Work for the Dole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kirsty Maccoll – Selsdon Girl

The Selsdon Gazette Volume 73. No. 820 November 2020 THE SELSDON GAZETTE Editor: [email protected] Website: www.selsdon-residents.co.uk Advertising Enquiries: Carlo Rappa, [email protected] Advertising payments and Treasurer: Mrs Choi Kim, [email protected] Distribution: Enquiries to Wendy Mikiel, [email protected] 020 8651 0470 Copy for the Gazette should reach the Editor by 20th of each month and email attachments should be in Word or PDF format. Advertisements must reach the Advertising Manager by 15th of each month, with payment in full received by close of business that day. There is no August Gazette. The view expressed by contributors to the Selsdon Gazette are their own and are not necessarily those of the Editor, the Selsdon Gazette or the Selsdon Residents’ Association. All letters printed as received. The publication of advertisements in the Selsdon Gazette does not imply any warranty on the part of the Selsdon Gazette or the Selsdon Residents’ Association as to the quality of services offered by the advertiser. Residents should make such enquiries as they think necessary about any provider of goods or services. Front cover image credit: A thank you to four Street Champions from Selsdon Baptist Church. Advertising Space Available 1 SELSDON RESIDENTS’[email protected] ASSOCIATION Executive Committee 2019/2020 President: R. H. R. Adamson Vice-Presidents: P. Holden, R. F. G. Rowsell. Chairman: Sheila Childs Vice-Chairman: Linda Morris Hon. Secretary: Janet Sharp Hon. Treasurer: Iris Jones -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 26 June 2020 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government led by Boris Johnson and key ministerial appointments for our sector after the December 2019 General Election and February 2020 Cabinet reshuffle. Following the Conservative Party’s compelling victory, the Government now holds a majority of 80 seats in the House of Commons. The life sciences sector is high on the Government’s agenda and Boris Johnson has pledged to make the UK “the leading global hub for life sciences after Brexit”. With its strong majority, the Government has the power to enact the policies supportive of the sector in the Conservatives 2019 Manifesto. All in all, this indicates a positive outlook for life sciences during this Government’s tenure. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministers and policy maker profiles................................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities relevant to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. Department Position Holder Relevant responsibility Holder in -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Her Majesty's Government and Her Official Opposition

Her Majesty’s Government and Her Official Opposition The Prime Minister and Leader of Her Majesty’s Official Opposition Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP || Leader of the Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn MP Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury (Chief Whip). He will attend Cabinet Rt Hon Mark Spencer MP remains || Nicholas Brown MP Treasurer of HM Household (Deputy Chief Whip) Stuart Andrew MP appointed Vice Chamberlain of HM Household (Government Whip) Marcus Jones MP appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP appointed || John McDonnell MP Chief Secretary to the Treasury - Cabinet Attendee Rt Hon Stephen Barclay appointed || Peter Dowd MP Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury Kemi Badenoch MP appointed Paymaster General in the Cabinet Office Rt Hon Penny Mordaunt MP appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, and Minister for the Cabinet Office Rt Hon Michael Gove MP remains Minister of State in the Cabinet Office Chloe Smith MP appointed || Christian Matheson MP Secretary of State for the Home Department Rt Hon Priti Patel MP remains || Diane Abbott MP Minister of State in the Home Office Rt Hon James Brokenshire MP appointed Minister of State in the Home Office Kit Malthouse MP remains Parliamentary Under Secretary of State in the Home Office Chris Philp MP appointed Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and First Secretary of State Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP remains || Emily Thornberry MP Minister of State in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office Rt Hon James Cleverly MP appointed Minister of State in the Foreign -

Daily Report Thursday, 29 April 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 29 April 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 29 April 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (04:42 P.M., 29 April 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 11 Energy Intensive Industries: ATTORNEY GENERAL 11 Biofuels 18 Crown Prosecution Service: Environment Protection: Job Training 11 Creation 19 Sentencing: Appeals 11 EU Grants and Loans: Iron and Steel 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 12 Facebook: Advertising 20 Aviation and Shipping: Carbon Foreign Investment in UK: Budgets 12 National Security 20 Bereavement Leave 12 Help to Grow Scheme 20 Business Premises: Horizon Europe: Quantum Coronavirus 12 Technology and Space 21 Carbon Emissions 13 Horticulture: Job Creation 21 Clean Technology Fund 13 Housing: Natural Gas 21 Companies: West Midlands 13 Local Government Finance: Job Creation 22 Coronavirus: Vaccination 13 Members: Correspondence 22 Deep Sea Mining: Reviews 14 Modern Working Practices Economic Situation: Holiday Review 22 Leave 14 Overseas Aid: China 23 Electric Vehicles: Batteries 15 Park Homes: Energy Supply 23 Electricity: Billing 15 Ports: Scotland 24 Employment Agencies 16 Post Offices: ICT 24 Employment Agencies: Pay 16 Remote Working: Coronavirus 24 Employment Agency Standards Inspectorate and Renewable Energy: Finance 24 National Minimum Wage Research: Africa 25 Enforcement Unit 17 Summertime -

Homes for Everyone

Homes for Everyone How to get Britain building and restore the home ownership dream Chris Philp MP NEW GENERATION cps.org.uk Homes for Everyone About the Author Chris Philp studied Physics at Oxford, graduating with a First in 1998. He began his career at McKinsey before becoming an entrepreneur. He floated his first business on the stock market and has founded and run businesses in distribution, finance and property. Chris was elected as the Conservative MP for Croydon South in 2015, served as a member of the Treasury Select Committee 2015-17 and was re-elected to Parliament in 2017. Chris also served on both the Housing and Planning Bill Committee and the Neighbourhood Planning Bill Committee in the 2015- 17 Parliament. New Generation ‘New Generation’ is the Centre for Policy Studies’ flagship programme, promoting new policy ideas from fresh Tory thinkers, including MPs from the 2015 and 2017 intakes. This is the second in the series, which will include reports from Rishi Sunak MP, Suella Fernandes MP, Bim Afolami MP, Luke Graham MP and others. To find out more, or to become a supporter of the programme, visit cps.org. uk/new-generation or email [email protected] Acknowledgements With special thanks to Ben Cowley, Tom Puddy and Tim Rowe for their extensive research work on this project. Thanks go to Robert Colvile of the Centre for Policy Studies for his encouragement, guidance and editing. I would also like to thank the dozens of industry experts and market participants who gave their time and views, but in particular Rt Hon Sir Oliver Letwin MP, Tony Pidgley CBE, Sam Hine, Craig Tabb, Richard Blakeway and Geoffrey Springer for their input during the preparation of this report. -

Kew Gardens (Leases) (No

Kew Gardens (Leases) (No. 2) Bill EXPLANATORY NOTES Explanatory notes to the Bill, prepared by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs with the consent of Zac Goldsmith, are published separately as Bill 158—EN. Bill 158 57/1 Kew Gardens (Leases) (No. 2) Bill CONTENTS 1 Power to grant a lease in respect of land at Kew Gardens 2 Extent, commencement and short title Bill 158 57/1 Kew Gardens (Leases) (No. 2) Bill 1 A BILL TO Provide that the Secretary of State’s powers in relation to the management of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, include the power to grant a lease in respect of land for a period of up to 150 years. E IT ENACTED by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present BParliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:— 1 Power to grant a lease in respect of land at Kew Gardens (1) The Secretary of State’s powers in relation to the management of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, include the power to grant a lease in respect of land for a period of up to 150 years. (2) Section 5 of the Crown Lands Act 1702 does not apply in respect of such a lease. 5 2 Extent, commencement and short title (1) This Act extends to England and Wales. (2) It comes into force at the end of the period of two months beginning with the day on which it is passed. -

Phil Thomas Page 1 of 5 02/06/2016

Page 1 of 5 Phil Thomas From: "Chris Philp MP" <[email protected]> Date: 17 May 2016 12:47 To: <[email protected]> Subject: Update from Chris Philp MP on Southern Rail, Coulsdon parking, Purley Re-cycling Centre and other issues Dear All I am continuing to work hard on local and national issues as Croydon South’s MP and this email contains updates on some local issues you may find of interest. I have also held 15 street stalls on Saturday mornings on high streets around the constituency in the past 8 months and met with hundreds of local residents. The first item below is about the appalling service offered by Southern Rail. I am hosting a public meeting with them on 24 th May – please do come along if you can. Please also forward this email to any friends, family and neighbours who may be interested. Southern Rail Public Meeting Southern Rail has been one of the biggest issues facing our neighbourhood for some time. The constant delays have plighted commuters and leisure travellers alike. I have been complaining to Ministers, Southern and Network Rail and it is now time for residents to get a chance to hear from the train companies directly. To this end, I am hosting a public meeting on 24 th May at 7.30pm at Purley United Reform Church (in the hall). This is at 906 Brighton Road, Purley CR8 2LN, next to the hospital. There is no parking on site, so people driving are advised to use the multi-storey or the pay & display hospital car park. -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 20 August 2019 This is a briefing for BIA members on the new Government led by Boris Johnson and key ministerial appointments for our sector. With 311 MPs, the Conservative Government does not have a parliamentary majority and the new Prime Minister may also have to contend with a number of his own backbenchers who are openly opposed to his premiership and approach to Brexit. It is currently being assumed that he is continuing the confidence and supply deal with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). If the DUP will support the Government in key votes, such as on his Brexit deal (if one emerges), the Queen's Speech and Budgets, Boris Johnson will a working majority of 1. However, this may be diminished by Conservative rebels and possible defections. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministers and policy maker profiles................................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities relevant to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. Department Position Holder -

Nexus Planning Riverside House 2A Southwark Bridge Road London

Our ref: APP/l5240/V/17/3174139 Nexus Planning Your ref: Riverside House 2a Southwark Bridge Road London SE1 9HA 3 December 2018 Dear Sirs TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 – SECTION 77 APPLICATION MADE BY THORNSETT GROUP AND PURLEY BAPTIST CHURCH LAND AT 1 RUSSELL HILL ROAD, 1-4 RUSSELL HILL PARADE, 2-12 BRIGHTON ROAD, PURLEY HALL, PURLEY BAPTIST CHURCH, BANSTEAD ROAD, 1-9 BANSTEAD ROAD, PURLEY, CR8 2LE APPLICATION REF: 16/02994/P 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of David Nicholson RIBA IHBC, who held a public local inquiry on 9- 17 January 2018 into your client’s application for planning permission for the demolition of existing buildings on two sites; erection of a 3 to 17 storey development on the ‘Island Site’ (Purley Baptist Church, 1 Russell Hill Road, 1-4 Russell Hill Parade, 2-12 Brighton Road, Purley Hall), comprising 114 residential units, community and church space and a retail unit; and a 3 to 8 storey development on the ‘South Site’ (1-9 Banstead Road) comprising 106 residential units, and associated landscaping and works, in accordance with application ref: 16/02994/P, dated 20 May 2016. 2. On 12 April 2017, the Secretary of State directed, in pursuance of Section 77 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, that your client’s application be referred to him instead of being dealt with by the local planning authority. Inspector’s recommendation and summary of the decision 3. The Inspector recommended that planning permission be granted. -

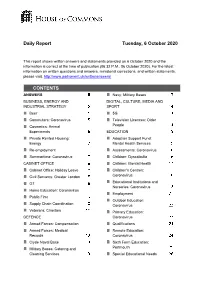

Daily Report Tuesday, 6 October 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Tuesday, 6 October 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 6 October 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:32 P.M., 06 October 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS Navy: Military Bases BUSINESS, ENERGY AND DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY SPORT Beer 5G Commuters: Coronavirus Television Licences: Older Cosmetics: Animal People Experiments EDUCATION Private Rented Housing: Adoption Support Fund: Energy Mental Health Services Re-employment Assessments: Coronavirus Summertime: Coronavirus Children: Dyscalculia CABINET OFFICE Children: Mental Health Cabinet Office: Holiday Leave Children's Centres: Civil Servants: Greater London Coronavirus G7 Educational Institutions and Nurseries: Coronavirus Home Education: Coronavirus Employment Public First Outdoor Education: Supply Chain Coordination Coronavirus Veterans: Charities Primary Education: DEFENCE Coronavirus Armed Forces: Compensation Qualifications Armed Forces: Medical Remote Education: Records Coronavirus Clyde Naval Base Sixth Form Education: Military Bases: Catering and Portmouth Cleaning Services Special Educational Needs Vocational Education: Finance Foreign, Commonwealth and ENVIRONMENT, FOOD AND Development Office: Staff RURAL AFFAIRS Hamas: Human Rights Animal Welfare Iran: Detainees Disability: Plastics Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe Environment Agency: -

Give and Take: How Conservatives Think About Welfare

How conservatives think about w elfare Ryan Shorthouse and David Kirkby GIVE AND TAKE How conservatives think about welfare Ryan Shorthouse and David Kirkby The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Bright Blue is an independent think tank and pressure group for liberal conservatism. Bright Blue takes complete responsibility for the views expressed in this publication, and these do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors. Director: Ryan Shorthouse Chair: Matthew d’Ancona Members of the board: Diane Banks, Philip Clarke, Alexandra Jezeph, Rachel Johnson First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Bright Blue Campaign ISBN: 978-1-911128-02-1 www.brightblue.org.uk Copyright © Bright Blue Campaign, 2014 Contents About the authors 4 Acknowledgements 5 Executive summary 6 1 Introduction 19 2 Methodology 29 3 How conservatives think about benefit claimants 34 4 How conservatives think about the purpose of welfare 53 5 How conservatives think about the sources of welfare 66 6 Variation amongst conservatives 81 7 Policies to improve the welfare system 96 Annex one: Roundtable attendee list 112 Annex two: Polling questions 113 Annex three: Questions and metrics used for social and economic conservative classification 121 About the authors Ryan Shorthouse Ryan is the Founder and Director of Bright Blue.