Margaret Conrad George Nowlan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standing Committee on Economic

Standing Committee on Resources ANNUAL REPORT 2014 © 2014 Her Majesty the Queen in right of the Province of Nova Scotia Halifax ISSN: 0837-2551 This document is also available on the Internet at the following address: http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/committees/reports/resources Standing Committee on Resources Annual Report 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ii Membership ii Membership Changes ii Procedures and Operations iii Notices, Transcripts and Reports iii Research Material iv Acknowledgements iv Witnesses v PUBLIC HEARINGS Organizational/Agenda Setting Meeting 1 Report of the Maritime Lobster Panel 3 Forest Products Association of Nova Scotia 5 Nova Scotia Mink Breeders Association 7 Christmas Tree Council of Nova Scotia/Agenda Setting 9 STATEMENT OF SUBMISSION 13 APPENDICES Appendix A - Motions 17 Appendix B - Documentation 19 i Standing Committee on Resources Annual Report 2014 INTRODUCTION The Standing Committee on Resources, an all-party Committee of the House of Assembly, was struck at the beginning of the First Session of the Sixty-Second General Assembly. Pursuant to Rule 60(2)(e) of the Province of Nova Scotia Rules and Forms of Procedure of the House of Assembly: (e) The Resources Committee is established for the purpose of considering matters normally assigned to or within the purview of the Departments and Ministers of Agriculture and Marketing, of the Environment, of Fisheries and of Natural Resources. 1987 R. 60(2); am. 1993; am. 1996. MEMBERSHIP There shall be no more than nine Members of the Legislative Assembly appointed to this Committee. The current membership of the Resources Committee is as follows: Mr. Gordon Wilson, MLA (Chair) Mr. -

Regular Session of Municipal Council Held on December 20, 2011, at the Municipal Administration Building, Annapolis Royal, N.S

MUNICIPAL COUNCIL December 20, 2011 SUMMARY OF MOTIONS MOTION 111220.01 Minutes – Regular Session, November 15, 2011 ...................................................1 MOTION 111220.02 Annapolis County MPS LUB (Wind Power) – Add Effective Date ....................1 MOTION 111220.03 S2 Building Bylaw – Final Reading ........................................................................2 MOTION 111220.04 C7 Elections Deposit Bylaw – Final Reading .........................................................2 MOTION 111220.05 In-Camera, Section 22 (2) (e) ..................................................................................2 MOTION 111220.06 February Council - Inglewood ...............................................................................2 MOTION 111220.07 Bridgetown Volunteer Fire Department – Loan Payments .................................2 MOTION 111220.08 Bridgetown Volunteer Fire Department – Release of Funds ..............................3 MOTION 111220.09 AM-1.3.1 Presentation of Annual Reports Policy - Amend ...................................3 MOTION 111220.10 M9 Tax Deed Bylaw - Amend ..................................................................................3 MOTION 111220.11 AM-2.1.4 Vacation Leave Policy - Amend ..............................................................3 MOTION 111220.12 AM-2.1.5 Sick Leave Policy - Amend ......................................................................3 MOTION 111220.13 AM-1.4.9 Community Grants Policy - Amend ........................................................3 -

October 8, 2013 Nova Scotia Provincial General

47.1° N 59.2° W Cape Dauphin Point Aconi Sackville-Beaver Bank Middle Sackville Windsor μ Alder Junction Point Sackville-Cobequid Waverley Bay St. Lawrence Lower Meat Cove Capstick Sackville Florence Bras d'Or Waverley- North Preston New Waterford Hammonds Plains- Fall River- Lake Echo Aspy Bay Sydney Mines Dingwall Lucasville Beaver Bank Lingan Cape North Dartmouth White Point South Harbour Bedford East Cape Breton Centre Red River Big Intervale Hammonds Plains Cape North Preston-Dartmouth Pleasant Bay Bedford North Neils Harbour Sydney Preston Gardiner Mines Glace Bay Dartmouth North South Bar Glace Bay Burnside Donkin Ingonish Minesville Reserve Mines Ingonish Beach Petit Étang Ingonish Chéticamp Ferry Upper Marconi Lawrencetown La Pointe Northside- Towers Belle-Marche Clayton Cole Point Cross Victoria-The Lakes Westmount Whitney Pier Park Dartmouth Harbour- Halifax Sydney- Grand Lake Road Grand Étang Wreck Cove St. Joseph Leitches Creek du Moine West Portland Valley Eastern Shore Whitney Timberlea Needham Westmount French River Fairview- Port Morien Cap Le Moine Dartmouth Pier Cole Balls Creek Birch Grove Clayton Harbour Breton Cove South Sydney Belle Côte Kingross Park Halifax ^ Halifax Margaree Harbour North Shore Portree Chebucto Margaree Chimney Corner Beechville Halifax Citadel- Indian Brook Margaree Valley Tarbotvale Margaree Centre See CBRM Inset Halifax Armdale Cole Harbour-Eastern Passage St. Rose River Bennet Cape Dauphin Sable Island Point Aconi Cow Bay Sydney River Mira Road Sydney River-Mira-Louisbourg Margaree Forks Egypt Road North River BridgeJersey Cove Homeville Alder Point North East Margaree Dunvegan Englishtown Big Bras d'Or Florence Quarry St. Anns Eastern Passage South West Margaree Broad Cove Sydney New Waterford Bras d'Or Chapel MacLeods Point Mines Lingan Timberlea-Prospect Gold Brook St. -

36 - Electoral District of Kings South Nova Scotia Electoral Boundaries Commission Final Report (2018-19)

Nova Scotia Electoral Districts 36 - Electoral District of Kings South Nova Scotia Electoral Boundaries Commission Final Report (2018-19) 3 5 - K 3 in 7 g - K s in No gs rt W h e st H ig hw a y 10 L 1 or ett a A ve A ar on Dr d R p o h s i B H ig h hw t u L ay a 1 o u r B P S i e e nt W o R rlan L rd d a e d n e r d b D e r n D S M L m S t o u t d t ve l t tt C a s n R r M e e h V d a t Pi i rie G h W u ne ew D t o c R r u h s re d t S Birc s o h r g t n s C r D M S o r C r e i t rc g y on s N K b Pl n s g s - i ro or d L C nw n K a C a i g 7 R ng lli n Pro - l i C s K i spect Rd 3 lle re 6 a s - K t D 3 it M r - p a 6 p r S l 3 e C 5 r 3 t D Coldbrook r n r D a D h e h g r e a l e r D h M a a s e S r A d n Prospect A d R B es n t R t Harringto d M n Rd rt a Lo h ck k ha c rt o Rd L r Tu D p t per n L i a d L o k e R a P k e s i d e Nort r E h D D n r g R e l iver Rd k Tupper Lake a i L s h Pros Inchley LnDon Sheila Ln M pect t Rd n R d d H H R i igh g wa 2 d y 1 h l w e i f a o y h c 1 Mo C S 0 r ris C r 1 e Casey Corner a s n a a r C D n North Alton ry o ar m H m C r h D t e McGee Lake r e o ab r s iz 3 l A c s n ve 5 E a i na a J R o - a H l o ne K d w 3 C S e s i n A R 6 t ve g Highbury d s d - d R r N R D C K nn w r o o o e r i r C D rn e n s s t a e u g h n v T i D M H s M A i r A S i g s l c rd o l h l v w i e e ut R l e a a h p A n N d m d A m Jordan St Ne ir ve w y a A A C Ol P v is a l e l na l T a a n r o Rd w p D n s r l Av d e r e i r M r o n la il l ne e C e a i C r A r s M r B r ve a r D D D e n l i v P d n n M o r r t -

Standing Committee on Economic

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 © 2015 Her Majesty the Queen in right of the Province of Nova Scotia Halifax ISSN: 0837-2551 This document is also available on the Internet at the following address: http://nslegislature.ca/index.php/committees/reports/resources Legislative PO Box 2630, Station M Halifax, Nova Scotia Committees Office B3J 3P7 House of Assembly Telephone: (902) 424-4432 Nova Scotia Fax: (902) 424-0513 Hon. Kevin Murphy Speaker House of Assembly Province House Halifax, Nova Scotia Dear Mr. Speaker: On behalf of the Standing Committee on Resources, I am pleased to submit the Annual Report of the Committee for the period from September 2014 to August 2015 of the Sixty-Second General Assembly. Respectfully submitted, Mr. Gordon Wilson, MLA, Clare-Digby Chair Standing Committee on Resources Halifax, Nova Scotia 2015 Standing Committee on Resources Annual Report 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ii Membership ii Membership Changes ii Procedures and Operations iii Notices, Transcripts and Reports iii Research Material iv Acknowledgements iv PUBLIC HEARINGS November 20, 2014 1 Department of Agriculture Re: Strawberry Industry December 18, 2104 3 Nova Scotia Beekeepers Association & Agenda Setting Re: Industry Overview January 15, 2015 5 Farmers’ Markets of Nova Scotia Re: Overview March 24, 2015 6 Department of Energy Re: Geoscience Research for Nova Scotia’s Offshore Growth May 21, 2015 7 The Winery Association of Nova Scotia Re: Nova Scotia Wine Industry June 18, 2105 8 Nova Scotia Silviculture Contractors’ Association & Agenda Setting Re: Overview STATEMENT OF SUBMISSION 11 APPENDICES Appendix A - Motions 13 Appendix B - Documentation 16 i Standing Committee on Resources Annual Report 2015 INTRODUCTION The Standing Committee on Resources, an all-party Committee of the House of Assembly, was struck at the beginning of the First Session of the Sixty-Second General Assembly. -

TRANSCRIPT HUNTINGTON DIARIES 1956 Louisbourg, NS. Jan

TRANSCRIPT HUNTINGTON DIARIES 1956 Louisbourg, NS. Jan 1, 1956 Memorandum from 1956: Citizens, and former citizens of the town of Louisbourg, who died during the year 1956 at Louisbourg or elsewhere: Malcolm Henry MacDonald. Jan. 1. Louisbourg, N.S. Mrs. Malcolm Boyd. Jan 4. Sydney, N.S. Mrs. Judson Cross. Jan 14. Sydney, N.S. John H. Skinner. Jan 24. Louisbourg, N.S. John H. Thomas. Feb 9. Sydney, N.S. Daniel Fiandis Jr. March 8. Glare Bay, N.S. Edward Eldon Tanner. March 9. Sydney, N.S. Wisley Tanner. April 3. Louisbourg, N.S. Moses J. Ballah. April 14. Guelph, Ontario. John Dillon. During the past winter . Vancouver, B.C. Charles Phillips. May 11. Glace Bay, N.S. Charles Willot. May 24. Sydney, N.S. Enoch Townsend. May 24. Louisbourg, N.S. Mrs. Harold MacQueen. Aug 25. Louisbourg, N.S. Rev. John G. Hockin. Oct 26. Truro, N.S. Abram Wiley Stacey. Oct 28. Louisbourg, N.S. Robert Beaton Oct 28. Windsor, Ontario. Mrs. Jeremiah Smith. Nov 8. Louisbourg, N.S. Clifton Townsend. Nov 20. Louisbourg, N.S. James Hunt. Dec 13. Sydney, N.S. Mrs. [Rev] John G. Hockin. Dec. Truro, N.S. Louis H. Cann. Dec 17. Inverness, C.B. N.S. No diary entry for Sunday January 1, 1956. January 1956 Monday 2 Lousibourg, N.S. Variable cloudiness with a few light snow flurries. Light to fresh northwest wind. Min temperature, 6, max temperature 17. General Holiday Bank, Post office and all other public offices closed in celebration of New Year’s Day, as well as all the larger shops. -

EDA Registration Status

Status of Electoral Districts Associations This webpage contains the registration status of electoral district associations (EDA) for all registered political parties, as of January 14, 2021. EDAs that have not registered The table below (based on the electoral districts as defined in the 2019 House of Assembly Act) lists, by electoral district and by party, the EDA registration status. Party: • Atlantica: Atlantica Party Association of Nova Scotia (No registered EDAs) • Green: Green Party of Nova Scotia • Liberal: Nova Scotia Liberal Party • NDP: Nova Scotia New Democratic Party • PC: The Progressive Conservative Association of Nova Scotia Status: • “Registered” indicates that the appropriate financial report and EDA registration form has been filed (Form 4 or Form 4-1) and accepted. • Grey (blank) indicates that the appropriate EDA registration form has not been filed and accepted. • “Suspended” indicates that an EDA has not filed their financial reports for the previous calendar year. Electoral District Green Liberal NDP PC 1 Annapolis Registered Registered Registered 2 Antigonish Registered Registered Registered 3 Argyle Registered Registered Registered 4 Bedford Basin Registered Registered Registered 5 Bedford South Registered Registered Registered 6 Cape Breton-Whitney Pier Registered Registered 7 Cape Breton East Registered Registered 8 Chester-St. Margaret's Registered Registered Registered 9 Clare Registered Registered Registered 10 Clayton Park West Registered Registered Registered 11 Colchester-Musquodoboit Valley Registered -

![The First Annual St. Andrews Symposium ] New Brunswick Identity and Culture Summary Report 12-14 August 2007](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4082/the-first-annual-st-andrews-symposium-new-brunswick-identity-and-culture-summary-report-12-14-august-2007-2174082.webp)

The First Annual St. Andrews Symposium ] New Brunswick Identity and Culture Summary Report 12-14 August 2007

2007 University of New Brunswick Supported by the J. William Andrews Fund [ The First Annual St. Andrews Symposium ] New Brunswick Identity and Culture Summary Report 12-14 August 2007 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 J. William Andrews, BA ‗52............................................................................................... 8 Lieutenant-Governor‘s Keynote Address ......................................................................... 10 Discussion ..................................................................................................................... 16 Session 1: Opening Remarks by John McLaughlin, President, University of New Brunswick Topic for Discussion - What Makes Anglophone New Brunswick Special? To Whom Does It Matter?...................................................................................................... 18 Discussion ..................................................................................................................... 20 Talking Stick Discussion .............................................................................................. 21 Open Discussion ........................................................................................................... 23 Session 2: Opening Remarks by Margaret Conrad, O.C. ................................................. 25 Topic for Discussion—Who Are We Now? Who Do We Want to Be? ........................... 25 -

Volume 17 Number 2 Spring-Summer 1992 Volume 17 Numero 2

Volume 17 Number 2 Volume 17 Numero 2 Spring-Summer 1992 Printemps-ete 1992 Volume 17, No. 2 — Spring-Summer/Printemps-ete 1992 FOUNDING EDITOR/REDACTRICE FONDATRICE Donna E. Smyth Acadia University PAST EDITORS/REDACTRICES PRECEDENTES Susan Clark, Brock University Margaret Conrad, Acadia University EDITOR/REDACTRICE EN CHEF Deborah C. Poff Mount Saint Vincent University POETRY EDITOR/DlRECTRICE DE LA POESIE Margaret Harry Saint Mary's University GUEST ARTIST/ARTISTE INVITEE Dianne Pearce Montreal, Quebec MANAGING EDITOR/REDACTEUR GERANT Maurice Michaud Institute for the Study of Women EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS/ASSISTANT-E-S A LA REDACTION PROOFREADING/LECTURE D'EPREUVES Lindsey Arnold, Institute for the Study of Women Paul LeBlanc, Fredericton, New Brunswick Susan Marsh, Institute for the Study of Women Andrea Lamont Mclntyre, Institute for the Study of Women Sophie Pilipczuk, Halifax, Nova Scotia TRANSLATION/TRADUCTION Bradley Horncastle Fredericton, New Brunswick DISCIPLINARY EDITORS/REDACTRICES SPECIALISEES FEMINIST THERAPY: WOMEN AND EDUCATION: Toni Laidlaw, Dalhousie University Lorri Neilsen, Mount Saint Vincent FEMMES ET CINEMA: University Josette Delias, Mount Saint Vincent WOMEN AND ETHNICITY: University Sheva Medjuck, Mount Saint Vincent FEMMES, SCIENCE ET MATHEMATIQUES: University Roberta Mura, Universite Laval WOMEN AND HISTORY: MASCULINITY AND GENDER: Linda Kealey, Memorial University of Blye Frank, Mount Saint Vincent University Newfoundland SOCIALISM AND FEMINISM: WOMEN AND THE LAW: Pat Connelly, Saint Mary's University Sheilah Martin, University of Calgary WOMEN AND AGING: WOMEN AND LITERATURE: Anne Martin Matthews, University of Guelph Lorelei Cederstrom, Brandon University WOMEN AND CANADIAN STUDIES: WOMEN AND PSYCHOLOGY: Jill Vickers, Carleton University Beth Percival, University of Prince Edward WOMEN AND COMMUNICATIONS: Island Thelma McCormack, York University WOMEN AND RACIAL DIVERSITY: WOMEN AND DEMOGRAPHY: Vanaja Dhruvarajan, University of Winnipeg Susan McDaniel, University of Alberta WOMEN AND^ RELIGION: Naomi R. -

Riding by Riding-Breakdown

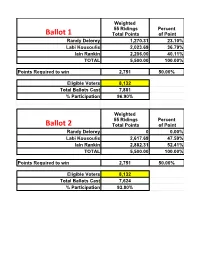

Weighted 55 Ridings Percent Total Points of Point Randy Delorey 1,270.31 23.10% Labi Kousoulis 2,023.69 36.79% Iain Rankin 2,206.00 40.11% TOTAL 5,500.00 100.00% Points Required to win 2,751 50.00% Eligible Voters 8,132 Total Ballots Cast 7,881 % Participation 96.90% Weighted 55 Ridings Percent Total Points of Point Randy Delorey 0 0.00% Labi Kousoulis 2,617.69 47.59% Iain Rankin 2,882.31 52.41% TOTAL 5,500.00 100.00% Points Required to win 2,751 50.00% Eligible Voters 8,132 Total Ballots Cast 7,624 % Participation 93.80% DISTRICT Candidate Final Votes Points 01 - ANNAPOLIS Randy DELOREY 31 26.5 01 - ANNAPOLIS Labi KOUSOULIS 34 29.06 01 - ANNAPOLIS Iain RANKIN 52 44.44 01 - ANNAPOLIS Total 117 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 02 - ANTIGONISH Randy DELOREY 176 53.01 02 - ANTIGONISH Labi KOUSOULIS 35 10.54 02 - ANTIGONISH Iain RANKIN 121 36.45 02 - ANTIGONISH Total 332 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 03 - ARGYLE Randy DELOREY 37 41.11 03 - ARGYLE Labi KOUSOULIS 24 26.67 03 - ARGYLE Iain RANKIN 29 32.22 03 - ARGYLE Total 90 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Randy DELOREY 92 34.72 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Labi KOUSOULIS 100 37.74 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Iain RANKIN 73 27.55 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Total 265 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Randy DELOREY 116 39.59 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Labi KOUSOULIS 108 36.86 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Iain RANKIN 69 23.55 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Total 293 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Randy DELOREY 11 12.36 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Labi KOUSOULIS 30 33.71 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Iain RANKIN 48 53.93 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Total 89 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Randy DELOREY 22 19.47 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Labi KOUSOULIS 32 28.32 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Iain RANKIN 59 52.21 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Total 113 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 08 - CHESTER - St. -

ATLANTIC OCEAN Gulf of Saint Lawrence 2012 PROVINCIAL

47.1° N 59.2° W Point Aconi Cape Dauphin Alder µ 50 10 Point 30 43 Middle Sackville Windsor Florence Junction Bras d'Or New Waterford 44 Sydney Mines Lingan Waverley Lower Sackville North Preston 18 38 50 Glace Bay Lake Echo North 29 Portobello 04 Sydney Gulf of Gardiner Mines Hammonds Plains Bedford 05 Preston South Bar 23 Saint Lawrence 17 16 Donkin Burnside Reserve Mines Mineville Marconi Towers Upper 49 Lawrencetown Whitney Pier 09 21 Grand Lake Road Dartmouth 13 Cole Harbour Leitches Creek 28 Westmount Timberlea Port Morien 19 Balls Creek 45 22 Birch Grove Sydney 26 Halifax Beechville 24 07 27 12 Cow Bay Sydney River Mira Road Eastern Passage 47 46 Homeville Fergusons See CBRM Inset 25 Cove µ Howie Centre Dutch Brook Hatchet Lake Hornes Road 32 1:150,000 1:140,000 49 HRM Inset CBRM Inset Northumberland Strait 46 14 06 39 15 11 41 02 40 48 20 Bay of Fundy 33 30 10 34 35 31 50 21 29 18 01 07 47 See HRM Inset 36 25 37 08 2012 Nova Scotia Electoral Districts 01 Annapolis 27 Halifax Citadel-Sable Island 02 Antigonish 28 Halifax Needham ATLANTIC OCEAN 03 Argyle-Barrington 29 Hammonds Plains-Lucasville 04 Bedford 30 Hants East 05 Cape Breton Centre 31 Hants West 06 Cape Breton-Richmond 32 Inverness 42 07 Chester-St. Margaret's 33 Kings North 08 Clare-Digby 34 Kings South 09 Clayton Park West 35 Kings West 51 10 Colchester-Musquodoboit Valley 36 Lunenburg 27 11 Colchester North 37 Lunenburg West Sable Island 12 Cole Harbour-Eastern Passage 38 Northside-Westmount 03 13 Cole Harbour-Portland Valley 39 Pictou Centre 14 Cumberland North 40 Pictou -

Personal Services Contracts, Based on Data Extracted from SAP on November 25, 2015

List of current Personal Services Contracts, based on data extracted from SAP on November 25, 2015 Approximate Employee Business Area Position Name Annualized Salary Ms Alyson Pierik Agriculture EA to Minister - Agriculture$ 69,573.92 Mr Stephen Moore Communications Nova Scotia Director, Communications$ 91,669.24 Ms Jalana Lewis Communities, Culture& Heritage Knowledge Lead $ 74,849.32 Ms Nancy Radcliffe Communities, Culture& Heritage EA to Minister - CCH/African NS Affairs$ 69,573.92 Mr Terry Dixon Communities, Culture& Heritage Operations Lead $ 74,008.22 Ms Shalyn Jones Communities, Culture& Heritage Health Support Lead $ 74,849.32 Ms Rhonda Atwell Communities, Culture& Heritage Facilitation Lead $ 74,849.32 Ms Lisa Bugden Communities, Culture& Heritage Director $ 135,644.08 Ms Nancy Baroni Community Services Project Director $ 79,999.92 Mr Aaron MacMullin Community Services EA to Minister - Community Services$ 69,573.66 Ms Joy Graham Educ & Early Childhood Develop EA to Minister-Educ. & Early Child.Dev$ 69,573.92 Ms Jessika-Jane Gilker Energy Legal Researcher $ 39,163.28 Mr Joshua Bragg Energy EA to Minister-Energy/Off of Acadian Aff$ 69,573.66 Mr Allan Billard Environment EA to Minister - Environment$ 69,573.92 Ms Courtney Bragg Executive Council Ex. Sect. to Chief of Staff$ 56,866.94 Ms Cleo Alexander Executive Council Administrative Assistant$ 45,768.32 Ms Lana M McGlinchey Executive Council Administrative Assistant$ 40,180.92 Mr Jason Kontak Executive Council Aboriginal Aff. & Comm Relations Officer$ 69,573.92 Ms Laurel Munroe