Issue Framing and Identity Politics in the Log Cabin Republicans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Border War Intel Find out What Wyo

You’re paying student government $35.92 per semester. Did they serve you this week? | Page 5 PAGE 6 Border War Intel Find out what Wyo. thinks of this year’s battle for the Bronze Boot THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado Volume 121 | No. 62 ursday, November 1, 2012 COLLEGIAN www.collegian.com THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 the STRIP Halloween Heroes CLUB With the predicted end of the world nearly upon us (12/21/12), it is time to start focusing our attention on ways in which the world will end. is week: the technologi- cal apocalypse of the Robot Uprising (already in progress). Ways in Which Robots will Rule the World LEFT: Haruto Yoshikawa chases his big brother while donning his Superman halloween costume on the west lawn Wednesday evening. Yoshikawa is a refreshing reminder of why homeowners give out candy to young kids and not college students. (Photo by Hunter Thompson) RIGHT: A lone shark looks on as a group of Atheists and Christians duke it out on the plaza this Wednesday. As the two groups shout out declaring their opinion is right, the shark believes that both groups look tasty. (Photo by Kevin Johansen) Cars We already rely “Most of my friends are party a liated and will vote for the ticket rather than vote on robots when it comes to car for the candidate and I just think that’s studpid.” manufacturing. Chris Lopina | senior journalism major ey assemble chassis and weld various parts together. Soon, cars Meet the Undecided themselves will not only Some students still unsure of vote choice with less than a week remaining be capable of self-navigation, By KATE WINKLE cording to Davis. -

Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts

SHAW.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 11/15/2017 3:32 AM Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts Katherine Shaw* Abstract The President’s words play a unique role in American public life. No other figure speaks with the reach, range, or authority of the President. The President speaks to the entire population, about the full range of domestic and international issues we collectively confront, and on behalf of the country to the rest of the world. Speech is also a key tool of presidential governance: For at least a century, Presidents have used the bully pulpit to augment their existing constitutional and statutory authorities. But what sort of impact, if any, should presidential speech have in court, if that speech is plausibly related to the subject matter of a pending case? Curiously, neither judges nor scholars have grappled with that question in any sustained way, though citations to presidential speech appear with some frequency in judicial opinions. Some of the time, these citations are no more than passing references. Other times, presidential statements play a significant role in judicial assessments of the meaning, lawfulness, or constitutionality of either legislation or executive action. This Article is the first systematic examination of presidential speech in the courts. Drawing on a number of cases in both the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts, I first identify the primary modes of judicial reliance on presidential speech. I next ask what light the law of evidence, principles of deference, and internal executive branch dynamics can shed on judicial treatment of presidential speech. -

View Full Issue As

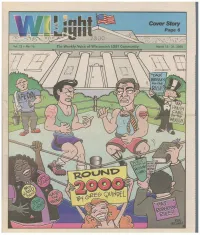

Cover Story Page 6 ,-; - ">>(C Vol. 13 • No. 16 The Weekly Voice of Wisconsin's LGBT Community March 15 - 21, 2000 // \\\ f /%7 C HEALTH CARE • forfhe to 4 AP. NVKE WHALE&AY R oot417 • %at I 25,1 &czE(7 QuirloEt .40 41 WI LIAM5 A\ www.wngnt.tom VOLUNTEER TODAY And Change Your World Comedienne Suzanne Wegtenhoefet Wanna' Start Saturday, March 25 • 8pm Some Doors Open at 7pm moon Then why not volunteer at I til/44 I I 111011 your local neighborhood LGBT Community Center? 2090 Atwood Ave • Madison • Answer the LCBT info line $17.50 Advance / $19.50 Door • Start a program • Help raise funds with special guest • Expand our library. • Support youth leadership ZRZYA tit* Milwaukee Smooth as silk, Dublin, Ireland - V V V based world-jazz funksters . v V V I,GBT - Time Out (London) Commtutity Center BUY YOUR TICKETS AT: The Barrymore Box Office Exclusive Company (State & High Point) 170 South 2nd. Street Magic Mill • A Room of One's Own "Wickedly righteous . 414-271-2656 Star Liquor • Green Earth www.mkelght.org a riotous look at life." OR CHARGE BY PHONE: (608) 241-8633 - San Diego Gay & Lesbian Times Make Them BODY INSPIRED With Envy MILWAUKEE'S EAST SIDE HEALTH CLUB TANNING & MASSAGE 272.8622 2009 E. Kenilworth Place (2 blocks south of North Ave.) www.wilight.com News &Politics March 15 - 21, 2000 Wight 3 and sentence, however, because of over- employment matters. whelming evidence that Burdine's defense All 28 Republican Senators voted to nullify National lawyer slept through much of the trial. -

Proquest Dissertations

Forging a Gay Mainstream Negotiating Gay Cinema in the American Hegemony Peter Knegt A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August, 2008 ©Peter Knegt, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45467-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-45467-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

1 Chairman Reince Priebus C/O Republican National Committee

Chairman Reince Priebus C/O Republican National Committee 310 First Street, SE Washington, DC 20003 April 8, 2013 Dear Chairman Priebus, We write to express our great displeasure with the RNC commissioned report titled Growth and Opportunity Project. As individuals and organizations which represent millions of grassroots, faith-based voters who have supported (politically and financially) thousands of Republican candidates who share our values, we write to say: The Republican Party makes a huge historical mistake if it intends to dismantle this coalition by marginalizing social conservatives and avoiding the issues which attract and energize them by the millions. Unfortunately, the report dismisses the Reagan Coalition as a political relic of the past. It’s important to remember that from 1932-1980, the Republican Party was a permanent minority party. Political debate was confined to economic issues like the expansion of the Federal Government, taxes, and national security. It was not until 1980 with key changes in the GOP Platform and the nomination of Ronald Reagan that social conservatives were clearly invited to be an important addition to this coalition. Millions of “Reagan Democrats” voted not only for President Ronald Reagan, but became active in supporting other GOP candidates who shared their faith-based family values. That’s how Republicans achieved many successes since 1980 at every level of government. The report states on page seven that “America looks different.” It certainly does, but here are some facts about minority outreach…not opinions and theories from DC Consultants: 1 1. In 2004, President Bush carried Ohio because of the outreach to African-American pastors supporting a traditional marriage amendment on the ballot. -

Romney Takes on Trump After Super Tuesday, Sanders' Supporters Go

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/usappblog/2016/03/04/romney-takes-on-trump-after-super-tuesday-sanders-supporters-go-after-warren-and-job- growth-continues-us-national-blog-roundup-for-27-february-4-march/ Romney takes on Trump after Super Tuesday, Sanders’ supporters go after Warren, and job growth continues: US national blog roundup for 27 February – 4 March USAPP Managing Editor, Chris Gilson looks at the best in political blogging from around the Beltway. Jump to The 2016 campaign Super Tuesday The Democratic Candidates The Republican Candidates The 11th GOP debate The Obama Administration The Beltway and the Supreme Court Foreign policy, defense and trade Obamacare and health policy The economy and society The 2016 Campaign Welcome back to USAPP’s regular round up of commentary from US political blogs from the past week. The big news this week was Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton’s Super Tuesday victories, bringing them one step closer to the respective Republican and Democratic presidential nominations. We’ll get in to more detail on the Super Tuesday results in a minute, but first, we take a look at commentary on the campaign in general. On Monday – ahead of Super Tuesday – FiveThirtyEight says that if we want to understand what’s ‘roiling’ the 2016 election, then we should pay Oklahoma a visit, given the populist enthusiasm of many of its voters. Credit: DonkeyHotey (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0) For many, a Trump/Clinton showdown for the general election now seems to be inevitable. Political Animal gives some early thoughts on how such a race might run, writing that Clinton will be more than happy to go after Trump hard, unlike his GOP primary challengers. -

Governor Decision-Making: Expansion of Medicaid Under the Affordable Care Act

Governor Decision-making: Expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act By Robin Flagg A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Health Services and Policy Analysis in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ann C. Keller, Chair Professor William H. Dow Professor John Ellwood Professor Paul Pierson Fall 2014 Governor Decision-making: Expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act Copyright 2014 By Robin Flagg Abstract Governor Decision-making: Expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act By Robin Flagg Doctor of Philosophy in Health Services and Policy Analysis University of California, Berkeley Professor Ann C. Keller, Chair This is a study of factors that influence gubernatorial decision making. In particular, I ask why some governors decided to expand Medicaid under the Accountable Care Act (ACA) while others opted against it. Governors, like all chief executives, are subject to cross-pressures that make their jobs challenging. Budgetary pressures may differ from personal ideology and administrative infrastructures may not allow for decisive moves. Add to the equation political pressures – in particular the pressure to align with partisan positions – and a governor is faced with a myriad of opposing and interrelated factors, each requiring attention, when taking a particular position. The calculation required of a governor when deciding upon a salient issue is thus extremely complicated and nuanced. Although interesting in its own right, governor decision making is of additional significance because it may shed light on how the effects of increasing party strength and polarization are playing out at the state level. -

View Entire Issue As

& LAcfrossE/MADisoN (6og) MnwAURE "i4i NORTm=RN wlscoNslN (7i5) #aaurk:Zi4i|;!e#7S8t6o #€}%=e?6%g,7Sgu#So^7V.e Ballgame 196S2nd Milwaukee (414)273-7474 afty84Z.?£35T`n Sti La Crosse 546oi Boom 625South2ndst Rainbo`^/'s End 417 Jay Street, La Crosse M"waukee (414)277-5040 +#*rfurs5Applegatecourt Boot camp 209 E National Milwaukee (414)643-6900 i:yopit!Tg#if36i#W.GrandAve. C'est La Vie 231 S 2nd Milwaukee (414)291-9600 EL+#t#')'2i5f$3Ej5VAshlngton EL#iawl3(`fu§).z85rge.#82SL %:#iLff4hit|'„t8t,t..WriFowardAve Emeralds 801 E Hadley St, ELEL#+6b`872¥5"B9St.. Milwaukee (414) 265-7325 i:3°€f#re4t(`7f§|'8%e#;tr6eet. :'iugjd*|he2Y:tMiRE)ukee(414)643-5843 Wolfe's Den 302 E. Madlson Eau Claire (715ys32-9237 The Harbor Room 117 E. GTeenfield Aye. JT's Bar and Grill 1506 N. 3rd Milwaukee (414)672-7988 Superior (715)-394-2580 The Maln 1217 Tower Ave Fat:¥n¥j,#ibJaaruE:tc(5:4f3u8T.n8t3!:unge Superior, WI (715)392-1756 &Eui2iu°Y7#;3#°.32S2t5WWW.totheoz.com y2¥NCW:t#'fiiisw#RX+i:4)347-1962 Moma's 1407 S. First St Milw (414)643ro377 ELffiJRR¥R##3v3iELELs3% Nut Hut 1500 W Scott ffiEj:ills,Pwi|!i€i%Y.iR8# Mlwaukee (414)647-2673 SWITCH 124 W National NormAsrmN wlscoNslN col Milwaukee (414)220-4340 Crossroads 1042 W. Wisconsin Ave. The fazzbah Bar a Grille 171Z W pierce St. Appleton (920)830-1927 Milwaukee(414)672-8466 w\^r\^r.tazzbali.com Rascals Bar a Gr" 702 E. Wls., Appleton (920)954-9262 This ls It 418 E Wells, Milw (414)278-9192 Brandyis 11 1126 Main, Green Bay 020H37-3917 Triangle 135 E National, Milwaukee (414)383-9412 G#+#y`(;:af#;#r, Walkert pint 818 S 2nd st (414)643-7468 SASS 840 S. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JULY 27, 2011 No. 114 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was other fees that pay for the aviation weather. We need that system. Well, if called to order by the Speaker pro tem- system. It is partially funded by the this impasse continues, we will not pore (Mr. MARCHANT). users of that system with ticket taxes have that system by next winter. f and such. That is $200 million a week. Now, who is that helping? Who are Now, what’s happened since? Well, you guys helping over there with these DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO three airlines, three honest airlines— stupid stunts you’re pulling here? $200 TEMPORE Frontier Airlines, Alaska, and Virgin million a week that the government The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- America—lowered ticket prices be- isn’t collecting that would pay for fore the House the following commu- cause the government isn’t collecting these critical projects, put tens of nication from the Speaker: the taxes. But the other airlines, not so thousands of people to work, and now WASHINGTON, DC, much. They actually raised their tick- it’s a windfall to a bunch of airlines. July 27, 2011. et prices to match the taxes, and But don’t worry, the Air Transport I hereby appoint the Honorable KENNY they’re collecting the windfall. Association says, these short-term in- MARCHANT to act as Speaker pro tempore on At the same time, their association, creases, that is by the airlines increas- this day. -

Election 2016: Looking Ahead to a Trump Administration

Election 2016: Looking Ahead to a Trump Administration November 17, 2016 2016 Election Results • Trump carried swing states (FL, IA, OH) as well as states that have traditionally voted blue in presidential races (PA, WI) • Michigan has 16 electoral votes, which will most likely go to Trump for 306 total • Popular Vote (as of 11/16/16): Clinton 47.6% / Trump 46.7%* *Source: USElectionAtlas.org Source: New York Times 2 “A Country Divided by Counties” • County results show Trump’s decisive gains were in rural areas in the rust belt/greater Appalachia 3 2016 Senate Results • Republican-Majority Senate • 48 Democrats / 51 Republicans • 1 seat yet to be called • Pence can vote on ties • Democrats gained 2 seats Source: New York Times, updated Nov. 14, 2016 4 2018 Senate Map • 33 Senate seats are up • 25 Democratically-held seats are up • Competitive seats: • North Dakota (Heidi Heitkamp) • Ohio (Sherrod Brown) • Wisconsin (Tammy Baldwin) • Indiana (Joe Donnelly) • Florida (Bill Nelson) • Missouri (Claire McCaskill) • Montana (Jon Tester) • New Jersey (Bob Menendez) • West Virginia (Joe Manchin) • Filibuster? Nuclear Option? 5 2016 House Results • Republican-Majority House • The Republican Party currently controls the House, with 246 seats, 28 more than the 218 needed for control • Final Results pending (4 seats yet to be called) • Democrats pick up ~7-8 seats Source: New York Times, updated Nov. 14, 2016 6 Trump’s Likely Cabinet Choices • White House Chief of Staff: Reince Priebus, the Chairman of the Republican National Committee • Strategic -

Thevanderbilt Political Review

TheVanderbilt Political Review F I I N HE I E E S I L L NG T P C Spring 2011 TheVanderbilt VPR | Spring 2011 Political Review Table of Contents Spring 2011 • Volume 4 • Issue 2 President Matthew David Taylor 3 Interview with Dr. William Turner Vice Presidents Allegra Noonan Interview conducted by Britt Johnson Nathan Rothschild and Sid Sapru Editor-in-Chief Libby Marden 4 Alumni Perspective: Assistant Editor-in-Chief Sid Sapru A Conversation with President George W. Bush Online Director Noah Fram Wyatt Smith Events Director Leia Andrew Zaid Choudhry College of Arts & Science and Secretary Hannah Jarmolowski Peabody College Treasurer Ryan Higgins Class of 2010 Public Relations Melissa O’Neill 6 The Red Sea Art Director Eric Lyons Nick Vance Director of Layout Melissa McKittrick College of Arts & Science Community Outreach Nick Vance Class of 2014 Print Editors Eliza Horn 7 The Unfinished Revolution: Egypt’s Transition to Vann Bentley Civilian Rule Nathan Rothschild Sloane Speakman Christina Rogers College of Arts & Science Hannah Rogers Class of 2012 Andrea Clabough Emily Morgenstern 9 A Hopeful Pakistan, A Hopeful America Nicholas Vance Sanah Ladhani College of Arts & Science Online Writers Megan Covington Class of 2012 Mark Cherry 10 Wrapped in the Flag and Carrying a Cross Adam Osiason Eric Lyons John Foshee Jillian Hughes College of Arts & Science Jeff Jay Class of 2014 12 The Libyan No Fly-Zone: A New Paradigm for Events Staff Michal Durkiewicz Humanitarian Intervention and Reinforcing Democracy Jennifer Miao Atif Choudhury Caitlin Rooney College of Arts & Science Kenneth Colonel Alex Smalanskas-Torres Class of 2011 13 Who Failed Our Country’s Children? Faculty Adviser Mark Dalhouse Zach Blume College of Arts & Science Class of 2014 Vanderbilt‘s first and only multi-partisan academic journal 14 Exorcising the Boogeyman featuring essays pertaining to political, social, and economic events that are taking place in our world as we speak. -

The Most Popular President? - the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies - Grand Va

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Features Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies 2-15-2005 The oM st Popular President? Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/features Recommended Citation "The osM t Popular President?" (2005). Features. Paper 115. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/features/115 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Features by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Most Popular President? - The Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies - Grand Va... Page 1 of 5 The Most Popular President? Abraham Lincoln on Bookshelves and the Web This weekend we celebrated the birthday of Abraham Lincoln -- perhaps the most popular subject among scholars, students, and enthusiasts of the presidency. In bookstores Lincoln has no rival. Not even FDR can compare -- in the past two years 15 books have been published about Lincoln to FDR's 10, which is amazing since that span included the 60th anniversaries of D-Day and Roosevelt's historic 4th term, and anticipated the anniversary of his death in office. Lincoln is also quite popular on the web, with sites devoted to the new Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, his birthplace, home, and papers. And he is popular in the press -- perhaps no deceased former president is more frequently incorporated into our daily news. Below, the Hauenstein Center has gathered recently written and forthcoming books about Lincoln, links to websites, and news and commentary written about Lincoln since the New Year.