2008 PTLC Research Proposals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of COLORADO BOULDER 505939 UC Lawcover3 6/12/12 11:42 AM Page 2

505939 UC LawCover2 6/11/12 3:08 PM Page 1 UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER 505939 UC LawCover3 6/12/12 11:42 AM Page 2 Table of Contents Welcome 1 Boulder 2 Colorado Law 4 Academics 6 Experiential Learning 9 Research Centers 11 Student Life 12 Career Development 14 Faculty 17 Admissions and Financial Aid 19 Student Body IBC UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BOULDER Office of Admissions 403 UCB Boulder, CO 80309-0403 [email protected] 303-492-7203 This viewbook is a statement of current practices, but it does not establish a contract. The University of Colorado Law School and the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado retain the right to modify the information about the Law School at any time. The University of Colorado does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, creed, religion, sexual orientation, or veteran status in admission and access to, and treatment and employment in, its educational programs and activities. Editing by Kristine Jackson and Keri Ungemah, Colorado Law School, and Michelle Asakawa, CU-Boulder University Communications Project Management by Kim Warner, CU-Boulder Marketing and Creative Services Design and Production by Barb Diehl and Michael Campbell, CU-Boulder Mar- keting and Creative Services Photography by Casey A. Cass, Glenn Asakawa, and Patrick Campbell, University Communications, except for photo of Ryan Haygood, page 16, courtesy of Colorado College Printed on recycled paper, June 2012. www.colorado.edu/law 505939 UC LawText2 6/11/12 3:09 PM Page 1 WELCOME Selecting a law school is a momentous and individual decision. -

Denver Margaret Hunt, Amherst College University of Chicago Press Adam Matthew Publications Institute of Historical Research Huntington Library Denver Art Museum

ABOUT NACBS The North American Conference on British Studies (NACBS) is a scholarly society founded in 1950 and dedicated to all aspects of British Studies. The NACBS sponsors publications and an annual conference, as well as several academic prizes and graduate fellowships. Its regional affiliates include the Mid-Atlantic Conference on British Studies (MACBS), the Midwest Conference on British Studies (MWCBS), the Northeast Conference on British Studies (NECBS), the Pacific Coast Conference on British Studies (PCCBS), the Southern Conference on British Studies (SCBS), and the Western Conference on British Studies (WCBS). For more information about the NACBS and its affiliates, secure on-line registration for the 2005 meeting, and reservations for the conference hotel, go to www.NACBS.org. The 2006 conference, held in conjunction with the Northeast Conference on British Studies (NECBS) will be held November 16-19 in Boston, Massachusetts. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The NACBS and WCBS thank the following institutions and individuals for their contributions: Anna Misticoni and Meagan Schenkelberg and the Department of History, Villanova University Myra Rich and the Department of History, University of Colorado at Denver Margaret Hunt, Amherst College University of Chicago Press Adam Matthew Publications Institute of Historical Research Huntington Library Denver Art Museum NACBS Executive Committee President Cynthia Herrup, University of Southern California Vice President William Lubenow, Richard Stockton College of New Jersey Immediate Past President -

Zonta International Jane M. Klausman Women in Business Scholarship 2020 District, Region and International Recipients District and International Recipients

Zonta International Jane M. Klausman Women in Business Scholarship 2020 District, Region and International Recipients District and International Recipients District/ Country of Nominating Zonta Name of Recipient School/Country Field of Study Region Citizenship Club/Country 1 Shanley Weston Canada Halifax, Canada Saint Mary’s University, Canada Business Management The Wharton School of the University of 3 Caroline Simon USA Brooklyn, USA Master of Business Administration Pennsylvania, USA 6 Tara Liegel USA Janesville, USA University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, USA Accounting/Finance 22 Sanuri De Silva Wimalatunga Sri Lanka Beaudesert Area Inc, Australia Griffith University, Australia Finance Kathmandu University School of 25 Rupsi Parajuli Nepal Kathmandu, Nepal Finance Management (KUSOM), Nepal St Antony's College, University of Oxford, Master of Philosophy in 28 Laura Ballerini Italy Milano-Sant Ambrogio, Italy United Kingdom Development Economics District/Region Recipients District/ Country of Nominating Zonta Name of Recipient School/Country Field of Study Region Citizenship Club/Country Business and Management, Design, Innovation and 2 Angela Fu USA Albany, USA Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, USA Society 4 Madison Buchholz USA Niagara Falls, USA Niagara University, USA Strategic Marketing 5 Lauren Black USA Columbus, USA University of Pennsylvania, USA Real Estate and Finance 7 Santina Zito USA Jamestown, USA University of Jamestown, USA Accounting, Business and Finance 8 Ching Ying (Jessica) Hu Canada Victoria, Canada University of -

KELLIE MARIN Communication Arts & Sciences | the Pennsylvania State University 234 Sparks Building | University Park, PA 16802 [email protected] | (814) 441-3741

CURRICULUM VITAE KELLIE MARIN Communication Arts & Sciences | The Pennsylvania State University 234 Sparks Building | University Park, PA 16802 [email protected] | (814) 441-3741 EDUCATION Ph.D., The Pennsylvania State University, anticipated 2020. Communication and Rhetoric Dissertation: “The rhetoric of anonymity: Secrecy, exposure, and the circulation of affect within the neoliberal security state” Advisor: Jeremy D. Engels, Ph.D. Certificate of Leader Development, National Security Seminar of the U.S. Army War College, 2018. National Security and Strategy M.A., University of Colorado Denver, December 2015. Communication and Rhetoric Special writing project: “Following @CIA: Preserving institutional secrecy through the rhetoric of pseudo transparency” Advisor: Brian L. Ott, Ph.D. B.A., University of Washington Tacoma, 2011. Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences – Communication Dean’s List, Winter & Spring, 2011. A.A., Green River Community College, 2007. General Studies Study Abroad Program, University of Melbourne, Australia & Unitech, New Zealand, 2007. AWARDS & RECOGNITION Predoctoral Fellow, Center for Humanities and Information, Penn State University, 2019-2020. Nominated Invitation, 64th Annual U.S. Army War College National Security Seminar, June 2018. Speaker, Commencement Ceremony, Department of Communication, University of Colorado Denver, December 2015. Wrage-Baskerville Award, Public Address Division, National Communication Association, November 2014. Co-recipient with Brian L. Ott and Hamilton Bean. RESEARCH INTERESTS National security rhetoric and how it intersects with issues and theories concerned with terrorism, affect, aesthetics and materiality, media studies, social media, and the production of the citizen subject. PUBLICATIONS Peer- Marin, K. (2020). Pseudo-sousveillance: (Re)imagining immigration Reviewed narratives and surveillance practices by experiencing “Use of Force.” Special issue “Ubiquitously Surveilled Bodies” in Screen Bodies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Experience, Perception, and Display. -

2017 Women in Aerospace Symposium Schedule

2017 Women in Aerospace Symposium Schedule CU Boulder Tuesday May 30th, 2017 6:00 - 8:00 pm Welcome Dinner Welcome Remarks: Penny Axelrad, Professor and Chair, Smead Aerospace Café Mexicali Engineering Sciences Wednesday May 31st, 2017 7:45 am Meet outside hotel to walk to campus Best Western 8:00 - 8:30 am Walk from hotel to campus 8:30 - 9:00 am Opening Remarks: Bobby Braun, Dean CU College of Engineering and Applied Science, Smead Chair of Space Technology Aeronautics Session 1: 9:00 - 9:15 am Nicoletta Fala, Purdue University Communicating Data Driven Post Flight Feedback to General Aviation Pilots 9:15 - 9:30 am Jessica Morgan, Pennsylvania State University Further Development of Nozzle Fluidic Insert Noise Reduction Method for Supersonic Jet Engines 9:30 - 9:45 am Yibin Zhang, Princeton University Laser Diagnostics for Super- and Hypersonic Flight 9:45 - 10:00 am Mahdis Bisheban, The George Washington University Computational Geometric Identification for the Quadrotor Dynamics in Wind ITLL Active Learning Center (1B50) Fields 10:00 - 10:30 am Coffee Break Astronautics Session 1: 10:30 - 10:45 am Jayati Athavale, Georgia Institute of Technology Transient Thermal Response and Control of Data Centers 10:45 - 11:00 am Sara Hrbek, University of Colorado, Boulder On Characterizing Performance of GPS Signal Cancellation in Presence of Bandlimiting and Quantization 11:00 - 11:15 am Elaine Petro, University of Maryland, College Park Development of a Water-Propelled Electrodeless Plasma Thruster 11:15 - 11:30 am Ana Diaz Artiles, Cornell -

University Placements the Following Gives an Overview of the Many Universities Tanglin Graduates Have Attended Or Received Offers from in 2018 and 2019

University Placements The following gives an overview of the many universities Tanglin graduates have attended or received offers from in 2018 and 2019. United Kingdom United States of America Abertay University Amherst College Aston University Arizona State University Student Destinations 2019 Bath Spa University Berklee College of Music Bournemouth University Boston University Central School of St Martin’s, UAL Brown University City, University of London Carleton College 1% Malaysia Coventry University Chapman University 7% De Montfort University Claremont McKenna College National Durham University Colorado State University 1% Italy Service Edinburgh Napier University Columbia College, Chicago Falmouth University Cornell University 1% Singapore Goldsmiths, University of London Duke University 1% Hong Heriot-Watt University Elon University Kong 1% Spain Imperial College London Emerson College King’s College London Fordham University 2% Holland Lancaster University Georgia Institute of Technology Liverpool John Moores University Georgia State University 4% Gap Year 64% UK London School of Economics and Hamilton College Political Science Hult International Business School, 2% Canada London South Bank University San Francisco 6% Australia Loughborough University Indiana University at Bloomington Northumbria University John Hopkins University Norwich University of the Arts Loyola Marymount University 11% USA Nottingham Trent University Michigan State University Oxford Brookes University New York University Queen’s University Belfast Northeastern -

Samuel B. Siewert

Samuel B. Siewert [email protected] Embry Riddle Aeronautical University, Office 145, King Building, 3700 Willow Creek Rd, Prescott, AZ 86301 Cell: (303) 641-3999, Office: (928) 777-6929 SUMMARY Over 20 years industry experience and five years tenure track teaching, research and service in software and computer engineering. Helped to raise $30M start-up capital as a CTO, managed IP and lead R&D teams. Co-founder of new graduate programs and contributor to start-up of a research center of excellence. PRESENT POSITIONS AND APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor, Computer, Electrical, and Software Engineering, Embry Riddle Aeronautical Univ. Assistant Professor Adj., Electrical, Computer, and Energy Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder Founder, Senior Consultant, Transductive LLC EDUCATION 2000 Ph.D. Computer Science University of Colorado, Boulder Dissertation: Real-time Execution Performance Agent, advised by Dr. Gary Nutt 1993 M.S. Computer Science University of Colorado, Boulder Thesis: A Common Core Language Design for Layered Extension, advised by Dr. Ben Zorn Project: Artificial Neural Network and DSP kernel cancerous cell detection, Optical Computing Ctr. 1991 28 Credit Hours, Computer System Design Engineering University of Houston, Clear Lake 1989 B.S. Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering University of Notre Dame 1985 7.5 Credit Hours, Early Admission, Physics/Philosophy University of California, Berkeley ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2014-present Embry Riddle Aeronautical University Asst. Professor, Software Engineering Teaching: Software and Computer Engineering Research: Software Defined Multi-Spectral Imaging System (SDMSI), UAS, IoT, sensor networks 2012-2014 University of Alaska Anchorage Asst. Professor, Computer Engineering Teaching: Computer Science and Engineering Research: Embedded Computer and Machine Vision, UAS/UAV Video Analytics 2000-present University of Colorado Boulder Adjunct Faculty, Computer Engineering 2012-present Asst. -

Class of 2020 College Acceptances

CLASS OF 2020 COLLEGE ACCEPTANCES Fashion Institute of Technology American University Fordham University Art Center College of Design Franklin and Marshall College Belmont University George Washington University Binghamton University Georgetown University Birkbeck, University of London Georgia Institute of Technology Boston College Georgia Institute of Technology Boston University Helsinki School of Business Brandeis University Indiana University-Bloomington Bridgewater State University Iowa State University Brown University Keio University Carnegie Mellon University Kenyon College Case Western Reserve University Laguna College of Art and Design Clark University Lehigh University Columbia University Loyola Marymount University Cooper Union For the Advancement of Science and Art McGill University Cornell University Merrimack College Dartmouth College Michigan State University Depaul University NewYork University Drew University Northeastern University Drexel University Northwestern University Duke University Nyu Shanghai Emerson College Okanagan College Emory University Otis College of Art and Design Pennsylvania State University-Main Campus Ulster University Pepperdine University United States Naval Academy Pomona College University of Michigan - Ann Arbor Pratt Institute-Main University At Buffalo Purdue University-Main Campus University of Alberta Queen's University University of California - Irvine Rhode Island School of Design University of California - Santa Barbara Rice University University of California at Berkeley Rose-Hulman -

Graduate Placement in Phd Programs

Graduate Placement in PhD Programs The following students graduated with a master’s degree with an emphasis in Chinese from the University of Colorado Boulder and have gone on to pursue a doctorate degree here or at other first-rank institutions. 1 1991 YANG Xiaobin 楊小濱 Yale University 2 1992 GUO Aihua Indiana University 3 LIU Jianmei 劉劍梅 Columbia University 4 SONG Yongyi 宋永毅 Pennsylvania State University 5 1993 WANG Gang (Richard G. Wang) University oF Chicago 6 Matthew CARTER University oF Washington 7 1994 Steven DAY University oF California Los Angeles 8 Robin VISSER Columbia University 9 Haili KONG 孔海立 CU Boulder 10 1995 Scott GALER University oF WisConsin 11 1997 ZHANG Dongming Cornell University 12 1998 Brigitta LEE PrinCeton University 13 Stephan KORY Indiana University 14 Michelle LOW 劉潔貞 CU Boulder 15 YU Shiyi CU Boulder 16 1999 Timothy DAVIS Columbia University 17 Tina JENKINS (HARDING) CU Boulder 18 Timothy CHAN CU Boulder 19 2000 WANG Ping University oF Washington 20 D. Andrew KNIGHT Yale University 21 JIA Jinhua 賈晉華 CU Boulder 22 2001 Mary TRECHOCK Cornell University 23 Solomon WEIL University oF Washington 24 2002 HONG Yue Harvard University 25 Adam SCHWARTZ University oF Chicago 26 2003 ZHANG Huicong 张慧聪 Harvard University 27 Shelley Wing CHAN CU Boulder 28 Jonathan PETTIT Indiana University 29 WANG Yanning University oF Washington 30 2004 Nicole BARNES University oF California Irvine 31 FAN Lili CU Boulder 32 2005 WU Jie University oF Washington 33 David BOYD Indiana University 34 Bryna TUFT University oF Oregon 35 2006 -

FY 2018-19 Economic Impact

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO Economic Contribution of the University of Colorado on the State and Counties of Operations Prepared for: Vice President for Budget and Finance and Chief Financial Officer Conducted by: BUSINESS RESEARCH DIVISION Leeds School of Business University of Colorado Boulder 420 UCB Boulder, CO 80309-0420 colorado.edu/business/brd February 2020 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Literature Review .......................................................................................................................................... 5 The University of Colorado ........................................................................................................................... 6 Students ................................................................................................................................................... -

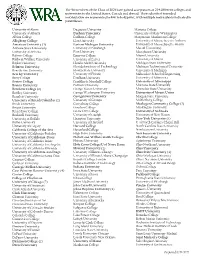

233 Different Colleges and Universities

The 96 members of the Class of 2021 have gained acceptances at 234 different colleges and universities in the United States, Canada and abroad. Their schools of intended matriculation are represented below in bold print, with multiple matriculants indicated in parentheses. University of Akron Duquesne University Marietta College University of Alberta Durham University University of Mary Washington Albion College Earlham College Marymount Manhattan College Allegheny College Elon University University of Massachusetts-Amherst American University (3) Eastern Michigan University University of Massachusetts-Boston Arizona State University University of Edinburgh McGill University) University of Arizona Elon University Mercyhurst University Babson College Emerson College Miami University Baldwin Wallace University University of Exeter University of Miami Baylor University Florida A&M University Michigan State University Belmont University Florida Institute of Technology Michigan Technological University Benedictine University Florida State University University of Michigan Bentley University University of Florida Milwaukee School of Engineering Berry College Fordham University University of Minnesota Boston College Franklin & Marshall College University of Mississippi Boston University Furman University Montana State University Bowdoin College (2) George Mason University Montclair State University Bradley University George Washington University University of Mount Union Brandeis University Georgetown University Morgan State University University -

MBA RANKINGS 2016 MBA RANKINGS North America

MBA RANKINGS 2016 MBA RANKINGS north america Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute: Lally Tier One Rochester Institute of Technology: Saunders Seattle University: Albers American University: Kogod Saint Joseph’s University: Haub Auburn University Saint Mary’s College: School of Economics & Business Administration Boston University: Questrom Temple University: Fox Bryant University Texas A&M University- College Station: Mays California State University- Chico Texas Christian University: Neeley California State University- Long Beach University of Alberta California State University-San Bernardino University of California at Berkeley: Haas California State University-East Bay University of California at Davis Case Western Reserve University: Weatherhead University of California-San Diego: Rady Chapman University: Argyros University of Cincinnati: Lindner College of William and Mary: Mason** University of Colorado- Colorado Springs Colorado Technical University University of Connecticut Drexel University: LeBow** University of Delaware: Lerner** Florida International University University of Hawaii- Manoa: Shidler Fordham University University of Louisiana- Lafayette: Moody Georgetown University: McDonough University of Massachusetts- Boston Georgia State University: Robinson University of Massachusetts- Lowell Gonzaga University University of Michigan-Flint HEC Montreal University of North Carolina-Charlotte: Belk** Jacksonville University University of Oklahoma: Price Kennesaw State University: Coles University of Oregon: Lundquist Kent State