Oliver Cromwell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Being a Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

The tJni'ers1ty of Sheffield Depaz'tient of Uistory YORKSRIRB POLITICS, 1658 - 1688 being a ThesIs submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by CIthJUL IARGARRT KKI August, 1990 For my parents N One of my greater refreshments is to reflect our friendship. "* * Sir Henry Goodricke to Sir Sohn Reresby, n.d., Kxbr. 1/99. COff TENTS Ackn owl edgements I Summary ii Abbreviations iii p Introduction 1 Chapter One : Richard Cromwell, Breakdown and the 21 Restoration of Monarchy: September 1658 - May 1660 Chapter Two : Towards Settlement: 1660 - 1667 63 Chapter Three Loyalty and Opposition: 1668 - 1678 119 Chapter Four : Crisis and Re-adjustment: 1679 - 1685 191 Chapter Five : James II and Breakdown: 1685 - 1688 301 Conclusion 382 Appendix: Yorkshire )fembers of the Coir,ons 393 1679-1681 lotes 396 Bibliography 469 -i- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research for this thesis was supported by a grant from the Department of Education and Science. I am grateful to the University of Sheffield, particularly the History Department, for the use of their facilities during my time as a post-graduate student there. Professor Anthony Fletcher has been constantly encouraging and supportive, as well as a great friend, since I began the research under his supervision. I am indebted to him for continuing to supervise my work even after he left Sheffield to take a Chair at Durham University. Following Anthony's departure from Sheffield, Professor Patrick Collinson and Dr Mark Greengrass kindly became my surrogate supervisors. Members of Sheffield History Department's Early Modern Seminar Group were a source of encouragement in the early days of my research. -

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1St Half of Each Term HISTORY MTP Y4 Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Su

HISTORY MEDIUM TERM PLAN (MTP) YEAR 4 2020: Taught 1st half of each term HISTORY Autumn 1: 8 WEEKS Spring 1: 6 WEEKS Summer 1: 6 WEEKS MTP Y4 Topic Title: Anglo-Saxons / Scots Topic Title: Vikings Topic Title: UK Parliament Taken from the Year Key knowledge: Key knowledge: Key knowledge: group • Roman withdrawal from Britain in CE • Viking raids and the resistance of Alfred the Great and • Establishment of the parliament - division of the curriculum 410 and the fall of the western Roman Athelstan. Houses of Lords and Commons. map Empire. • Edward the Confessor and his death in 1066 - prelude to • Scots invasions from Ireland to north the Battle of Hastings. Key Skills: Britain (now Scotland). • Anglo-Saxons invasions, settlements and Key Skills: kingdoms; place names and village life • Choose reliable sources of information to find out culture and Christianity (eg. Canterbury, about the past. Iona, and Lindisfarne) • Choose reliable sources of information to find out about • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, the past. backed up by evidence. • Give own reasons why changes may have occurred, • Describe similarities and differences between people, Key Skills: backed up by evidence. events and artefacts. • Describe similarities and differences between people, • Describe how historical events affect/influence life • Choose reliable sources of information events and artefacts. today. to find out about the past. • Describe how historical events affect/influence life today. Chronological understanding • Give own reasons why changes may Chronological understanding • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE have occurred, backed up by evidence. • Understand that a timeline can be divided into BCE and and CE. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

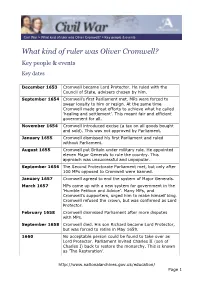

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Oliver Cromwell, Memory and the Dislocations of Ireland Sarah

CHAPTER EIGHT ‘THE ODIOUS DEMON FROM ACROSS THE sea’. OLIVER CROMWELL, MEMORY AND THE DISLOCATIONS OF IRELAND Sarah Covington As with any country subject to colonisation, partition, and dispossession, Ireland harbours a long social memory containing many villains, though none so overwhelmingly enduring—indeed, so historically overriding—as Oliver Cromwell. Invading the country in 1649 with his New Model Army in order to reassert control over an ongoing Catholic rebellion-turned roy- alist threat, Cromwell was in charge when thousands were killed during the storming of the towns of Drogheda and Wexford, before he proceeded on to a sometimes-brutal campaign in which the rest of the country was eventually subdued, despite considerable resistance in the next few years. Though Cromwell would himself depart Ireland after forty weeks, turn- ing command over to his lieutenant Henry Ireton in the spring of 1650, the fruits of his efforts in Ireland resulted in famine, plague, the violence of continued guerrilla war, ethnic cleansing, and deportation; hundreds of thousands died from the war and its aftermath, and all would be affected by a settlement that would, in the words of one recent historian, bring about ‘the most epic and monumental transformation of Irish life, prop- erty, and landscape that the island had ever known’.1 Though Cromwell’s invasion generated a significant amount of interna- tional press and attention at the time,2 scholars have argued that Cromwell as an embodiment of English violence and perfidy is a relatively recent phenomenon in Irish historical memory, having emerged only as the result of nineteenth-century nationalist (or unionist) movements which 1 William J. -

Why Did Britain Become a Republic? > New Government

Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Why did Britain become a republic? Case study 2: New government Even today many people are not aware that Britain was ever a republic. After Charles I was put to death in 1649, a monarch no longer led the country. Instead people dreamed up ideas and made plans for a different form of government. Find out more from these documents about what happened next. Report on the An account of the Poem on the arrest of setting up of the new situation in Levellers, 1649 Commonwealth England, 1649 Portrait & symbols of Cromwell at the The setting up of Cromwell & the Battle of the Instrument Commonwealth Worcester, 1651 of Government http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/ Page 1 Civil War > Why did Britain become a republic? > New government Case study 2: New government - Source 1 A report on the arrest of some Levellers, 29 March 1649 (Catalogue ref: SP 25/62, pp.134-5) What is this source? This is a report from a committee of MPs to Parliament. It explains their actions against the leaders of the Levellers. One of the men they arrested was John Lilburne, a key figure in the Leveller movement. What’s the background to this source? Before the war of the 1640s it was difficult and dangerous to come up with new ideas and try to publish them. However, during the Civil War censorship was not strongly enforced. Many political groups emerged with new ideas at this time. One of the most radical (extreme) groups was the Levellers. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663)

Ezra’s Archives | 35 A Rhetorical Convergence: Rump Ballads and Official Propaganda (1660-1663) Benjamin Cohen In October 1917, following the defeat of King Charles I in the English Civil War (1642-1649) and his execution, a series of republican regimes ruled England. In 1653 Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate regime overthrew the Rump Parliament and governed England until his death in 1659. Cromwell’s regime proved fairly stable during its six year existence despite his ruling largely through the powerful New Model Army. However, the Protectorate’s rapid collapse after Cromwell’s death revealed its limited durability. England experienced a period of prolonged political instability between the collapse of the Protectorate and the restoration of monarchy. Fears of political and social anarchy ultimately brought about the restoration of monarchy under Charles I’s son and heir, Charles II in May 1660. The turmoil began when the Rump Parliament (previously ascendant in 1649-1653) seized power from Oliver Cromwell’s ineffectual son and successor, Richard, in spring 1659. England’s politically powerful army toppled the regime in October, before the Rump returned to power in December 1659. Ultimately, the Rump was once again deposed at the hands of General George Monck in February 1660, beginning a chain of events leading to the Restoration.1 In the following months Monck pragmatically maneuvered England toward a restoration and a political 1 The Rump Parliament refers to the Parliament whose membership was composed of those Parliamentarians that remained following the expulsion of members unwilling to vote in favor of executing Charles I and establishing a commonwealth (republic) in 1649. -

Parish of Kirkby Malghdale*

2 44 HISTORY OF CRAVEX. PARISH OF KIRKBY MALGHDALE* [HIS parish, at the time of the Domesday Survey, consisted of the townships or manors of Malgum (now Malham), Chirchebi, Oterburne, Airtone, Scotorp, and Caltun. Of these Malgum alone was of the original fee of W. de Perci; the rest were included in the Terra Rogeri Pictaviensis. Malgum was sur veyed, together with Swindene, Helgefelt, and Conningstone, making in all xn| car. and Chircheby n car. under Giggleswick, of which it was a member. The rest are given as follows :— 55 In Otreburne Gamelbar . in car ad glct. 55 In Airtone . Arnebrand . mi . car ad glct. 55 In Scotorp Archil 7 Orm . in . car ad glct. •ii T "i 55 In Caltun . Gospal 7 Glumer . mi . car ad giet. Erneis habuit. [fj m . e in castell Rog.f This last observation applies to Calton alone. The castellate of Roger, I have already proved to be that of Clitheroe; Calton, therefore, in the reign of the Conqueror, was a member of the honour of Clitheroe. But as Roger of Poitou, soon after this time, alienated all his possessions in Craven (with one or two trifling exceptions) to the Percies, the whole parish, from the time of that alienation to the present, has constituted part of the Percy fee, now belonging to his Grace the Duke of Devonshire. \ [* The parish of Kirkby: in-Malham-Dale, as it is now called, contains the townships of Kirkby-Malham, Otterburn, Airton, Scosthrop, Calton, Hanlith, Malham Moor, and Malham. The area, according to the Ordnance Survey, is -3,777 a- i r- 3- P- In '871 the population of the parish was found to be 930 persons, living in 183 houses.] [f Manor.—In Otreburne (Otterburn) Gamelbar had three carucates to be taxed. -

Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Governor John Blackwell: His Life in England and Ireland OHN BLACKWELL is best known to American readers as an early governor of Pennsylvania, the most recent account of his J governorship having been published in this Magazine in 1950. Little, however, has been written about his services to the Common- wealth government, first as one of Oliver Cromwell's trusted cavalry officers and, subsequently, as his Treasurer at War, a position of considerable importance and responsibility.1 John Blackwell was born in 1624,2 the eldest son of John Black- well, Sr., who exercised considerable influence on his son's upbringing and activities. John Blackwell, Sr., Grocer to King Charles I, was a wealthy London merchant who lived in the City and had a country house at Mortlake, on the outskirts of London.3 In 1640, when the 1 Nicholas B. Wainwright, "Governor John Blackwell," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (PMHB), LXXIV (1950), 457-472.I am indebted to Professor Wallace Notestein for advice and suggestions. 2 John Blackwell, Jr., was born Mar. 8, 1624. Miscellanea Heraldica et Genealogica, New Series, I (London, 1874), 177. 3 John Blackwell, Sr., was born at Watford, Herts., Aug. 25, 1594. He married his first wife Juliana (Gillian) in 1621; she died in 1640, and was buried at St. Thomas the Apostle, London, having borne him ten children. On Mar. 9, 1642, he married Martha Smithsby, by whom he had eight children. Ibid.y 177-178. For Blackwell arms, see J. Foster, ed., Grantees 121 122, W. -

Oliver Cromwell and the Regicides

OLIVER CROMWELL AND THE REGICIDES By Dr Patrick Little The revengers’ tragedy known as the Restoration can be seen as a drama in four acts. The first, third and fourth acts were in the form of executions of those held responsible for the ‘regicide’ – the killing of King Charles I on 30 January 1649. Through October 1660 ten regicides were hanged, drawn and quartered, including Charles I’s prosecutor, John Cooke, republicans such as Thomas Scot, and religious radicals such as Thomas Harrison. In April 1662 three more regicides, recently kidnapped in the Low Countries, were also dragged to Tower Hill: John Okey, Miles Corbett and John Barkstead. And in June 1662 parliament finally got its way when the arch-republican (but not strictly a regicide, as he refused to be involved in the trial of the king) Sir Henry Vane the younger was also executed. In this paper I shall consider the careers of three of these regicides, one each from these three sets of executions: Thomas Harrison, John Okey and Sir Henry Vane. What united these men was not their political views – as we shall see, they differed greatly in that respect – but their close association with the concept of the ‘Good Old Cause’ and their close friendship with the most controversial regicide of them all: Oliver Cromwell. The Good Old Cause was a rallying cry rather than a political theory, embodying the idea that the civil wars and the revolution were in pursuit of religious and civil liberty, and that they had been sanctioned – and victory obtained – by God.