Forest for People's Welfare: Stories from the Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainability of Oxbow Barito Mati Lake, South Barito Regency, Central Kalimantan Province, Indonesia

J. Bio. & Env. Sci. 2014 Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences (JBES) ISSN: 2220-6663 (Print) 2222-3045 (Online) Vol. 5, No. 4, p. 1-12, 2014 http://www.innspub.net RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Analysis on fishing fisheries resources management sustainability of oxbow barito mati lake, south barito regency, central kalimantan province, Indonesia Sweking1,2, Marsoedi3, Zaenal Kusuma4, Idiannoor Mahyudin5 1Doctorate Program In Agricultural Sciences, Depart. Natural Resources and Environmental Management, Brawijaya University, Malang, East Java, Indonesia 2Teaching Staff at Faculty of Agriculture, Palangkaraya University, Indonesia 3Professor at the Aquatic Resources Management, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia 4Professor In Soil Science, Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia 5Professor In Fisheries Economics, Lambung Mangkurat University, Banjarbaru, Indonesia Article published on October 07, 2014 Key words: Oxbow, fisheries resources, sustainability index, sustainability status. Abstract Oxbow Barito Mati Lake in South Barito is important not only from economic aspect, but hydrological and ecological aspects as well. Lake and its flooding areas directly connecting to Barito River is an important area for fish migration, spawning and growth. Nevertheless, in its development, the important role of Oxbow Barito Mati Lake seems to be not meaningful due to human activities, such as pollution, excessive lake resources utilization, land conversion, residential development, and etc. This, of course, has negative impact on the lake sustainability itself due to degraded aquatic and fisheries resources which then affect the lake function and benefit values in the present or future. This study was aimed at reviewing the freshwater fishries contribugtion to the gross regional domestic product of South Barito Regency, reconsidering the sustainable fishing fisheries resources management in Oxbow Barito Mati Lake, South Barito Regency, and producing the sustainable fishing fisheries resources management strategy in the lake. -

33 CHAPTER II GENERAL DESCRIPTION of SERUYAN REGENCY 2.1. Geographical Areas Seruyan Regency Is One of the Thirteen Regencies W

CHAPTER II GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF SERUYAN REGENCY 2.1. Geographical Areas Seruyan Regency is one of the thirteen regencies which comprise the Central Kalimantan Province on the island of Kalimantan. The town of Kuala Pembuang is the capital of Seruyan Regency. Seruyan Regency is one of the Regencies in Central Kalimantan Province covering an area around ± 16,404 Km² or ± 1,670,040.76 Ha, which is 11.6% of the total area of Central Kalimantan. Figure 2.1 Wide precentage of Seruyan regency according to Sub-District Source: Kabupaten Seruyan Website 2019 Based on Law Number 5 Year 2002 there are some regencies in Central Kalimantan Province namely Katingan regency, Seruyan regency, Sukamara regency, Lamandau regency, Pulang Pisau regency, Gunung Mas regency, Murung Raya regency, and Barito Timur regency 33 (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Year 2002 Number 18, additional State Gazette Number 4180), Seruyan regency area around ± 16.404 km² (11.6% of the total area of Central Kalimantan). Administratively, to bring local government closer to all levels of society, afterwards in 2010 through Seruyan Distric Regulation Number 6 year 2010 it has been unfoldment from 5 sub-districts to 10 sub-districts consisting of 97 villages and 3 wards. The list of sub-districts referred to is presented in the table below. Figure 2.2 Area of Seruyan Regency based on District, Village, & Ward 34 Source: Kabupaten Seruyan Website 2019 The astronomical position of Seruyan Regency is located between 0077'- 3056' South Latitude and 111049 '- 112084' East Longitude, with the following regional boundaries: 1. North border: Melawai regency of West Kalimantan Province 2. -

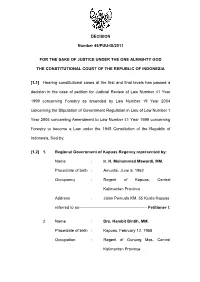

DECISION Number 45/PUU-IX/2011 for the SAKE OF

DECISION Number 45/PUU-IX/2011 FOR THE SAKE OF JUSTICE UNDER THE ONE ALMIGHTY GOD THE CONSTITUTIONAL COURT OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA [1.1] Hearing constitutional cases at the first and final levels has passed a decision in the case of petition for Judicial Review of Law Number 41 Year 1999 concerning Forestry as amended by Law Number 19 Year 2004 concerning the Stipulation of Government Regulation in Lieu of Law Number 1 Year 2004 concerning Amendment to Law Number 41 Year 1999 concerning Forestry to become a Law under the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, filed by: [1.2] 1. Regional Government of Kapuas Regency represented by: Name : Ir. H. Muhammad Mawardi, MM. Place/date of birth : Amuntai, June 5, 1962 Occupancy : Regent of Kapuas, Central Kalimantan Province Address : Jalan Pemuda KM. 55 Kuala Kapuas referred to as --------------------------------------------------- Petitioner I; 2. Name : Drs. Hambit Bintih, MM. Place/date of birth : Kapuas, February 12, 1958 Occupation : Regent of Gunung Mas, Central Kalimantan Province 2 Address : Jalan Cilik Riwut KM 3, Neighborhood Ward 011, Neighborhood Block 003, Kuala Kurun Village, Kuala Kurun District, Gunung Mas Regency referred to as -------------------------------------------------- Petitioner II; 3. Name : Drs. Duwel Rawing Place/date of birth : Tumbang Tarusan, July 25, 1950 Occupation : Regent of Katingan, Central Kalimantan Province Address : Jalan Katunen, Neighborhood Ward 008, Neighborhood Block 002, Kasongan Baru Village, Katingan Hilir District, Katingan Regency referred to as -------------------------------------------------- Petitioner III; 4. Name : Drs. H. Zain Alkim Place/date of birth : Tampa, July 11, 1947 Occupation : Regent of Barito Timur, Central Kalimantan Province Address : Jalan Ahmad Yani, Number 97, Neighborhood Ward 006, Neighborhood Block 001, Mayabu Village, Dusun Timur District, Barito Timur Regency 3 referred to as ------------------------------------------------- Petitioner IV; 5. -

Strategi Pemerintah Kabupaten Sukamara Dalam Pemberdayaan

WACANA Vol. 13 No. 1 Januari 2010 ISSN. 1411-0199 STRATEGI PEMERINTAH KABUPATEN SUKAMARA DALAM PEMBERDAYAAN EKONOMI MASYARAKAT (Studi Tentang Pemberdayaan Usaha Kecil Pembuatan Kerupuk Ikan Di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara Propinsi Kalimantan Tengah) Strategies of the Sukamara Regency Government in Empowering Community Economic (Study about Empowerment of Fish Chips Small Businesses at the Sukamara Sub District, Central Kalimantan). ISWAN GEMAYANA Mahasiswa Program Magister Ilmu Administrasi Publik, PPSUB Sukanto dan Ismani HP Dosen Jurusan Ilmu Administrasi Publik, FIAUB ABSTRAK Penelitian berawal dari latar belakang masalah tentang upaya oleh pemerintah kabupaten Sukamara dalam memberdayakan usaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk ikan di Kecamatan Sukamara kabupaten Sukamara mengingat sampai saat ini, masih belum mampu menjadikan usaha kecil pembuat kerupuk ikan sebagai produk unggulan. Tujuan dari penelitian ini ialah untuk mendiskripsikan dan menganalisis: (1) Potensi usaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk ikan di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara, (2) Strategi pemberdayaan usaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk ikan di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara dan (3) Faktor-faktor penghambat dan pendukung dalam pemberdayaan usaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk ikan di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara. Jenis penelitian yang dilakukan dalam penelitian ini adalah penelitian kwalitatif dengan lokasi penelitian pada pengusaha kecil pembuatan kerupuk di Kecamatan Sukamara Kabupaten Sukamara Propinsi Kalimantan Tengah. Analisis yang dilakukan dengan mengikuti model Miles Huberman yaitu analisis interaktif. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa upaya yang dilakukan oleh Pemerintah Kabupaten Sukamara dalam memberdayakan pengusaha kecil pembuat kerupuk ikan telah dilakukan, namun belum bisa dilakukan secara maksimal mengingat Pemerintah Kabupaten Sukamara sebagai pemerintahan baru hasil pemekaran mengalami beberapa kendala diantaranya keterbatasan personil, alokasi anggaran masih terserap untuk pembuatan infrastruktur gedung-gedung perkantoran pemerintah dan penataan organisasi kedalam. -

Identification of Factors Affecting Food Productivity Improvement in Kalimantan Using Nonparametric Spatial Regression Method

Modern Applied Science; Vol. 13, No. 11; 2019 ISSN 1913-1844 E-ISSN 1913-1852 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Identification of Factors Affecting Food Productivity Improvement in Kalimantan Using Nonparametric Spatial Regression Method Sifriyani1, Suyitno1 & Rizki. N. A.2 1Statistics Study Programme, Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Mulawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia. 2Mathematics Education Study Programme, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Mulawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia. Correspondence: Sifriyani, Statistics Study Programme, Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Mulawarman University, Samarinda, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: August 8, 2019 Accepted: October 23, 2019 Online Published: October 24, 2019 doi:10.5539/mas.v13n11p103 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v13n11p103 Abstract Problems of Food Productivity in Kalimantan is experiencing instability. Every year, various problems and inhibiting factors that cause the independence of food production in Kalimantan are suffering a setback. The food problems in Kalimantan requires a solution, therefore this study aims to analyze the factors that influence the increase of productivity and production of food crops in Kalimantan using Spatial Statistics Analysis. The method used is Nonparametric Spatial Regression with Geographic Weighting. Sources of research data used are secondary data and primary data obtained from the Ministry of Agriculture -

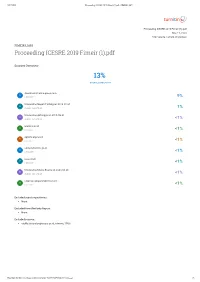

9% 1% <1% <1% <1% <1% <1% <1% <1%

11/17/2020 Proceeding ICESRE 2019 Fimeir (1).pdf - FIMEIR LIADI Proceeding ICESRE 2019 Fimeir (1).pdf Nov 17, 2020 5792 words / 31069 characters FIMEIR LIADI Proceeding ICESRE 2019 Fimeir (1).pdf Sources Overview 13% OVERALL SIMILARITY download.atlantis-press.com 1 INTERNET 9% Universitas Negeri Padang on 2018-01-31 2 SUBMITTED WORKS 1% Universitas Airlangga on 2019-03-21 3 SUBMITTED WORKS <1% www.nu.or.id 4 INTERNET <1% eprints.uny.ac.id 5 INTERNET <1% sinta.ristekbrin.go.id 6 INTERNET <1% issuu.com 7 INTERNET <1% Universitas Mercu Buana on 2020-06-23 8 SUBMITTED WORKS <1% ejournal.iainpurwokerto.ac.id 9 INTERNET <1% Excluded search repositories: None Excluded from Similarity Report: None Excluded sources: digilib.iain-palangkaraya.ac.id, internet, 100% https://iain.turnitin.com/viewer/submissions/oid:16479:3847586/print?locale=en 1/8 11/17/2020 Proceeding ICESRE 2019 Fimeir (1).pdf - FIMEIR LIADI 2Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 417 12nd International Conference on Education and Social Science Research (ICESRE 2019) 6 The Ulama Identity Politics in 2019 Presidential Election Contestation at the 4.0 Industrial Era in Central Kalimantan Liadi, Fimeir1* Anwar, Khairil2 Syar’i, Ahmad3 1,2,3IAIN Palangka Raya, Palangkaraya, Indonesia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT The 2019 Presidential Election Contestation in the 4.0 Industrial Era is very interesting to be examined, specifically related to the Political Activities of Religious Identity. There are two presidential and vice presidential candidates appointed by the General Election Commission (KPU), namely the pair of Joko Widodo and K.H. -

The Meaning of Actor Social Action in Distribution of Subsidized Fertilizers in Pulang Pisau District, Central Kalimantan Province

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 7, Issue 4, April 2020, PP 44-51 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0704006 www.arcjournals.org The Meaning of Actor Social Action in Distribution of Subsidized Fertilizers in Pulang Pisau District, Central Kalimantan Province Baini1, Ishomuddin2*, Rinikso Kartono3, Tri Sulistyaningsih4 1Doctor Candidate of Social and Political Sciences of University of Muhammadiyah Malang 2Professor of Sociology of Islamic Society of University of Muhammadiyah Malang, 3Doctor of Social Welfare of University of Muhammadiyah Malang 4Doctor of Sociology of University of Muhammadiyah Malang *Corresponding Author: Ishomuddin, Doctor Candidate of Social and Political Sciences of University of Muhammadiyah Malang, Indonesia Abstract: Government policies on subsidized fertilizers as well as the distribution of subsidized fertilizers have been carried out comprehensively starting from the preparation of fertilizer demand plans, the highest ecera price of subsidized fertilizers, distribution systems from producers to farmers or farmer groups. But apparently there are still some problems found in the field, namely the lack of fertilizer supply, causing a shortage of stock which resulted in a surge in subsidized fertilizer HET, and still found the distribution of subsidized fertilizer that is not on target as stated in the RDKK. Some of the causes of the above problems are (a) problems in preparing RDKK, (b) differences in fertilizer prices (disparities), (c) unrealistic supplier margins (d) limited subsidized fertilizer budgets, and (e) less optimal supervision. From this phenomenon, the purpose of this study is to understand the meaning of social actions of actors in the distribution of subsidized fertilizer in Pulang Pisau Regency, Central Kalimantan Province. -

E:\Hadiprayitno\Gezet\00Voorwerk Handelseditie.Wpd

Hazard or Right? The Dialectics of Development Practice and the Internationally Declared Right to Development, with Special Reference to Indonesia SCHOOL OF HUMAN RIGHTS RESEARCH SERIES, Volume 31 The titles published in this series are listed at the end of this volume. Hazard or Right? The Dialectics of Development Practice and the Internationally Declared Right to Development, with Special Reference to Indonesia Irene Hadiprayitno Antwerp – Oxford – Portland Cover photograph: From the courtesy of Himpunan Pengembangan Jalan Indonesia (HPJI), The Province of Yogyakarta, Jembatan Kebon Agung II Typesetting: G.J. Wiarda Institute for Legal Research, Boothstraat 6, 3512 BW Utrecht. Irene Hadiprayitno Hazard or Right? The Dialectics of Development Practice and the Internationally Declared Right to Development, with Special Reference to Indonesia ISBN 978-90-5095-932-2 D/2009/7849/40 NUR 828 © 2009 Intersentia www.intersentia.com Behoudens uitzondering door de wet gesteld, mag zonder schiftelijke toestemming van de rechthebbende(n) op het auteursrecht c.q. de uitgevers van deze uitgave, door de rechthebbende(n) gemachtigd namens hem (hen) op te treden, niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm of anderszins, hetgeen ook van toepassing is op de gehele of gedeeltelijke bewerking. De uitgevers zijn met uitsluiting van ieder ander onherroepelijk door de auteur gemachtigd de door derden verschuldigde vergoedingen van copiëren, als bedoeld in artikel 17 lid 2 der Auteurswet 1912 en in het KB van 20-6-’64 (Stb. 351) ex artikel 16b der Auteurswet 1912, te doen innen door (en overeenkomstig de reglementen van) de Stichting Reprorecht te Amsterdam. -

Usaid Lestari

USAID LESTARI LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL BRIEF OPTIMIZATION OF REFORESTATION FUND IN CENTRAL KALIMANTAN MARCH 2020 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Tetra Tech ARD. This publication was prepared for review by the United States Agency for International Development under Contract # AID-497-TO-15-00005. The period of this contract is from July 2015 to July 2020. Implemented by: Tetra Tech P.O. Box 1397 Burlington, VT 05402 Tetra Tech Contacts: Reed Merrill, Chief of Party [email protected] Rod Snider, Project Manager [email protected] USAID LESTARI – Optimization of Reforestation Fund in Central Kalimantan Page | i LESSONS LEARNED TECHNICAL BRIEF OPTIMIZATION OF REFORESTATION FUND IN CENTRAL KALIMANTAN MARCH 2020 DISCLAIMER This publication is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Tetra Tech ARD and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID LESTARI – Optimization of Reforestation Fund in Central Kalimantan Page | ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms and Abbreviations iv Executive Summary 1 Introduction: Reforestation Fund, from Forest to Forest 3 Reforestation Fund in Central Kalimantan Province: Answering the Uncertainty 9 LESTARI Facilitation: Optimization of Reforestation Fund through Improving FMU Role 15 Results of Reforestation Fund Optimization -

59 Conflicts Between Corporations and Indigenous Communities

International Journal of Management and Administrative Sciences (IJMAS) (ISSN: 2225-7225) Vol. 4, No. 05, (59-68) www.ijmas.org Conflicts between Corporations and Indigenous Communities Cases of Plantation Businesses in Central Kalimantan Sidik R. Usop Abstract Conflicts between corporations and indigenous communities have provided experience and lessons which should be understood to help building a dialogical way to generate long-term oriented deal so that the lives of corporations benefit the lives of indigenous communities. Key words: Corporations, Indigenous Communities and Conflicts 59 Copyright ©Pakistan Society of Business and Management Research International Journal of Management and Administrative Sciences (IJMAS) (ISSN: 2225-7225) Vol. 4, No. 05, (59-68) www.ijmas.org 1. INTRODUCTION The relationship between communities and palm oil Plantation Companies in Central Kalimantan is in a less friendly atmosphere and conflicts. Usop (2011) called it as a structural conflict because in this conflict, the company was considered as a detrimental party which had been exploitating the natural resources, causing a variety of problems, displacing public land for fruit crops and rubber plants as well as violating traditional land and cultural sites. Dody Proyogo (2004) suggested that the companies were the sources of problems such as compensation problems, environmental pollutions, natural resources and local economic losses as well as labor mobilizes. The bottom line is a contradiction in the utilization of natural resources which is considered ignoring the aspirations and interests of the communities. Related to the above issue, Bennett, J (2002) mentioned that the international corporations should increase the economic inclusion and social justice or they will be accused of contributing to conflict and violence. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 84 International Conference on Ethics in Governance (ICONEG 2016) Local Knowledge of Dayak Tomun Lamandau About the Honey Harvest Brian L. Djumaty Antakusuma University Pangkalan Bun, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract--Culture is the result of a set of experiences provided by observations and documents [5]. This type of research is nature. like the local knowledge to harvest honey by society descriptive. Descriptive Aiming to describe accurately the Tomun Lamandau, Central Borneo. This research uses characteristics and focus on the fundamental question of descriptive qualitative method and data collection techniques "How" for trying to acquire and convey the facts clearly and including observation, interviews, and documentation. The accurately [6]. The goal is to describe accurately the results showed that society already have knowledge about protecting nature in a way as not to damage the honeycomb and characteristics of a phenomenon or problem studied so as to tree. Some of the equipment used to harvest the honey has been convey the facts clearly and accurately [7]. modified. B. Research Field Keywords: Local Knowledge, Dayaknese, Protecting Nature This research was carried out starting from a survey of Introduction student placement Field Work Experience (KKN) Antakusuma I. INTRODUCTION University in Kabupatan Lamandau. Writer fascinated by the Based on data from the Central Statistics Agency (BPS) in culture of the local community. One of them is the knowledge 2010, there are more than 300 ethnic groups or tribes 1.340 or of local communities to harvest the honey. more than 300 ethnic groups. The diversity of the culture of This research was conducted in June-August 2016. -

Analysis of Leading Commodities in the North Barito District, Central Kalimantan Province Ary Sudarta*, Andi Tenri Sompa, Muhammad Riduansyah Syafari

Saudi Journal of Economics and Finance Abbreviated Key Title: Saudi J Econ Fin ISSN 2523-9414 (Print) |ISSN 2523-6563 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: http://saudijournals.com Original Research Article Analysis of Leading Commodities in the North Barito District, Central Kalimantan Province Ary Sudarta*, Andi Tenri Sompa, Muhammad Riduansyah Syafari Masters in Development Administration, Postgraduate Program, Lambung Mangkurat University, Banjarmasin, Indonesia DOI: 10.36348/sjef.2021.v05i02.006 | Received: 10.02.2021 | Accepted: 22.02.2021 | Published: 26.02.2021 *Corresponding author: Ary Sudarta Abstract This study aims to determine the superior commodity of plantation crops in the agricultural, forestry and fishery business fields as well as to what extent the ratio of income per capita of North Barito Regency and income per capita of superior sector farmers of plantation crops in North Barito Regency, Central Kalimantan Province. This research uses secondary data analysis method with literature study. Secondary data is in the form of production data, the number of household heads who have tried on plantation crop commodities and other supporting data in the last five years. The data analysis technique used in this research is Location Quotient (LQ) analysis as well as analysis of plantation crop farmers' per capita income and analysis of income per capita in North Barito Regency. Based on the results of the study showed that the superior plantation crops based on production were rubber, coffee, areca nut, cocoa, and candlenut. Meanwhile, based on the planted area, namely rubber, areca nut, cocoa, and candlenut. Based on the comparison of plantation crop farmers 'income per capita to PDRB per capita in North Barito Regency, there is a huge imbalance, farmers' per capita income is lower than PDRB per capita.