Sandeep Singh S/o Harmandar Singh, H.no 66, Near Govt Sec. School, Malkana, Teh 7 03.07.89 B.C Talwandi Sabo Distt Bathinda. 151301 Sh Kuldeep Singh S/o Ram Saroop Singh, H.no 686, Sector 29-A, Chandigarh. 160062 8 08.02.87 S.C Ms. Merry D/o Late Sh P Mashi, H.no 315/C, Raipur Khurd, Near Chandigarh Airport. 9 17.03.88 S.C Chandigarh. 160003 10 Cancelled Sh Deepak S/o Sh Vinod Sharma, Mohalla Purian, PO Sujanpur, Teh & Distt Pathankot. 11 24.02.85 Gen 145023 Khushwinder Janjuha S/o Kamaljeet, Vill & PO Bhallari, Teh. Nangal, Disstt 12 20.09.91 S.C Rupnagar.140126 13 Cancelled 14 S.Harpreet Singh S/O S.Chajju Singh, #121B, Sector-30B, Chd. -

The Shiromani Akali Dal and Emerging Ideological Cleavages in Contemporary Sikh Politics in Punjab: Integrative Regionalism Versus Exclusivist Ethnonationalism

143 Jugdep Chima: Ideological Cleavages in Sikh Politics The Shiromani Akali Dal and Emerging Ideological Cleavages in Contemporary Sikh Politics in Punjab: Integrative Regionalism versus Exclusivist Ethnonationalism Jugdep Singh Chima Hiram College, USA ________________________________________________________________ This article describes the emerging ideological cleavages in contemporary Sikh politics, and attempts to answer why the Shiromani Akali Dal has taken a moderate stance on Sikh ethnic issues and in its public discourse in the post-militancy era? I put forward a descriptive argument that rhetorical/ideological cleavages in contemporary Sikh politics in Punjab can be differentiated into two largely contrasting poles. The first is the dominant Akali Dal (Badal) which claims to be the main leadership of the Sikh community, based on its majority in the SGPC and its ability to form coalition majorities in the state assembly in Punjab. The second pole is an array of other, often internally fractionalized, Sikh political and religious organizations, whose claim for community leadership is based on the espousal of aggressive Sikh ethnonationalism and purist religious identity. The “unity” of this second pole within Sikh politics is not organizational, but rather, is an ideological commitment to Sikh ethnonationalism and political opposition to the moderate Shiromani Akali Dal. The result of these two contrasting “poles” is an interesting ethno-political dilemma in which the Akali Dal has pragmatic electoral success in democratic elections -

PUNJAB POLITICS) LESSON NO.1.5 AUTHOR: Dr

M.A. (Political Science) Part II 39 PAPER-VII (OPTION-II) M.A. (Political Science) PART-II PAPER-VII (OPTION-II) Semester-IV (PUNJAB POLITICS) LESSON NO.1.5 AUTHOR: Dr. G. S. BRAR SIKH MILITANT MOVEMENT IN PUNJAB Punjab witnessed a very serious crisis of Sikh militancy during nineteen eighties till a couple of years after the formation of the Congress government in the state in 1992 under the Chief Ministership of late Beant Singh. More than thirty thousand people had lost their lives. The infamous ‘Operation Blue Star’ of 1984 in the Golden Temple, the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards and the subsequent anti-Sikh riots left a sad legacy in the history of the country. The Sikhs, who had contributed to the freedom of the country with their lives, were dubbed as anti-national, and the age-old Hindu-Sikh unity was put on test in this troubled period. The democratic movement in the state comprising mass organizations of peasants, workers, government employees, teachers and students remained completely paralysed during this period. Some found the reason of Sikh militancy in ‘the wrong policies pursued by the central government since independence’ [Rai 1986]. Some others ascribed it to ‘an allegedly slow process of alienation among a section of the Punjab population in the past’ [Kapur 1986]. Still others trace it to ‘the rise of certain personalities committed to fundamentalist stream of thought’ [Joshi 1984:11-32]. The efforts were also made to trace its origin in ‘the socio-economic developments which had ushered in the state since the advent of the Green Revolution’ [Azad 1987:13-40]. -

Bhajan Singh Bhinder

i TABLE OF CONTENTS: Prologue .................................................................................. v What Triggered this Story? .......................................................... vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................... 1 PART 1: MAKING OF A FALSE ICON ................................................. 11 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 12 • What’s in a name? - Shakespeare .................................................... 13 • 7 Books, 2 Authors, 3 Names & 1 Publisher ................................... 21 • Curious case of “Kite Fights”- The 6th book by Pieter ..................... 21 • Donning Multiple Caps: A Christian Missionary? Author? Activist?23 A SIDE STORY: THE MYSTERIOUS PAKISTANI INTELLIGENCE OFFICER..24 CHAPTER 2: BHAJAN SINGH BHINDER .................................................... 25 • Bhinder’s story runs backwards ............................................. 28 • Tales told by Lal Singh .......................................................... 29 • The K-2 conspiracy: Khalistan-Kashmir conspiracy .............. 30 • Lal Singh’s confessions ................................................. 31 • ‘We have been Burnt Before’ ........................................... 32 CHAPTER 3: THE LORD OF DRUGS & OTHER SMALL THINGS ........................ 34 • Capturing Fremont Gurdwara ............................................... 34 • Saffron Express .................................................................... -

Recent Reports Highlight the Continuing Struggle for Sikh Human Rights

TWENTY YEARS LATER: RECENT REPORTS HIGHLIGHT THE CONTINUING STRUGGLE FOR SIKH HUMAN RIGHTS As my auto rickshaw wound its way through New Delhi one July after- noon, I felt a peculiar sense of familiarity and sadness. While on the streets one can see the poverty associated with India's large population, what to me represented the greatest threat to the human rights movement in India was the road itself, one of the so-called "flyovers" superimposed on the city. Flyovers are roads that allow vehicles to rise above the narrow streets, beg- gars, cows, and potholes that swallow tires whole. For years, they have been touted as the answer to the congestion and chaos that' plague modern, ur- ban India. Although the flyovers do not hide the persistent problems be- low, from the perspective up above, the problems seem less urgent and the remedies less imperative. If the traffic keeps moving, the government ap- pears effective. Many of India's survival efforts employ the same strategy: adopt any means to keep moving. While the government creates powerless commissions and delays hearings on the widespread human rights viola- tions against minorities in India, recent reports such as Reduced to Ashes: The Insurgency and Human Rights in Punjab' and Twenty Years of Impunity: The November 1984 Pogroms of Sikhs in India2 focus our attention below, so that we may address and repair the damage caused by state violence. Although this Recent Development focuses on the condition of Sikhs, many other minority groups in India have been victimized, including Kashmiris, "Untouchables," and Muslims in Gujarat, to name only a few. -

Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale - Life, Mission, and Martyrdom

1 # siVgUr pqsAid @ SANT JARNAIL SINGH BHINDRANWALE - LIFE, MISSION, AND MARTYRDOM by Ranbir S. Sandhu ***** May 1997 ***** Sikh Educational and Religious Foundation, P.O. Box 1553, Dublin, Ohio 43017 SANT JARNAIL SINGH BHINDRANWALE'S LIFE, MISSION AND MARTYRDOM ***** 0 INTRODUCTION In June 1984, the Indian Government sent nearly a quarter million troops to Punjab, sealed the state from the rest of the world, and launched an attack, code-named 'Operation Bluestar', on the Darbar Sahib complex in Amritsar and over forty other gurdwaras1 in Punjab. Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, head of the Damdami Taksaal2, and many students and teachers belonging to the Taksaal, perished in the conflict. Several thousand men, women and children, mostly innocent pilgrims, also lost their lives in that attack. This invasion was followed by 'Operation Woodrose' in which the army, supported by paramilitary and police forces, swept through Punjab villages to eliminate 'anti-social elements'. These 'anti-social' elements were identified as Amritdharis3. Instructions given to the troops at that time stated4: 'Some of our innocent countrymen were administered oath in the name of religion to support extremists and actively participate in the act of terrorism. These people wear a miniature kirpan5 round their neck and are called Amritdhari ... Any knowledge of the 'Amritdharis' who are dangerous people and pledged to commit murders, arson and acts of terrorism should immediately be brought to the notice of the authorities. These people may appear harmless from outside but they are basically committed to terrorism. In the interest of all of us their identity and whereabouts must always be disclosed.' These instructions constituted unmistakably clear orders for genocide of all Sikhs formally initiated into their faith. -

OPERATION BLUESTAR': the Untold Story

'OPERATION BLUESTAR': The untold story Investigation Team : Amiya Rao, Aurbindo Ghose, Sunil Bhattacharya, Tejinder Ahuja and N.D.Pancholi EYE WITNESSES JUNE 1st JUNE 2nd JUNE 3rd JUNE 4th JUNE 5th JUNE 6th JUNE 7th GOV'T WHITE PAPER JOPDHPUR DETAINEES RETROSPECTION "Operation Bluestar" and "Ghallughara". Two different terms for the same episode - the Army action on the Golden Temple in June 1984. Two different meanings give to the same unprecedented event. "Operation Bluestar" in the Government's term, connoting a necessary military operation to flush out terrorists and recover arms from the Golden Temple, the implication being that it was an unavoidable cleansing act of purification. Where as "Ghallughara" is how the Sikhs of Punjab remember the episode, connoting aggression, massacre and religious persecution. The unmistakable allusion is to the killing in Punjab of tens of thousands of Sikhs by the Afgan raider, Ahmed Shah Abdali in 1762, after which the word "Ghallughara" was coined to become an integral part of the Punjabi folklore. The contrast between "Operation Bluestar" and "Ghallughara" as two different perceptions of the same reality is symptomatic of the wide gap between the official version and the people's recollections of what really happened at the Golden Temple when the army attacked it in June 1984. Listening to the gripping eye-witness accounts of those who were inside Golden Temple at that time, we felt the need to tell the truth, the as-yet untold story and in the process to correct the Government's version as put out by the Army, the Press, the Radio, the T.V. -

13510 Hon. Judy Biggert Hon. Eddie Bernice Johnson

13510 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS June 21, 2005 And in Congress, we have ignored our fun- went to The Mountain State to personally de- The Kilby Awards Foundation, which com- damental constitutional responsibility to inves- liver the items. She also spent one week in memorates ‘‘the power of one individual to tigate. each of the past three summers remodeling make a significant impact on society.’’ In addi- When the Abu Ghraib photos surfaced, the and rebuilding homes in poor communities tion to the Nobel Prize, Kilby received numer- House held a mere five hours of public hear- closer to home. ous honors and awards for his contributions to ings. The Senate review was more extensive When not helping others, Maggie has de- science, technology and the electronics indus- but stopped far short of assessing individual voted time to improving her public speaking try. accountability up the chain of command. and musical abilities. In addition, she has un- It has been said that the ultimate measure Our troops deserve better. Our nation de- dertaken intense training in Tae Kwan Do, of a person’s life is the extent to which they serves better. swimming, and cross training. She undertook made the world a better place. If this is the Some of the allegations that have been re- a three year study of the German language measure of worth in life, Dr. Kilby’s family, col- played repeatedly around the world may not and culture, which included three weeks living leagues and friends can attest to the success be true. President Bush calls them ‘‘absurd.’’ abroad with a German family. -

Danish Immigration Service

Danish Immigration Service _______________________________________________________________ Report on the Fact-finding Mission to Punjab (India) The Position of the Sikhs 21 March to 5 April 2000 Copenhagen, September 2000 Report on fact-finding mission to Punjab (India) List of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................4 2. TERMS OF REFERENCE FOR THE FACT-FINDING MISSION TO PUNJAB, INDIA.............................5 3. HISTORICAL AND POLITICAL BACKGROUND...........................................................................................7 4. DEMOGRAPHY ...................................................................................................................................................11 5. POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS..............................................................................12 5.1. THE CURRENT POLITICAL SITUATION ..............................................................................................................12 5.2. EDUCATION AND SCHOOLING..........................................................................................................................14 5.3. THE ECONOMY AND THE LABOUR MARKET .....................................................................................................15 6. THE SECURITY SITUATION............................................................................................................................17 -

Proclaimed Offenders

INFORMATION REGARDING PROCLAIMED PERSON / OFFENDER UNDER SECTION 83 OF CR.P.C. PERTAINING TO THE COURT OF SH.KISHORE KUMAR, SESSIONS JUDGE, KAPURTHALA Proclaimed Name of Gender Compliance of Sr. Officer PO / Name and Address of the Proclaimed P.O. declare order dated Provision of Sec Name of the Court Case no. Title of the case Proclaimed (Male/ Police Station Fir No. Date of FIR No. Proclaimed Person/ offender DD/MM/YYYY 83 Cr.P.C made Offender Female) Person PP yes or No SESSIONS JUDGE, S/O RAM LAL, R/O NINDOKI, P.S. SADAR, 1 SC/97/2017 STATE VS KAMALDEEP VARINDER SINGH M PO 21 06.02.2017 09.08.2019 YES KAPURTHALA SADAR, KAPURTHALA KAPUTHALA SESSIONS JUDGE, SC-149/01-10- STATE VS SURINDER SINGH SURINDER SINGH MADHOPUR COLONIA, PS SADAR 2 M PO SATNAMPURA 17 10.03.2018 13.09.2019 YES KAPURTHALA 2018 @ KAKU @ KAKU PHAGWARA SESSIONS JUDGE, STATE VS VARINDER SINGH VARINDER SINGH S/O SAROOP SINGH, JABBOWAL, PS 3 SC-72/2016 M PO BEGOWAL 9 2016 26.09.2019 YES KAPURTHALA @ MANGAL @ MANGAL BEGOWAL, KPT S/O SarOOP SINGH S/O WARYAM SESSIONS JUDGE, STATE VS VARINDER SINGH SATWINDER 4 SC-72/2016 M PO SINGH, JABBOWAL, PS BEGOWAL BEGOWAL 9 2016 26.09.2019 YES KAPURTHALA @ MANGAL SINGH @ PRINCE KPT SESSIONS JUDGE, STATE VS ARSHDEEP SINGH ARSHDEEP SINGH S/O SUKHJINDER SINGH, R/O SULTANPUR 5 SC-32/2019 M PO 10 2018 23.10.2019 YES KAPURTHALA @ ARSH @ ARSH PARVEZ NAGAR PS FATTUDHINGA LODHI SESSIONS JUDGE, STATE VS NAVJEET SINGH @ NAVJEET SINGH S/O DES RAJ, PATTI RAMU KI,PS 6 SC-177/2017 M PO DHILWAN 3 2017 15.11.2019 YES KAPURTHALA GORA @ GORA DHILWAN KAPURTHALA -

INDIA COMMITS SUICIDE by G.S.Dhillon

INDIA COMMITS SUICIDE by G.S.Dhillon. INTRODUCTION This study seeks to make an analysis of the Punjab history since 1947 leading to the Dharam Yudh Morcha, the Operation Blue Star, the Operation Wood Rose and the Accord of 1985. The Moicha and the demolition of Akal Takhat during the attack on the Golden Temple are major landmarks in the history of Punjab. We shall examine the events that led to the demolition and the im¨plications there of, whether or not these are going to leave a major scar on the life of Punjab, giving a turn to history. No doubt, these events are too recent for any proper historical analysis. But a watchful historian can certainly exercise his judgement and discern the broad trend of policies and events that have taken place in the last four decades. The need for a perceptive record of the forces and interests that have shaped the socio-political happeningss necessary, especially because many of the reports and writings on the subject are, to a great extent, superficial, journalistic or an evident attempt to camouflage and distort the realities of the situation and motives. Emotions have blurred facts. For example, issues of water, territory, language, etc., simple inter-state contro¨versies, became matters of confrontation between the Hindus and the Sikhs. All this has led to mutual mistrust and driven the two communities to develop antagonistic attitudes and to take almost intractable positions. It is true that a historian’s job is considerably hampered owing to the nonavailability of authentic information especially from Government records on the related issues.