William M. Simons 2009.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hank-Aaron.Pdf

The Swing that Rewrote HISTORY 40 years later, Hank Aaron’s feat stands the test of time By Adam DeCock he Braves April 8th home opener marked more than just the the Boston Red Sox, then spent the majority of his well-documented start of the baseball season this year. It also marked the career with the New York Yankees. ‘The Curse of the Bambino’ might 40th anniversary of Hank Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s long be the most well-known curse in baseball, having haunted the Sox standing home run record and #715. for over 80 seasons following the trade that put Ruth in pinstripes. When Aaron stepped into the batter’s box in the fourth inning in a Almost 40 years after Ruth’s 714th home run, an unassuming game against the Los Angeles Dodgers on April 8, 1974, ‘Hammerin’ young ballplayer from Mobile, AL entered the picture. Little did Hank’ did more than break a record that had stood for nearly 40 Aaron know his feat would capture his and future generations of years. The feat itself remains a marvel in baseball history, but is baseball fans, and change the landscape of America’s pastime just one aspect of what makes Aaron’s path as a player, as well as forever. his post-playing days, a memorable journey. And it wasn’t all luck. Aaron ended the 1973 season with 713 home runs, one shy of the “I’m proud of all of my accomplishments that I’ve had in baseball,” record set by Babe Ruth in 1935, a record that most considered Aaron said. -

CHICAGO JEWISH HISTORY Spring Reviews & Summer Previews

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 41, No. 2, Spring 2017 1977 40 2017 chicago jewish historical societ y CHICAGO JEWISH HISTORY Spring Reviews & Summer Previews Sunday, August 6 “Chicago’s Jewish West Side” A New Bus Tour Guided by Jacob Kaplan and Patrick Steffes Co-founders of the popular website www.forgottenchicago.com Details and Reservation Form on Page 15 • CJHS Open Meeting, Sunday, April 30 — Sunday, August 13 Professor Michael Ebner presented an illustrated talk “How Jewish is Baseball?” Report on Page 6 A Lecture by Dr. Zev Eleff • CJHS Open Meeting, Sunday, May 21 — “Gridiron Gadfly? Mary Wisniewski read from her new biography Arnold Horween and of author Nelson Algren. Report on Page 7 • Chicago Metro History Fair Awards Ceremony, Jewish Brawn in Sunday, May 21 — CJHS Board Member Joan Protestant America” Pomaranc presented our Chicago Jewish History Award to Danny Rubin. Report on Page 4 Details on Page 11 2 Chicago Jewish History Spring 2017 Look to the rock from which you were hewn CO-PRESIDENT’S CO LUMN chicago jewish historical societ y The Special Meaning of Jewish Numbers: Part Two 2017 The Power of Seven Officers & Board of In honor of the Society's 40th anniversary, in the last Directors issue of Chicago Jewish History I wrote about the Jewish Dr. Rachelle Gold significance of the number 40. We found that it Jerold Levin expresses trial, renewal, growth, completion, and Co-Presidents wisdom—all relevant to the accomplishments of the Dr. Edward H. Mazur* Society. With meaningful numbers on our minds, Treasurer Janet Iltis Board member Herbert Eiseman, who recently Secretary completed his annual SAR-EL volunteer service in Dr. -

July/August 2021/5781 President’S Message - Kelli Caplan It’S Summer and the UJC Is Alive with the Sound of Camp! All Wed to the UJC for Different Reasons

Dog Days of In the Box Series: Cooking with Summer Beach in a Box Carmela: Challah Page 4 Page 11 Page 19 News of the Jewish VA Peninsula Community July/August 2021/5781 President’s Message - Kelli Caplan It’s summer and the UJC is alive with the sound of camp! all wed to the UJC for different reasons. It Oh, how glorious it is to see and hear our youth having was fantastic to see such a gathering, and such a wonderful time at Camp Chaverim. Waching the drove home the importance of what we UJC come to life again with tie-dye clad children sporting do. What everyone had in common that huge smiles can boost anyone’s mood. It’s day was a smile and an life returning to normal, just what we all appreciation for our center and its ongoing needed. effort to improve year after year. Camp is just one way that the UJC has At the annual meeting, we also recognized shone brightly this year. We have worked an impressive number of volunteers. We hard to ensure that we stayed connected have a virtual army of members willing to during the past year. And it has worked. step up and help out when needed. That The energy at the UJC is as robust as ever. army powers our progress and deepens There are so many facets of life here that our connections. Without our volunteers, have blossomed in the face of adversity. we are like an octopus without tentacles. They add to all that we do, and brighten Our outreach and programming has our light out in the community. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

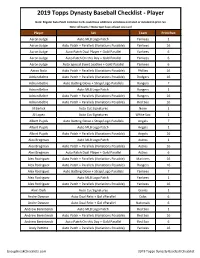

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player

2019 Topps Dynasty Baseball Checklist - Player Note: Regular Auto Patch Common Cards could have additional variations not listed or included in print run Note: All teams + None Spot have at least one card Player Set Team Print Run Aaron Judge Auto MLB Logo Patch Yankees 1 Aaron Judge Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Yankees 16 Aaron Judge Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Patch On this Day + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Judge Auto Special Event Leather + Gold Parallel Yankees 6 Aaron Nola Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Phillies 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Dodgers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Rangers 7 Adrian Beltre Auto MLB Logo Patch Rangers 1 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Adrian Beltre Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Red Sox 16 Al Barlick Auto Cut Signatures None 1 Al Lopez Auto Cut Signatures White Sox 1 Albert Pujols Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Angels 7 Albert Pujols Auto MLB Logo Patch Angels 1 Albert Pujols Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Angels 16 Alex Bregman Auto MLB Logo Patch Astros 1 Alex Bregman Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Astros 16 Alex Bregman Auto Patch Dual Player + Gold Parallel Astros 6 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Mariners 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Patch + Parallels (Variations Possible) Rangers 16 Alex Rodriguez Auto Batting Glove + Strap/Logo Parallels Yankees 7 Alex Rodriguez -

April Acquiring a Piece of Pottery at the Kidsview Seminars

Vol. 36 No. 2 NEWSLETTER A p r i l 2 0 1 1 Red Wing Meetsz Baseball Pages 6-7 z MidWinter Jaw-Droppers Page 5 RWCS CONTACTS RWCS BUSINESS OFFICE In PO Box 50 • 2000 Old West Main St. • Suite 300 Pottery Place Mall • Red Wing, MN 55066-0050 651-388-4004 or 800-977-7927 • Fax: 651-388-4042 This EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: STACY WEGNER [email protected] ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT: VACANT Issue............. [email protected] Web site: WWW.RedwINGCOLLECTORS.ORG BOARD OF DIRECTORS Page 3 NEWS BRIEFS, ABOUT THE COVER PRESIDENT: DAN DEPASQUALE age LUB EWS IG OUndaTION USEUM EWS 2717 Driftwood Dr. • Niagara Falls, NY 14304-4584 P 4 C N , B RWCS F M N 716-216-4194 • [email protected] Page 5 MIDWINTER Jaw-DROPPERS VICE PRESIDENT: ANN TUCKER Page 6 WIN TWINS: RED WING’S MINNESOTA TWINS POTTERY 1121 Somonauk • Sycamore, IL 60178 Page 8 MIDWINTER PHOTOS 815-751-5056 • [email protected] Page 10 CHAPTER NEWS, KIDSVIEW UPdaTES SECRETARY: JOHN SAGAT 7241 Emerson Ave. So. • Richfield, MN 55423-3067 Page 11 RWCS FINANCIAL REVIEW 612-861-0066 • [email protected] Page 12 AN UPdaTE ON FAKE ADVERTISING STOnewaRE TREASURER: MARK COLLINS Page 13 BewaRE OF REPRO ALBANY SLIP SCRATCHED MINI JUGS 4724 N 112th Circle • Omaha, NE 68164-2119 Page 14 CLASSIFIEDS 605-351-1700 • [email protected] Page 16 MONMOUTH EVENT, EXPERIMENTAL CHROMOLINE HISTORIAN: STEVE BROWN 2102 Hunter Ridge Ct. • Manitowoc, WI 54220 920-684-4600 • [email protected] MEMBERSHIP REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE: RUSSA ROBINSON 1970 Bowman Rd. • Stockton, CA 95206 A primary membership in the Red Wing Collectors Society is 209-463-5179 • [email protected] $25 annually and an associate membership is $10. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Padres Press Clips Wednesday, February 22, 2017

Padres Press Clips Wednesday, February 22, 2017 Article Source Author Page Former Padres reliever Akinori Otsuka to serve UT San Diego Lin 2 as Triple-A bullpen coach Manfred, Clark tussling over rule change proposals UT San Diego Sanders 4 Padres' Jon Edwards looking forward to healthy spring UT San Diego Lin 6 Padres' 32-player ping pong tournament had a Cut 4/MLB.com Cassavell 8 'championship game atmosphere' from the start Padres considering new way to use SP depth MLB.com Cassavell 9 Rule 5 picks have legit shot of making Padres MLB.com Cassavell 10 Padres set with current crop of players MLB.com Cassavell 12 1 Former Padres reliever Akinori Otsuka to serve as Triple-A bullpen coach BY: DENNIS LIN San Diego Union Tribune February 21, 2017 A few beads of sweat were still visible on Akinori Otsuka’s face as he stood in the shade of the bullpen area at the Peoria Sports Complex. The same, wide smile that endeared him to teammates, coaches and fans across two continents was more obvious. “This is for my growth and experience,” Otsuka said Tuesday. “This is my challenge, to become a major league coach. And I want to help the players. Everybody helped me a lot when I was a player, so now I want to give back.” Otsuka, who pitched for the Padres from 2004-05, has returned to the organization with an unprecedented title: Triple-A El Paso’s bullpen coach. The job, created over the winter, brought the gregarious right-hander back to San Diego’s spring-training site over the weekend. -

Jim Bouton's Ball Four Changes Baseball's Image

Undergraduate Review Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 8 1986 Myth and America's National Pastime: Jim Bouton's Ball Four Changes Baseball's Image Steven B. Stone '86 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/rev Recommended Citation Stone '86, Steven B. (1986) "Myth and America's National Pastime: Jim Bouton's Ball Four Changes Baseball's Image," Undergraduate Review: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/rev/vol1/iss1/8 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Stone '86: Myth and America's National Pastime: Jim Bouton's Ball Four Chan Fugitive in Brink's Case," NIT, May 25, :night-Ridder Newspapers), Holmesburg 'he New York Review of Books, Sept. 22, Myth and America's National Pastime: Jim Bouton's BaH Four Changes Baseball's Image Steven B. Stone IAIsweek, July 21, 1980, p. 35. lewsweek, Dec. 15, 1980, p. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3. -

The Center at Camden CC Connector Building, Room 103 Camden County College PO Box 200 the Center Blackwood, NJ 08012

“Where we share the world with you.” The Center at Camden CC Connector Building, Room 103 Camden County College PO Box 200 The Center Blackwood, NJ 08012 Director: John L. Pesda at Camden County College www.camdencc.edu/civiccenter SPRING 2018 | Program Brochure Mission he Center at Camden County College focuses Ton the needs and interests of educators and the community at large. Its goal is to create an informed citizenry through exploration of humanities, social John L. Pesda sciences, natural sciences and issues critical to a democratic society. Citizens have the opportunity Director to meet scholars, scientists, government officials and business leaders to explore historical and current issues and discuss societal problems and their solutions Open Admissions Policy All members of the community are welcome to attend our courses, special events and lecture series. Minors may attend, preferably if accompanied by a registered parent or guardian. About Us Ellen Hernandez The Center offers interesting and thought-provoking Associate Director courses and events to help teachers to meet their professional development requirements and community members to enhance their knowledge. Registrants may choose to attend one or more sessions of any series or course. Registration In order for us to notify you of any cancellations or changes, all participants are asked to register prior to attending. We reserve the right to cancel or reschedule programs should the need arise. Please check our website for cancellations, Valerie Concordia changes, and other updates. Project Coordinator Contact Information MAILING ADDRESS: THE CENTER AT CAMDEN CC, CAMDEN COUNTY COLLEGE, PO BOX 200, BLACKWOOD, NJ 08012 OFFICE: MADISON CONNECTOR 103, MAIN CAMPUS (BLACKWOOD) PHONE: (856) 227-7200, EXT.