Red Dwarfs and the End of the Main Sequence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Dwarfs

Chandra X-Ray Observatory X-Ray Astronomy Field Guide White Dwarfs White dwarfs are among the dimmest stars in the universe. Even so, they have commanded the attention of astronomers ever since the first white dwarf was observed by optical telescopes in the middle of the 19th century. One reason for this interest is that white dwarfs represent an intriguing state of matter; another reason is that most stars, including our sun, will become white dwarfs when they reach their final, burnt-out collapsed state. A star experiences an energy crisis and its core collapses when the star's basic, non-renewable energy source - hydrogen - is used up. A shell of hydrogen on the edge of the collapsed core will be compressed and heated. The nuclear fusion of the hydrogen in the shell will produce a new surge of power that will cause the outer layers of the star to expand until it has a diameter a hundred times its present value. This is called the "red giant" phase of a star's existence. A hundred million years after the red giant phase all of the star's available energy resources will be used up. The exhausted red giant will puff off its outer layer leaving behind a hot core. This hot core is called a Wolf-Rayet type star after the astronomers who first identified these objects. This star has a surface temperature of about 50,000 degrees Celsius and is A composite furiously boiling off its outer layers in a "fast" wind traveling 6 million image of the kilometers per hour. -

Revisiting the Pre-Main-Sequence Evolution of Stars I. Importance of Accretion Efficiency and Deuterium Abundance ?

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. Kunitomo_etal c ESO 2018 March 22, 2018 Revisiting the pre-main-sequence evolution of stars I. Importance of accretion efficiency and deuterium abundance ? Masanobu Kunitomo1, Tristan Guillot2, Taku Takeuchi,3,?? and Shigeru Ida4 1 Department of Physics, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 464-8602, Japan e-mail: [email protected] 2 Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, CNRS UMR 7293, 06304 Nice CEDEX 04, France 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8551, Japan 4 Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8551, Japan Received 5 February 2016 / Accepted 6 December 2016 ABSTRACT Context. Protostars grow from the first formation of a small seed and subsequent accretion of material. Recent theoretical work has shown that the pre-main-sequence (PMS) evolution of stars is much more complex than previously envisioned. Instead of the traditional steady, one-dimensional solution, accretion may be episodic and not necessarily symmetrical, thereby affecting the energy deposited inside the star and its interior structure. Aims. Given this new framework, we want to understand what controls the evolution of accreting stars. Methods. We use the MESA stellar evolution code with various sets of conditions. In particular, we account for the (unknown) efficiency of accretion in burying gravitational energy into the protostar through a parameter, ξ, and we vary the amount of deuterium present. Results. We confirm the findings of previous works that, in terms of evolutionary tracks on the Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) diagram, the evolution changes significantly with the amount of energy that is lost during accretion. -

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants There is a large variety of stellar models which have a distinct core – envelope structure. While any main sequence star, or any white dwarf, may be well approximated with a single polytropic model, the stars with the core – envelope structure may be approximated with a composite polytrope: one for the core, another for the envelope, with a very large difference in the “K” constants between the two. This is a consequence of a very large difference in the specific entropies between the core and the envelope. The original reason for the difference is due to a jump in chemical composition. For example, the core may have no hydrogen, and mostly helium, while the envelope may be hydrogen rich. As a result, there is a nuclear burning shell at the bottom of the envelope; hydrogen burning shell in our example. The heat generated in the shell is diffusing out with radiation, and keeps the entropy very high throughout the envelope. The core – envelope structure is most pronounced when the core is degenerate, and its specific entropy near zero. It is supported against its own gravity with the non-thermal pressure of degenerate electron gas, while all stellar luminosity, and all entropy for the envelope, are provided by the shell source. A common property of stars with well developed core – envelope structure is not only a very large jump in specific entropy but also a very large difference in pressure between the center, Pc, the shell, Psh, and the photosphere, Pph. Of course, the two characteristics are closely related to each other. -

Brown Dwarf: White Dwarf: Hertzsprung -Russell Diagram (H-R

Types of Stars Spectral Classifications: Based on the luminosity and effective temperature , the stars are categorized depending upon their positions in the HR diagram. Hertzsprung -Russell Diagram (H-R Diagram) : 1. The H-R Diagram is a graphical tool that astronomers use to classify stars according to their luminosity (i.e. brightness), spectral type, color, temperature and evolutionary stage. 2. HR diagram is a plot of luminosity of stars versus its effective temperature. 3. Most of the stars occupy the region in the diagram along the line called the main sequence. During that stage stars are fusing hydrogen in their cores. Various Types of Stars Brown Dwarf: White Dwarf: Brown dwarfs are sub-stellar objects After a star like the sun exhausts its nuclear that are not massive enough to sustain fuel, it loses its outer layer as a "planetary nuclear fusion processes. nebula" and leaves behind the remnant "white Since, comparatively they are very cold dwarf" core. objects, it is difficult to detect them. Stars with initial masses Now there are ongoing efforts to study M < 8Msun will end as white dwarfs. them in infrared wavelengths. A typical white dwarf is about the size of the This picture shows a brown dwarf around Earth. a star HD3651 located 36Ly away in It is very dense and hot. A spoonful of white constellation of Pisces. dwarf material on Earth would weigh as much as First directly detected Brown Dwarf HD 3651B. few tons. Image by: ESO The image is of Helix nebula towards constellation of Aquarius hosts a White Dwarf Helix Nebula 6500Ly away. -

The Potential of Planets Orbiting Red Dwarf Stars to Support Oxygenic Photosynthesis and Complex Life

1 The Potential of Planets Orbiting Red Dwarf Stars to Support Oxygenic Photosynthesis and Complex Life Joseph Gale1 and Amri Wandel2 The Institute of Life Sciences1and The Racach Institute of Physics2, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 91904, Israel. [email protected] [email protected] Accepted for publication in the International Journal of Astrobiology Abstract We review and reassess the latest findings on the existence of extra-solar system planets and their potential of having environmental conditions that could support Earth-like life. Within the last two decades, the multi-millennial question of the existence of extra-Solar- system planets has been resolved with the discovery of numerous planets orbiting nearby stars, many of which are Earth-sized (and some even with moderate surface temperatures). Of particular interest in our search for clement conditions for extra-solar system life are planets orbiting Red Dwarf (RD) stars, the most numerous stellar type in the Milky Way galaxy. We show that including RDs as potential life supporting host stars could increase the probability of finding biotic planets by a factor of up to a thousand, and reduce the estimate of the distance to our nearest biotic neighbor by up to 10. We argue that multiple star systems need to be taken into account when discussing habitability and the abundance of biotic exoplanets, in particular binaries of which one or both members are RDs. Early considerations indicated that conditions on RD planets would be inimical to life, as their Habitable Zones (where liquid water could exist) would be so close as to make planets tidally locked to their star. -

Chapter 16 the Sun and Stars

Chapter 16 The Sun and Stars Stargazing is an awe-inspiring way to enjoy the night sky, but humans can learn only so much about stars from our position on Earth. The Hubble Space Telescope is a school-bus-size telescope that orbits Earth every 97 minutes at an altitude of 353 miles and a speed of about 17,500 miles per hour. The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) transmits images and data from space to computers on Earth. In fact, HST sends enough data back to Earth each week to fill 3,600 feet of books on a shelf. Scientists store the data on special disks. In January 2006, HST captured images of the Orion Nebula, a huge area where stars are being formed. HST’s detailed images revealed over 3,000 stars that were never seen before. Information from the Hubble will help scientists understand more about how stars form. In this chapter, you will learn all about the star of our solar system, the sun, and about the characteristics of other stars. 1. Why do stars shine? 2. What kinds of stars are there? 3. How are stars formed, and do any other stars have planets? 16.1 The Sun and the Stars What are stars? Where did they come from? How long do they last? During most of the star - an enormous hot ball of gas day, we see only one star, the sun, which is 150 million kilometers away. On a clear held together by gravity which night, about 6,000 stars can be seen without a telescope. -

Pulsating Red Giant Stars in Eccentric Binary Systems Discovered from Kepler Space-Based Photometry a Sample Study and the Analysis of KIC 5006817 P

A&A 564, A36 (2014) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322477 & c ESO 2014 Astrophysics Pulsating red giant stars in eccentric binary systems discovered from Kepler space-based photometry A sample study and the analysis of KIC 5006817 P. G. Beck1,K.Hambleton2,1,J.Vos1, T. Kallinger3, S. Bloemen1, A. Tkachenko1, R. A. García4, R. H. Østensen1, C. Aerts1,5,D.W.Kurtz2, J. De Ridder1,S.Hekker6, K. Pavlovski7, S. Mathur8,K.DeSmedt1, A. Derekas9, E. Corsaro1, B. Mosser10,H.VanWinckel1,D.Huber11, P. Degroote1,G.R.Davies12,A.Prša13, J. Debosscher1, Y. Elsworth12,P.Nemeth1, L. Siess14,V.S.Schmid1,P.I.Pápics1,B.L.deVries1, A. J. van Marle1, P. Marcos-Arenal1, and A. Lobel15 1 Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, KU Leuven, 3001 Leuven, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] 2 Jeremiah Horrocks Institute, University of Central Lancashire, Preston PR1 2HE, UK 3 Institut für Astronomie der Universität Wien, Türkenschanzstr. 17, 1180 Wien, Austria 4 Laboratoire AIM, CEA/DSM-CNRS – Université Denis Diderot-IRFU/SAp, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex, France 5 Department of Astrophysics, IMAPP, University of Nijmegen, PO Box 9010, 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands 6 Astronomical Institute Anton Pannekoek, University of Amsterdam, Science Park 904, 1098 XH Amsterdam, The Netherlands 7 Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 8 Space Science Institute, 4750 Walnut street Suite #205, Boulder CO 80301, USA 9 Konkoly Observ., Research Centre f. Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1121 Budapest, Hungary 10 LESIA, CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Denis Diderot, Observatoire de Paris, 92195 Meudon Cedex, France 11 NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field CA 94035, USA 12 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgebaston, Birmingham B13 2TT, UK 13 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Villanova University, 800 East Lancaster avenue, Villanova PA 19085, USA 14 Institut d’Astronomie et d’Astrophysique, Univ. -

A FEROS Survey of Hot Subdwarf Stars

Open Astron. 2018; 27: 7–13 Research Article Stéphane Vennes*, Péter Németh, and Adela Kawka A FEROS Survey of Hot Subdwarf Stars https://doi.org/10.1515/astro-2018-0005 Received Oct 02, 2017; accepted Nov 07, 2017 Abstract: We have completed a survey of twenty-two ultraviolet-selected hot subdwarfs using the Fiber-fed Extended Range Optical Spectrograph (FEROS) and the 2.2-m telescope at La Silla. The sample includes apparently single objects as well as hot subdwarfs paired with a bright, unresolved companion. The sample was extracted from our GALEX cat- alogue of hot subdwarf stars. We identified three new short-period systems (P = 3.5 hours to 5 days) and determined the orbital parameters of a long-period (P = 62d.66) sdO plus G III system. This particular system should evolve into a close double degenerate system following a second common envelope phase. We also conducted a chemical abundance study of the subdwarfs: Some objects show nitrogen and argon abundance excess with respect to oxygen. We present key results of this programme. Keywords: binaries: close, binaries: spectroscopic, subdwarfs, white dwarfs, ultraviolet: stars 1 Introduction ing a mass transfer event, i.e., comparable to the observed fraction (≈70%) of short period binaries (P < 10 d, Maxted et al. 2001; Morales-Rueda et al. 2003), while the remain- The properties of extreme horizontal branch (EHB) stars, ing single objects are formed by the merger of two helium i.e., the hot, hydrogen-rich (sdB) and helium-rich subd- white dwarfs which would also result in a thin hydrogen warf (sdO) stars, located at the faint blue end of the hori- layer. -

Massive Fast Rotating Highly Magnetized White Dwarfs: Theory and Astrophysical Applications

Massive Fast Rotating Highly Magnetized White Dwarfs: Theory and Astrophysical Applications Thesis Advisors Ph.D. Student Prof. Remo Ruffini Diego Leonardo Caceres Uribe* Dr. Jorge A. Rueda *D.L.C.U. acknowledges the financial support by the International Relativistic Astrophysics (IRAP) Ph.D. program. Academic Year 2016–2017 2 Contents General introduction 4 1 Anomalous X-ray pulsars and Soft Gamma-ray repeaters: A new class of pulsars 9 2 Structure and Stability of non-magnetic White Dwarfs 21 2.1 Introduction . 21 2.2 Structure and Stability of non-rotating non-magnetic white dwarfs 23 2.2.1 Inverse b-decay . 29 2.2.2 General Relativity instability . 31 2.2.3 Mass-radius and mass-central density relations . 32 2.3 Uniformly rotating white dwarfs . 37 2.3.1 The Mass-shedding limit . 38 2.3.2 Secular Instability in rotating and general relativistic con- figurations . 38 2.3.3 Pycnonuclear Reactions . 39 2.3.4 Mass-radius and mass-central density relations . 41 3 Magnetic white dwarfs: Stability and observations 47 3.1 Introduction . 47 3.2 Observations of magnetic white dwarfs . 49 3.2.1 Introduction . 49 3.2.2 Historical background . 51 3.2.3 Mass distribution of magnetic white dwarfs . 53 3.2.4 Spin periods of isolated magnetic white dwarfs . 53 3.2.5 The origin of the magnetic field . 55 3.2.6 Applications . 56 3.2.7 Conclusions . 57 3.3 Stability of Magnetic White Dwarfs . 59 3.3.1 Introduction . 59 3.3.2 Ultra-magnetic white dwarfs . 60 3.3.3 Equation of state and virial theorem violation . -

Stellar Evolution

Stellar Astrophysics: Stellar Evolution 1 Stellar Evolution Update date: December 14, 2010 With the understanding of the basic physical processes in stars, we now proceed to study their evolution. In particular, we will focus on discussing how such processes are related to key characteristics seen in the HRD. 1 Star Formation From the virial theorem, 2E = −Ω, we have Z M 3kT M GMr = dMr (1) µmA 0 r for the hydrostatic equilibrium of a gas sphere with a total mass M. Assuming that the density is constant, the right side of the equation is 3=5(GM 2=R). If the left side is smaller than the right side, the cloud would collapse. For the given chemical composition, ρ and T , this criterion gives the minimum mass (called Jeans mass) of the cloud to undergo a gravitational collapse: 3 1=2 5kT 3=2 M > MJ ≡ : (2) 4πρ GµmA 5 For typical temperatures and densities of large molecular clouds, MJ ∼ 10 M with −1=2 a collapse time scale of tff ≈ (Gρ) . Such mass clouds may be formed in spiral density waves and other density perturbations (e.g., caused by the expansion of a supernova remnant or superbubble). What exactly happens during the collapse depends very much on the temperature evolution of the cloud. Initially, the cooling processes (due to molecular and dust radiation) are very efficient. If the cooling time scale tcool is much shorter than tff , −1=2 the collapse is approximately isothermal. As MJ / ρ decreases, inhomogeneities with mass larger than the actual MJ will collapse by themselves with their local tff , different from the initial tff of the whole cloud. -

PS 224, Fall 2014 HW 4

PS 224, Fall 2014 HW 4 1. True or False? Explain in one or two short sentences. a. Scientists are currently building an infrared telescope designed to observe fusion reactions in the Sun’s core. False. Infrared telescopes cannot see through the Sun. b. Two stars that look very different must be made of different kinds of elements. False. What a star looks like depends on many different properties like mass, age, and size. c. Two stars that have the same apparent brightness in the sky must also have the same luminosity. False. How bright a star appears depends on the luminosity of a stars and its distance away from us. d. Some of the stars on the main sequence of the H-R diagram are not converting hydrogen into helium. False. The main-seuqence is defined as the phase of a star’s life when it burns hydrogen into helium. e. Stars that begin their lives with the most mass live longer than less massive stars because they have so much more hydrogen fuel. False. Massive stars live have shorter lifetimes as they burn through their fuel faster. f. All giants, supergiants, and white dwarfs were once main-sequence stars. True. Main-sequence stars evolve to become giants and supergiants based on their mass and eventually end up as white dwarfs. g. The iron in my blood came from a star that blew up more than 4 billion years ago. True. All elements except hydrogen and helium were produced in stars. h. If the Sun had been born 4½ billion years ago as a high-mass star rather than as a low- mass star, Jupiter would have Earth-like conditions today, while Earth would be hot like Venus. -

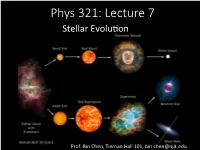

Phys 321: Lecture 7 Stellar Evolu�On

Phys 321: Lecture 7 Stellar Evolu>on Prof. Bin Chen, Tiernan Hall 101, [email protected] Stellar Evoluon • Formaon of protostars (covered in Phys 320; briefly reviewed here) • Pre-main-sequence evolu>on (this lecture) • Evolu>on on the main sequence (this lecture) • Post-main-sequence evolu>on (this lecture) • Stellar death (next lecture) The Interstellar Medium and Star Formation the cloud’s internal kinetic energy, given by The Interstellar Medium and Star Formation the cloud’s internal kinetic energy, given by 3 K NkT, 3 = 2 The Interstellar MediumK andNkT, Star Formation = 2 where N is the total number2 ofTHE particles. FORMATIONwhere ButNNisis the just total OF number PROTOSTARS of particles. But N is just M Mc N c , Our understandingN , of stellar evolution has= µm developedH significantly since the 1960s, reaching = µmH the pointwhere whereµ is the much mean of molecular the life weight. history Now, of by a the star virial is theorem, well determined. the condition for This collapse success has been where µ is the mean molecular weight.due to advances Now,(2K< byU the in) becomes observational virial theorem, techniques, the condition improvements for collapse in our knowledge of the physical | | (2K< U ) becomes processes important in stars, and increases in computational2 power. In the remainder of this | | 3MckT 3 GMc chapter, we will present an overview of< the lives. of stars, leaving de(12)tailed discussions 2 µmH 5 Rc of s3oMmeckTspecia3l pGMhasces of evolution until later, specifically stellar pulsation, supernovae, The radius< may be replaced. by using the initial mass density(12) of the cloud, ρ , assumed here µmH 5 Rc 0 and comtop beac constantt objec throughoutts (stellar theco cloud,rpses).