5 Toxicity of Aromatic Plants and Their Constituents Against

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phragmites Australis

Journal of Ecology 2017, 105, 1123–1162 doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12797 BIOLOGICAL FLORA OF THE BRITISH ISLES* No. 283 List Vasc. PI. Br. Isles (1992) no. 153, 64,1 Biological Flora of the British Isles: Phragmites australis Jasmin G. Packer†,1,2,3, Laura A. Meyerson4, Hana Skalov a5, Petr Pysek 5,6,7 and Christoph Kueffer3,7 1Environment Institute, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; 3Institute of Integrative Biology, Department of Environmental Systems Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, CH-8092, Zurich,€ Switzerland; 4University of Rhode Island, Natural Resources Science, Kingston, RI 02881, USA; 5Institute of Botany, Department of Invasion Ecology, The Czech Academy of Sciences, CZ-25243, Pruhonice, Czech Republic; 6Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, CZ-12844, Prague 2, Czech Republic; and 7Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Matieland 7602, South Africa Summary 1. This account presents comprehensive information on the biology of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. (P. communis Trin.; common reed) that is relevant to understanding its ecological char- acteristics and behaviour. The main topics are presented within the standard framework of the Biologi- cal Flora of the British Isles: distribution, habitat, communities, responses to biotic factors and to the abiotic environment, plant structure and physiology, phenology, floral and seed characters, herbivores and diseases, as well as history including invasive spread in other regions, and conservation. 2. Phragmites australis is a cosmopolitan species native to the British flora and widespread in lowland habitats throughout, from the Shetland archipelago to southern England. -

1. Padil Species Factsheet Scientific Name: Common Name Image

1. PaDIL Species Factsheet Scientific Name: Anthrenocerus australis (Hope, 1843) (Coleoptera: Dermestidae: Megatominae) Common Name Australian carpet beetle Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/Pest/Main/135939 Image Library Australian Biosecurity Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/ Partners for Australian Biosecurity image library Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment https://www.awe.gov.au/ Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Western Australia https://dpird.wa.gov.au/ Plant Health Australia https://www.planthealthaustralia.com.au/ Museums Victoria https://museumsvictoria.com.au/ 2. Species Information 2.1. Details Specimen Contact: CSIRO - ANIC - Author: Walker, K. Citation: Walker, K. (2007) Australian carpet beetle(Anthrenocerus australis)Updated on 5/2/2011 Available online: PaDIL - http://www.padil.gov.au Image Use: Free for use under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY- NC 4.0) 2.2. URL Live link: http://www.padil.gov.au/pests-and-diseases/Pest/Main/135939 2.3. Facets Status: Native Australian Pest Species Group: Beetles Commodity Overview: Field Crops and Pastures, Horticulture Commodity Type: Grains, Stored Products, Animal, Cotton & other fibres Distribution: Europe and Northern Asia, Australasian - Oceanian 2.4. Other Names Anthremis australis Hope, 1845 Anthrenus australis Hope, 1843 Anthrenus australis Hope, 1843 Cryptorhopalum erichsoni Reitter, 1881 Cryptorhopalum erichsoni Reitter, 1881 Trogoderma riguum Hope, 1845 Trogoderma riguum Erichson, 1842 2.5. Diagnostic Notes Live larva footage Adults of Anthrenocerus are distinguished from other dermestids by: - Presence of medin ocellus - Antennae with distinct 3-segmented club that fits tightly into a deep and margined sulci in the hypermeron; - Absence of scale-shaped setae and presence of coloured hairs on body; - Body narrowly ovate body widest at elytral hymera. -

A Review of Diapause and Tolerance to Extreme Temperatures to Dermestids (Coleoptera)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OPUS: Open Uleth Scholarship - University of Lethbridge Research Repository University of Lethbridge Research Repository OPUS https://opus.uleth.ca Faculty Research and Publications Laird, Robert Wilches, D.M. 2016-06-14 A review of diapause and tolerance to extreme temperatures to dermestids (Coleoptera) Department of Biological Sciences https://hdl.handle.net/10133/4516 Downloaded from OPUS, University of Lethbridge Research Repository 1 A REVIEW OF DIAPAUSE AND TOLERANCE TO EXTREME TEMPERATURES IN DERMESTIDS 2 (COLEOPTERA) 3 4 5 D.M. Wilches a,b, R.A. Lairdb, K.D. Floate a, P.G. Fieldsc* 6 7 a Lethbridge Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge, AB T1J 8 4B1, Canada 9 b Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB T1K 3M4 10 Canada 11 c Morden Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Winnipeg, MB R3T 12 2M9, Canada 13 14 * Corresponding author: [email protected]. 15 Abstract 16 Numerous species in Family Dermestidae (Coleoptera) are important economic pests of stored 17 goods of animal and vegetal origin, and museum specimens. Reliance on chemical methods for 18 of control has led to the development of pesticide resistance and contamination of treated 19 products with insecticide residues. To assess its practicality as an alternate method of control, 20 we review the literature on the tolerance of dermestids to extreme hot and cold temperatures. 21 The information for dermestid beetles on temperature tolerance is fragmentary, experimental 22 methods are not standardized across studies, and most studies do not consider the role of 23 acclimation and diapause. -

Checklist of Dermestidae (Insecta: Coleoptera: Bostrichoidea) of the United States

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 6-25-2021 Checklist of Dermestidae (Insecta: Coleoptera: Bostrichoidea) of the United States Jiří Háva Andreas Herrmann Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A journal of world insect systematics INSECTA MUNDI 0871 Checklist of Dermestidae (Insecta: Coleoptera: Bostrichoidea) Page Count: 16 of the United States Jiří Háva Author et al. Forestry and Game Management Research Institute Strnady 136, CZ-156 00 Praha 5 - Zbraslav, Czech Republic Andreas Herrmann Bremervörder Strasse 123, 21682 Stade, Germany Date of issue: June 25, 2021 Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc., Gainesville, FL Háva J, Herrmann A. 2021. Checklist of Dermestidae (Insecta: Coleoptera: Bostrichoidea) of the United States. Insecta Mundi 0871: 1–16. Published on June 25, 2021 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P.O. Box 141874 Gainesville, FL 32614-1874 USA http://centerforsystematicentomology.org/ Insecta Mundi is a journal primarily devoted to insect systematics, but articles can be published on any non- marine arthropod. Topics considered for publication include systematics, taxonomy, nomenclature, checklists, faunal works, and natural history. Insecta Mundi will not consider works in the applied sciences (i.e. medi- cal entomology, pest control research, etc.), and no longer publishes book reviews or editorials. -

Vol 5 Part 3. Adults and Larvae of Hide, Larder and Carpet Beetles and Their Relatives

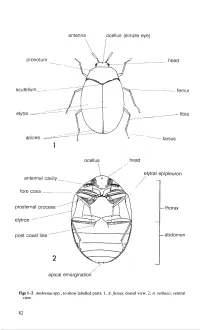

antenna ocellus (simple eye) I pronotum ____ head --------- - -- femur apices 1 ocellus head elytral epipleuron antenna! cavity __ / presternal process thorax elytron - --------------- post coxal line ------- abdomen 2 / / apical emargination Figs 1-2. Anthrenus spp., to show labelled parts. I, A.fuscus, dorsal view. 2, A. verbasci, ventral view. 82 coxa basal antenna! segment presternum ~head \\ \ apical antenna! segment hypomeron ~ I I antenna! club ......... elytral epipleuron / mesosternum coxal plate ~ trochanter 1 2 setal tuft / J I lateral impressed line tarsus / I I \ elytron visible abdominal sternite 3 Fig. 3. Ventral view of Dermestes sp., to show labelled parts. 83 Figs 4--7. 4- 5, Thylodrias contractus. 4, male. 5, female. 6, Trinodes sp., after Hinton (1945). 7, Thorictodes heydeni. Scale lines = 1.0 mm. 84 metepisternum I metasternum -~---a_b_d_o_m_en ---------- 8 hind coxa ocellus compound eye mouth parts 9 fore coxa 10 Figs 8-10. 8, diagram to show position of hind coxae of Trinodes hirtus. 9- 10, side view of head and prothorax (appendages removed). 9, Attagenus brunneus. 10, Megatoma undata. 85 [ 11 12 13 14 Figs 11-14. Ventral view of adult. 11 , Dermestes peruvianus. 12, Attagenus unicolor. 13, Trogoderma inc/usum. 14, Reesa vespulae. Scale lines = 1.0 mm. 86 Figs 15--20. Ventral view of adult. 15, Globicornis nigripes. 16, Megatoma unda ta. 17, Ctesias serra. 18, Anthrenus fuscus. 19, Anthrenocerus australis. 20, Trinodes hirtus. Scale lines = 1.0 mm. 87 Figs 21-24. Dermestes spp. 21, D. macu/atus. 22, D. frischii. 23, D. carnivorus. 24, D. ater. Scale line = 2.0 mm. All after Hinton (1945). -

Anthrenocerus Australis)

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. THE USE OF DOGS TO DETECT CARPET BEETLES (Anthrenocerus australis) A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Animal Science at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Chloe Phoon Koh Ee 2015 1 Abstract This study examined the ability of domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) to detect the scent of carpet beetle larvae (Anthrenocerus australis). These insects were introduced to New Zealand and are now a pest of woollen carpets and fabrics in this country. The use of detector dogs can help with earlier discovery and identification of infested areas and thus reduce the use of pesticides. Sixteen harrier hounds were available for this study, however only six dogs were selected for the actual trials after initial training. There were four trials, in which the dogs had to detect four different stimuli (dog food A, carpet beetle larvae, cockroaches and dog food B). Each run evaluated whether the dog could identify the target pottle out of six pottles. The other five pottles were empty. A dog completed six runs each day over five days for food A and over three days for the other three stimuli. Therefore there were a total of 30 runs for food A and 18 runs for the rest of the stimuli. A run was considered successful when the dog found the target pottle on the first try (i.e. -

Dermestids in Southern Australia

Thursday, 28 June 2018 Nancy Cunningham SARDI Entomology Unit—8429 0933 Dermestids in Southern Australia Dermestid beetles, commonly known as carpet or skin beetles, belong to the family Dermestidae and are common insect scavengers that feed on dry animal or plant material. The Trogoderma genus of Dermestidae are known pests of stored grain and Trogoderma granarium— the khapra beetle— not present in Australia— is listed in the top 100 Global Invasive Species Database (2004). An incursion of this exotic species into Australia could mean severe economic losses and market access issues for producers. It is important that we are able to clearly identify the differences between the various commonly found dermestids, including our native Trogoderma species and the exotic khapra beetle. This fact sheet aims to show the major differences between Dermestidae genera found in South Australia and to discuss the differences between common dermestids and some of our native Trogoderma species as well as pest/exotic species that are not found in Australia. 3mm 7mm Figure 1: Dermestidae Adult Figure 2: Dermestidae Larvae Key features of Dermestidae Vary in size between 1-12mm Adults (Figure 1) Larvae (Figure 2) Oval shaped bodies Numerous setae and ‘hairy’ or ‘fluffy’ appearance Covered in scales or setae (Genus dependent) Obvious head capsule with chewing mouthparts Clubbed antennae often situated within a ‘groove’ Well developed legs on the underside of the head cavity Often found on dried commodities/foodstuff Research supported through: South -

Journal of TSAE Vol. Xx No. X (Xxxx), Xxx–Xxx

11th International Working Conference on Stored Product Protection Session 7 : Museum Pests The use of thermal control against insect pests of cultural property Strang, T.J.K.*# Canadian Conservation Institute, Department of Canadian Heritage, 1030 Innes Rd. Ottawa, ON, Canada, K1B4S7 *Corresponding author, Email: [email protected] #Presenting author, Email: [email protected] DOI: 10.14455/DOA.res.2014.110 Abstract Collections in cultural institutions are vulnerable to many deleterious events. Insects of concern are a blend of ‗household pests‘, typified by clothes moth and dermestid species, ‗timber pests‘ such as anobiid and lyctid species and ‗food pests‘ of kitchen, pantry and granary as collections are quite varied in their composition across museum, archive, library, gallery, historic properties and cultural centers. There is a distribution of scale of museums and concomitant resources to apply against all modes of deterioration, as well as accomplishing operational goals using the collections as a core resource. There is a strong need for museum pest control methods inside an integrated pest management framework to be efficacious, have minimal effect on objects, and be economical in their costs. Through the 1980‘s and 90‘s museum staff became increasingly knowledgeable about industrial hygiene, harmful substances used in preparation methods, preservative solutions and residual insecticides. Some collections have been tested for residual arsenic, mercury, DDT, and other contaminants. Fumigants were curtailed for health and environmental impact so ethylene oxide (ETO), phosphine and methyl bromide (MeBr) followed the loss of grain fumigants which had been applied as liquids in museum storage cabinets. Thermal and controlled atmosphere methods offered a way forward for many museums which found they could not continue previous practices for controlling insects on and inside their objects. -

(Khapra Beetle) and on Its Associated Bacteria

EFFECTS OF EXTREME TEMPERATURES ON THE SURVIVAL OF THE QUARANTINE STORED-PRODUCT PEST, TROGODERMA GRANARIUM (KHAPRA BEETLE) AND ON ITS ASSOCIATED BACTERIA DIANA MARIA WILCHES CORREAL Bachelor of Science in Biology, Los Andes University, 2011 Bachelor of Science in Microbiology, Los Andes University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Biological Sciences University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA ©Diana Maria Wilches Correal, 2016 EFFECTS OF EXTREME TEMPERATURES ON THE SURVIVAL OF THE QUARANTINE STORED-PRODUCT PEST, TROGODERMA GRANARIUM (KHAPRA BEETLE) AND ON ITS ASSOCIATED BACTERIA DIANA MARIA WILCHES CORREAL Date of Defence: November 25/2016 Dr. Robert Laird Associate Professor Ph.D. Co-supervisor Dr. Kevin Floate Research Scientist Ph.D. Co-supervisor Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Lethbridge, Alberta Dr. Paul Fields Research Scientist Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Winnipeg, Manitoba Dr. Theresa Burg Associate Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Mukti Ghimire Plant Health Safeguarding Ph.D. U.S. Department of Agriculture Specialist Seattle, Washington Dr. Tony Russell Assistant Professor Ph.D. Chair ABSTRACT Trogoderma granarium is a pest of stored-grain products in Asia and Africa, and a quarantine pest for much of the rest of the world. To evaluate extreme temperatures as a control strategy for this pest, I investigated the effect of high and low temperatures on the survival (Chapters 2 and 3) and on the microbiome (Chapter 4) of T. granarium. The most cold- and heat-tolerant life stages were diapausing-acclimated larvae and diapausing larvae, respectively. -

Of the World with a Catalogue of All Known Species

POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK INSTYTUT ZOOLOGICZNY ANNALES ZOOLOGICI Tom XXVI Warszawa, 15 XI 1968 Nr 3 M aciej MROCZKOWSKI Distribution of the Dermestidae (Coleoptera) of the World with a Catalogue of all known Species Rozmieszczenie Dermestidae (Coleoptera) na świecie wraz z katologiem wszystkich znanych gatunków РаспространениеDermestidae (Coleoptera) в мире и каталог всех известных видов With 12 maps iismttî http://rcin.org.plPoli <ац|{ О о с с fibLiüIüüA POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK INSTYTUT ZOOLOGICZNY ANNALES ZOOLOGIC1 Tom XXVI Warszawa, 15 XI 1968 Nr 3 Maciej Mroczkowski Distribution of the Dermestidae (Coleoptera) of the World with a Catalogue of all known Species Rozmieszczenie Dermestidae (Coleoptera) na świecie wraz z katalogiem wszystkich znanych gatunków РаспространениеDermestidae ( Coleoptera) в мире и каталог всех известных видов [With 12 maps] CONTENTS Introduction.............................................................................................................................................................. 16 Remarks on the Arrangement of the C atalogue............................................................................................ 17 I. Distribution of the Dermestidae of the World.......................................................................... 17 The Neotropical R egion............................................................................................................................ 19 The Australian R e g io n ............................................................................................................................ -

Biology and Systematics of Trogoderma Species with Special

School of Biomedical Science Biology and Systematics of Trogoderma species with Special Reference to Morphological and Molecular Diagnostic Techniques for Identification of Trogoderma pest species Mark A Castalanelli This thesis is presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University of Technology February 2011 Declaration To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: Date: i Acknowledgments Special thanks to the Cooperative Research Centre for National Plant Biosecurity for their support: Dr Simon McKirdy, Dr Kirsty Bayliss and Dr David Eagling. Kirsty you have been a great coordinator of the education stream, I appreciate the support and organisation of the yearly events across Australia. Simon McKirdy your passion for biosecurity has provided a strong backbone for the future of biosecurity in this country; let’s hope the second rebid is successful. One of the most important groups that need to be thanked are my colleagues from Curtin University, for three years this was my home away from home: Prof David Groth, Dr Kylie Munyard, Dr Keith Gregg, Danielle Giustiniano, Sharon Siva, Mel Corbett, Carla Zammit, Dr Chee Yang Lee, Jason Legder, Ryan Harris, Tash Feeley, Jaden Elphick, Rhys Cransberg, Laurton McGurk, Ibrahim Marzouqi, Rob Walker and Rob Steuart. David thank you for taking on this project when it was just an infant idea and turning it in to one of the most successful projects to come out of the CRC for National Plant Biosecurity, providing positive feedback, pushing to publish and always wanting to have a chat in the lab. -

Identifying Insect Pests in Museums and Heritage Buildings

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325180755 Identifying insect pests in museums and heritage buildings Book · May 2018 CITATIONS READS 0 10,362 1 author: David G. Notton Natural History Museum, London 120 PUBLICATIONS 225 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Hymenoptera fauna of Britain and Ireland View project Systematics of world Diaprioidea View project All content following this page was uploaded by David G. Notton on 17 May 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. David G. Notton Department of Life Sciences, Insects Division, Darwin Centre - room 315, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, United Kingdom. [email protected]. Suggested citation: Notton, D.G. 2018. Identifying insect pests in museums and heritage buildings. 2nd Edition. The Natural History Museum, London. Copyright The Natural History Museum, 2018. Contents Introduction to pest identification.......................................................................................................1 Quick photographic reference for pest beetles, beetle larvae and moths..............................................2 Beetle pests and environmental indicators........................................................................................10 Carpet beetles Australian carpet beetle - Anthrenocerus australis .................................................................................11