The Cryptic Caper Bush

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zovs-Tustin-Bistro__

TUSTIN BISTRO MEZZE PLATE choice of… any two 10.95 any three 12.95 any four 14.95 any five 16.95 hummus • babaganoush • lebni • tabouleh • walnut caviar red pepper feta dip • stuffed grape leaves • armenian string cheese & marinated olives STARTERS SAUTEED CALAMARI 14.95 garlic, shallots, lemon, fresh herbs, chardonnay butter sauce, crostini GARLIC SHRIMP 15.95 extra virgin olive oil, fresh herbs, chili flakes, teardrop tomatoes, grilled crostini DIRTY FRIES 10.95 fresh herbs, parmesan cream, cabernet mushroom gravy ROASTED BEETS 11.95 crimson and golden beets, creamed goat cheese, candied walnuts, red wine vinaigrette BRUSSELS AND BACON 11.95 flash fried brussel sprouts, nueske bacon, caper vinaigrette, pinot noir syrup TAHINI TACOS roasted pepper aioli, fresh salsa, tahini sauce, mini greens, corn tortillas, cabbage spiced chicken 13.95 • marinated lamb 15.95 GREENS ZOV’S SIGNATURE MIXED GREEN 10.95 cucumber, tomato, feta, chives, herb vinaigrette MEDITERRANEAN CHOP CHOP 15.95 chicken, cucumber, tomato, egg, feta, herbs, garbanzo, red onion, pita, pinot noir syrup, caper vinaigrette MOROCCAN SPICED SALMON 18.95 m’jadarah, organic greens, tomato, feta, aged balsamic dressing SHRIMP GREEK 19.95 mixed greens, cucumber, tomato, kalamata olives, red onion, feta, pita croutons, lemon mint dressing HERB CRUSTED CHICKEN PAILLARD 17.95 parmesan herb crusted chicken, greens, walnuts, goat cheese, tomato, red onion, balsamic vinaigrette SEARED AHI CEASAR 17.95 zahtar crust, hearts of romaine, croutons, parmesan, olives, roasted red peppers, garlic -

Common Name Scientific Name Class Toxicity 2020 PEND OREILLE

2020 PEND OREILLE COUNTY NOXIOUS WEED LIST I. Designated mandantory control noxious weeds currently found growing in Pend Oreille County: Common Name Scientific Name Class Toxicity BIGHEAD KNAPWEED Centaurea macrocephala A N CLARY SAGE Salvia sclarea A N FLOWERING RUSH Butomus umbellatus A N VOCHIN KNAPWEED Centaurea nigrescens A N ANNUAL BUGLOSS Anchusa arvensis B-designate N BLACK KNAPWEED Centaurea nigra B-designate N BUTTERFLY BUSH Buddleja davidii B-designate N COMMON BUGLOSS Anchusa officianalis B-designate N COMMON REED Phragmites australis B-designate N EURASIAN WATERMILFOIL Myriophyllum spicatum B-designate in lakes N KNOTWEEDS, giant, Japanese & Polygonum sachalinense, P. cuspidatum B-designate N Bohemian & P. x bohemicum B-designate N HERB ROBERT Geranium robertianum B-designate N KOCHIA Bassia scoparia B-designate Y - Nitrate concentrator LEAFY SPURGE Euphorbia virgata B-designate Y - dermal LOOSESTRIFE, garden Lysimachia vulgaris B-designate N LOOSESTRIFE, purple & wand Lythrum salicaria, L. virgatum B-designate N MEADOW KNAPWEED Centaurea moncktonii B-designate N MUSK THISTLE Carduus nutans B-designate N MYRTLE SPURGE Euphorbia myrsinities B-designate Y - dermal PERENNIAL PEPPERWEED Lepidium latifolium B-designate N PLUMELESS THISTLE Carduus acanthoides B-designate N POLICEMAN’S HELMET Impatiens glandulifera B-designate N RUSH SKELETONWEED Chondrilla juncea B-designate N SALTCEDAR Tamarix ramossisma B-designate N SCOTCH BROOM Cytisus scoparius B-designate N SCOTCH THISTLE Onopordum acanthium B-designate N SPURGE LAUREL Daphne laureola B-designate N TANSY RAGWORT Senecio jacobaea B-designate Y - destroys liver VIPER'S BUGLOSS Echium vulgare B-designate N YELLOW STARTHISTLE Centaurea solstitialis B-designate Y - to horses BABYSBREATH Gypsophila paniculata C N BUFFALOBUR Solanum rostratum C Y - cattle, sheep & horses COMMON CATSEAR Hypochaeris radicata C Y - to horses ENGLISH IVY (4 cultivars) Hedera helix, H. -

Efficient Protocol for the in Vitro Plantlet Production of Caper

agronomy Article Efficient Protocol for the In Vitro Plantlet Production of Caper (Capparis orientalis Veill.) from the East Adriatic Coast Snježana Kereša 1,*, Davor Stankovi´c 2, Kristina Batelja Lodeta 3 , Ivanka Habuš Jerˇci´c 1, Snježana Bolari´c 1, Marijana Bari´c 1 and Anita Bošnjak Mihovilovi´c 1 1 Department of Plant Breeding, Genetics and Biometrics, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Svetošimunska cesta 25, Zagreb 10000, Croatia; [email protected] (I.H.J.); [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.B.M.) 2 Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Svetošimunska cesta 25, Zagreb 10000, Croatia; [email protected] 3 Department of Pomology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Svetošimunska cesta 25, Zagreb 10000, Croatia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +385-1239-3801 Received: 8 May 2019; Accepted: 9 June 2019; Published: 11 June 2019 Abstract: Caper (Capparis orientalis Veill.) is a species rich in bioactive compounds, with positive effects on human health. It has a great adaptability to harsh environments and an exceptional ability to extract water from dry soils. In Croatia, the caper grows as a wild plant, and its cultivation is insignificant, which is probably due to propagation difficulties. Micropropagation could be a solution for this. The aim of this study was to investigate the success of the micropropagation, in vitro rooting, and acclimatization of Capparis orientalis Veill. Shoot proliferation was tested in a Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium, with sucrose or glucose, and in 13 treatments, presenting the combined effect of different cytokinins and their concentrations. -

Four-Year Study on the Bio-Agronomic Response of Biotypes of Capparis Spinosa L

agriculture Article Four-Year Study on the Bio-Agronomic Response of Biotypes of Capparis spinosa L. on the Island of Linosa (Italy) Salvatore La Bella 1,†, Francesco Rossini 2,† , Mario Licata 1, Giuseppe Virga 3,*, Roberto Ruggeri 2,* , Nicolò Iacuzzi 1 , Claudio Leto 1,2 and Teresa Tuttolomondo 1 1 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences, Università degli Studi di Palermo, Viale delle Scienze 13, Building 4, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] (S.L.B.); [email protected] (M.L.); [email protected] (N.I.); [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (T.T.) 2 Department of Agricultural and Forest Sciences, Università degli Studi della Tuscia, 01100 Viterbo, Italy; [email protected] 3 Research Consortium for the Development of Innovative Agro-Environmental Systems (Corissia), Via della Libertà 203, 90143 Palermo, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.V.); [email protected] (R.R.) † These authors are equally contributed. Abstract: The caper plant is widespread in Sicily (Italy) both wild in natural habitats and as special- ized crops, showing considerable morphological variation. However, although contributing to a thriving market, innovation in caper cropping is low. The aim of the study was to evaluate agronomic and production behavior of some biotypes of Capparis spinosa L. subsp. rupestris, identified on the Island of Linosa (Italy) for growing purposes. Two years and seven biotypes of the species were tested in a randomized complete block design. The main morphological and production parame- Citation: La Bella, S.; Rossini, F.; ters were determined. Phenological stages were also observed. -

Capparis Cynophallophora1

Fact Sheet FPS-104 October, 1999 Capparis cynophallophora1 Edward F. Gilman2 Introduction This 6- to 20-foot-tall, native shrub is an upright to spreading plant that is related to plant producing edible capers (Fig. 1). The evergreen leaves of the Jamaica Caper are light- green above, with fine brown scales below. These glossy, oval leaves are folded together when they first emerge and give the plant’s new growth a bronze appearance. The leaves also have a notched tip. Twigs are brownish gray and pubescent. Jamaica Caper flowers have very showy, two-inch-long, purple stamens and white anthers and white petals. The inflorescence is comprised of terminal clusters consisting of 3 to 10 individual flowers. The fruits are 3- to 8-inch-long cylindrical pods containing small brown seeds that are embedded in a scarlet pulp. General Information Scientific name: Capparis cynophallophora Pronunciation: KAP-ar-riss sin-oh-fal-oh-FOR-uh Common name(s): Jamaican Caper Family: Capparidaceae Figure 1. Jamaican Caper. Plant type: tree USDA hardiness zones: 10 through 11 (Fig. 2) Availablity: generally available in many areas within its Planting month for zone 10 and 11: year round hardiness range Origin: native to Florida Uses: near a deck or patio; screen; border; attracts butterflies; recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or for Description median strip plantings in the highway; small parking lot islands Height: 6 to 15 feet (< 100 square feet in size); medium-sized parking lot islands Spread: 8 to 12 feet (100-200 square feet in size); large parking lot islands (> 200 Plant habit: vase shape square feet in size) Plant density: dense 1.This document is Fact Sheet FPS-104, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

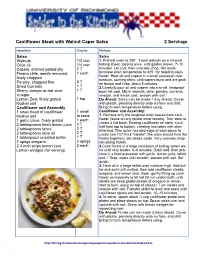

Cauliflower Steak with Walnut Caper Salsa 2 Servings

Cauliflower Steak with Walnut Caper Salsa 2 Servings Ingredients Quantity Methods Salsa Salsa Walnuts 1/3 cup 1. Preheat oven to 350°. Toast walnuts on a rimmed Olive oil 1/4 cup baking sheet, tossing once, until golden brown, 7–10 Capers, drained patted dry 2 T minutes. Let cool, then coarsely chop. Set aside. Fresno chile, seeds removed, 1 each Increase oven temperature to 425° for roasting cauli- flower. Heat oil and capers in a small saucepan over finely chopped medium, swirling often, until capers burst and are gold- Parsley, chopped fine 3 T en brown and crisp, about 5 minutes. Dried Currants 1 T 2.Carefully pour oil and capers into a small heatproof Sherry vinegar or red wine 1 T bowl; let cool. Mix in walnuts, chile, parsley, currants, vinegar vinegar, and lemon zest; season with salt. Lemon Zest, finely grated 1 tsp Do Ahead: Salsa can be made 1 day ahead. Cover Kosher salt with plastic, pressing directly onto surface and chill. Cauliflower and Assembly Bring to room temperature before using. 1 small head of cauliflower 1 small Cauliflower and Assembly: Kosher salt to taste 1. Remove only the toughest outer leaves from cauli- 1 garlic clove, finely grated 1 each flower (leave on any tender inner leaves). Trim stem to 2 tablespoons fresh lemon juice 2 T create a flat base. Resting cauliflower on stem, cut in half from top to bottom, creating two lobes with stem 2 tablespoons tahini 2 T attached. Trim outer rounded edge of each piece to 2 tablespoons olive oil 2 T create two 1½"-thick "steaks" (the stem should hold the 1 tablespoon unsalted butter 1 T florets together); set steaks aside. -

Tomato, Olive, & Caper Pasta

Tomato, Olive, & Caper Pasta with Garlic Bread TIME: 30-40 minutes SERVINGS: 2 This creamy lumaca rigata pasta gets pops of briny flavor from Castelvetrano olives and capers—and pairs perfectly with crunchy garlic bread. MATCH YOUR BLUE APRON WINE Zesty & Tropical Serve a bottle with this symbol for a great pairing. Ingredients KNICK KNACKS: 6 oz 1 14-oz can 2 cloves 1/4 cup 1 oz 1/4 cup LUMACA RIGATA WHOLE PEELED GARLIC HEAVY CREAM CASTELVETRANO GRATED PASTA TOMATOES OLIVES PARMESAN CHEESE 1 1 bunch 2 Tbsps 1 Tbsp 1 Tbsp SMALL BAGUETTE KALE BUTTER CAPERS ITALIAN SEASONING* * Whole Dried Basil, Sage, Oregano, Savory, Rosemary, Thyme, & Marjoram Download our iOS or Android app to watch how-to videos, manage your account, and track your deliveries. 1 1 Prepare the ingredients: F Preheat the oven to 450°F. F Heat a large pot of salted water to boiling on high. F Wash and dry the fresh produce. F Halve the baguette. F Peel and finely chop the garlic. F Remove and discard the stems of the kale; roughly chop the leaves. F Place the tomatoes in a bowl; gently break apart with your hands. F Using the flat side of your knife, smash the olives; remove and discard the pits, then roughly chop. 2 Cook the pasta: F Add the pasta to the pot of boiling water and cook 9 to 11 minutes, or 2 3 until al dente (still slightly firm to the bite). Turn off the heat. F Reserving 1/2 cup of the pasta cooking water, drain thoroughly and return to the pot. -

Product List Flavonoids Botanica Gmbh • Industrie Nord • 5643 Sins • Switzerland • • +41 41 757 00 00

Product list flavonoids Botanica GmbH • Industrie Nord • 5643 Sins • Switzerland • www.botanica.ch • +41 41 757 00 00 Basic structure of flavonoids The following list contains extracts in glycerine/water, with flavonoids. Flavonoids also include 1 anthocyanins (natural colours) and are members of the polyphenol group (secondary plant sub- stances). Flavonoids are widespread in the plant kingdom and therefore also occur in foodstuffs. Among other qualities they possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. A number of flavonoid-rich plants are also used in medicine. Flavonoids are predominantly water soluble and therefore undetectable in oil soluble carrier materials. The products listed below are not stand- ardised products with guaranteed minimum flavonoid content. The following products can be used for cosmetic and technical purposes. Botanica neither performs nor commissions tests on animals. Our raw materials are natural and can vary slightly from harvest to harvest without affecting the quality of the product. Further in- formation can be found in the corresponding specification. Please note that some products are not available all year round. Please ask us about the availabil- ity. This list is not exhaustive and represents only a part of our products. If you are looking for specific products for your formulation, we are looking forward to your contact. Product list flavonoids Botanica GmbH • Industrie Nord • 5643 Sins • Switzerland • www.botanica.ch • +41 41 757 00 00 Various references were used for the following flavonoid -

Lemon-Caper Tilapia Blueapron.Com with Orzo, Zucchini & Peppers

Lemon-Caper Tilapia blueapron.com with Orzo, Zucchini & Peppers 4 SERVINGS | 30–40 MINS ST Y E & Serve with Blue Apron IF YOU CHOSE A CUSTOMIZED OPTION, visit the Current tab in the Blue Apron app or Z wine that has this symbol T R L at blueapron.com for ingredients (denoted with an icon) and instructions tailored to you.* A O P I C blueapron.com/wine Ingredients 4 Skin-On Salmon 1/2 lb Orzo Pasta 4 Tilapia Fillets Fillets If you customized this recipe, your SmartPoints may differ from what’s above. 2 Red, Yellow, or 2 Zucchini 2 cloves Garlic Orange Bell Peppers Scan this barcode in your WW app to track SmartPoints (the barcode at left provides 1 Lemon 1 bunch Parsley 1 Tbsp Capers the standard recipe and the barcode at right provides the customized version). Wine is not included in SmartPoints as packaged. Skip adding salt during prep 2 Tbsps Crème and cooking, and see nutrition info for 1 oz Butter 1 Tbsp Verjus Blanc sodium as packaged. Choose nonstick Fraîche cooking spray (0 SmartPoints) instead of olive oil (1 SmartPoint per teaspoon) to coat your pan before heating. 1 Tbsp Weeknight To learn more about WW and SmartPoints visit ww.com. The 1 WW logo, SmartPoints and myWW are the trademarks of WW Hero Spice Blend International, Inc. and are used under license by Blue Apron, LLC. 1. Onion Powder, Garlic Powder, Smoked Paprika & Whole Dried Parsley *Ingredients may be replaced and quantities may vary. Learn more at blueapron.com/pages/wellness Hey, Chef! Try these WW pro-tips: Skip adding salt during prep and cooking, and see nutrition info for sodium as packaged. -

The Houseboat Grill - Tonight’S Dinner Menu

THE HOUSEBOAT GRILL - TONIGHT’S DINNER MENU BEGINNINGS Hearty Beef & Black Bean Chili Soup, Sour Cream…..965 Garlic Caesar Salad, Chili Garlic Croutons…..1245 Add Grilled Boneless Chicken Breast…..1775 Add 5 Grilled Shrimp…..2395 Grilled Calamari, Tomato Concassé, Capers, Nut Brown Butter…..1575 Spicy Peel & Eat Pepper Shrimp, Scotch Bonnet Beurre Blanc…..1525 BBQ Braised Beef Rib Soft Taco – Smoked Paprika Garlic Crema, Pickled Carrots, Flour Tortilla…..1395 House Cured Gravlax, Whole Grain Mustard Dill Sauce, Swedish Knäckebröd…..1750 Taramosalata – Greek Fish Roe Dip – Cod Roe, Lemon Juice, Extra Virgin Olive Oil, Pita Bread…..1350 Grilled Garlic Shrimp, Kalamata Olive, Tomato & Garlic mayonnaise…..1595 Peanut & Panko Crusted Lobster Cake, Tamarind Chili Mayonnaise…..1885 Char-grilled Octopus, Garlic, Extra Virgin Olive Oil and Scallion…..1725 MAINS Lemon Caper Pipe Rigate Pasta, Garlic, Toasted Almonds, Grilled Local Market Vegetables, Parmesan Cheese …..1945 Sautéed Chicken Cutlets, Chardonnay Dijon Mustard Cream Sauce, Scallion Mashed Potatoes, Bacon & Onion Fried Cabbage…..2725 Grilled Chicken Breast, Lemon Caper Pipe Rigate Pasta, Garlic, Toasted Almonds, Sweet Green Peas, Parmesan Cheese …..2395 Baked Snapper Fillet with Almond Panko Crust, Roasted Red Pepper Cream, Parmesan Risotto Cake, Dijon Vinaigrette Vegetable Slaw…..2995 Grilled Norwegian Salmon Fillet with Scallion & Ginger, Warm Lemon Miso Vinaigrette, Wild Rice Pilaf, Stir Fried Cabbage & Carrots…..4350 Sautéed Lemon Pepper Garlic Shrimp, Brandied Sauce Homard, Classic -

Garlic-Caper Chicken Blueapron.Com with Fettuccine & Zucchini

Garlic-Caper Chicken blueapron.com with Fettuccine & Zucchini 2 SERVINGS | 20–30 MINS US H L & P Serve with Blue Apron Ingredients wine that has this symbol F R Y blueapron.com/wine 2 Boneless, Skinless 1/2 lb Fettuccine U I T 1 Zucchini Chicken Breasts Pasta 2 cloves Garlic 1 Tbsp Capers 2 Tbsps Butter 2 Tbsps Crème 1/4 cup Grated 1 Tbsp Italian Fraîche Parmesan Cheese Seasoning1 1. Whole Dried Basil, Sage, Oregano, Savory, Rosemary, Thyme & Marjoram 1 Prepare the ingredients 4 Cook the zucchini • Fill a large pot 3/4 of the way up • In the pan of reserved fond, heat with salted water; cover and heat 2 teaspoons of olive oil on to boiling on high. medium-high until hot. • Wash and dry the zucchini; halve • Add the sliced zucchini, lengthwise, then thinly slice Italian seasoning, and half the crosswise. chopped garlic; season with • Peel and roughly chop 2 cloves salt and pepper. Cook, stirring of garlic. occasionally, 3 to 4 minutes, or until lightly browned. • Roughly chop the capers. • Transfer to a bowl. • Wipe out the pan. 2 Cook the chicken • Pat the chicken dry with paper towels; season with salt and 5 Make the garlic-caper topping pepper on both sides. • In the same pan, heat 2 • In a medium pan (nonstick, if teaspoons of olive oil on you have one), heat 2 teaspoons medium-high until hot. of olive oil on medium-high • Add the chopped capers and until hot. remaining chopped garlic; • Add the seasoned chicken. Cook season with salt and pepper. -

Food in Ancient Egypt

oi.uchicago.edu FEB 2 6 1987 J j:J. RECTOR'S LIBRARY OINN ews& .JRlENT AL INSTITUTE 108 otes i,.;, IVERSIri O~ CH Cfo..G Issued confidentially to members and friends No. 108 March-April, 1987 Not for publication FOOD IN ANCIENT EGYPT The civilization of ancient Egypt left behind mummies, in tricate works of art, and immense monuments of architecture, all of which survived millennia. Reliefs from these monuments often depict the preparation and propagation of food, as well as its consumption. The conventional agricultural scenes pictured in tomb after tomb, as well as the hunting and fishing scenes, all attest to the importance of feeding the household. The reliefs and paintings in the tombs give us a great deal of information about the food and the ways in which it was raised, prepared, and served in ancient Egypt, although no written recipes for food preparation have been discovered. Tomb illustrations show men standing over a spit roasting a joint of meat, fish, or fowl. The women are depicted preparing bread and beer. Small clay ovens, on top of which pots could be placed for simmering, were used to bake the bread. Metal braziers have been found that presumably were used for pre tured themselves as slender, elegant people. Very few draw paring meat, fowl, or fish . ings depict obese people and when they do, it is an indication Fuel consisted of either reeds, charcoal, or animal dung. of age and material success. Olives for olive oil were originally imported, but in the late The wealthy seemed particularly fond of a fine bread, proba 18th Dynasty their cultivation was introduced into Egypt.