GT00 Front Matter.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Power Dynamics and Sexual Harassment Reporting in US State Legislative Bodies Halley Norman Macalester College, [email protected]

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Political Science Honors Projects Political Science Department Spring 5-2019 Why We Hear About It, and Why We Don't: Power Dynamics and Sexual Harassment Reporting in US State Legislative Bodies Halley Norman Macalester College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/poli_honors Part of the American Politics Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Political Science Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Norman, Halley, "Why We Hear About It, and Why We Don't: Power Dynamics and Sexual Harassment Reporting in US State Legislative Bodies" (2019). Political Science Honors Projects. 82. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/poli_honors/82 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why We Hear About It, and Why We Don’t: Power Dynamics and Sexual Harassment Reporting in US State Legislative Bodies Halley Norman Advisor: Prof. Julie Dolan Political Science May 1, 2019 Table of Contents Abstract….………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………… 2 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………... 3 Chapter 1………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Cultural Context Chapter -

Chester Alan Arthur by Zachary Karabell Chester Alan Arthur by Zachary Karabell

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Chester Alan Arthur by Zachary Karabell Chester Alan Arthur by Zachary Karabell. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66185231de5f05d8 • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Chester Alan Arthur. by Zachary Karabell, Ph.D. , Arthur M Schlesinger (Editor) Browse related Subjects. When an assassin's bullet killed President Garfield, vice president Chester Arthur was catapulted into the White House. He may be largely forgotten today, but Karabell eloquently shows how this unexpected president rose to the occasion. Read More. When an assassin's bullet killed President Garfield, vice president Chester Arthur was catapulted into the White House. He may be largely forgotten today, but Karabell eloquently shows how this unexpected president rose to the occasion. Read Less. All Copies ( 18 ) Softcover ( 1 ) Hardcover ( 15 ) Choose Edition ( 1 ) Book Details Seller Sort. 2004, Times Books. Las Cruces, NM, USA. Edition: 2004, Times Books Hardcover, Good Details: ISBN: 0805069518 ISBN-13: 9780805069518 Pages: 170 Publisher: Times Books Published: 2004 Language: English Alibris ID: 16692677246 Shipping Options: Standard Shipping: €3,66 Trackable Expedited: €7,33. -

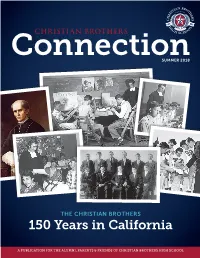

Connection – Summer 2018

ConnectionCHRISTIAN BROTHERS SUMMER 2018 THE CHRISTIAN BROTHERS 150 Years in California A PUBLICATION FOR THE ALUMNI, PARENTS & FRIENDS OF CHRISTIAN BROTHERS HIGH SCHOOL CB Leadership Team Lorcan P. Barnes President Chris Orr Principal June McBride Board of Trustees Director of Finance David Desmond ’94 The Board of Trustees at Christian Brothers High School is comprised of 11 volunteers Assistant Principal dedicated to safeguarding and advancing the school’s Lasallian Catholic college preparatory mission. Before joining the Board of Trustees, candidates undergo Michelle Williams training on Lasallian charism (history, spirituality and philosophy of education) and Assistant Principal Policy Governance, a model used by Lasallian schools throughout the District of Myra Makelim San Francisco New Orleans. In the 2017–18 school year, the board welcomed two new Human Resources Director members, Marianne Evashenk and Heidi Harrison. David Walrath serves in the role of chair and Mr. Stephen Mahaney ’69 is the vice chair. Kristen McCarthy Director of Admissions & The Policy Governance model comprises an inclusive, written set of goals for the school, Communications called Ends Policies, which guide the board in monitoring the performance of the school through the President/CEO. Ends Policies help ensure that Christian Brothers High Nancy Smith-Fagan School adheres to the vision of the Brothers of the Christian Schools and the District Director of Advancement of San Francisco New Orleans. “The Board thanks the families who have entrusted their children to our school,” says Chair David Walrath. “We are constantly amazed by our unbelievable students. They are creative, hardworking and committed to the Lasallian Core Principles. Assisting Connection is a publication of these students are the school’s faculty, staff and administration. -

Social and Cultural Factors of Military Sexual Trauma

Social and Cultural Factors of Military Sexual Trauma Jennifer Fox, LCSW OEF/OIF/OND Mental Health Social Worker Richard L. Roudebush VAMC Indianapolis, Indiana Training Objectives Attendees will be able to: • Define military sexual trauma (MST) • Identify infamous incidents of MST • Explain the military cultural factors that contribute to the high rate of MST • List mental and physical health symptoms/diagnoses often associated with sexual trauma • State supportive responses when sexual trauma is disclosed • Name some of the evidence based psychotherapies to treat mental health diagnoses commonly associated with sexual trauma • List VA programs available to MST survivors • Identify social justice resources for MST survivors Defining Military Sexual Trauma • VA uses the term “military sexual trauma” (MST) to refer to experiences of sexual assault or repeated, threatening sexual harassment experienced while on federal active duty, active duty for training, or inactive duty training. • Any experience in which someone is involved against his/her will. This includes: • Use of physical force • Unable to consent (e.g. intoxicated). Compliance does not mean consent • Pressured into sexual activities (e.g. threats of consequences or promises of rewards) • Unwanted touching, grabbing, unwelcome sexual advances • Oral sex, anal sex, sexual penetration with an object and/or sexual intercourse • Stranger rape • Acquaintance rape Infamous incidents of MST • 1991 Tailhook Scandal, Las Vegas, Nevada • 1996 Aberdeen Proving Ground, Aberdeen, Maryland 1991 Tailhook Scandal • Annual Tailhook convention, with approximately 4,000 attendees, including active, reserve and retired personnel. • The 1991 intended focus was to debrief Navy and Marine Corps aviation regarding Operation Desert Storm. • More than 100 Navy and Marine aviation officers were alleged to have sexually assaulted at least 83 women and 7 men. -

1908 Journal

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 12, 1908. The court met pursuant to law. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham, Mr. Justice McKenna, Mr. Justice Holmes, Mr. Justice Day and Mr. Justice Moody. James A. Fowler of Knoxville, Tenn., Ethel M. Colford of Wash- ington, D. C., Florence A. Colford of Washington, D. C, Charles R. Hemenway of Honolulu, Hawaii, William S. Montgomery of Xew York City, Amos Van Etten of Kingston, N. Y., Robert H. Thompson of Jackson, Miss., William J. Danford of Los Angeles, Cal., Webster Ballinger of Washington, D. C., Oscar A. Trippet of Los Angeles, Cal., John A. Van Arsdale of Buffalo, N. Y., James J. Barbour of Chicago, 111., John Maxey Zane of Chicago, 111., Theodore F. Horstman of Cincinnati, Ohio, Thomas B. Jones of New York City, John W. Brady of Austin, Tex., W. A. Kincaid of Manila, P. I., George H. Whipple of San Francisco, Cal., Charles W. Stapleton of Mew York City, Horace N. Hawkins of Denver, Colo., and William L. Houston of Washington, D. C, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would then commence the call of the docket, pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 13, will be as follows: Nos. 92, 209 (and 210), 198, 206, 248 (and 249 and 250), 270 (and 271, 272, 273, 274 and 275), 182, 238 (and 239 and 240), 286 (and 287, 288, 289, 290, 291 and 292) and 167. -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

Claremen & Women in the Great War 1914-1918

Claremen & Women in The Great War 1914-1918 The following gives some of the Armies, Regiments and Corps that Claremen fought with in WW1, the battles and events they died in, those who became POW’s, those who had shell shock, some brothers who died, those shot at dawn, Clare politicians in WW1, Claremen courtmartialled, and the awards and medals won by Claremen and women. The people named below are those who partook in WW1 from Clare. They include those who died and those who survived. The names were mainly taken from the following records, books, websites and people: Peadar McNamara (PMcN), Keir McNamara, Tom Burnell’s Book ‘The Clare War Dead’ (TB), The In Flanders website, ‘The Men from North Clare’ Guss O’Halloran, findagrave website, ancestry.com, fold3.com, North Clare Soldiers in WW1 Website NCS, Joe O’Muircheartaigh, Brian Honan, Kilrush Men engaged in WW1 Website (KM), Dolores Murrihy, Eric Shaw, Claremen/Women who served in the Australian Imperial Forces during World War 1(AI), Claremen who served in the Canadian Forces in World War 1 (CI), British Army WWI Pension Records for Claremen in service. (Clare Library), Sharon Carberry, ‘Clare and the Great War’ by Joe Power, The Story of the RMF 1914-1918 by Martin Staunton, Booklet on Kilnasoolagh Church Newmarket on Fergus, Eddie Lough, Commonwealth War Grave Commission Burials in County Clare Graveyards (Clare Library), Mapping our Anzacs Website (MA), Kilkee Civic Trust KCT, Paddy Waldron, Daniel McCarthy’s Book ‘Ireland’s Banner County’ (DMC), The Clare Journal (CJ), The Saturday Record (SR), The Clare Champion, The Clare People, Charles E Glynn’s List of Kilrush Men in the Great War (C E Glynn), The nd 2 Munsters in France HS Jervis, The ‘History of the Royal Munster Fusiliers 1861 to 1922’ by Captain S. -

Keynote Speaker, Dr. Zachary Karabell Is Head of Global Strategy at Envestnet, a Publicly Traded Financial Services Firm

Keynote Speaker, Dr. Zachary Karabell is Head of Global Strategy at Envestnet, a publicly traded financial services firm. He is also President of River Twice Capital Advisors, a money management firm. Previously, he was Executive Vice President, Chief Economist, and Head of Marketing at Fred Alger Management, a New York-based investment firm. He was also President of Fred Alger & Company, a broker-dealer; Portfolio Manager of the China-U.S. Growth Fund (CHUSX); and Executive Vice President of Alger’s Spectra Funds. At Alger, he oversaw the creation, launch and marketing of several funds, led corporate strategy for strategic acquisitions, and represented the firm at public forums and in the media. Educated at Columbia, Oxford and Harvard, where he received his Ph.D., Karabell has taught at several leading universities, including Harvard and Dartmouth, and has written widely on economics, investing, history and international relations. His most recent book, The Leading Indicators: A Short History of the Numbers That Rule Our World, was published by Simon & Schuster in February 2014. He is the author of eleven previous books. He sits on the board of the New America Foundation and the Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs, and is a Senior Advisor for BSR, a membership organization that works with global corporations on issues of sustainability. As a commentator, Karabell writes “The Edgy Optimist” column for Slate. He is a CNBC Contributor, a regular commentator on MSNBC, and Contributing Editor for The Daily Beast, and writes for such publications as The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Time Magazine, The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Financial Times, and Foreign Affairs. -

The Secret Sauce for Organizational Success Communications and Leadership on the Same Page

The Secret Sauce for Organizational Success Communications and Leadership on the Same Page By Tom Jurkowsky Rear Admiral, US Navy, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Director, Air University Press Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Maj Richard Harrison Names: Jurkowsky, Tom, 1947- author. | Air University Project Editor (U.S.). Press, issuing body. Dr. Stephanie Havron Rollins Title: The secret sauce for organizational success : com- Maranda Gilmore munications and leadership on the same page / Tom Jurkowsky. Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations Daniel Armstrong Description: Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama : Air University Press, [2019] Composition and Prepress Production Includes bibliographical references and index. | Sum- Nedra Looney mary: “This book provides examples of constants that communicators and their leaders should stay focused on. Those constants are: (1) responsiveness to the media; (2) providing access to the media; (3) ensuring good working relationships with the media; and (4) always Air University Press maintaining one’s integrity. Each chapter is dedicated to 600 Chennault Circle, Building 1405 one or several examples of these concepts”—Provided Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6010 by publisher. Identifiers: LCCN 2019040172 (print) | LCCN https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/ 2019040173 (ebook) | ISBN 9781585663019 (paper- AUPress/ back) | ISBN 9781585663019 (Adobe PDF) Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AirUnivPress Subjects: LCSH: United States. Navy--Public relations. | and Communication--United -

SPRING 2016 BANNER RECIPIENTS (Listed in Alphabetical Order by Last Name)

SPRING 2016 BANNER RECIPIENTS (Listed in Alphabetical Order by Last Name) Click on name to view biography. Render Crayton Page 2 John Downey Page 3 John Galvin Page 4 Jonathan S. Gibson Page 5 Irving T. Gumb Page 6 Thomas B. Hayward Page 7 R. G. Head Page 8 Landon Jones Page 9 Charles Keating, IV Page 10 Fred J. Lukomski Page 11 John McCants Page 12 Paul F. McCarthy Page 13 Andy Mills Page 14 J. Moorhouse Page 15 Harold “Nate” Murphy Page 16 Pete Oswald Page 17 John “Jimmy” Thach Page 18 Render Crayton_ ______________ Render Crayton Written by Kevin Vienna In early 1966, while flying a combat mission over North Vietnam, Captain Render Crayton’s A4E Skyhawk was struck by anti-aircraft fire. The plane suffered crippling damage, with a resulting fire and explosion. Unable to maintain flight, Captain Crayton ejected over enemy territory. What happened next, though, demonstrates his character and heroism. While enemy troops quickly closed on his position, a search and rescue helicopter with armed escort arrived to attempt a pick up. Despite repeated efforts to clear the area of hostile fire, they were unsuccessful, and fuel ran low. Aware of this, and despite the grave personal danger, Captain Crayton selflessly directed them to depart, leading to his inevitable capture by the enemy. So began seven years of captivity as a prisoner of war. During this period, Captain Crayton provided superb leadership and guidance to fellow prisoners at several POW locations. Under the most adverse conditions, he resisted his captor’s efforts to break him, and he helped others maintain their resistance. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-. Tuesday, April 30, 1991

April 30, 1991 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 9595 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-.Tuesday, April 30, 1991 The House met at 12 noon. around; the person to your left, the minute and to revise and extend his re The Chaplain, Rev. James David person to your right, they may very marks.) Ford, D.D., offered the following pray significantly be out of work in the very Mr. FROST. Mr. Speaker, during the er: near future. And remember, the person last Presidential campaign, there was a Gracious God, may we not express next to you is looking at you. refrain of "Where's George?" asking the attitudes of our hearts and minds And what is the answer of this ad where then-Vice President Bush was on only in words or speech, but in deeds ministration to this problem? Nothing. a variety of issues. and in truth. May our feelings of faith Where is the legislation to take care of Unfortunately for the country, that and hope and love find fulfillment in all those unemployed who have lost refrain rings very true today. charity and caring and in the deeds of their jobs where there is no unemploy Our President, George Bush, loved justice. Teach us always, 0 God, not ment compensation? There is not any. foreign policy and handled the Persian only to sing and say the words of What is the answer of this adminis Gulf situation well, but our President praise, but to be vigorous in our deeds tration to the problem of the recession is nowhere. to be found when it comes of mercy and kindness. -

Sexual Violence As an Occupational Hazard and Condition of Confinement in the Closed Institutional Systems of the Military and Detention

California Western School of Law CWSL Scholarly Commons Faculty Scholarship 2017 Sexual Violence as an Occupational Hazard and Condition of Confinement in the Closed Institutional Systems of the Military and Detention Hannah Brenner California Western School of Law, [email protected] Kathleen Darcy University of Chicago Sheryl Kubiak Michigan State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/fs Part of the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation 44 Pepp. L. Rev. 881 (2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CWSL Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CWSL Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sexual Violence as an Occupational Hazard & Condition of Confinement in the Closed Institutional Systems of the Military and Detention Hannah Brenner,* Kathleen Darcy,** & Sheryl Kubiak*** Abstract Women in the military are more likely to be raped by other service members than to be killed in combat. Female prisoners internalize rape by corrections officers as an inherent part of their sentence. Immigrants held in detention fearing deportation or other legal action endure rape to avoid compromising their cases. This Article draws parallels among closed institutional systems of prisons, immigration detention, and the military. The closed nature of these systems creates an environment where sexual victimization occurs in isolation, often without knowledge of or intervention by those on the outside, and the internal processes for addressing this victimization allow for sweeping discretion on the part of system actors. This Article recommends a two-part strategy to better make victims whole and effect systemic, legal, and cultural change: the use of civil lawsuits generally, with a focus on the class action suit, supplemented by administrative law to enforce federal rules on sexual violence in closed systems.