The Christian Character of Tolkien's Invented World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythlore Index Plus

MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS MYTHLORE ISSUES 1–137 with Tolkien Journal Mythcon Conference Proceedings Mythopoeic Press Publications Compiled by Janet Brennan Croft and Edith Crowe 2020. This work, exclusive of the illustrations, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Tim Kirk’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with his kind permission. Sarah Beach’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with her kind permission. Copyright Sarah L. Beach 2007. MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS An Index to Selected Publications of The Mythopoeic Society MYTHLORE, ISSUES 1–137 TOLKIEN JOURNAL, ISSUES 1–18 MYTHOPOEIC PRESS PUBLICATIONS AND MYTHCON CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS COMPILED BY JANET BRENNAN CROFT AND EDITH CROWE Mythlore, January 1969 through Fall/Winter 2020, Issues 1–137, Volume 1.1 through 39.1 Tolkien Journal, Spring 1965 through 1976, Issues 1–18, Volume 1.1 through 5.4 Chad Walsh Reviews C.S. Lewis, The Masques of Amen House, Sayers on Holmes, The Pedant and the Shuffly, Tolkien on Film, The Travelling Rug, Past Watchful Dragons, The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America, Perilous and Fair, and Baptism of Fire Narnia Conference; Mythcon I, II, III, XVI, XXIII, and XXIX Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Janet Brennan Croft .....................................................................................................................................1 -

LOTR and Beowulf: I Need a Hero

Jestice/English 4 Lord of the Rings and Beowulf: I need a hero! (100 points) Directions: 1. On your own paper, and as you watch the selected scenes, answer the following questions by comparing and contrasting the heroism of Frodo Baggins to that of Beowulf. (The scene numbers are from the extended version; however, the scene titles are consistent with the regular edition.) 2. Use short answer but complete sentences. Fellowship of the Ring Scene 10: The Shadow of the Past Gandalf already has shown Frodo the One Ring and has told Frodo he must keep it hidden and safe. Frodo obliges. But when Gandalf tells him the story of the ring and that Frodo must take it out of the Shire, Frodo’s reaction is different. 1. Explain why Frodo reacts the way he does. Is this behavior fitting for a hero? Why or why not? Is Frodo a hero at this point of the story? 2. How does this differ from Beowulf’s call to adventure? Scene 27: The Council of Elrond Leaders from across Middle Earth have gathered in the Elvish capital of Rivendell to discuss the fate of the One Ring. Frodo has taken the ring to Rivendell for safekeeping. Having already tried unsuccessfully to destroy the ring, the leaders argue about who should take it to be consumed in the fires of Mordor. Frodo steps forward and accepts the challenge. 1. Frodo’s physical stature makes this journey seem impossible. What kinds of traits apparent so far in the story will help him overcome this deficiency? 2. -

A Secret Vice: the Desire to Understand J.R.R

Mythmoot III: Ever On Proceedings of the 3rd Mythgard Institute Mythmoot BWI Marriott, Linthicum, Maryland January 10-11, 2015 A Secret Vice: The Desire to Understand J.R.R. Tolkien’s Quenya Or, Out of the Frying-Pan Into the Fire: Creating a Realistic Language as a Basis for Fiction Cheryl Cardoza In a letter to his son Christopher in February of 1958, Tolkien said “No one believes me when I say that my long book is an attempt to create a world in which a form of language agreeable to my personal aesthetic might seem real” (Letters 264). He added that The Lord of the Rings “was an effort to create a situation in which a common greeting would be elen síla lúmenn’ omentielmo,1 and that the phrase long antedated the book” (Letters 264-5). Tolkien often felt guilty about this, his most secret vice. Even as early as 1916, he confessed as much in a letter to Edith Bratt: “I have done some touches to my nonsense fairy language—to its improvement. I often long to work at it and don’t let myself ‘cause though I love it so, it does seem a mad hobby” (Letters 8). It wasn’t until his fans encouraged him, that Tolkien started to 1 Later, Tolkien decided that Frodo’s utterance of this phrase was in error as he had used the exclusive form of we in the word “omentielmo,” but should have used the inclusive form to include Gildor and his companions, “omentielvo.” The second edition of Fellowship reflected this correction despite some musings on leaving it to signify Frodo being treated kindly after making a grammatical error in Quenya (PE 17: 130-131). -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Middle-Earth: the Wizards Characters(Hero) Resources(Hero

Middle-earth: The Wizards Card-list (484 cards) Sold in starters and boosters (no cards from other sets needed to play). A booster (15 cards, 36 boosters per display) holds 1 rare, 3 uncommons, and 11 commons. A starter holds a fixed set (at random), 3 rares, 9 uncommons, and 40 commons. R: rare; U: uncommon; CA1: once on general common sheet; CA2: twice on general common sheet; CB1: once on booster-only common sheet; CB2: twice on booster-only common sheet; F#: in # different fixed sets (out of 5). Look at the Fixed pack specs to see what cards are in in which fixed set. Characters (hero) Thorin II R Gwaihir R Risky Blow CA Thranduil F1 Halfling Stealth CB2 Roäc the Raven R Adrazar F1 Vôteli CB Halfling Strength CB2 Sacrifice of Form R Alatar F2 Vygavril R Hauberk of Bright Mail CA Sapling of the White Tree U Anborn U Wacho U Healing Herbs CA2 Scroll of Isildur U Annalena F2 Hiding R Secret Entrance R Aragorn II F1 Resources (hero) Hillmen U Secret Passage CA Arinmîr U A Chance Meeting CB Hobbits R Shadowfax R Arwen R A Friend or Three CB2 Horn of Anor CB Shield of Iron-bound Ash CA2 Balin U Align Palantir U Horses CA Skinbark R Bard Bowman F2 Anduin River CB2 Iron Hill Dwarves F1 Southrons R Barliman Butterbur U Anduril R Kindling of the Spirit CA Star-glass U Beorn F1 Army of the Dead R Knights of Dol Amroth U Stars U Beregond F1 Ash Mountains CB Lapse of Will U Stealth CA Beretar U Athelas U Leaflock U Sting U Bergil U Beautiful Gold Ring CA2 Lesser Ring U Stone of Erech R Bifur CB Beornings F1 Lordly Presence CB2 Sun U Bilbo R Bill -

How Many Strides from Hobbiton to Mordor?

Journal of Interdisciplinary Science Topics How many strides from Hobbiton to Mordor? Tabitha Watson The Centre for Interdisciplinary Science, University of Leicester 18/04/2018 Abstract This paper uses ratios in order to determine the number of strides an average sized hobbit would have to take to complete the journey from Hobbiton to Mount Doom. It was found that an average human male is approximately 1.7 times taller than the average hobbit, making a hobbit’s stride length around 46 centimetres. This value was then applied to the distance between the start and end points of the quest, showing that the hobbit would be required to take a grand total of 4870433 strides to complete the journey. Introduction Journey Start and Distance Mode of The plot of The Lord of the Rings, a popular fantasy Part End Points (km) Transport trilogy, centres on a Hobbit’s quest to destroy the Hobbiton to 1 737.08 Foot ‘One Ring’, Sauron’s tool of evil dominion, in the fires Rivendell of Mount Doom [1]. This paper aims to determine Rivendell to 2 743.52 Foot how many strides the titular hobbit, Frodo Baggins, Lothlorien would need to have taken to travel from his home in Lothlorien Hobbiton all the way to Mordor, the location of 3 to Rauros 626.04 Boat Mount Doom. Falls Rauros Falls Theory 4 to Mount 756.39 Foot Hobbits, also known as halflings, are a fictional race Doom of diminutive humanoids which inhabit J.R.R Tolkien’s Table 1 – The four main parts of the journey realm of Middle Earth. -

Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc Anderson Rearick Mount Vernon Nazarene University

Inklings Forever Volume 4 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fourth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Article 10 Lewis & Friends 3-2004 Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc Anderson Rearick Mount Vernon Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rearick, Anderson (2004) "Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc," Inklings Forever: Vol. 4 , Article 10. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol4/iss1/10 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume IV A Collection of Essays Presented at The Fourth FRANCES WHITE EWBANK COLLOQUIUM ON C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2004 Upland, Indiana Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? Anderson Rearick, III Mount Vernon Nazarene University Rearick, Anderson. “Why Is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc?” Inklings Forever 4 (2004) www.taylor.edu/cslewis 1 Why is the Only Good Orc a Dead Orc? Anderson M. Rearick, III The Dark Face of Racism Examined in Tolkien’s themselves out of sync with most of their peers, thus World1 underscoring the fact that Tolkien’s work has up until recently been the private domain of a select audience, In Jonathan Coe’s novel, The Rotters’ Club, a an audience who by their very nature may have confrontation takes place between two characters over inhibited serious critical examinations of Tolkien’s what one sees as racist elements in Tolkien’s Lord of work. -

Small Renaissances Engendered in JRR Tolkien's Legendarium

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2017 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Dominic DiCarlo Meo Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meo, Dominic DiCarlo, "'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 555. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/555 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Abstract After surviving the trenches of World War I when many of his friends did not, Tolkien continued as the rest of the world did: moving, growing, and developing, putting the darkness of war behind. He had children, taught at the collegiate level, wrote, researched. Then another Great War knocked on the global door. His sons marched off, and Britain was again consumed. The "War to End All Wars" was repeating itself and nothing was for certain. In such extended dark times, J. R. R. Tolkien drew on what he knew-language, philology, myth, and human rights-peering back in history to the mythologies and legends of old while igniting small movements in modern thought. Arthurian, Beowulfian, African, and Egyptian myths all formed a bedrock for his Legendarium, and fantasy-fiction as we now know it was rejuvenated.Just like the artists, authors, and thinkers from the Late Medieval period, Tolkien summoned old thoughts to craft new creations that would cement themselves in history forever. -

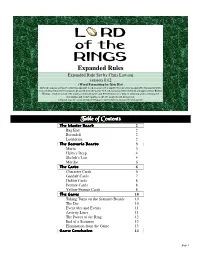

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson Version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) the Following Is a Rewrite of the Existing Rule Book

L RD of the RINGS Expanded Rules Expanded Rule Set by Chris Lawson version 0.62 (Word Formatting by Idris Hsi) The following is a rewrite of the existing rule book. It is not yet complete but the sections included explain the rules in more detail than the existing set provided with the game. The following has been checked and approved by Reiner Knizia. (Author’s note: My thanks to Chris Bowyer and Reiner Knizia for help in checking and correcting the documents and to the citizens of the rec.games.board.newsgroup. Original may be found at http://freespac e.virgin.net/chris.lawson/rk/lotr/faq.htm Table of Contents The Master Board 2 Bag End 2 Rivendell 2 Lothlórien 2 The Scenario Boards 3 Moria 3 Helm’s Deep 4 Shelob’s Lair 5 Mordor 6 The Cards 6 Character Cards 6 Gandalf Cards 7 Hobbit Cards 8 Feature Cards 8 Yellow Feature Cards 8 The G am e 10 Taking Turns on the Scenario Boards 10 The Die 10 Event tiles and Events 11 Activity Lines 11 The Power of the Ring 12 End of a Scenario 13 Elimination from the Game 13 G am e Conclusion 14 Page 1 T he M aster Board The master board shows three locations (Bag End, Rivendell and Lothlórien) and four scenarios (Moria, Helm’s Deep, Shelob’s Lair and Mordor). selects a card from hand and passes it to the player on the left. Bag End This continues until everyone has received and passed on one The game starts at Bag End. -

The Hidden Meaning of the Lord of the Rings the Theological Vision in Tolkien’S Fiction

LITERATURE The Hidden Meaning of The Lord of the Rings The Theological Vision in Tolkien’s Fiction Joseph Pearce LECTURE GUIDE Learn More www.CatholicCourses.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Lecture Summaries LECTURE 1 Introducing J.R.R. Tolkien: The Man behind the Myth...........................................4 LECTURE 2 True Myth: Tolkien, C.S. Lewis & the Truth of Fiction.............................................8 Feature: The Use of Language in The Lord of the Rings............................................12 LECTURE 3 The Meaning of the Ring: “To Rule Them All, and in the Darkness Bind Them”.......................................14 LECTURE 4 Of Elves & Men: Fighting the Long Defeat.................................................................18 Feature: The Scriptural Basis for Tolkien’s Middle-earth............................................22 LECTURE 5 Seeing Ourselves in the Story: The Hobbits, Boromir, Faramir, & Gollum as Everyman Figures.......... 24 LECTURE 6 Of Wizards & Kings: Frodo, Gandalf & Aragorn as Figures of Christ..... 28 Feature: The Five Races of Middle-earth................................................................................32 LECTURE 7 Beyond the Power of the Ring: The Riddle of Tom Bombadil & Other Neglected Characters....................34 LECTURE 8 Frodo’s Failure: The Triumph of Grace......................................................................... 38 Suggested Reading from Joseph Pearce................................................................................42 2 The Hidden Meaning -

Gandalf: One Wizard to Lead Them, One to Find Them, One to Bring Them And, Despite the Darkness, Unite Them

Mythmoot III: Ever On Proceedings of the 3rd Mythgard Institute Mythmoot BWI Marriott, Linthicum, Maryland January 10-11, 2015 Gandalf: One Wizard to lead them, one to find them, one to bring them and, despite the darkness, unite them. Alex Gunn Middle Earth is a wonderful but strangely familiar place. The Hobbits, Elves, Men and other peoples who live in caves, forests, mountain ranges and stone cities, are all combined by Tolkien to create a fantasy world which is full of wonder, beauty and magic. However, looking past these fantastical elements, we can see that Middle Earth has many similarities to the society in which we live. The different races of Middle Earth have distinct and deep differences and often keep themselves separate from one another because of mutual distrust or dislike. Due to these divisions, only one person, one who does not belong to any particular race or people, can unite them for the coming war: Gandalf the Wizard who embodies the qualities needed to be an effective leader in our world. As Sue Kim points out in her book Beyond black and White: Race and Postmodernism in Lord of the Rings, Tolkien himself declared that, “the desire to converse with other living things is one of the great allurements of fantasy” (Kim 555). Given this belief, it is no surprise that Tolkien,‘fills his imagined worlds with a plethora of intelligent non human races and exotic ethnicities, all changing over time: Elves, Dwarves, Men, Hobbits, Ents, Trolls, Orcs, Wild Men, talking beasts and embodied spirits’ (Kim 555). This plethora, as Kim puts it, makes Gandalf an important literary tool for Tolkien because to believe that such a varied mix of people, creatures, races and ethnicities live in complete harmony would feel false and perhaps too convenient. -

Boromir's Defense Mechanism in Lord of the Rings

BRIGHT: A Journal of English Language Teaching, Linguistics, and Literature Vol. 3 No. 2, 2020 pp. 23-32 E-ISSN: 2599-0322 Boromir’s Defense Mechanism in Lord of The Rings: Fellowship of The Ring Sukma Eka Satya Ginalih [email protected] Universitas Komputer Indonesia Nungki Heriyati [email protected] Universitas Komputer Indonesia ABSTRACT The objective of this research is to analyze Boromir’s defense mechanism and his characterization. This research applies several theory and method which encompasses characterization, psychoanalysis, and defense mechanisms. It is also aims to examine the types of defense mechanism used by the character. Data are collected from scenes of the film, dialogues, gestures, responses and facial expressions of the character. The field of the study are around the scene of the films of which the character appeared. Some limited history are also studied, collected from the film and biography from other sources. The result of the research shows that the character is considered as a representation of psychological state of human being. It shows the way human defend him/herself when facing problem. In the analysis, the character uses several defense mechanisms which is Reaction formation, Denial, and Displacement that made the character resist the tempation to harm his companion and being reckless. Keywords: characterization, psychoanalysis, defense mechanism. INTRODUCTION Lord of The Rings is an epic fantasy novel written by J.R.R. Tolkien. As the sequel to the first novel, The Hobbits, Lord of The Rings tells about the journey of Frodo Baggins which is Bilbo’s nephew to vanquish Sauron’s ring.