Britten's Op. 47, Five Flower Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Britten Spring Symphony Welcome Ode • Psalm 150

BRITTEN SPRING SYMPHONY WELCOME ODE • PSALM 150 Elizabeth Gale soprano London Symphony Chorus Alfreda Hodgson contralto Martyn Hill tenor London Symphony Orchestra Southend Boys’ Choir Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Spring Symphony, Op. 44* 44:44 For Soprano, Alto and Tenor solos, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Choir and Orchestra Part I 1 Introduction. Lento, senza rigore 10:03 2 The Merry Cuckoo. Vivace 1:57 3 Spring, the Sweet Spring. Allegro con slancio 1:47 4 The Driving Boy. Allegro molto 1:58 5 The Morning Star. Molto moderato ma giocoso 3:07 Part II 6 Welcome Maids of Honour. Allegretto rubato 2:38 7 Waters Above. Molto moderato e tranquillo 2:23 8 Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed. Adagio molto tranquillo 6:37 Part III 9 When will my May come. Allegro impetuoso 2:25 10 Fair and Fair. Allegretto grazioso 2:13 11 Sound the Flute. Allegretto molto mosso 1:24 Part IV 12 Finale. Moderato alla valse – Allegro pesante 7:56 3 Welcome Ode, Op. 95† 8:16 13 1 March. Broad and rhythmic (Maestoso) 1:52 14 2 Jig. Quick 1:20 15 3 Roundel. Slower 2:38 16 4 Modulation 0:39 17 5 Canon. Moving on 1:46 18 Psalm 150, Op. 67‡ 5:31 Kurt-Hans Goedicke, LSO timpani Lively March – Lightly – Very lively TT 58:48 4 Elizabeth Gale soprano* Alfreda Hodgson contralto* Martyn Hill tenor* The Southend Boys’ Choir* Michael Crabb director Senior Choirs of the City of London School for Girls† Maggie Donnelly director Senior Choirs of the City of London School† Anthony Gould director Junior Choirs of the City of London School -

"Aristocrats of High Fidelity"

l'inno and Violin DAME MYRA HESS plays Schumann and 'Request Program' The Great Lady of Music, in her first Angel Record... Schumann Etudes Symphonique and a delightful 'Request Pro- gram' on the 2nd side incl. two Scarlatti sonatas. Granados' Ln lIeja r eel Ruisevuer, Mendelssohn Song without Words, Waltz and Intermezzo of Brahms and her own famous arrangement of Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring. Angel 35591 Opera Arias. Choral Work. Operetta CALLAS AT LA SCALA: Her Great Revivals MOURA LYMPANY ploys Here Maria Meneghini Callas sings arias from forgotten opera Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 1 in F sharp minor masterpieces which have been revived as vehicles for her great art l'rokofiev Piano Concerto No. 1 in D flat and unique voice: Cherubini. MEDEA; Spontini. LA VES- Conductors: Nicolai Malko I RachmaninoffI ; Walter Su -kind TALE; Bellini. I PURITANI and LA SONNAMBULA. (Prokofiev). Philbannonia Orchestra. Angel 35568 Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala. Conductors: Tullio Serafin and Antonino Vogo. (booklet with texts) Angel 35304 CZIFFRA plays LISZT Hungarian Rhapsodies Nos. 2, 6, 12, 15 brilliant by THE MIKADO (Gilbert and Sullivan) Another Liszt recording the sensational Hungarian pianist. Gyorgy Cziffra. Angel 35429 2nd in the delightful new series of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent with an all -star east of Note: Cziffra plays Liszt Piano Concerto No. I and Hungarian leading British singers incl. Owen Brannigan I Mikado I. Richard Fantasia (35136) ; Liszt Recital (35528). Lewis (Nanki -Poo). Geraint Evans 1Ko.K.). Elsie Morison (Yum -Yum), Monica Sinclair IKatisha) . Glyndebourne Festival Chorus. Pro Arte Orchestra. -

Benjamin Britten: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1928: “Quatre Chansons Francaises” for soprano and orchestra: 13 minutes 1930: Two Portraits for string orchestra: 15 minutes 1931: Two Psalms for chorus and orchestra Ballet “Plymouth Town” for small orchestra: 27 minutes 1932: Sinfonietta, op.1: 14 minutes Double Concerto in B minor for Violin, Viola and Orchestra: 21 minutes (unfinished) 1934: “Simple Symphony” for strings, op.4: 14 minutes 1936: “Our Hunting Fathers” for soprano or tenor and orchestra, op. 8: 29 minutes “Soirees musicales” for orchestra, op.9: 11 minutes 1937: Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra, op. 10: 27 minutes “Mont Juic” for orchestra, op.12: 11 minutes (with Sir Lennox Berkeley) “The Company of Heaven” for two speakers, soprano, tenor, chorus, timpani, organ and string orchestra: 49 minutes 1938/45: Piano Concerto in D major, op. 13: 34 minutes 1939: “Ballad of Heroes” for soprano or tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.14: 17 minutes 1939/58: Violin Concerto, op. 15: 34 minutes 1939: “Young Apollo” for Piano and strings, op. 16: 7 minutes (withdrawn) “Les Illuminations” for soprano or tenor and strings, op.18: 22 minutes 1939-40: Overture “Canadian Carnival”, op.19: 14 minutes 1940: “Sinfonia da Requiem”, op.20: 21 minutes 1940/54: Diversions for Piano(Left Hand) and orchestra, op.21: 23 minutes 1941: “Matinees musicales” for orchestra, op. 24: 13 minutes “Scottish Ballad” for Two Pianos and Orchestra, op. 26: 15 minutes “An American Overture”, op. 27: 10 minutes 1943: Prelude and Fugue for eighteen solo strings, op. 29: 8 minutes Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, op. -

Fall 2012 Volume 39, No

ILLINOIS CHAPTER OF THE AMERICAN CHORAL DIRECTORS ASSOCIATION Fall 2012 Volume 39, No. 1 PODIUM techniques, ideas, song titles....IL- President’s Message ILLINOIS ACDA EXECUTIVE BOARD ACDA works well not just because of our guest clinicians, but because we have so many generous experts President in our own organization who are Beth Best HOT TIME IN THE OLD TOWN! willing to share with the rest of us. Hill Middle School [email protected] Thank you to all who attended and Dr. Karyl Carlson is putting the Past President helped with the Summer ReTreat 2013 Re-treat together, and has some exciting headliners and ses- Brett Goad in June! It was definitely a "hot time" in more ways than one! Our sions planned! Watch for her arti- Hinsdale South High School—retired director's chorus guest conductor, cles in the winter and spring issues [email protected] Dr. Josh Habermann, gave us a lot of The Podium. Also, please read President-Elect to think about in preparing and ex- Karyl Carlson pressing the varied music he chose Continued on page 2 Illinois State University for us. He was a joy to work with. Laura Farnell shared many of her [email protected] ideas for working with younger In this issue Treasurer voices. A highlight of her sessions Leslie Manfredo was the work she did with Deb President’s Message p. 1 Save the Date—ReTreat 2012 p. 2 Illinois State University Aurelius-Muir's boys, and practical Commissioning New Music p. 3 Just thinking...Why we do what p. 8 [email protected] tips for teaching the changing voice. -

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

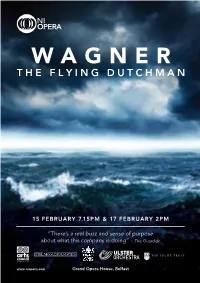

There's a Real Buzz and Sense of Purpose About What This Company Is Doing

15 FEBRUARY 7.15PM & 17 FEBRUARY 2PM “There’s a real buzz and sense of purpose about what this company is doing” ~ The Guardian www.niopera.com Grand Opera House, Belfast Welcome to The Grand Opera House for this new production of The Flying Dutchman. This is, by some way, NI Opera’s biggest production to date. Our very first opera (Menotti’s The Medium, coincidentally staged two years ago this month) utilised just five singers and a chamber band, and to go from this to a grand opera demanding 50 singers and a full symphony orchestra in such a short space of time indicates impressive progress. Similarly, our performances of Noye’s Fludde at the Beijing Music Festival in October, and our recent Irish Times Theatre Award nominations for The Turn of the Screw, demonstrate that our focus on bringing high quality, innovative opera to the widest possible audience continues to bear fruit. It feels appropriate for us to be staging our first Wagner opera in the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, but this production marks more than just a historical anniversary. Unsurprisingly, given the cost and complexities involved in performing Wagner, this will be the first fully staged Dutchman to be seen in Northern Ireland for generations. More unexpectedly, perhaps, this is the first ever new production of a Wagner opera by a Northern Irish company. Northern Ireland features heavily in this production. The opera begins and ends with ships and the sea, and it does not take too much imagination to link this back to Belfast’s industrial heritage and the recent Titanic commemorations. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Conducting Studies Conference 2016

Conducting Studies Conference 2016 24th – 26th June St Anne’s College University of Oxford Conducting Studies Conference 2016 24-26 June, St Anne’s College WELCOME It is with great pleasure that we welcome you to St Anne’s College and the Oxford Conducting Institute Conducting Studies Conference 2016. The conference brings together 44 speakers from around the globe presenting on a wide range of topics demonstrating the rich and multifaceted realm of conducting studies. The practice of conducting has significant impact on music-making across a wide variety of ensembles and musical contexts. While professional organizations and educational institutions have worked to develop the field through conducting masterclasses and conferences focused on professional development, and academic researchers have sought to explicate various aspects of conducting through focussed studies, there has yet to be a space where this knowledge has been brought together and explored as a cohesive topic. The OCI Conducting Studies Conference aims to redress this by bringing together practitioners and researchers into productive dialogue, promoting practice as research and raising awareness of the state of research in the field of conducting studies. We hope that this conference will provide a fruitful exchange of ideas and serve as a lightning rod for the further development of conducting studies research. The OCI Conducting Studies Conference Committee, Cayenna Ponchione-Bailey Dr John Traill Dr Benjamin Loeb Dr Anthony Gritten University of Oxford University of -

Walton - a List of Works & Discography

SIR WILLIAM WALTON - A LIST OF WORKS & DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Martin Rutherford, Penang 2009 See end for sources and legend. Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Catalogue No F'mat St Rel A BIRTHDAY FANFARE Description For Seven Trumpets and Percussion Completion 1981, Ischia Dedication For Karl-Friedrich Still, a neighbour on Ischia, on his 70th birthday First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Recklinghausen First 10-Oct-81 Westphalia SO Karl Rickenbacher Royal Albert Hall L'don 7-Jun-82 Kneller Hall G E Evans A LITANY - ORIGINAL VERSION Description For Unaccompanied Mixed Voices Completion Easter, 1916 Oxford First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.03 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - FIRST REVISION Description First revision by the Composer Completion 1917 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.14 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - SECOND REVISION Description Second revision by the Composer Completion 1930 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel St Johns, Cambridge ? Jan-62 George Guest St Johns, Cambridge 01a ARG ZRG -

07 – Spinning the Record

VI. THE STEREO ERA In 1954, a timid and uncertain record industry took the plunge to begin investing heav- ily in stereophonic sound. They were not timid and uncertain because they didn’t know if their system would work – as we have seen, they had already been experimenting with and working the kinks out of stereo sound since 1932 – but because they still weren’t sure how to make a home entertainment system that could play a stereo record. Nevertheless, they all had their various equipment in place, and so that year they began tentatively to make recordings using the new medium. RCA started, gingerly, with “alternate” stereo tapes of monophonic recording sessions. Unfortunately, since they were still uncertain how the results would sound on home audio, they often didn’t mark and/or didn’t file the alternate stereo takes properly. As a result, the stereo versions of Charles Munch’s first stereo recordings – Berlioz’ “Roméo et Juliette” and “Symphonie Fanastique” – disappeared while others, such as Fritz Reiner’s first stereo re- cordings (Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra” and the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 with Ar- thur Rubinstein) disappeared for 20 years. Oddly enough, their prize possession, Toscanini, was not recorded in stereo until his very last NBC Symphony performance, at which he suf- fered a mental lapse while conducting. None of the performances captured on that date were even worth preserving, let alone issuing, and so posterity lost an opportunity to hear his last half-season with NBC in the excellent sound his artistry deserved. Columbia was even less willing to pursue stereo. -

Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Thursday 18 May 2017 7.30pm Barbican Hall Vaughan Williams Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus Brahms Double Concerto INTERVAL Holst The Planets – Suite Sir Mark Elder conductor Roman Simovic violin Tim Hugh cello Ladies of the London Symphony Chorus London’s Symphony Orchestra Simon Halsey chorus director Concert finishes approx 9.45pm Supported by Baker McKenzie 2 Welcome 18 May 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican. BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2017 This evening we are joined by Sir Mark Elder for the second of two concerts this season, as he conducts The London Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with a programme of Vaughan Williams, Brahms and Holst. BMW and conducted by Valery Gergiev, performs an all-Rachmaninov programme in London’s Trafalgar It is always a great pleasure to see the musicians Square this Sunday 21 May, the sixth concert in of the LSO appear as soloists with the Orchestra. the Orchestra’s annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics Tonight, after Vaughan Williams’ Five Variants of series, free and open to all. Dives and Lazarus, the LSO’s Leader Roman Simovic and Principal Cello Tim Hugh take centre stage for lso.co.uk/openair Brahms’ Double Concerto. We conclude the concert with Holst’s much-loved LSO WIND ENSEMBLE ON LSO LIVE The Planets, for which we welcome the London Symphony Chorus and Choral Director Simon Halsey. The new recording of Mozart’s Serenade No 10 The LSO premiered the complete suite of The Planets for Wind Instruments (‘Gran Partita’) by the LSO Wind in 1920, and we are thrilled that the 2002 recording Ensemble is now available on LSO Live.